interviews

Here’s a Pill to Sleep the Year Away

Ottessa Moshfegh throws scatological-level shade at our culture’s quest for betterment

You know people don’t eat any more, right? They cure. They juice. They fast. They are pescaterians. Pollotarians. They are flexitarians, but only if they have looked the meat in question in its eyeballs, first.

Deciding what to eat and sourcing it takes a certain class of Americans hours every day. And then they need to spend additional hours working the food off. Enter areo-yoga, paddleboard yoga, yoga for your dog. Skin tautness and follicle integrity are also very important. There’s facial yoga, cold sculpting, dermaplaning, microneedling, prejuvention, injectable nose jobs. We are told by glossy bloggers to wash our hair reverently, and we are told by the same bloggers not to wash our hair at all.

Once you’re looking good and eating right, you have to invest substantial effort into the maintenance of your social life, as well. It is not enough to quietly enjoy the company of your companions any longer, you must broadcast the proof of friendship to the digital rooftops — I am re-taking this selfie with this person because I like them very much!

What a time to be alive, even our procrastination necessitates panache! It takes hard work to think of the tweet that will telegraph our boredom while also making it evident that we are very BUSY. It takes artistry to snap just the right photo to communicate your “mood.”

I am exhausted writing this diatribe, and I’m exhausted living alongside it — the unrelenting march to the place (or follower count) where we’ll be livin’ our best lives. And yet, the world feels so hopeless, the sense of right and wrong so conjoined, that perhaps the only thing that feels controllable is our social media posts and our digestive tracts. Is this how the valid message that self-care is not just permissible, but necessary, mushroomed into an excuse to put self first, self second, and hell, also on third?

Enter into this age of self, a nervy mike-drop of a novel from beloved author Ottessa Moshfegh that throws scatological-level shade at our culture’s quest for betterment. The unnamed heroine of Moshfegh’s latest, My Year of Rest and Relaxation has but one goal: to sleep the year away. To achieve this, she will enrage her best friend Reva by letting her bikini body soften, consume VHS cassettes instead of solids, and enlist a magnificently incompetent psychiatrist, Dr. Tuttle, to play pill pusher to her sleeping beauty for twelve inactive months.

In these times of #silenceiscomplicity when concerned citizens are donating, marching, cold-calling, and campaigning, all the while visibly incorporating these efforts into their larger “brand”, Moshfegh’s profile of a privileged, beautiful white urbanite’s decision to hibernate feels especially provocative, catapulting My Year Of into a new and darker category of guilty pleasure reads.

A committed Moshfegh admirer, I will follow her cutting intelligence and sardonic humor wherever she puts it to work, so I was especially pleased to have the opportunity to speak with her by phone about her delectable fourth book.

Courtney Maum: Kirkus called your latest novel “The finest existential novel not written by a French author.” What do you think, Ottessa? Is My Year Of existential?

Ottessa Moshfegh: That’s pretty apt, I definitely felt like it was existential. I wonder if other people will see it that way? It is a grappling with an existential question of consciousness and being and the trap of being. From the outside, the book is about a pretty woman who has everything but is miserable, who decides to sleep her troubles away. Which I guess in a mundane sense is exactly what she’s doing, but as a writer I think it’s a little more profound than that. What exactly is uncomfortable about this, what are the reasons for human misery? Loss, purposelessness, difficulty with human relationships, alienation from human society, loneliness. The usual. These questions are essential questions that interest me, inherent in everything I write.

CM: I read in The White Review that Newton — your hometown, right? — has the highest number of psychiatrists. Is that true, and if it is true, do you have an idea why that is so?

What are the reasons for human misery? Loss, purposelessness, alienation, loneliness. This essential question is inherent in everything I write.

OM: I don’t know if it’s still true now, but it makes perfect sense. Newtown is a very wealthy suburb of Boston, a hub of education in the northeast. The values in that culture have a lot to do with achievement and a higher echelon of human interest: academia, science, philosophy, art… It isn’t a place that really embraces human nature in its more spiritual component. There’s a lot of pressure. Kids do SAT prep when they are twelve, they’re working on their resumés, their extracurricular shit. Most families in Newtown have two high achieving parents, so how much time do you actually get to spend with your kid when he’s not with the tutor, at a cello lesson…I think the lack of human connection is exactly why people develop mental illness. Psychiatry works perfectly in a culture like Newton’s because it’s a substitute for love and care. It makes me think: what is an education actually getting us? It’s not giving us tools to actually deal with our humanity. It gives us tools to use our brain in ways that allow us to be more productive and make us more alienated with each other.

