interviews

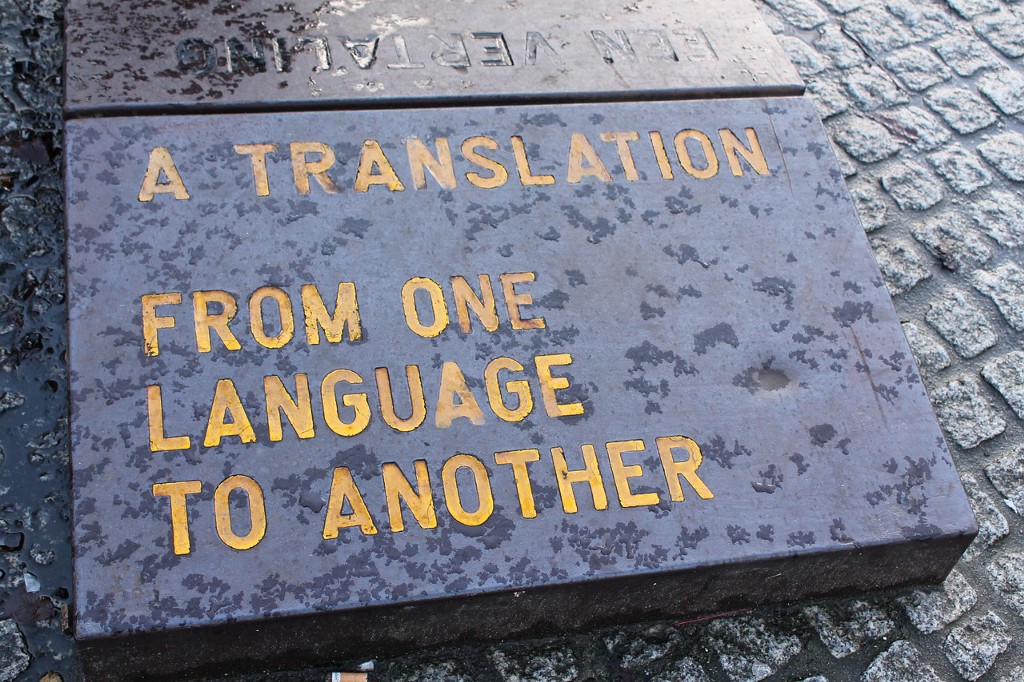

How Do You Translate a Book About Translating a Book?

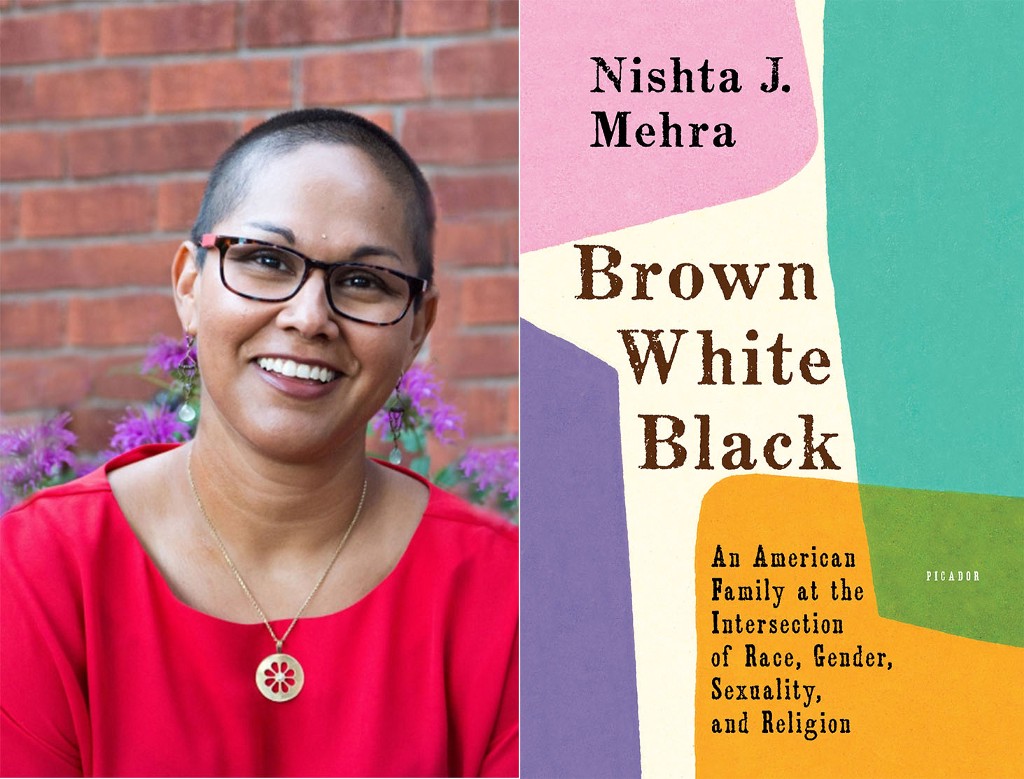

Literary translator Emma Ramadan discusses the challenges of translation, both in fiction and in reality

