Books & Culture

How America’s Checkered Past Is Being Turned into Compelling Children’s Books

A golden age of inglorious history in children’s book publishing

A picture book about the atomic bomb? A middle-school book about our first presidents and the people they owned? A fast-paced account of Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers for young teenagers?

While Donald Trump and his administration play loose with facts and figures, a substantial number of authors and illustrators are presenting American history to students in all of its gory, complicated, and fascinating glory. Akin to the golden age of realistic YA fiction that began in the early 1970s, this approach to American history veers away from what we might wish had happened to focus on what actually happened. These books grapple with volatile issues that have shaken the country for hundreds of years — among them the displacement of American Indians, the mistreatment of women, minorities, and immigrants, and governmental malfeasance — and emerge on the other side with an idealism that is energizing as well as critical and questioning.

These books grapple with volatile issues that have shaken the country for hundreds of years…and emerge on the other side with an idealism that is energizing as well as critical and questioning.

In this effort to captivate and enlighten, these books have cultural allies, most visibly Hamilton, the theatrical phenomenon that has blown the dust off of Founding Father debates and has welcomed thousands of public school students in New York City with subsidized $10 tickets. Like Hamilton, these books celebrate America’s great constitutional principles while acknowledging human flaws and conflicting perspectives.

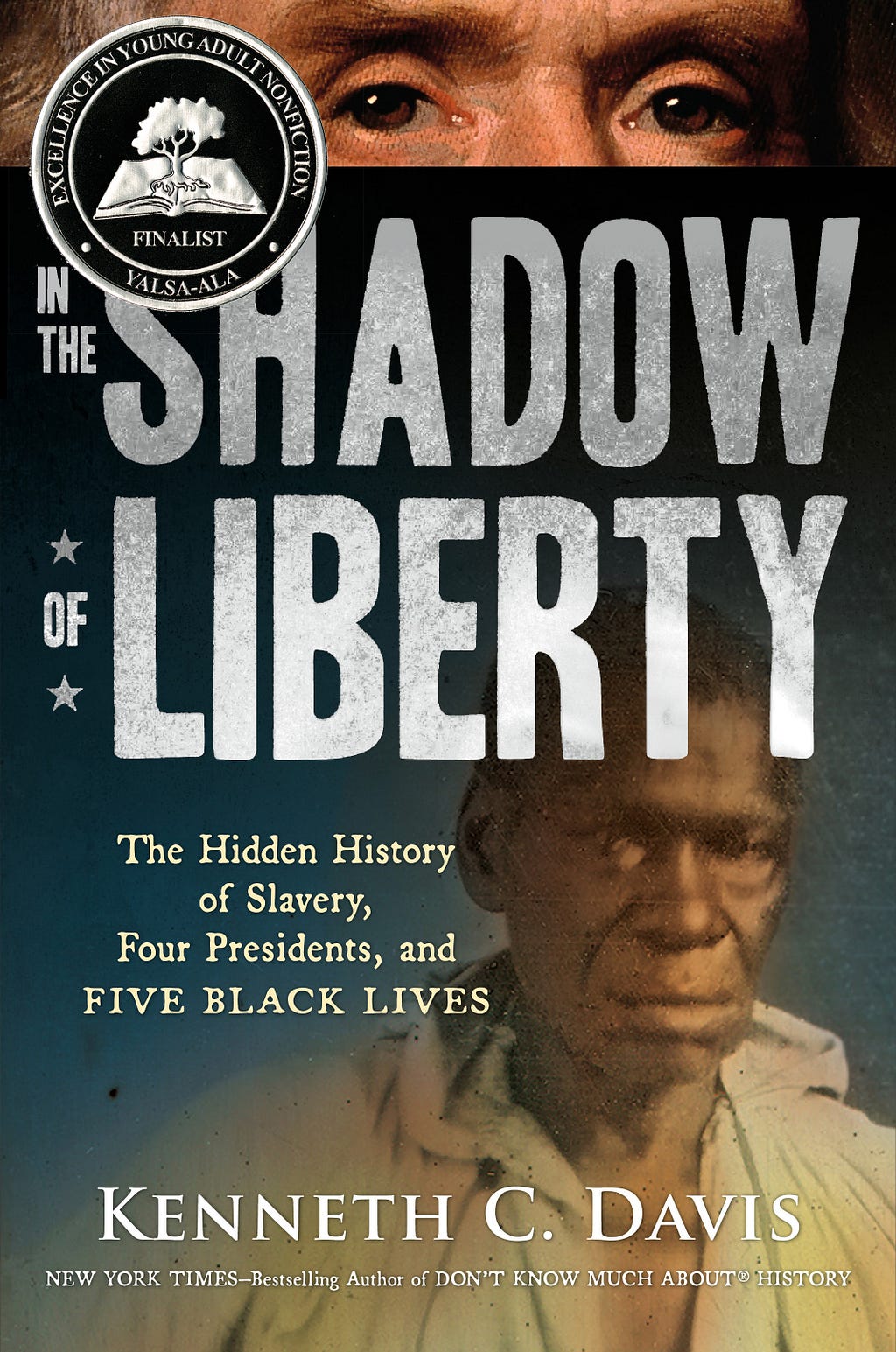

One of last year’s most compelling books for children, Kenneth C. Davis’s In the Shadow of Liberty, focuses on a basic American hypocrisy. As Davis puts it, “conceived in liberty . . . the country was also born in shackles.” Written for middle-grade students, the book documents for young readers what life was like for those who were owned by early American presidents. Although Davis describes events of two centuries ago, he effectively signals their longstanding relevance. He wants the next generation to be made aware of how white-supremacist views affected colonial society and continue to this day.

In addition to explaining how central slavery was to the United States in its earliest years, Davis recounts how five individuals — William Lee, Ona Judge, Isaac Granger, Paul Jennings, and Alfred Jackson — were involved, involuntarily, in the lives of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Andrew Jackson. For instance, young readers go beyond the usual storyline about Washington’s victory at Yorktown and find out that one of the first things Washington did after the battle was to capture enslaved people who had escaped from Mount Vernon. One of Davis’s next books will examine American Indians — “alongside slavery,” he says, “perhaps the most contentious and horrific chapter in American history.”

