Interviews

Have You Ever Been So Angry That You Burst Into Flames?

Kevin Wilson on figuring out how to take care of each other when we’re all so damaged

Unconditional love often comes with a side effect of incessant fear. What happens if the object of affection is hurt? How can you cope with losing someone who was once your whole life? A parent or guardian’s unconditional love for a child goes even further. The fear is even deeper, denser. Almost flammable.

Kevin Wilson depicts this fear in an alarmingly unique way in his novel Nothing to See Here, through characters who spontaneously combust and come out the other side unscathed. It’s one thing to worry about the natural disasters that could befall a toddler, but the parents and caretakers in this story have to deal with the seemingly supernatural as well. Wilson writes a world populated by dynamic characters and paranormal events, begging questions about how far they will go to protect their loved ones.

I spoke with Kevin Wilson about the vulnerability of parenting, his childhood obsession, and figuring out how to take care of each other when we’re all so damaged.

Frances Yackel: Where did the idea for spontaneously combusting children come from?

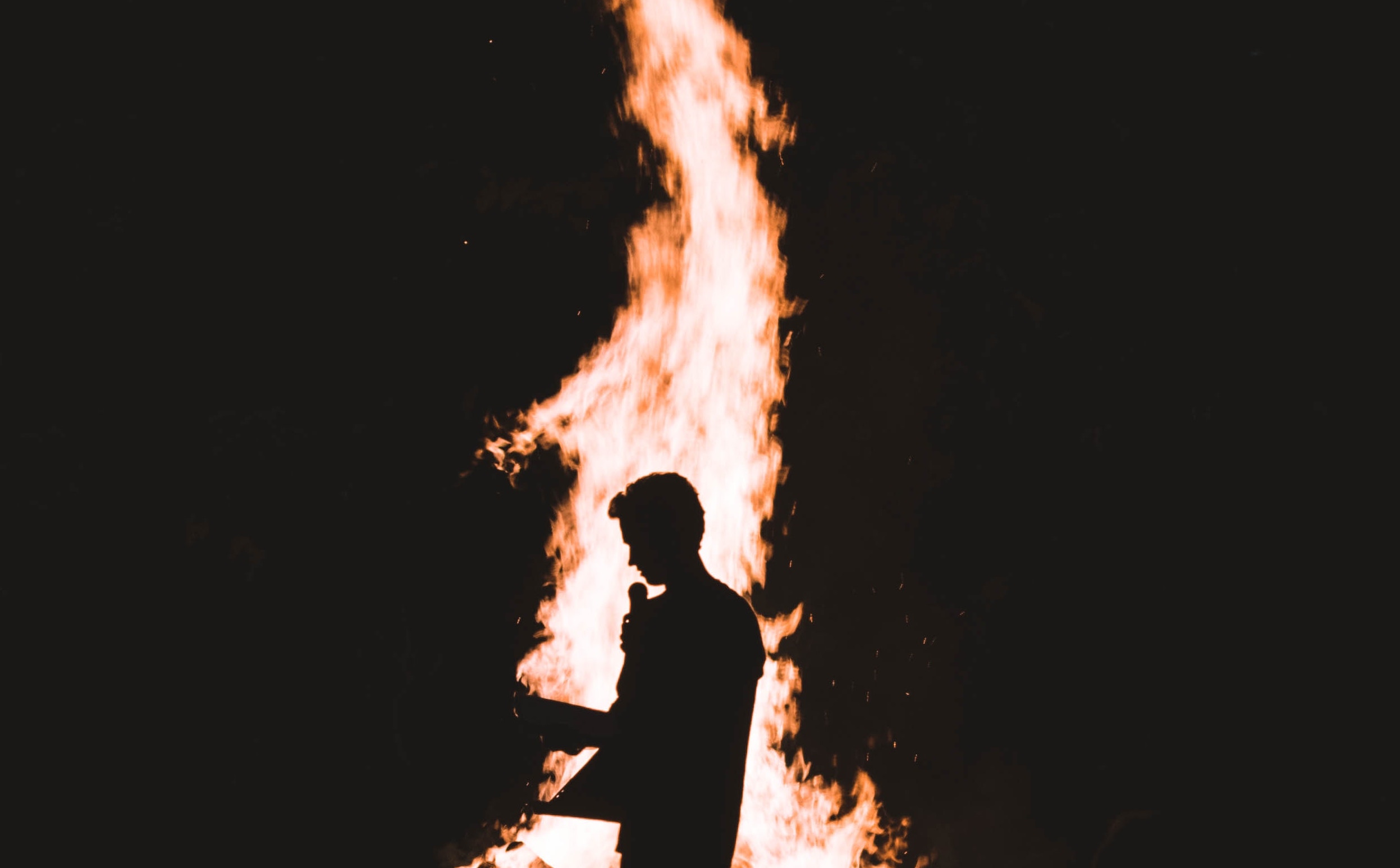

Kevin Wilson: It came from the same place that most of my writing comes from, which is childhood obsession. I was maybe ten when I first heard about spontaneous human combustion and it became this immediate and powerful obsession, something that I couldn’t get rid of. And so I had this recurring image in my head of people bursting into flames.

I was ten when I heard about spontaneous human combustion and it became this immediate and powerful obsession.

And this is actually the third time I’ve published a book that has spontaneous human combustion in it, so obviously I’m still processing it. For so much of my life, it was inward, thinking about myself blowing up, worrying about that possibility or kind of wanting it to happen just to relieve the anxiety that filled me up.

