Interviews

“HoodWitch” Celebrates the Power of Black Femme Witchcraft

In their new poetry collection, Faylita Hicks communes with mothers, children, ancestors, and gods

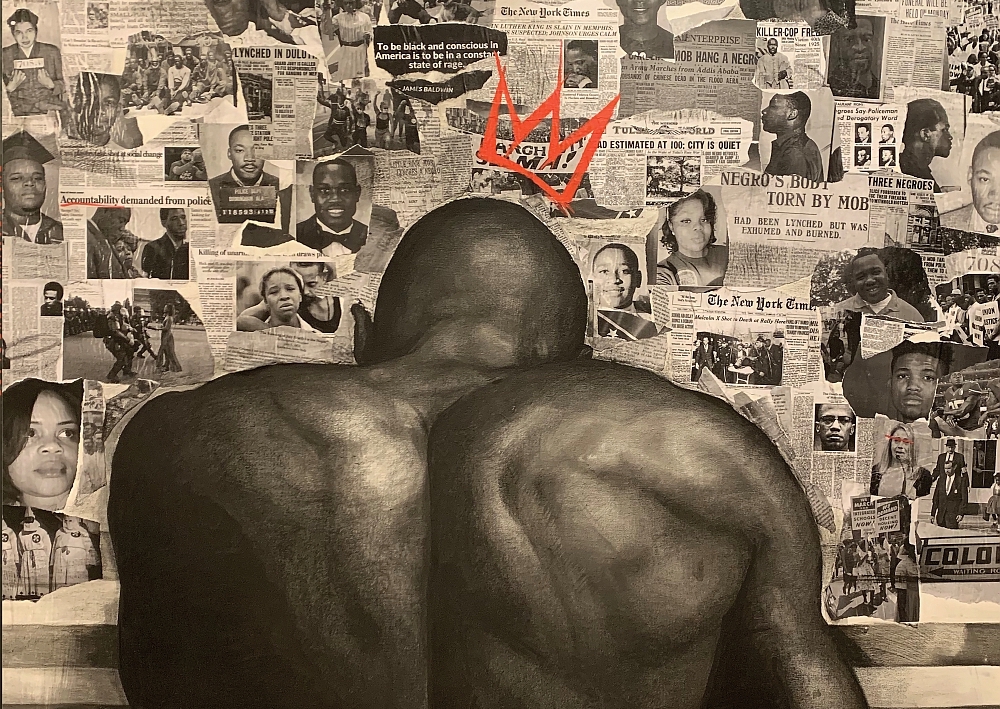

Faylita Hicks’s debut poetry collection, HoodWitch, is about the Black femme body. These poems explore Black femme power and the reclaiming of those harmed bodies described as “something that can & will survive / a whole century of hunt.” Organized by sections based on three Haitian Voodoo veve images—Papa Legba, Maman Brigitte, and Baron Samedi—HoodWitch sets an immediate tone with a poem that works as a prologue entitled “About the Girl Who Would Become Gawd” about the connection between Black womxnhood and the policing and politicizing of said body—“all fear in the body.” It ends in binary code that says, when translated, “Say Her Name, Say My Name.”

The rest of the collection calls upon the spirit of mothers, specifically Hicks’s mother and their own experience of motherhood, through a series of poems based on childhood photographs. Readers get an experience that is personal yet universal. Hicks’s poems are about giving their child up for adoption, mourning their fiancé, and embracing the nonbinary femme body through a miasma of language and imagery that conjures Christian, Afrofuturist, and Voodoo mysticism; it’s all beautifully visceral and real.

Faylita Hicks is a 2019 Lambda Literary Nonfiction Fellow, a 2019 Jack Jones Literary Arts “Culture, Too” Gender/Sexuality Fellow, and was a finalist for the 2018 PEN America Writing for Justice Fellowship. Their poetry and essays have appeared in Slate, Huffington Post, Texas Observer, POETRY magazine, Adroit, The Rumpus, and others. They are the managing editor of the Austin-based literary journal Borderlands: Texas Poetry Review. They work in criminal justice reform as an organizer and writer with the social justice nonprofit Mano Amiga.

I spoke with Faylita about their practice as a witch, their meaning when they talk about “Gawd,” and the publishing experience of a Blxck poet (and why they use the word “Blxck”).

Tyrese L. Coleman: I read your entire collection and feel as though you have me spellbound. Are you a witch?

Faylita Hicks: Yes I am. I have a personal practice that I adhere to—though my family does not necessarily agree with my practice. It’s a practice I’ve developed using personal research and intuition.

TLC: You have a poem titled “Hex for R. Kelly.” Did you put this hex on him? Please say you did.

FH: This hex is real, though I haven’t actually performed it. I have considered the implications of performing this work on R. Kelly and have only recently decided that it is pertinent. I work under the concept that moving such a major negative energy, such as a hex, could mean that I receive such energy back onto myself—but I think the pain and aggression he has put on Black girls and womxn is substantial enough that it should be carried out. Honestly, I believe I will not be the first person to do such work and that what we are seeing in regards to this case is actually the work of many practitioners already. My casting would only add to it.

TLC: I ask about your practice because I’ve seen an emergence of Black witch iconography and a desire to see more Black witchcraft in media—or rather, this feeling of asking the world not to forget about Black witchcraft.

This is not new and I am not the first, I am one of many.

FH: Black witchcraft is not new and I believe it is only “trending” because Black witches are making themselves known and are reaching back into their historical origins to reconnect with their ancestors in a more genuine and public way. This is not new and I am not the first, I am one of many. Truthfully, Black womxn and femmes have been doing this work for many generations. Whether we are adhering to cultural norms (such as not splitting the pole or blessing a meal), we are reaching back to traditions that have existed long before us, many rooted in what we now refer to as Hoodoo or Voodoo.