CM: Your writing is revered by many people, including me, because it’s blunt and dirty and smart and it doesn’t seem to give a fuck, which isn’t to say that it comes off as careless, but that your writing seems to fly in the face of what it means to be a good citizen, a clean person, a useful person, and perhaps even a “good” woman in our culture. What is it like to be in promotion mode for My Year of Rest and Relaxation? You kind of have to be in “good girl” mode to promote books, but you’re sometimes seen as writing “bad girl” literature.

OM: I don’t see it as good girl/bad girl. I’ve given a lot to my work and I want it to have a life outside of my apartment, so I have to share more of myself more than is comfortable with the public and journalists. It can seem degrading when I’m misunderstood or reduced or put in a box, or when my work is used to speak to some kind of political idea that I don’t stand for or feel divorced from, or disinterested in. Sometimes, it’s a negotiation — promotion — but mostly it feels like a job. I try to be honest, and in the course of trying to be honest I might feel like I reveal too much, and I feel invaded, and I need to do what I need to do to regain my sense of privacy. But you know, I’m not like…Jennifer Lawrence. I’m a writer that many people will not read. They’re not going to read whatever I say on the Internet, so the stakes aren’t really that high.

CM: I wasn’t going to get into this, but I feel compelled to. You’re completely off of social media. What’s that like?

OM: I don’t have the energy for self-promotion, I have an amazing publicist for that. Liz Calamari. I completely trust her. Social media for me as a living person is toxic, and it’s exactly the opposite of how I want to live as a writer. The internet in general feels like a very toxic place to me for the past couple of years. I don’t want people to see pictures of me with my nieces or my partners. You have to protect yourself psychically from other people. There are probably a lot of people who don’t like me, and I don’t want to have that juju. You give them an inch and they make a hundred million assumptions. I’m not interested in connecting with people over the Internet. I write books to connect with people. For me, social media is a mind fuck, time suck. If you don’t look at it, you won’t have to think about it.

CM: You said in another interview that you think sports would have been good for you. Why is that? Weirdly, I often think that myself — I feel like I’d be a less selfish person if I’d grown up playing more team sports. But I convinced my high school to consider “the piano” as a sport…

OM: I was a pianist, too. I devoted many hours of each day to practicing — I had two two-hour lessons a week; I was very serious. My mom is a violist, and she felt sports were dangerous because I could hurt my hands. Moving your body is such an essential part of being alive. When I was nine, I got in put in a back brace called the “The Boston Brace.” It was supposed to inhibit the development of my scoliosis. It was very difficult and very, very painful and restricted my movement in a lot of ways. Having to wear that brace for two or three years, I developed chronic back pain. I wish that I grew up with a better relationship to strength and to agility, a better relationship to my body and to flexibility.

CM: You’ve also said that writing “My Year of” made you insane. How so?

It seems really sad that we have to make up ourselves to look like inhuman beings who don’t shit and piss and fart and wake up looking like anime porn stars.

OM: I think there’s a necessary level of insanity when you are writing a novel. I don’t know anyone who can write a novel casually. You know, have a cup of tea and sit and look out the window and type. It was a very difficult book for me. Every project you take on is in a karmic sense exactly what you need. The lessons I learned from this book were very difficult and hard won. I wrote it without a home, I was leaving one place, going from this residency to that residency. It was a difficult time. After finishing it, I knew I needed a year off from writing a novel because I felt like that was really fucking intense. But now I’ve forgotten the treachery and the suffering! I’m excited about a new novel. Like it’s an adventure I’m going to go on and discover all these things.

CM: Let’s talk about the very specific year that this book is sent in. The year 2000 — about what, 9 months before Sept. 11th? Did you try the book out in any other time period first?

OM: If I had written the book in 2018, it wouldn’t have made sense. Some of my stories happen in contemporary culture, but writing about past, it just feels like there is so much more room. The book I’m hoping to write takes place in Victorian San Francisco. I like that distance, the hindsight, the separation between my consciousness and the consciousness of my characters.

When I started the first ten pages, I didn’t know what time it was, but once the story actually began, it was obvious to me. The book had to be set in the age before digital news because it infiltrates everything. You can’t ever be away from it. My narrator needed to be isolated, but also, I was thinking how misinformed we are. I was thinking about 9/11 and in the course of writing the book I was learning things that were really upsetting. We spend all this time tweeting distractions from what is actually the truth, and the truth is extremely horrifying.

