interviews

How Greenlander Niviaq Korneliussen’s Queer Millennial Novel Turned Her into a Literary Star

Alison Lewis talks to the author of “Last Night in Nuuk” about becoming a writer in a country with only one bookstore

In 2013, a short story competition for young writers was established in Greenland. Niviaq Korneliussen, then 22 years old, entered with an ethereal story of a woman hitchhiking across the US to San Francisco, where she meets her idol, the musician Pink, in a tattoo shop. She won. Shortly thereafter, one of her country’s only publishers asked her for a novel.

Korneliussen had always written — in high school her friends found it strange that she actually enjoyed essay assignments — but she didn’t consider herself a writer. It would never have seemed a possibility in a country with only one bookstore. Milik, the largest Greenlandic publisher, has a staff of two people.

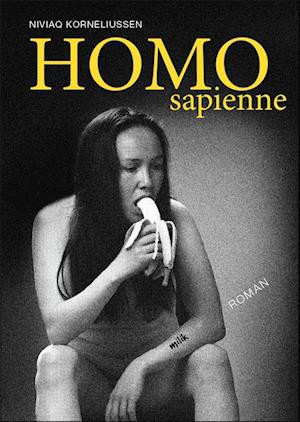

Milik published Korneliussen’s Homo Sapienne the following year, first in Greenlandic and then in the larger Danish market, translated by Korneliussen herself. The cover is amazing: a grainy photo of a woman sitting naked and unconcerned, eating a banana. Korneliussen had written the novel in three weeks, often through the night, after receiving a three-month grant from the Greenlandic government and procrastinating until nearly the last minute. The characters had been living inside her for so long, she says, that when she finally sat down to write, she couldn’t stop.

Sometimes you can feel how furiously a novel poured out of someone. I’ve felt it in Chloe Caldwell’s Women, André Acimán’s Call Me By Your Name, Violette LeDuc’s Thérèse and Isabelle. I suppose, as I write out these titles, that it’s not just the speed at which they were written: it’s the propulsion and drama of young, queer sexuality that compels one — or, at least, me — to read them feverishly, straight through in one sitting. Korneliussen’s novel is short and sizzling, narrated in stream-of-consciousness from the perspectives of five queer early-twenty-somethings in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital (population 17,500).

Korneliussen’s novel is short and sizzling, narrated in from the perspectives of five queer early-twenty-somethings in Nuuk, Greenland’s capital.

Fia is “turning old,” “dying,” three years into a straight relationship — “dry kisses stiffening like desiccated fish” — and by page 10, she has wriggled free (though first she’s forced to read her ex’s “own fucking version of how to understand the five fucking stages of loss, in endless text messages.”) Over weekends, the characters rage around, drinking, sleeping with friends and strangers, chastising themselves, waking up puking, communicating and miscommunicating in person and over text. To read this novel is to keenly remember what it feels like to be 22: in one scene, the character Sara lies in her bedroom under a “black cloud,” switching furiously between tracks on her speakers — Foo Fighters, Pink, Rihanna, Joan Jett — as each manages to only darken her foul mood.

Homo Sapienne touched a nerve. The novel was written with young readers in mind — “I wanted to write the kind of book that I would have wanted to read as a teenager,” Korneliussen tells me over Skype — but it has not been marketed as YA, and clearly is resonating with readers of all ages. It quickly sold over 2,000 copies in Greenland, a country where 1,000 copies makes a book a best-seller, and many thousand more in Danish. Translations were released in French, German, Czech, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, and Icelandic. Virago published an English-language edition in the UK in November with the (very British) title Crimson, and Black Cat, an imprint of Grove, Atlantic, released the American edition as Last Night in Nuuk in January. This makes Korneliussen perhaps the first Greenlander ever to reach an audience far beyond her island. She has found herself, over the past four years, traveling the globe.

I was surprised to hear that Korneliussen’s candid evocations of sex and sexuality did not especially scandalize readers in Greenland. Gay marriage was legalized by unanimous vote in Greenland in 2015 (the same year it passed in our Supreme Court, though less unanimously). “It’s a Christian country,” Korneliussen explains, “but we can’t really compare it to the States where Christian people are extremely Christian.” Greenland was colonized by Lutheran and Moravian missionaries sponsored by Denmark, but today, “people don’t really go to church or anything like that.” And before colonization, the Inuit people had a much more open understanding of sexuality — though, as a hunting society, gender roles were strict. Korneliussen reflects that gay men have it harder than gay women today, as the ideal of the masculine hunter still prevails. But things are changing. “I give it ten years,” Korneliussen says, “until [being gay] is completely normal.”