Young readers go beyond the usual storyline about Washington’s victory at Yorktown and find out that one of the first things Washington did after the battle was to capture enslaved people who had escaped from Mount Vernon.

Teaching about the less glorious episodes of the United States story has often come up against opposition. In one famous instance, the current Housing and Urban Development Secretary Ben Carson declared that 2014’s revised Advanced Placement American history curriculum was so “anti-American” it would inspire students “to sign up for ISIS.” That’s certainly the opposite of what Davis and likeminded authors have set out to achieve. And it runs counter to what they have experienced with young readers. Says author Marc Aronson, “It’s such a fearful image — that we would lose our kids entirely if we don’t provide this lacquered image of our past.”

Unless they are being very effectively sheltered, children and teenagers know about all sorts of human fallibility among public figures, and it makes sense to show the complexities of history early and often. Carole Boston Weatherford has written more than thirty books, mostly about African-American historical figures, and says, “We have to teach our kids the whole story. We need to understand each other’s experiences.”

Weatherford recently wrote Voice of Freedom, a picture book about Fannie Lou Hamer, who became a leading light in the 1960s civil rights movement. Born poor in the Mississippi Delta, Hamer was unaware she had the right to vote until she was in her forties. Says Weatherford, “Kids can gain inspiration from her because she was such an unlikely heroine. . . Her life shows that we need to know more. The more you know, the more you can advocate — not only for yourself but for your family, for your community, and for your fellow citizens in the world.”

Voice of Freedom describes not only Fannie Lou Hamer’s hard-earned victories but also the injustice, grief and physical pain she experienced. Ekua Holmes’ vibrant collages depict Hamer’s loving family relationships as well as her brutal beating in prison. “I don’t censor the truth or talk down to children,” says Weatherford. “I know they will ask the right questions.” She remembers discussing one of her previous books, about the segregated lunch counters in the South, with children in North Carolina: “One of the boys in the audience said, “Who made that stupid rule?” And that is the reaction I expect kids to have. The next challenge is to keep infusing that into our culture.”

“One of the boys in the audience said, “Who made that stupid rule?” And that is the reaction I expect kids to have. The next challenge is to keep infusing that into our culture.”

