essays

How Immersive Theater Is Bringing Intimacy Back to Entertainment

Instead of passively observing the story, audiences at these shows are swept up in human interactions

“Where is Narnia?” I joked as I stepped through the back of the large wooden wardrobe featured in the center of a Lower East Side basement. I didn’t actually expect to find myself in the magical land of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, but this tour of Wildrence, a performance space home to inventive immersive projects, certainly invited flights of fancy. After exiting the wardrobe, I was led down a narrow hallway filled with empty picture frames and found myself in a room of stark white walls adorned with child-like drawings. What might have happened here? Or a better question would be: what could happen?

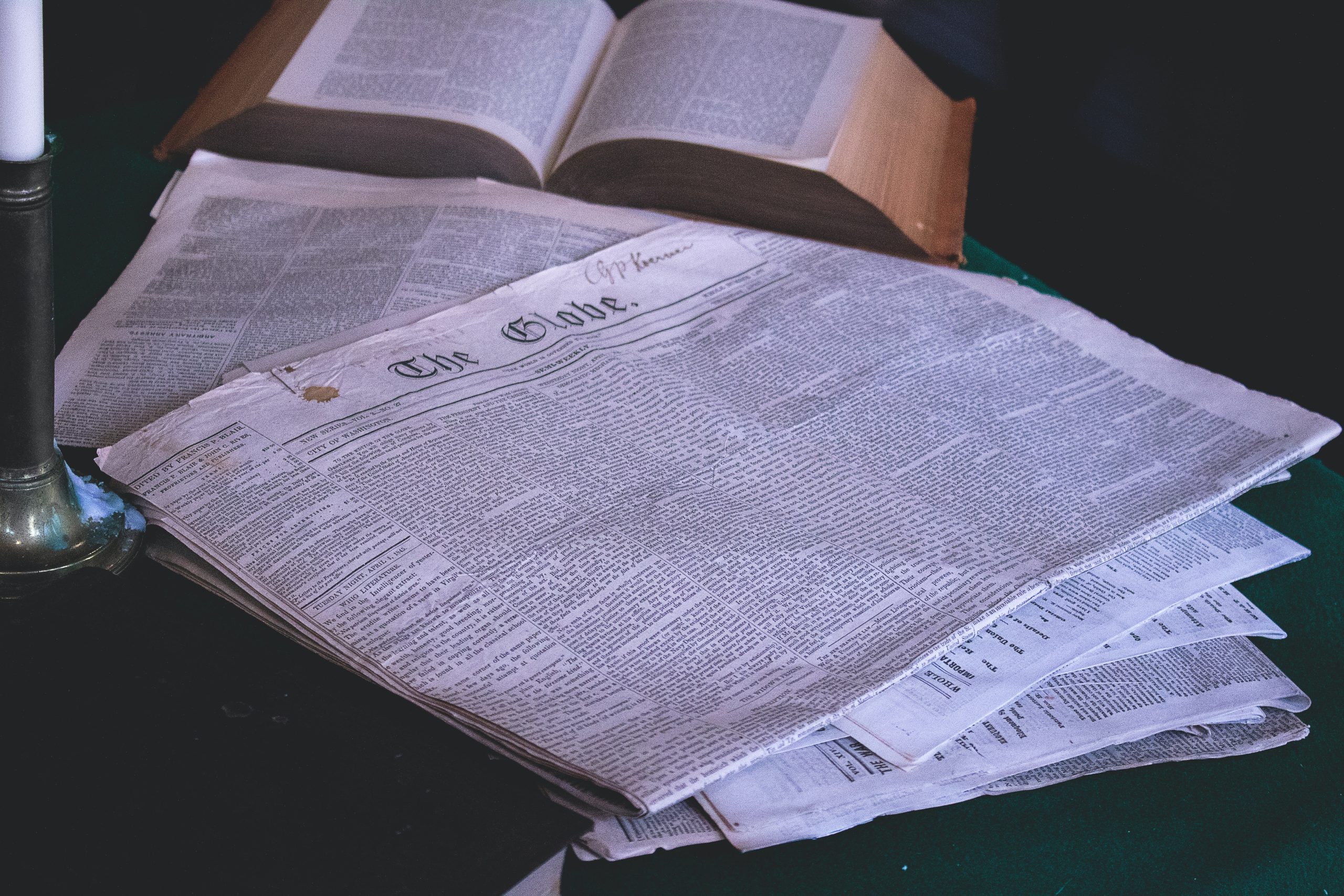

59 Grand Street is home to Wildrence, a self-described “storytelling space and consulting studio,” home to several of the site-specific interactive experiences that are appearing throughout the New York theater landscape. Wildrence’s projects include Here, which was inspired by the location’s set; The Bunker, a live immersive game about surviving the environmental apocalypse; and the interactive magic show Six Impossible Things. Currently running is Through the Wren, which invites guests to travel into a Gothic romance fairytale of the 1800s.