But once I had kids, and became responsible for them, and felt that love for them while also realizing how difficult it was to take care of them, that obsession kind of naturally shifted to them, imagining what it would be like to take care of someone who might burst into flames. I think that’s been a big shift in my work, moving from looking at the world through the perspective of a kid, the freshness of each experience, and now trying to look at the world from the perspective of an adult, realizing how different it is, how every action is tinged with a kind of nostalgia that connects you to the person you used to be.

FY: The doctor in the novel takes some guesses at certain diseases or reasons that a person might spontaneously combust, was there a research process to this? If so, what were some of the things you found?

KW: I don’t think it’s laziness, though it might very well be, but I try to do as little research as possible if it ultimately doesn’t matter. The doctor in the novel is touched by a kind of mania, so I tried to imagine not what might be scientifically possible, but what a crazy person would think. The holy spirit, a divine possession, something like that made sense to me. In the books I read as a kid, the explanations were kind of boring, a cigarette flame burning the fats in someone’s body if they were passed out. Or internal organs rubbing together to produce a flame.

FY: Lillian fascinates me. She’s direct and unapologetic and knows how to tick people off when she wants to, but she’s so tender toward the people that she empathizes with. She’s biting but she loves deeply. Could you talk about the development of this character, how did you get in her head?

KW: A former student recently told me that she read the novel and imagined Lillian as me in a wig. I don’t know if that’s true, but I do think the way my brain works, my internal monologue, is pretty similar to Lillian. But I had to move beyond myself to imagine her as a separate character and I think that you touch on something about her that interested and surprised me, which is her innate ability to know how to tick people off. And that she kind of likes fucking with people who irritate her, which is not me at all. I tend to hate someone in my mind with an intensity that might psychically damage them, but I can’t confront people. I honestly was thinking about Merricat Blackwood in We Have Always Lived in the Castle, and Ramona Quimby, who was my favorite character as a kid. But unlike Merricat, I didn’t want her to be a psychopath. I wanted that biting nature to be wrapped up with her ability to empathize and love, though it might be an odd way of doing it.

FY: As for the children; all three of them jump off the page. They are each so alive and unique. Does having children of your own influence your characters or the narrative?

KW: Oh, for sure. Not just my own kids, but observing their friends, watching all their strange little personalities, how wonderful they are. They have such odd mannerisms and it’s all kind of alive and shifting because they don’t really know yet how to control or hide anything. In creating the novel, I didn’t want to put too much weight on the kids. I didn’t want them to be oracles or adults in kids’ bodies. I wanted them to be what they are, children, in all the weird ways that childhood functions. And that’s what’s lovely about children, that moment when they gain clarity and see something, the way the world opens up. I love watching that with my kids.

FY: Lillian is seemingly always looking for what it means to really care for another human being. In almost every chapter, she has a different answer to the question. As a social animal, humans are brought up against this question every day. We need to look out for one another in order to coexist safely. In what ways do you think the addition of a scientific anomaly, such as spontaneously combusting children, change the way we might look at that question?

I’m trying to figure out how we take care of each other when we’re all so damaged in different ways.

KW: I don’t want to be overtly symbolic or anything. To my mind, the book is about taking care of fire children. I want that. But at the heart of it, I’m trying to figure out how we take care of each other when we’re all so damaged in different ways. The fire children are a kind of huge, visible issue that might relate to disability, and I’m trying to figure that out. I believe that we have to take care of each other. That’s the only thing that matters in the world, to help everyone get safely to whatever comes after this life. And that kind of altruism sounds so nice in theory, but people are weird and it’s not that easy all the time. How do we protect ourselves and other vulnerable people when it isn’t easy? How do we respect every person and take their unique elements into consideration? And as Lillian tries to figure it out, I’m trying to do the same thing. And I’m not there yet, but I’m trying.

FY: The reality of children setting themselves on fire (and coming out unscathed) is maybe difficult to fathom happening in this world. But the side effects are certainly tangible. The children get upset, or angry, or stressed, and the adults around them become stunned, or hysterical. But some adults, Lillian in particular, stay calm and can help others calm down. This story has made me think about how I react to other people’s emotions—children as well as adults. Because emotions are so difficult to convey, it can sometimes be difficult to know how to respond in a respectful and safe way. Could you talk about this theme in your novel? How does the spontaneous combustion bring out the best, or worst, in us?

KW: I think Jasper and Madison, in some ways, because they have come from privilege, are stunned by the need and vulnerability of these children. And I think about this a lot, how sometimes people with the most power, with the most ability to affect change in the world, seem repulsed by vulnerability, that simply engaging with it might rub off on them and they’ll lose that power. They’d rather put up a huge wall between themselves and that need. But I think Lillian, because of her own history, has a better sense of how to deal with the children, to actually treat them as human beings. And to do that, I think you have to make yourself vulnerable, to be willing to accept the pain that comes with being vulnerable, in order to help someone else.

And that’s really fucking hard for me to do, because my own brain is so overwhelmed most of the time, because I live in a state of anxiety, but it’s what I focus most of my energy on, especially with my kids and my students and the people in my life that I love. I try to allow myself to be vulnerable in ways that lets me connect and try to move forward together with that person. So we’re each helping the other one get somewhere better than when we started. I think that’s what Lillian and Bessie and Roland are doing for each other.