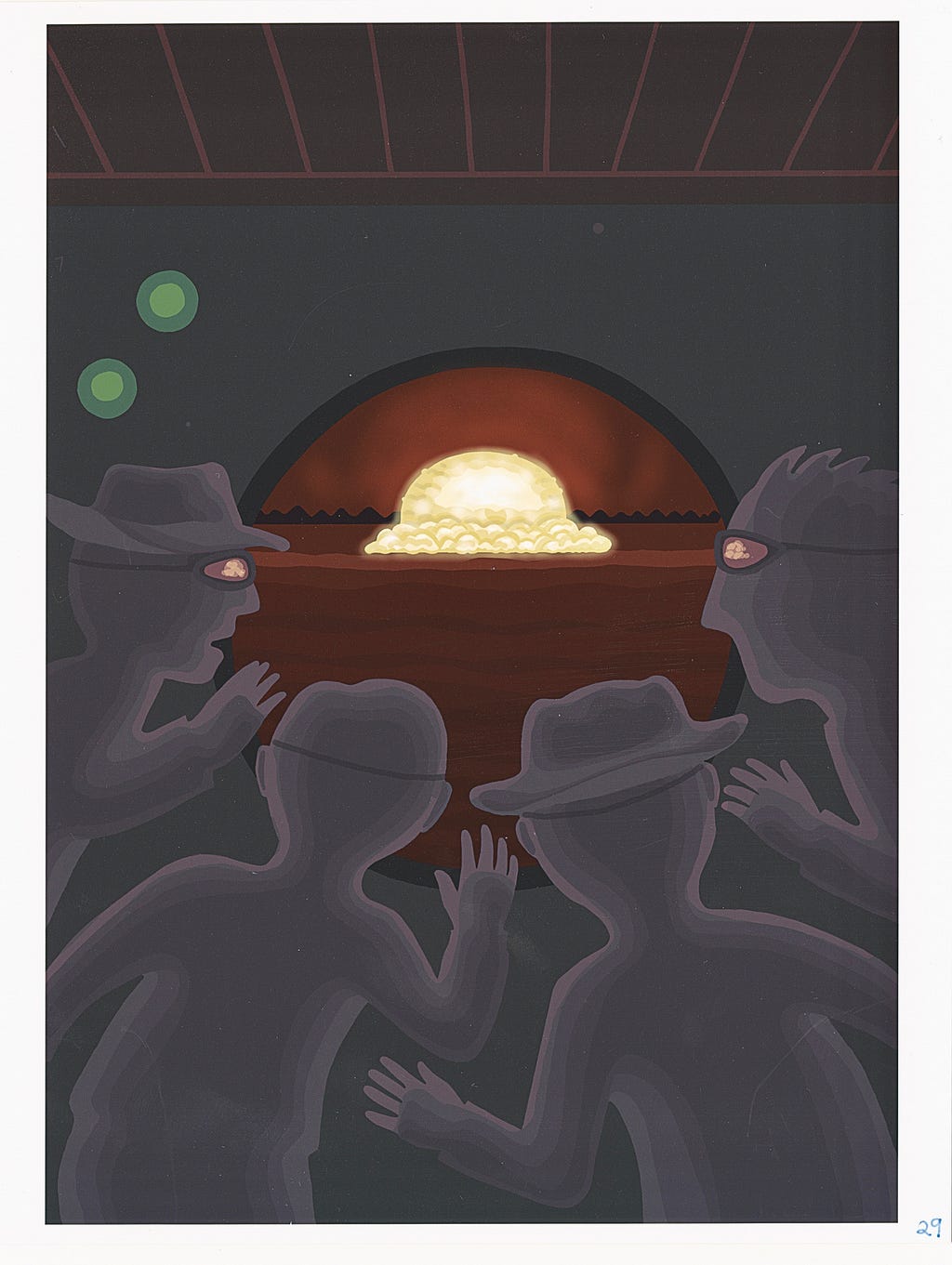

Other picture-book authors have also found engaging ways to handle difficult topics. How difficult? Last month’s picture-book releases include one about lynching (Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Power of a Protest Song) and another about the American development of the atomic bomb. The Secret Project features stunning illustrations by children’s book legend Jeanette Winter and a spare, powerful text by her son, Jonah Winter. Says the younger Winter, “The book is intended for very young readers. But it is by no means intended as a bedtime story. I see no reason why every nonfiction picture book has to have a happy ending. Why not encourage children to think? Or to learn about the parts of their cultural history which are not so virtuous? If we keep whitewashing the ignominious chapters of our history, then basically we are continuing to create successive generations of adults who don’t really know or care about the dangers, for instance, of nuclear proliferation.”

