Books & Culture

Hollywood and the Postwar American Myth

The Netflix docuseries ‘Five Came Back’ asks, are all war films propaganda?

In covering the rise of film in the early twentieth century and their effect on those growing up alongside it, the historian Robert Sklar wrote, “Are we not all members or offspring of that first rising generation of movie-made children whose critical emotional and cognitive experiences did in fact occur in movie theaters?” Sklar’s question, found in his 1975 book Movie-Made America, echoed a study written by Henry James Forman three decades before, appropriately titled Our Movie Made Children. Halfway through the century, the sense that cinema could influence its avid viewers wasn’t so much an anxiety as an established fact, especially considering its reach: by 1940, sixty million Americans — more than half the adult population of the United States — went to movie theaters each week. It’s no surprise then that with the arrival of World War II, coinciding with the height of Hollywood’s near-monopoly on American leisure time, those working in the Los Angeles backlots were called on to harness their influence in order to serve American interests.

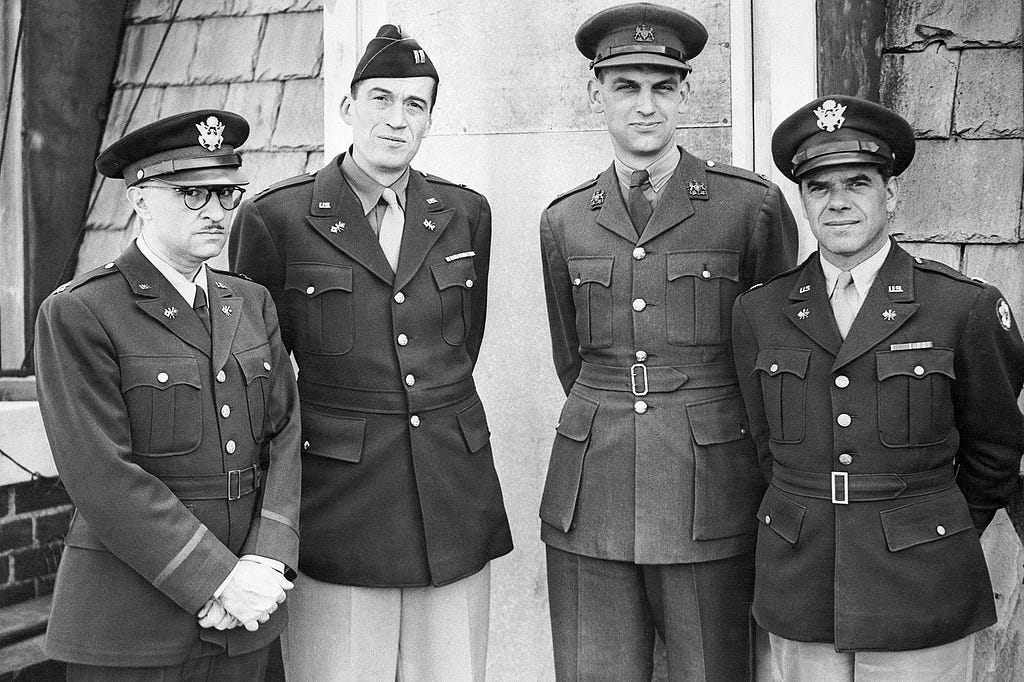

Mark Harris’ book, Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War — now a Netflix docuseries — outlines how five golden-era Hollywood directors (George Stevens, Frank Capra, John Ford, William Wyler, and John Huston) came to play a decisive role in chronicling the war and, more critically, shaping public opinion about the U.S.’s involvement in it. “Filmmakers could not win the war,” Harris writes, “but Capra, Ford, Huston, Stevens, and Wyler had already shown that they could win the people.” As a result, World War II became the first conflict for which average Americans could see moving images of the battlefield in what must have seemed like real time. The newsreels which preceded each screening of that era gave as visceral a look at warfare as Americans had ever experienced.

But, as many of these directors soon learned, the line between filmmaking and propaganda was almost nonexistent. “All film,” including his own, Stevens noted years later, “is propaganda.”

In the Netflix adaptation of Five Came Back, Mexican director Guillermo del Toro describes why he so strongly responds to Frank Capra’s work, admitting that while watching he finds himself ceasing to think — so overwhelmed by the heart-tugging work of films like It’s a Wonderful Life that he cannot help but turn his mind off. This is of course the hallmark of an effective film, but, as Harris’s book and the Netflix series make clear, it comes with an accompanying danger — a danger for instance exemplified in a film like Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 Triumph of the Will.

While the work that Stevens, Capra, Huston, Ford, and Wyler carried out for the War Department doesn’t fit squarely beside Riefenstahl’s Nazi-glorifying, Hitler-commissioned propaganda film, it was also not so comfortably far removed. The clashes which Five Came Back chronicles, between the seasoned Hollywood directors and the War Department, suggests the filmmakers’ awareness that the storytelling talent they brought to their military assignments functioned as a double-edged sword.