Emma Ramadan is one of the new generation of translators helping spotlight the most exciting works from around the world. Never one to shy away from a challenge, Ramadan’s first translation was Sphinx by Anne F. Garréta, a love story with no gender, which presents an interesting challenge when moving from French into English. Her translations focus on the writing of women, but her latest work, The Revenge of the Translator by Brice Matthieussent, examines the dynamic between translator and translated. As the idea that Americans do not read works in translation breaks down, the National Book Awards have brought back the award for Translated Literature and Amazon’s publishing wing leans into its imprint dedicated to works in translation. Emma Ramadan sat down with Parrish Turner to discuss the challenges of translation and how it can offer fascinating new perspectives on culture and place.

Parrish Turner: How does Revenge of the Translator fit in with some of the other books you have translated? What was the process of choosing this project?

Emma Ramadan: Up until this year pretty much, I was always pitching things. I heard about it when I was in my Master’s [of Translation] program at the University of Paris. At the end of the course, someone said to me “Oh you should really read this book,” and I loved it.

In terms of how it fits in with everything else, on the plot level, it is very different than the things I usually do. I am drawn to work more focused on women, non-white male authors generally speaking. I’m also very drawn to books that kind of allow translation to be shown in a different way. With Sphinx, the act of translating that book was very different than translating your typical novel. It was the kind of novel that required some finagling on my part to make sure the constraint came through the same way it did in the French. I am very drawn to the kind of project that takes translation to the next level. Although [this book] is very different in terms of content for what I usually translate, it does kind of bring up that same thing of the process of translation and the act of translation being a part of the reading experience. Because it is framed as this book translated from English into French and because of the end it is being translated back into English, I had to put my name at the end. It is an odd thing that pushed translation and the translator’s path into being something more evolved than the average book.

PT: Did the act of translating about translation affect your approach?

ER: Probably on some kind of subconscious level. I think it’s funny in the sense that this book is clearly poking fun at the idea that translators take over books and make these changes and then I had to literally change one of the character’s names in the book to be me. That feels like this kind of ironic turn at the end.

PT: Do French readers get a slightly different ending?

ER: I don’t think in terms of the way I was translating the book. I don’t think I was purposefully trying to stay super close to the French because I was trying to counteract the role of what Trad was doing and all his interventions. Matthieussent himself is a translator and it was important to me that he read the translation and that he was comfortable with it. He was sent the whole translation and shockingly, he intervened far less than other authors I have worked with. He literally just sent back “oh, you have Doris instead of dDeloris and you have this typo here” and that was it. It was like three comments. He didn’t say “oh, maybe this adjective would have been a better fit here than the adjective you chose,” which I have gotten before. He was very hands-off and went through my translation and [said] “cool, I think you got it.” It was really surprising for me, but also not surprising, because he is clearly of the mind that translators know what they are doing, because he is himself a translator and I am sure he doesn’t appreciate when authors try to give him really insane notes on his work. In terms of that, meeting with the author… was really important to me for this book.

PT: Do you usually meet with your authors?

ER: For me, the biggest benefit of being a translator and motivator as a translator is making those connections and new friends. And even if they don’t end up being my friend, having those new encounters with people whose work I really admire is hugely important. Being able to meet an author I admire and working with them on getting their book into English. That back and forth is hugely valuable and I really love that.

Unless there is an author who is not alive, then I always try and reach out and meet with them. Some of the authors I have translated I have become really close to. Anne Garréta was in Providence a few months back for a conference and she made a point of coming to the bookstore that I run, Riff Raff. That really touched me that she really wanted to see the space I was in and hear more about my life and see what my life was like. I think there is a lot of stuff that goes along with translation, but having connections with authors or with my co-translators is a huge pro. Even if they don’t speak English and can’t read my translation or give me feedback, just meeting them that feels really special. There is an immediate warmth to that relationship and it is very special.

PT: I find it interesting that you describe that relationship as warm because I think that part of what the book is talking about is the intimacy. It seems like you are describing a different sort of relationship than the narrator or the translator of this book.