Steve Sheinkin, another author who labors to produce a nuanced, richly researched view of American history, started out as a textbook writer. The work soon frustrated him since he wasn’t allowed to include the full stories of figures like Benedict Arnold. The editors told him to describe Arnold as a traitor and leave it at that. “And I thought,” he says now, “that is what’s wrong with how we teach history. Number one, we’re wasting a good story and making it boring. Number two, that’s not how it was. This guy was a hero and a villain.”

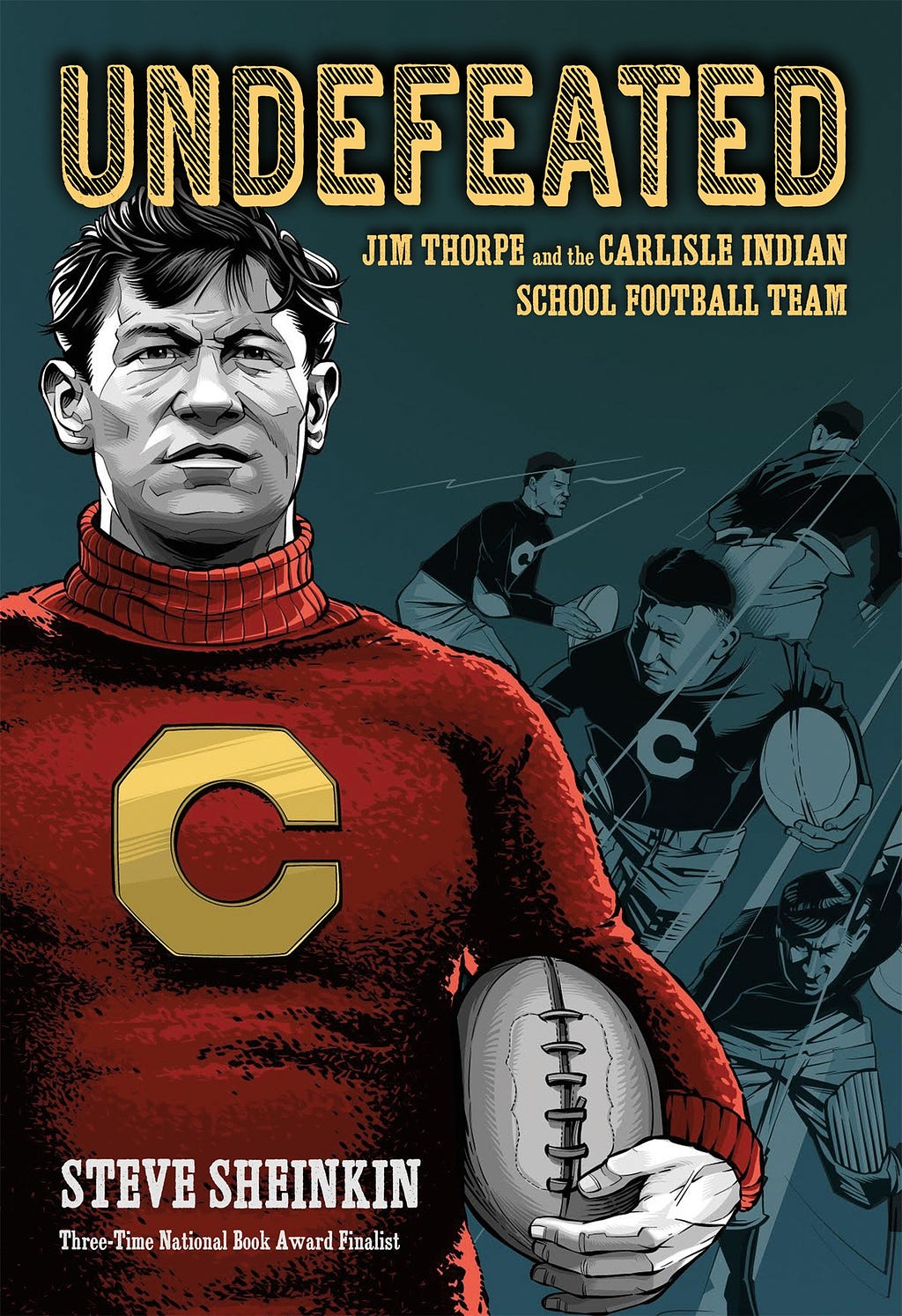

Sheinkin abandoned textbooks for narrative nonfiction, going on to write gripping books on such topics as Benedict Arnold, America’s quest to create the atomic bomb (Bomb), a dismaying miscarriage of justice during World War II (The Port Chicago 50), and a Vietnam War whistle-blower. In this last book, Most Dangerous: Daniel Ellsberg and the Secret History of the Vietnam War, Sheinkin explains in thriller-like fashion how a dedicated cold warrior turned against the war and leaked classified documents, leading to a landmark First Amendment decision by the Supreme Court in 1971. Sheinkin’s new book, Undefeated: Jim Thorpe and the Carlisle Indian School Football Team, not only tells a rousing sports story but also discusses some of the government’s shameful actions concerning American Indians.

“Number one, we’re wasting a good story and making it boring. Number two, that’s not how it was. [Arnold] was a hero and a villain.”

Just as Sheinkin invigorates his historical narratives with elements of mysteries and detective stories, other children’s-book authors and illustrators are examining America’s controversial legacies with the help of startling artwork. There is a long tradition of innovative illustration in children’s literature, and now there’s a growing urgency to depict the conflicts of the past more truthfully.