CM: Whoopi Goldberg has a pretty big inspirational role to play in this book. Can you talk about her role?

OM: The admiration of Whoopi Goldberg in the book is my admiration for her. She has always stood out as the real person in the fake scene. She is always Whoopi Goldberg. I think she’s a fucking genius. Her karmic role is to break through the fog of delusion and she very rightly chose the medium of on-screen entertainment, which is a machine of delusion, a delusion-making machine. I think she’s been important culturally, and an important figure for me. She’s black, she’s a woman, she’s not a sex symbol. She’s opinionated and totally, totally singular and I grew up watching her movies on VHS in the 80s. She resonates with me. I love her.

CM: All of your characters, perhaps without exception, have pretty sketchy hygiene. What’s your feeling on hygiene, specifically American hygiene?

OM: I take a shower once a day, I wash my hair every day, wash my face 5 times a day, brush my teeth 4–5 times daily, I’m insanely hygienic. I can never feel clean enough. It gives me pleasure to feel clean — the world is so dirty.

I spent a lot of time in my protagonist’s Upper West Side apartment, having her break down her old habits. In the exposition, I get into it: she’s done colonics, highlights, facials and all that shit. All of the money that women are paying through the nose so they look attractive for a man who probably doesn’t brush his teeth in the morning. The discrepancy is so insane. Especially now, women are turning into an ideal of femininity for the patriarchy that looks like an avatar of a woman. The Kardashian thing with the make-up, what’s it called?

CM: Contouring.

OM: Right, contouring. Don’t we have fucking contours in our face? All of that, it’s such a fucking waste of time, and it seems really sad. People are wasting so much time on their vanity which makes them less of a person, what’s the pay-off? What do you actually want? It seems really sad that we have to make up ourselves to look like inhuman beings who don’t shit and piss and fart and wake up looking like anime porn stars. I think it’s really poisoning us. We live in such a pornographic culture, that look has become so mainstream. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to feel beautiful and loved, but the level of artifice seems really ridiculous.

CM: Your main character is considered “beautiful” in that she’s tall, thin, stylish, blond. Was it important to you that she be beautiful in this way?

OM: Making her beautiful was partly a “fuck you” to all the people who came up and asked how I could write a female character as disgusting as Eileen. So I thought, if she was blond and tall and wore fashionable clothing, would you still call her that?

CM: We’ve spoken a little off the record about my own struggles with insomnia. While I was reading your book, I was actually in a bad situation because I was out of sleeping pills and my regular Doc was being sued and couldn’t prescribe any more for me. He was someone who was frankly pretty terrible, someone I found on the Internet, the contemporary equivalent of the Yellow Pages, where your narrator finds her psychiatrist. My doctor was so incredibly incompetent that I actually felt bad for him, so I just kept going, I felt like someone had to. Accordingly, I feel worlds of affection for Dr. Tuttle who is operating in her own passionate world of glorious medical blundering. Can you tell me a little bit about her origin?

OM: How did she come into being? I can’t say too much about it exactly. She seems to embody psychiatry — psychiatry is an evil industry. It saves a lot of people but I think at the heart of it, it is an evil industry. It pathologizes people’s struggles and creates these labels that they can make money off of by selling people drugs. And it’s so fucking dark, the book. There had to be levity. It couldn’t all be dark. Dr. Tuttle was so fun to write. Whenever I would be like, it’s time for me to see Dr. Tuttle! It was like she was waiting for me with some ridiculous new thing. She was the joy.

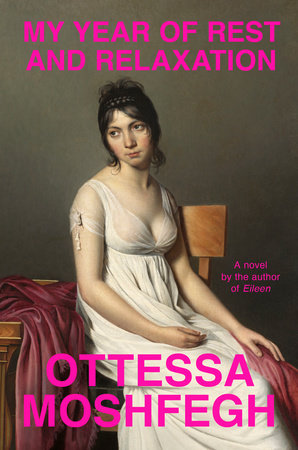

CM: Your cover is spectacular. Were you the genius behind it — did you have any involvement?

OM: I have to say I will take credit for the image and the hot pink font. Working with Penguin Press is always great, it really feels collaborative. The pink type face is important!

CM: Is there anything that you think no one else might ask you about that you would like to add?

OM: I would want to say that by having given an interview about what I think and what I did, that I also hope people that people enjoy the book if they want to, and get what they can out of it. I don’t matter.