ER: You mean me as opposed to Trad who is antagonistic with his author and David who is extremely antagonistic with his author. I have never had an openly antagonistic relationship with any of the authors I have worked with. I definitely have had little arguments here and there. If there is an author who also speaks English who also feels very strongly that a certain phrase should be translated a certain way I don’t necessarily agree with that. It can get a little heated, but I have never planted a bomb in an author’s home or stolen an author’s girlfriend.

It can get a little heated, but I have never planted a bomb in an author’s home or stolen an author’s girlfriend.

PT: I mean, there is still time…

ER: There is always still time. I imagine there probably exist in the world translators who really don’t get along with the authors they work with. To me, all the magic of the act of translating would go out the window if I didn’t feel a connection or bond or feel just neutral toward the author. I feel like if I really openly was not getting along with the author, it would make translating their work more difficult and it would make me trying to make the beauty of every sentence wouldn’t make this beautiful moment it would be an ugh experience. Maybe that is why Trad is interfering so much in the author’s text, because he has such disdain for the author. Every now and then there is going to be a sentence or metaphor where you are going to think: “Oh, I wish that sentence wasn’t in here, it is so cringe worthy.” But if every sentence was like that, why would you take on that project?

PT: I read in an interview that you learned French later in life, even though your parents spoke French and didn’t teach it to you. What did learning French, especially through a translation lens, teach you about French culture? What is the relationship there?

ER: Yeah, I started learning French in high school, continued in college, and did a Masters in Paris and then went to study abroad in Morocco. I think you learn so much through translating. If I am translating a book about Paris then I am learning about Paris. I just translated a book by Virginie Despentes called Pretty Things that takes place in Paris and people are walking in the streets. You are describing different neighborhoods and learning different things from the authors that you aren’t necessarily going to learn from speaking it in the classroom. Even being there, ’cause if I go to Paris or another part of France as a tourist, I’m not going to be able to access the same things that an author would. The way that people use language; the way the dialogue is written; the slang that characters use depending on their place in society. These are things you really have to pay attention to as a translator so you can replicate it in English, which means you have to have a deeper understanding of what is going on and why an author is using certain words for this character. And why they are using slang in this instance.

I remember when I was translating Sphinx, I met with Anne Garréta for the first time. There is this scene right at the beginning of the book and you don’t know the gender or sexes of either character. The narrator is in this seedy bar in this kind of sketchy neighborhood in Paris and is described as feeling nervous. Garréta said to me, you have to understand in this neighborhood in Paris, this is the kind of people that go there and who the narrator is encountering. So if the narrator is a gay man, then they would be nervous to be beaten up by these people. You have to understand this context of Paris in order to translate it accurately to understand why the narrator is nervous. I was like, oh, that makes a lot of sense. There are certain things you have to force yourself to learn to make sure your translation makes sense. Just by translating a certain book or a certain city, you are doing a lot of research. Especially the Moroccan stuff I have translated, I don’t know that I would have been able to do it anywhere near as accurately if I had not been to Morocco. There are so many descriptions of so many kinds of places and the odor of so many different things. You might not have as good a grasp on things if you haven’t been there, but you can teach yourself if you need to from a distance.

PT: What are you working on next? What are you keeping an eye out for?

ER: I am finishing up a book for Restless Books called The Boy, in French it was La Garçon, by Marcus Malte and it won the Prix Femina in 2017. It’s about a boy whose mother raises him completely isolated from society, in the French countryside. He has never talked to anyone, never seen anyone else. And she suddenly dies and he has to figure his way out into society, if he can survive and he ends up getting enlisted in the war and all this stuff happens to him. It is, on the sentence level, probably my favorite thing I have ever translated. The sentence and the writing; I am just totally in love with it. For Dorothy Publishing Project, they are a really great small press and I am really fortunate to be doing this Marguerite Duras collection of nonfiction and newspaper writing for them. I am co-translating that with a woman from my Masters program and that has been super fun for me. Marguerite Duras is my favorite writer of all time. I don’t know how to describe it except that it is an honor. That has been really special for me. I am always looking for writing. I will never say no to translating queer Moroccan authors or authors from parts of the world people aren’t paying [enough] attention to. I have a special place in my heart for Middle Eastern [areas] and Morocco, Nagrani, Tunisian, that kind of writing, because I’m Middle Eastern and I spent time in Morocco and that is just a place in the world where my heart is. Right now I am really looking for project that on the sentence level just blows me away. The act of translating a book that is stunningly beautiful, nothing really compares to that. It just makes every minute I spend on those books enjoyable and interesting.