A milestone in the graphic-novel field, the March trilogy turns a personal account of the civil rights movement into a complex and fascinating portrait of brave men and women battling white supremacists. Written by Congressman John Lewis and Andrew Aydin, with dynamic black-and-white artwork by Nate Powell, the books include acts of brutal racism but also reveal the divisions and tensions within the movement. Examining two natural disasters that involved some failures of governance, author/illustrator Don Brown has created two stark and beautiful books, Drowned City: New Orleans and Hurricane Katrina and The Great American Dust Bowl, that impart personal stories alongside dismal facts.

The March trilogy turns a personal account of the civil rights movement into a complex and fascinating portrait of brave men and women battling white supremacists.

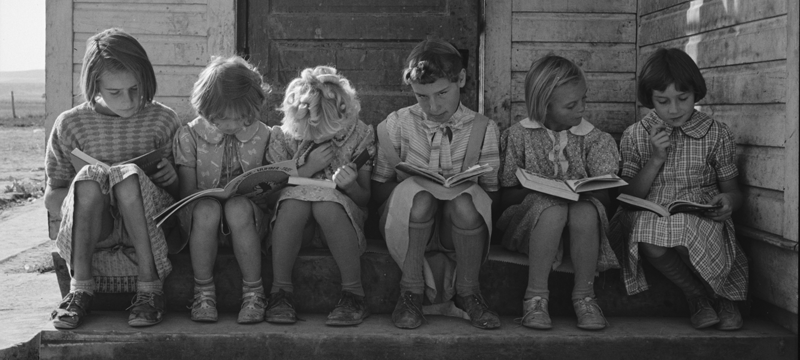

Other authors — and of course the publishers who produce their books — have deftly incorporated archival photographs into their histories. The text and images of Albert Marrin’s Flesh and Blood So Cheap, which focuses on the 1911 Triangle Fire, work together to take readers back to a time before strong labor regulations. For her lucid, meticulously researched chronicles, such as last year’s This Land Is Your Land, Linda Barrett Osborne has used old photos and documents from the Library of Congress to make distant events immediate and affecting. Says Tonya Bolden, the author of Emancipation Proclamation and many other books, “young people can be quite fascinated by history and quite engaged . . . when you help them understand that history is the context of their lives.”