What did scandalize Greenlandic readers was Korneliussen’s often critical portrayal of Greenland, particularly in a chapter from the perspective of Fia’s brother Inuk. Inuk escapes to Denmark after a friend at a house party drunkenly lets slip the secret of his relationship with a male politician. The rumor quickly becomes front-page news. (In a capital of 17,500 people, one can imagine, word spreads like small town gossip.) To Inuk, Greenland feels like a “prison,” walled in by mountains: “an island that will never change,” that “has run out of oxygen.” The inmates are “so institutionalized that they stare at one another until they start to lose their minds.” In a letter to Arnaq, the friend who betrayed him, who blames her recklessness on the neglect and abuse she suffered as a child, he writes, “Stop feeling so sorry for yourself because there’s no reason that you should be pitied. Enough of this post-colonial shit.”

Greenland is an autonomous Danish territory, relying on Denmark for two-thirds of their budget (the last third comes mostly from commercial fishing). Home Rule was established only in 1979, at which point all place names were changed from Danish back to Greenlandic. The capital, Godthaab, became Nuuk. Speaking Greenlandic became a political statement of national pride, whereas before to speak Danish was to be educated and employable. One can imagine the feeling of whiplash, the fragile project of national identity, the sensitivity to narratives of victimization and to persistent Danish stereotypes, which paint indigenous Greenlanders as primitive, lazy, alcoholics and child-abusers.

Korneliussen’s candid evocations of sex and sexuality did not especially scandalize Greenlandic readers. What did scandalize them was Korneliussen’s often critical portrayal of Greenland.

“I think Greenlandic people are so used to getting criticism from Denmark that it was hard to get the criticism from a young Greenlander,” Korneliussen tells me. “You have to be proud to be a Greenlander. That has been the mentality for many years. So people asked me if I had identity issues with being a Greenlander or if I had problems when I was growing up because it’s not normal for a Greenlander to criticize.” But, she insists, a writer has to be able to criticize her own country. Greenland has “a lot of work to do.” Setting aside the precarious economy and the existential threat that global warming presents to the nation, child abuse, alcoholism, and suicide rates are alarmingly high on the island. Better for the criticism to come from someone who knows what it’s like than from “a Danish dude who has been in the country for two months.”

The character Inuk’s rage at Greenland must also be read in context; he is raging just as hard against himself, refusing to accept his own sexuality. Many young Greenlanders and, as Korneliussen explains it, Greenlanders of any age who have not yet found peace with themselves, feel trapped, and those who can afford it (travel is prohibitively expensive for many) often spend a year or two in Denmark. She herself went to Denmark for university but ultimately felt homesick and returned, which is typically how it goes, she says. You have to leave before you can decide to stay. That’s not to mention the common experience of racism in Denmark, where bars frequently refuse entry to Greenlanders. Inuk feels alienated among the blonde and fair-skinned Danes (whose conversations he also finds “boring”), and finally, after coming out to his sister, he returns home.

The population of Greenland is so small and physically isolated that it does feel cut off from the rest of the world. Travel even within the country is often made impossible by snow, and there is only one international flight out of Nuuk, to Reykjavik. At least young people today have the internet, Korneliussen notes, but language can still be a barrier. In the novel, Sara finds herself desperately googling to figure out why her girlfriend — a butch woman who ultimately finds that she identifies more as a man — doesn’t want to be touched during sex. “Why doesn’t Ivinnguaq want me to touch her”? she searches in Greenlandic. Zero results. In the English-speaking world, young people increasingly have access to literature that reifies the nuances of gender and sexuality. Though Greenlanders seem to be broadly tolerant, there is no history of queer literature or culture in Greenland; growing up in the tiny town of Nanortalik in the far south, Korneliussen did not even know that it was possible to be gay outside the very distant world of her television. Young Greenlanders today can turn to Homo Sapienne. But Sara, stuck within the novel, has no reference points. She tries googling her question in Danish. The search turns up only “hetero bullshit.”

I had a similarly fruitless internet search when I sat down at my laptop to google “history of Greenlandic literature,” and even just “Greenlandic literature,” hoping to understand Last Night in Nuuk in context. Everything that came up was about Korneliussen. After much angst and several trips to the library, I found my guide in the former school director for Greenland, Christian Berthelsen, who appears to be the only author of books on the history of Greenlandic literature in any language. Berthelsen was a great advocate for his nation’s writing; he served as chairman for several years of the Greenlandic Publishing House in Nuuk, established in 1957. But let’s turn the clock back a bit.

The Inuit people of Greenland have a rich history of oral storytelling dating centuries before colonization. Legends of heroism against the destructive forces of nature and against unseen spiritual forces, ghost stories, animal fables, and tales of everyday life were passed down through generations. As late as the 1930’s and 40’s, storytellers were busy visiting the families of their communities on winter nights. Berthelsen remembers these scenes, set in the feeble light of a small house, the steady voice of the storyteller against the howling wind outside. In a story’s scariest moments, children dove under the covers and everyone picked up their feet to sit cross-legged, for fear of what might lurk among the skins and supplies under the bed. For the most part, though, the intention and actual effect of the storyteller’s monotonous voice was to put everyone to sleep.

The Inuit people of Greenland have a rich history of oral storytelling dating centuries before colonization.

