Books & Culture

How ‘Ingrid Goes West’ Deflates Joan Didion, the Original Millennial White Girl

In Matt Spicer’s dark comedy, the author becomes a model—and a target—for privileged, self-centered creatives

There’s no better adjective to describe Joan Didion than “cool.” The famed American essayist has long epitomized a particular brand of coolness — call it a California coolness, if you want. But even when not writing about her beloved West Coast, there is a sun-kissed breeziness to her prose. Whether writing about water dams, Doris Lessing, or the Charles Manson murders — as she does in her 1979 book The White Album — Didion’s disaffected posture has always been central to her work. Even when she’s plumbing her own personal experience, of grief, of privilege, of longing, her voice on the page remains stubbornly in control, doling out one carefully whittled description after another. The effect of her writing is to draw you in, while also keeping you at arm’s length.

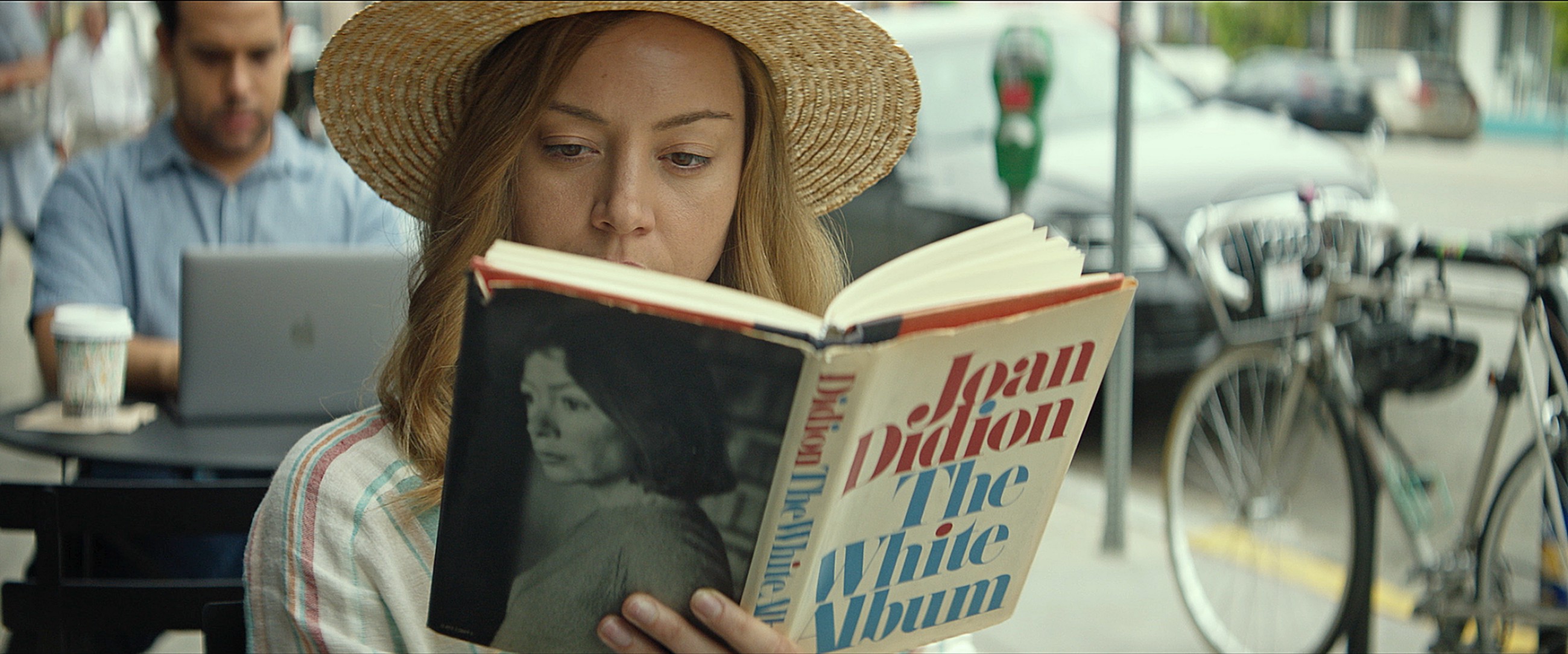

Didion’s The White Album plays a small but pivotal role in Matt Spicer’s dark comedic film, Ingrid Goes West. The eponymous protagonist (Aubrey Plaza) becomes gradually obsessed with an ultra cool, Los Angeles-based social media influencer by the name of Taylor Sloane (Elizabeth Olsen)—so much so that she moves across country to Venice Beach, stalking Taylor’s Instagram feed to learn everything and anything she can about her. That’s how Ingrid ends up eating in the same rustic restaurant where Taylor snapped a pic of her avocado toast, getting her hair lightened at the same salon, and adding the same books to her reading list. Curatorially photographed beside a matcha latte, the hardcover first edition of Didion’s essay collection catches Ingrid’s eye online, as does the accompanying quotation: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

The connection being drawn between Didion’s coolness and Taylor’s commodified version of it is difficult to miss. The California writer serves as a shorthand for the kind of creator Taylor has modeled herself after, and an emblem of the L.A. life that Ingrid soon commits herself to living. After staging a happenstance encounter with her Insta-idol and maneuvering herself into a mutual friendship, Ingrid begins to gather information that she knows will help her stay close. Upon inviting her neighbor-slash-landlord to a party, she instructs him to not talk about anything so inconsequential as his beloved Batman. Instead, her suggested topics of conversation with the too-cool Angelenos are “food or clothes or Joan Didion.”