These strikingly different shows have all been housed in Wildrence’s basement space, a charming and eccentric series of rooms joined by a single narrow hallway. One resembles a parlor, with old-fashioned furniture and a built-in kitchen, while down a hallway adorned with empty frames is a large room of stark white walls painted with figures of humans and a library filled with books of every genre.

These settings can and do change for every production — a task quickly undertaken by Yvonne Chang and Jae Lee, former architecture students who, after working in corporate offices, decided to venture into interactive design and established their own company. The duo transformed the space, an underground karaoke bar that was adorned with peeling paint and mold when the women first found it. But the size was right for the two women, who sought to create the kind of atmosphere they experienced in escape room puzzles and at immersive theater pioneer Sleep No More, but on a much smaller level.

“From our architectural experience, we saw potential,” Lee said, adding that some guests find even the narrow staircase descending from the street level disconcerting. “We played off [people’s] notions. Each room will be a rich room, filled with content, that is used enough that it can be useful for a lot of different genres [and] productions.”

The duo worked from the ground up, converting a single room into the multi-layered world of Wildrence, complete with the backless wardrobe that did not transport me to Narnia but did inspire some flights of fancy.

The experiences offered by Wildrence — role-playing and interaction with performers and audience members — have become increasingly popular in recent years. Adventurous theatergoers have been donning ghostly white masks at Punchdrunk’s Sleep No More since 2011 and began attending Mad Tea Parties at Then She Fell in 2012. And this month they are taking to the streets and traveling through time in DUMBO, Brooklyn in Firelight Collective’s Stars in the Night. More and more, audiences want to be a part of the performance rather than simply watch it, a desire that Zach Morris, co-artistic director of Third Rail Projects, ascribes to lack of human interaction in everyday life riddled with smartphones and online interaction. The average American spends more than 10 hours a day looking at screens, so 90 minutes of face-to-face interaction, even with strangers, can have a unique impact on a person.

The average American spends more than 10 hours a day looking at screens, so 90 minutes of face-to-face interaction can have a unique impact.

“We are simultaneously more connected than we ever have been and more disconnected. The way we communicate is through screens, which are essentially prosceniums” like the traditional stage that separates the actors from the audience, Morris told me. “When we seek culture, perhaps we want to be able to engage in it in a way that doesn’t have a membrane between us and it.”

“In the last several centuries we were not able to navigate our content,” he continued. “With the advent of the Internet, we’re not only able to navigate our content but have our content be responsive in a way it never has before. I think there’s something exciting about theater and performance that can be responsive. This type of work is responsive to an audience, it is navigable to an audience and fundamentally we are hardwired to want to be in a room with another human being. We’re longing for that, I think.”

Then She Fell, created by Third Rail Projects, opened in 2012 and was originally slated for a six-week run. First staged at Greenpoint Hospital in Brooklyn and currently running at the Kingsland Ward at St. Johns, Then She Fell thrust audiences into a mysterious and fantastical environment that questions the nature of love and desire. After being checked in by a doctor and nurses holding clipboards, the 15 guests permitted at each performance are guided through the halls of the hospital, encountering characters from and inspired by Lewis Carroll’s story.

The 18-year-old company, which has focused on public and site-specific projects, sought to “blow up” accepted conventions of the structure of performances and interactions between performers and audiences with its work. As he worked to put together his first immersive, Morris realized that it was the the audience who was the protagonist in this show, which runs counter to much of established Western drama. Adjusting his way of thinking to create and compose for that kind of work caused his head to “sort of explode,” he admitted.

“We started in earnest knowing we wanted to create an incredibly intimate evening and being fine with the idea that it was going to be for a very small audience group,” Morris told me. “We were going to be throwing all the rules as we understood them out — how a piece of theater could be made, what the formula for it could be, what its business model might be… We knew that because this form was inherently fragmented, so we wanted to have some sort of underpinning, point of entry for the audience to allow them to grab on.”

That entry point became the relationship between Carroll and Alice Liddell — one that inspired controversy and many questions about its nature. Morris did not seek to offer any answers to questions about this ambiguous relationship but instead set out to explore the questions themselves. Visitors to Kingsland Ward witness the Red and White queens interacting with Alice as well as a suggestive dance between Alice and Lewis Carroll; many have their own chances to talk to Alice about the nature of love, or take dictation of a passionate letter for Carroll.