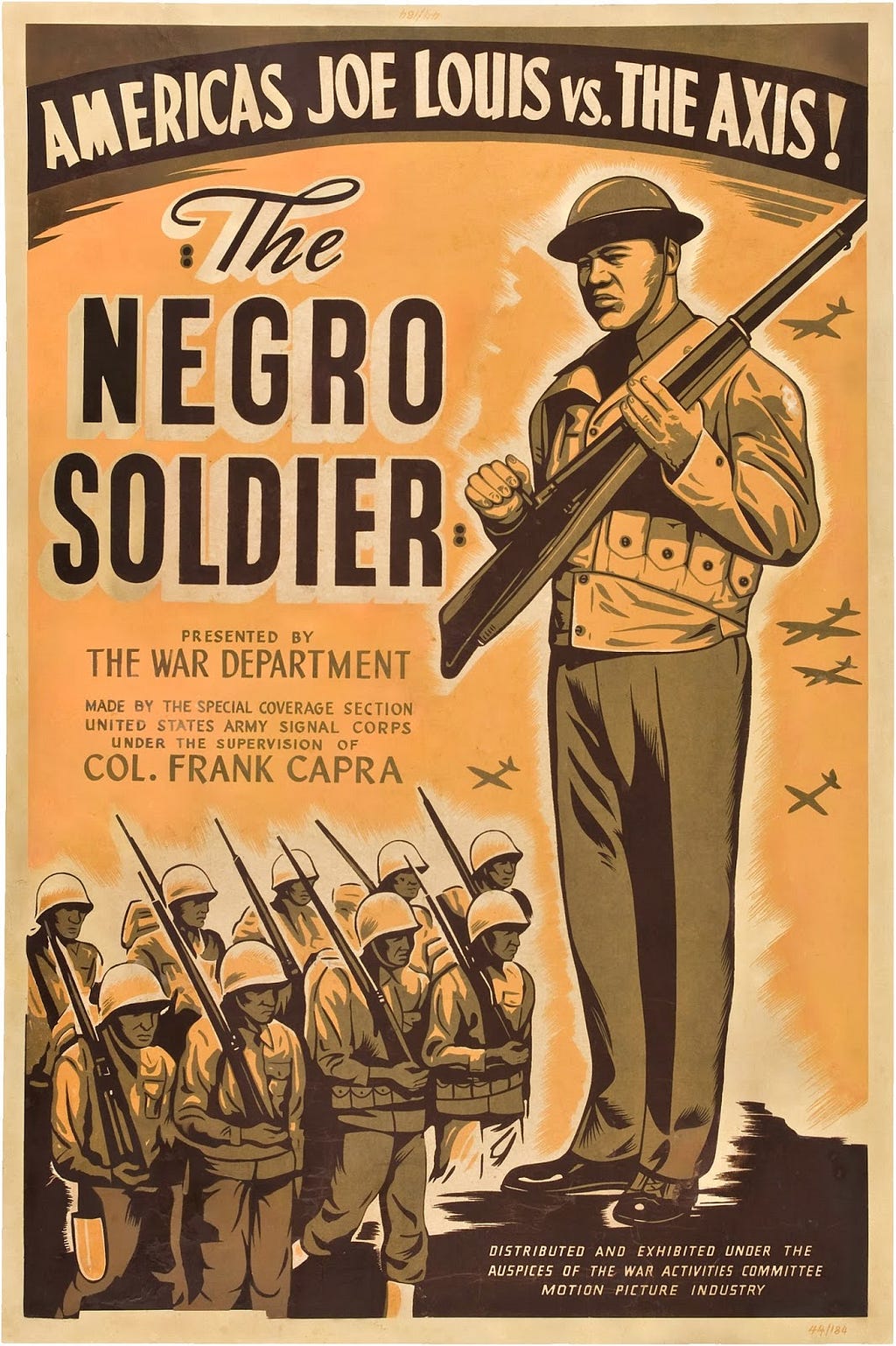

Projects such as The Negro Soldier, first dreamed up as recruitment tools to demonstrate the diverse roster of America’s enlisted men, also threatened to highlight the country’s fractured nature, something which the military couldn’t afford to lay bare. In its finished form The Negro Soldier, aimed at recruiting African-Americans to the war effort, earned favorable reviews from such black luminaries as Richard Wright and Langston Hughes. But as its writer Carlton Moss was aware, the film had been tailored to ignore certain realities, playing down the discrimination that continued to characterize life inside the segregated barracks. Similarly, the informational documentary Know the Enemy: Japan (directed by Capra) relied on cartoonishly racist images, reflecting the nation’s predominant anti-Japanese sentiment, which had spurred the internment camps where Japanese-American citizens were held until the end of the war.

At the other end of the spectrum was John Huston’s Let There Be Light. The 1946 documentary, which dealt openly with what is now termed post-traumatic stress disorder, was suppressed by the War Department for over thirty years. Its images — of soldiers scarred by what they witnessed in combat, and tenderly and empathetically shot by a director who was more associated with American masculine bravado — openly challenged the idea of exultant, victorious soldiers returning home from the war.

Postwar American myth-making happened at the movies. The same generation that was fed such patriotic studio-made calls to arms as Mrs. Miniver and Casablanca were simultaneously forced to reckon with the devastating images presented in documentaries like The Battle of Midway (1942), Prelude to War (1942) and The Battle of San Pietro (1945). The five directors highlighted in Five Came Back blurred the lines between fiction and documentary storytelling (most of the Battle of San Pietro, for example, was staged, as were a number of scenes in many of the newsreels the army made available during the war). In so doing they revealed an unavoidable truth: that Hollywood filmmaking was intimately tied with, and often times dependent on, a myopic vision of American exceptionalism.

As Fox News viewers are treated to footage of the Mother of All Bombs being dropped in Afghanistan, with Toby Keith’s “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)” playing in the background, there seems to be no better time to revisit that other historical moment when moving images were deployed towards political ends. The United States remains a country shaped by movies, a fact nowhere more apparent than in those early war films which sought, for better or worse, to frame the army, the war and its aftermath to Americans of an entire generation.

“Our films should tell the truth and not pat us on the back,” George Stevens said in 1946. Otherwise, he wondered, “isn’t there the slight chance that we might be revealing America as it is not? Would that be encouraging us in our own delusions about ourselves?”

Giving Us Back to Ourselves: Jeanette Winterson on War