Given the scarcity of pop culture references through most of Spicer’s film, it’s evident that Didion symbolizes a still-contemporary California vibe for his characters. But the author is treated as a mythic figure. It’s unclear, for instance, whether carefree Taylor has even actually read the entirety of The White Album (her caption is the first sentence of the essay that gives the collection its title, and is perhaps its most widely quoted line). Indeed, for the moneyed Millennial creative class which the film depicts Joan Didion is representative, a specter floating out in the cultural imagination. When he reviewed The White Album for the London Review of Books in 1980, Martin Amis wrote that “Miss Didion’s writing does not ‘reflect’ her moods so much as dramatise them. ‘How she feels,’” he posits, “has become, for the time being, how it is.” In 2017, such a sentence almost begs to be read as a prophetic distillation of the Millennial sensibility — where one’s feelings can supersede objective reality.

“A Ghost Story” is Haunted by Virginia Woolf

A similar complaint was flung at Didion by another contemporary, Barbara Grizzuti Harrison, upon the release of her essay collection. “When I am asked why I do not find Joan Didion appealing,” she wrote in 1979, “I am tempted to answer — not entirely facetiously — that my charity does not naturally extend itself to someone whose lavender love seats match exactly the potted orchids on her mantel.” Not only did Didion’s prose self-reflexively point to her own privilege — it couldn’t help but embody it, and, as Harrison further suggests, she could never seem to write anything without circling back to herself. The alluring sense that Didion probes reality with an inquisitive if always-ambivalent eye belies, to Harrison, the fact that she centers her prose on her own point of view — on what she saw, the images and surfaces that kept her rapt and through which she transports us to places she’d been, people she’d met, emotions she felt.

Through that lens, Didion emerges not only as a clear inspiration for young women like Taylor, but also as an embodiment of their artistic ambitions that came fifty years early. It would perhaps be too glib — not to mention near-sacrilegious — to argue that a young Joan Didion would have been a social media influencer who would happily have shilled for brands. But there is a degree of the carefully curated personal disclosure which she perfected that rings familiar to a generation brought up on social media. Reading her latest book, South and West: From a Notebook — a collection of notes from a trip she took South and to San Francisco in the 1970s, for pieces she ultimately never finished — gives an insight into the younger author’s writing process. Mostly that means seeing firsthand the attention to detail that’s always characterized her prose. Her jotted recollections of the places she visited and the memories they evoked practically read like captions to photos she might’ve taken — and shared — had she been so inclined:

“Oriental leanings. The little ebony chests, the dishes. Maybeck houses. Mists.”

“Climbing Mount Tamalpais in Marin County, a mystical idea. I never did it, but I did walk across the Golden Gate Bridge, wearing my first pair of high heeled-shoes, bronze kid De Liso Debs pumps with three-inch heels.”

“Corte Madera. Head cheese. Eating apricots and plums on the rocks at Stinson Beach.”

These fragments of images are not a far cry from the professional photos that litter Taylor’s Instagram feed. In fact, her social media bio could easily have been pulled from Didion’s own notes: “Treasure hunter. Castle builder. Proud Angeleno.”

What in the film seems like a distortion of the nuanced persona Didion constructed over five decades could be read as a reappraisal, in which a longstanding author is finally looked at anew. In her review of Tracy Daugherty’s biography of Didion (2015’s The Last Love Song), Meghan Daum wrote on — as her title put it — the elitist allure of the beloved essayist. The backhanded nature of the writerly investigation points to the way that Didion’s reputation may be turning. Given the tenor of many of our current conversations about American culture, Daum suggests that it’s “easy to imagine a writer of Didion’s tastes and sensibility being called out in the blogosphere and in social media as fundamentally gifted yet fundamentally ‘problematic’… in her politics and tone. For all her brilliance,” she concludes, “[Didion] might be deemed too haughty to tolerate, the ultimate white girl.”

It’s that figural image which Spicer hones in on, even as he arches an eyebrow, knowingly simplifying Didion to show the vapid nature of his own characters. Late in the film, when Ingrid’s pathological desire to live in the mediated world that Taylor projects turns dangerous, we’re given another shot of Didion’s book. Where before it had been the treasured object that brought Ingrid closer to her clueless young friend, her copy of The White Album (which she actually read!) comes to be another signifier of a life she can never have, a life that will always evade and exclude her. It seems she will forever be the girl who sits alone at home, out of money, unable to pay the bills or buy toilet paper, scrolling feverishly through her social feeds to find a semblance of a connection with those whose lives she covets.

That is, until she reaches for her copy of Didion’s book and uses it as toilet paper, metaphorically shitting on the idea of the “ultimate white girl” that Taylor-via-Didion represents, and the privileged lives they both embody. Where Taylor’s photographs and Didion’s prose project a life of carefully curated perfection, Ingrid perpetually returns us to the “real” unfiltered world.

Coolness, as Ingrid learns, requires astute compartmentalizing. It is not, as she had first gathered, an intrinsic quality but an affectation — one she constantly fails at performing. At the end, it is precisely her lack of coolness that makes her a role model in the eyes of the many young women who respond to her unruly behavior (and the frenzied videos she ends up posting on social media), and for which she appears all the more authentic. Didion may have felt that we need to tell ourselves stories in order to survive, but Ingrid’s is a different case. For her, survival depends on rejecting the need to narrativize and glamorize one’s own story, and living it instead.