As a reference point, a friend, a Black Catholic woman, asked me to bless my house with holy water and light several blessed candles. That is not something written in the Bible, though it is a traditional act in Hoodoo practice. She is not a practitioner, but the act itself is one that is rooted in our shared spiritual lineage.

TLC: In the notes section of HoodWitch, you reference that the book is structured around three Haitian Voodoo images: The First Rite of Water (Papa Legba), The Second Rite of Flesh (Maman Brigitte), and The Third Rite of Smoke (Baron Samedi). Can you tell me how you settled on these images? What do they mean in terms of understanding the book and how readers should interact with it?

FH: The veves that are presented represent several lesser known loss—or messengers. These messengers help the common person to access the more important loas [a Haitian Voodoo god]. They act as guides or gatekeepers. I refer to them because this book is a summoning of both earthly spirits and other beings. I wanted my ancestors to have a say in the book—this was one way to connect with them.

TLC: Many of your poems talk about “Gawd.” Who is “Gawd” and how should we understand this being or entity as we read and appreciate HoodWitch?

FH: Gawd in this text is a Black womxn or femme who has experienced some transformative event. I am recreating the method by which many historical figures have been transmuted into godly beings. In 1,000 years, should humanity still exist, these Black womxn and femmes who have been harmed by their counterparts will be recognized as the pivotal people they were in the social justice movement. Not only the memory of their names, but of what they represent to living Black womxn and femmes who continue to carry on their legacy in the work that we do.

There was nothing anyone could do to us to keep us from rising to our true and infinite selves.

It is a process I’ve thought long and hard about. If only a few texts survive, and my book is among them, how will the terror of living as a Black womxn or femme be remembered? I hope that it will be that these experiences made us more powerful than we already are. There was nothing anyone could do to us to keep us from rising to our true and infinite selves.

TLC: One of the themes I picked up on right away is this transition of girl to mother, the creation of a mother, specifically, a Black mother. To me, it felt as if the journey you depict is not the stereotypical benevolent motherly image, but rather one that feels mystical because she is worldly. Worldly in that way Christians talk about those of us who are not necessarily of “God” but I would imagine you would say worldly and of “Gawd.” Talk to me about the path to motherhood you show readers in this book.

FH: I am trying to bring attention to the terrors of motherhood, which is a hard aspect to look at. There is this underlying assumption that all women and/or femmes want and should become mothers at some point in their lives, but that is not always the desire. There should be a balance of perspectives and the allowance of Black womxn or femmes to say that this is not what brings them joy. As a birth mother, I love my child. Deeply. But it was not ever my desire or goal to bring a child into this world that needs so much work. She is not safe nor do I have an answer on how to curate safety for her, comprehensively. It is possible she will experience any of the number of things that come with being Black, a femme, and in this generation. Fear is one aspect of motherhood, we should acknowledge it and speak on it more often.

TLC: Tell me about your language choices and the decision to reject gender binaries and racial binaries with your use of the words “womxn” and “blxck” so that the experiences described represent those that include, as you say in the notes, “women from all origins.”

FH: As a nonbinary femme, I thought about what transformative language I could use to describe my experiences—since those are the only ones I can directly write about. At one point in my life, I was a girl and a woman. Then I acknowledged that I was more than that, I was gxrl and womxn. If I had been born in a different body, I may have needed to transition physically, but I did not have to. There are others who have had to—and so I must acknowledge that those who have had to exist and bring them to the table too.

Blxck was my way of including people with my tone of skin but who may identify as something other than Black. Very often when I speak about the Black experience, I am also speaking about the experience of people with a darker skin tone or who are outliers in their own communities. While this book is dedicated specifically to the experiences of those who identify as Black, I could not exclude the womxn or femmes who have had similar experiences entirely.

TLC: Where did HoodWitch come from?

Poetry is experiencing a renaissance—but it is not wholly Black.

FH: The book started in 2009, as a series of poems meant for performance. In 2010, they were poems meant for publication—but lacked the depth that I thought they required to adequately describe my experiences. They have gone through many iterations, several becoming combined pieces or truths being revealed in a couple of previously published pieces. Though I had almost a decade to refine them, the last six months proved to be the point at which I could dig in and give them the focus they needed. I received the most feedback on the project after signing the contract, and therefore was able to focus my energy on developing the manuscript just as I needed it to be. I also started working a large spell for legibility and clarity of vision. The spell lasted for three months and it took several months after to began to regain personal energy. I know it sounds very occultist to mention, but the spell helped me finish the book. I knew I needed my ancestors to guide me.

TLC: While I know what it is like to publish a book of prose, I don’t know much about the poetry publishing world. I would say that the prose world is in a new wave of a Black renaissance. Would you say the same for poetry?

FH: I brought several books by Black poets to my writing desk and regularly reached over for energy inspiration and lineage reference. Poetry is experiencing a renaissance—but it is not wholly Black. It is in all underrepresented backgrounds. The underrepresented are pushing to become the voices heard in every arena—not just poetry. What we are witnessing is a time of tangible change, what are our most recent ancestors have fought for and all of our ancestors have dreamed of. Words, a root for all change in society, have become our tools for reclaiming our dignity and respect. I see the work writers are doing, across the genre, as its own activism. We are taking space and making space for others. That is our right and our inheritance. It’s a work that must continue as we are nowhere near done. I’m grateful for the opportunity to be one of many doing this work.