The opening of Then She Fell followed several site-specific public works that Third Rail had created, which inspired reflection and resulted in changes in their approach to creating art and how the performers and audience members could engage with each other. Combined with their interest in large-scale environmental installations, Third Rail began creating immersive work — even though, Morris said, they weren’t familiar with that term at the time.

Engaging with the actors heightened every emotion inside an already charged setting.

In Then She Fell, the immersive atmosphere inspires intimacy. As I was guided through the hospital halls, I brushed a young Alice’s hair while she asked me if I had ever been in love before. Engaging with the actors heightened every emotion inside an already charged setting of excitement and, at times, unease. Hearing a young girl speak of her fears of marriage is one thing, but assisting her in her beauty routine as she confides in you is another. And while many have speculated on whether the relationship between Liddell and Carroll was romantic in nature, watching the two engage in a sensual dance from just a few feet away is so intimate that, while fascinating, is also uncomfortable.

“As we got deeper in the process we realized we wanted to create a piece in which we were posing these questions, either explicitly or implicitly, to the audience itself,” Morris said. “What is the nature of love? What is the nature of loss? What is unrequited love? What is requited but star-crossed love? What are the forces in play that bring people together or tear them apart?”

Wonderland is far from the only world explored by Third Rail Projects, who have also presented The Grand Paradise (an exploration of youth and desire set in a tropical resort), Ghost Light (a glimpse at life — and afterlife — backstage at Lincoln Center Theater) and, most recently, Behind the City (a wistful tour through space and time in New York). Many times, the space is as much a character of the show as the personalities inhabited by Third Rail’s performers. The impact of Then She Fell was decidedly intensified by taking place in an actual hospital ward, and frequent theatergoers (including myself) were thrilled by Ghost Light’s guide through the secret halls of Lincoln Center’s performance space.

“If it is space-driven, it’s about finding the space and building the world around it. If it’s character-driven, it’s about developing that and understanding what kind of space wants to hold it,” Morris said. “Then She Fell was very much space-driven. Though we had been developing work around Lewis Carroll’s writings, it wasn’t until we found the hospital that the setting of the world became the hospital.”

Some of Third Rail’s work is inspired by characters, while others are drawn from the performance space itself. The same applies to Wildrence: the performance space was the inspiration for the content and characters of the show Here, for which producer Kelly Bartnik invited the performers to sit in the space and choose different props or locations to create a story from them. The results, including a room filled with a childhood game of sheet forts, were surprising.

Moving from observer to participant enhances any emotions the show inspires — love, loss, longing, or even confusion — a technique utilized in the recent show Stars in the Night. Firelight Collective’s show, playing in New York after a run in Los Angeles, guides groups of 12 through Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, exploring how the effects of a woman’s disappearance ripple through a community. Interactions with the wistful former lover or the frantic brother searching for his missing sibling while standing along the Brooklyn waterfront are heightened by the vast, open-air environment that is both beautiful and isolating.

Moving from observer to participant enhances any emotions the show inspires — love, loss, longing, or even confusion.

The show was inspired by the personal experiences of both artistic directors: Stephanie Feury was leaving a relationship, and Nathan Keyes was beginning one. The writing was sparked by love and loss and the locations soon followed. In Los Angeles, audiences were moved from point to point in an SUV, while in DUMBO they are guided throughout the streets on foot. The rejuvenated atmosphere of the rapidly transforming Brooklyn neighborhood, where the doorway of an historic warehouse can look directly onto the entry of a brand-new, sky-high condo, provides a fitting atmosphere for the already emotionally-charged performance in which the timing of scenes changes as well as locations.

“The story started to speak to us from a different level,” Keyes said. “We embraced the idea of taking the show to the streets and kind of laying the narrative over what was already there as a backdrop… We try to stay with the story and narrative. Once we’ve got a draft and it’s up on its feet, we start looking at the options and how the audience may respond there. Even in our first week, we tried a few different things that maybe led the audience down a road they shouldn’t go down. We’re constantly trying to tighten bolts and being really clear and trying figure out how they are going to respond and have many options for how the actors deal with that.”

As they walk through the Brooklyn streets, audiences encounter heartbroken lovers, but also siblings, children and parents. They are invited into shops, apartments and locales beneath the Brooklyn Bridge and offered snacks and cocktails. Decade pass rapidly during the 90-minute performance, but all the characters are connected — a fact the audiences may not realize until the performance’s conclusion but quickly come together upon reflection with other people who attended the same performance. Heated discussions about who, where and when each person was took place on the sidewalk following the show I saw.