Greenlandic first became a written language with the arrival of colonialism. In 1721, the Norwegian priest Hans Egede, funded by the Danish monarchy, first set foot on the world’s largest island, learned some rudimentary Greenlandic, and began teaching people to read the Bible in their language. The first Greenlandic writers therefore were hymn writers. Handwritten Danish fables were also passed from house to house at the time, until they became too worn to be legible.

A printing house finally opened in Godthaab in the 1850’s, and the Greenlandic newspaper Atuagagdliutit (“Something to Read”), which still exists today, began printing in 1861. In its columns, for the first time, ordinary Greenlanders could speak to their countrymen in writing. South Greenlandic seal hunters described their settlements and reported on hunting accidents and weather. Danish legends and classics of international literature — Robin Hood, The 1001 Nights — were published in translation in the earliest issues. Twelve issues were printed each year, but because of the extreme difficulty of travel, they were distributed only once annually, so that both local and foreign news reached the people of Greenland a year late. “But that did not matter,” Berthelsen tells us. “They were not used to anything better.”

Thanks in large part to a period of milder weather, the turn of the 20th century brought a period of great modernization, including the advent of occupations outside of seal hunting: principally fishing and sheep breeding. It was in this period that Greenland saw its first recognized poets — the priest Henrik Lund and the organist and college teacher Jonathan Petersen — whose writing praised the beauty of the Greenlandic landscape, expressed gratitude for Danish rule, and took part in the first major debates around Greenlandic identity: should the people remain faithful to the traditional ways of life or embrace modern influences?

The first two Greenlandic novels, published in 1914 and 1931 respectively, reflect the optimism of this period and argue for the modern: both imagined Greenlands of the future — an “enlightened” population, flight routes to China and Japan over the North Pole, high rises in the capital. The first novel imagined freedom from Denmark, while the second, set 200 years in the future in 2105, still foresaw Danish rule, though with equal rights for Danes and Greenlanders.

The first novel by a Greenlandic woman was not published until 1981 (!!!). Bussimi naapinneq (The Meeting on the Bus) by Maaliaaraq Vebaek chronicles the struggles of a Greenlandic woman in Copenhagen, at a time when all Greenlanders who wanted to pursue a college degree had to travel to the universities in Denmark, and often faced racism and disorientation in the new country and culture. “Shattered illusions can lead to human tragedies,” Berthelsen writes elusively, referring, I think, to suicide. But I haven’t read this book. If you speak Danish or Greenlandic, do read it and tell me.

I kept asking Niviaq Korneliussen, as I spoke with her, how her writing reflects and defies “the tradition of Greenlandic literature,” until she had to stop and gently correct me. There simply has not been enough published to call it a “tradition of Greenlandic literature” yet. Berthelsen too notes, after all his work in chronicling it, that Greenlandic literature “is of quite modest scope to date.” A population of 56,000 — and 23,000 as recently as 1950 — simply “is not large enough to support an independent Greenlandic literature. But, that created so far is of special significance when measured with a cultural-historical yardstick.” I could not find out whether or not Berthelsen is alive today to watch Niviaq Korneliussen take the world by storm. If he is, I bet he’s ecstatic.

Korneliussen is writing against tradition, both literary and cultural. The hostility and majesty of nature is inescapably central to Greenlandic writing and storytelling, and to the Greenlandic psyche. It is what pulled Korneliussen back from her time abroad in Denmark: the calm of feeling the ocean, a mountain, and usually a fjord too within reach. And yet nature is intentionally absent from Last Night in Nuuk. So is small town life and seal hunting. Korneliussen’s characters move from apartments to bars to house parties in buses and taxis, and the reader is trapped in the hermetic feeling of any city in the winter. The characters speak, not in official Greenlandic, but in the language of young people in the capital — a mix of colloquial Greenlandic, Danish, and English (unfortunately we miss this in the English translation), peppered with text messages and, yes, hashtags.

Korneliussen’s characters speak, not in official Greenlandic, but in the language of young people in the capital — a mix of colloquial Greenlandic, Danish, and English, peppered with text messages and, yes, hashtags.

Often the characters are pulled towards self-destruction, pinned within relationships, identities, an island nation where they feel trapped. Sometimes they break free. Sometimes they find escape in their own recklessness. In one glorious scene towards the end of the novel, Sara bikes down a hill so fast that she loses control of the handlebars, and nearly mows down a couple on foot. She rounds a curve in the middle of the road; if a car comes, she realizes, she will probably die. But no car comes. She keeps on at top speed, laughing aloud, tears streaming from the wind. For a moment, she finds, “the heaviness in me is blown away.”

“I really wanted the young Greenlander to feel like she is able to live her life as she wants,” Korneliussen reflects. It isn’t easy to be different in a small place. She thinks about all the young misfits in her very young country, still wrestling with its own identity as they wrestle with theirs. “Yeah,” she says. “It was important to me to give hope.”