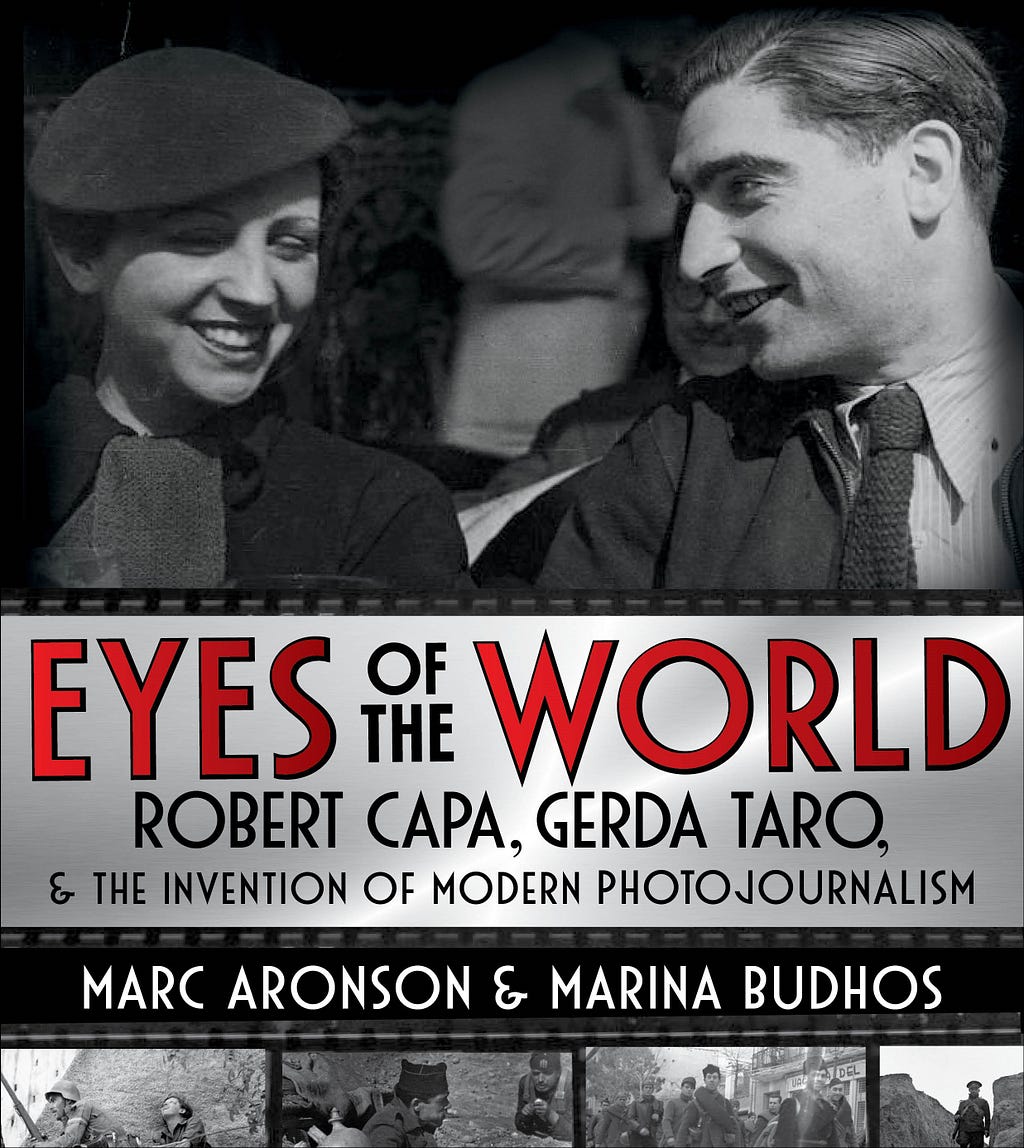

Often focusing on American history, these authors also take opportunities to show young readers that America is part of a global community and global history. Marc Aronson is currently working with author Susan Campbell Bartoletti on a nonfiction anthology about 1968 that will examine the unrest that occurred all over the world that year. Aronson has also written two books with his wife, Marina Budhos, that explain the interconnectedness of the planet and its people. Sugar Changed the World tells a story spanning thousands of years about how the sugar trade has been intertwined with slavery and science. Their forthcoming book, Eyes of the World, chronicles how Robert Capa and Gerda Taro helped invent modern photojournalism, which transmits the news of the planet to those who are interested.

Undertaken well before the bewildering presidential campaign of 2016, these eye-opening books for children speak to the struggles the nation faces on a number of fronts. Amid fake news and bizarre misreadings of history, the books offer needed correctives and honest inquiry to the next generation. At the risk of appearing to disparage Donald Trump and his appointees, their capacity to absorb lessons from history, and their leadership abilities, a quotation that’s often attributed to Frederick Douglass seems appropriate: “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

A longer list of the author’s recommended reading can be found here:

30 Books That Show We’re In a Golden Age of American History for Kids