“As we kind of got deeper into loss, which is death, and losing love, and embracing love, and family and the complications around it, the people and the story began to link themselves,” Feury said. “That’s also happened with the spaces. You started with one space and because of these relationships and the need for these relationships and tying them together, these other spaces were needed.”

Those spaces invited new challenges, including building the sets from scratch and performing amidst MTA traffic. Brooklyn Bridge Park is picturesque, but, it’s also the location of loud subway lines (that often run off-schedule) and real-life encounters with tourists. As one performance paused under the bridge to listen to a character frantically search for his sister, a police car and ambulance pulled up and began questioning the audience members. Much to everyone’s relief, the actor was able to stay in character.

As adventurous as an immersive show may appear to an audience member roaming the halls of a hospital or the streets of Brooklyn, the productions are well-oiled machines, with precisely-timed interactions moving from one moment to another. But actors are prepared for the unexpected, especially if audience members return to the venue determined to show off their knowledge or arrive intoxicated — two scenarios that took place during performances at Wildrence, one of which required the person to be escorted from the performance.

Unruly audience members or not, no two performances are alike — a distinction Morris said Third Rail Projects strives to cultivate with each production. While certain characteristics, such as sensual dance performances, appear across Third Rail’s different projects, the company strives to reinvent its approach with each new show.

Lee and Chang share that goal, seeking to continue diversifying the experiences held at Wildrence so that they are challenged as much as the audiences. Lee likened the space to a game console that can invite audiences into a wide variety of experiences, depending on their taste and preferences.

“Not only does that keep audiences seeing new things that have never been seen before, it also keeps us as creators in this perpetual growth. We can do anything, learn more things, keep growing our skill set, the next time something comes,” Lee said. “Everything that comes through, we try to pick something up from it.”

“Perhaps the biggest lesson or tool is actually how to discover what it is you want to make and craft the tools to make it, as opposed to relying on the same methodology, the same tools, to create the last piece,” Morris said. “How do you blow the formula up and be like, ‘I want to make a piece of work unlike anything I’ve ever made. What are the tools I need to make them? Let’s craft those tools.’”

Those tools have evolved over time, as immersive theater’s popularity has risen. Inviting people to participate rather than merely watch expands the potential for a variety of experiences. Audiences aren’t content to just sit and watch anymore. They want to be a part of it — evidenced in the television shows like HBO’s “Mosaic,” which included an interactive app for viewers to engage with and the recently announced choose-your-own adventure series launched at Netflix. But immersive theater offers an even more intimate experience, as actors converse with and even engage physically with audience members. In a culture of remote cyber/online connections, many audiences are hungry for face-to-face engagement.

Audiences aren’t content to just sit and watch anymore. They want to be a part of it.

“Now audiences are OK with being touched or talked to or the other way around,” Lee said. “And they have some agency in changing the outcome of the conversation.”

That agency, and the different ways in which audiences seek engagement, is carefully crafted for the show by its creators, who never know what a guest at the show is really thinking, Morris said. Remembering that helps prevent the writers and directors from making any assumptions about how the work is perceived and ensuring respect for both the audience members and the cast — an issue reportedly taking place at Sleep No More, where performers claimed they were physically harassed by audience members.

“We believe one of our jobs in performing this work is to really create a space for them to have whatever experience they’re having, and find a way to honor their choices, the way they’re engaging,” he said. “By its nature, you are putting human beings into intense circumstances and creators need to be quite thoughtful about how you’re doing that with care and consent and with armatures in place to protect the audience as well as your performers. We’ve learned a lot about how far we can bring people with us.”

Morris credits the genre’s appeal to the intensely personal experiences the shows inspire, which, he said often differs greatly between guests of the same performance.

“There’s something profound about that. It is less about ensuring that the story is conveyed and more about can we create a space in which audience members can pull these images together in a way that is cogent and meaningful to them,” he said. “How do you continue to do that? How do you bend people’s reality? How do you make the impossible possible? How do you create a work where one person walks out [saying] ‘This is what happened’ [and another says] ‘No, that’s not what happened’ and they’re both right?”

That’s exactly what happened to me. While leaving Sleep No More, my friend and I began comparing our experiences, and they were very, very different. It almost felt like we had attended two separate productions. Wondering how I didn’t see what he did, I felt the urge to return to the show again. If I keep coming back to explore these productions, maybe one day I will end up in Narnia after all.