Books & Culture

How Las Vegas Locals Really Feel About “Fear and Loathing”

On the 50th anniversary of "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas," three writers reflect on what Hunter S. Thompson's book means to their city

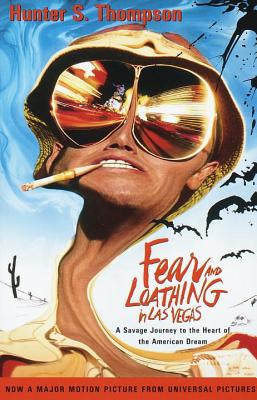

Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas stumbled into the public consciousness in 1971. Cementing Thompson as the purveyor of a new style of journalism, the book is the best-known piece of literature about the titular city. The book’s entrenchment in the canon of pop writing was further perpetuated by a big-screen adaptation replete with all the by-now-familiar images from the book: over-the-top drug usage, outlandish tourists coming to race through the desert at the sporty Mint 400, and the author’s aggressive mumbles on all things right and wrong in the world.

If there is one theme in his surreal journey at the start of the 1970s, it’s Thompson’s alternately grandiloquent and bizarre assessment of where America landed after the turbulent 1960s. He chooses Las Vegas as his setting and portrays a gaudy, greedy, and garish city as both magnet and maker of the worst triumphs of capitalism.

Determining whether this work has earned its literary standing is something that can benefit from the local voices not represented in the most famous book about their own city. Now, 50 years later, three Vegas writers examine the text against a backdrop of tourists cosplaying Thompson’s fantasy and parachute journalists attempting to report on “the real Las Vegas.” Spoiler: they come away with very different opinions.

Veronica Klash

It’s the middle of summer. As a docent at the Neon Museum, I spend most of my time in the Boneyard, the outdoor display area featuring over 200 Las Vegas signs in various stages of life. The thermometer one of the other docents snuck in has broken from the heat. The backs of my knees are sweating. That’s when the bachelorette party in matching outfits shows up. They’re wearing white bucket hats, white tank tops beneath open floral short-sleeved button-downs, beige shorts, and oversized aviators with yellow lenses. One of them has a cigarette holder poking out of her mouth. As they start posing in front of the massive Moulin Rouge sign, mimicking influencer affectations, I thank God it’s time for my break. I go inside for the cold kiss of air conditioning and to wipe down the backs of my sweaty knees.

What I see, as a former hospitality worker in Las Vegas, is a series of scenes where the narrator and his ‘attorney’ are obnoxious assholes to hospitality workers in Las Vegas.

The singular imagery and rhythms of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas may be compelling. However, labyrinthine prose and exciting illustrations do nothing to mask the staggering array of inexcusable transgressions Thompson revels in as a pseudo-protagonist and author. The characters have all the depth of a drug-filled bathtub. The plot isn’t a plot. It’s a manic, circular anecdote that leads nowhere. What I see, as a former hospitality worker in Las Vegas, is a series of overdone scenes where the narrator and his “attorney” are obnoxious assholes to hospitality workers in Las Vegas. On the page is the same entitled, rude at best, threatening at worst behavior that is often displayed by visitors in this city. The narrative rewards disgusting actions toward bartenders, front desk staff, and waitresses. And let’s not forget the violent badgering and traumatizing of a housekeeper. Is that the exciting Las Vegas experience that bachelorette party was hoping to recreate after their photoshoot at the museum?

This book is fun like holding back your friend’s hair while she’s puking is fun. The party is over. You’re there, you’re present, but all you can think about are the horrible decisions that have led you both to this moment. I made the horrible decision of reading Fear and Loathing interwoven with Battleborn by Claire Vaye Watkins. I don’t know if Vaye Watkins loves this city in the way that I do, but I know she’s lived it. Her stories are evidence of experience. Of sneaking in under the slippery, translucent skin of a place and making a home of the spaces in between. By contrast, Thompson drops on Las Vegas like a cartoon anvil dripping with toxic masculinity.

In a telling section of chapter 10, the narrator, more a paranoid mess than a person, discusses interviewing and scrapping a story about Nevada’s inmates.

Why not? They asked. They wanted their stories told. And it was hard to explain; in those circles, that everything they told me went into the wastebasket or at least the dead-end pile because the lead paragraphs I wrote for that article didn’t satisfy some editor three thousand miles away—some nervous drone behind a grey formica desk in the bowels of a journalistic bureaucracy that no con in Nevada will ever understand—and that the article finally died on the vine, as it were, because I refused to rewrite the lead. For reasons of my own… None of which would make much sense in The Yard.

This condescending and arrogant paragraph is as revealing as the book gets. The reader is not privy to these “reasons of my own”; we’re meant to trust that the unreliable narrator’s reasoning for killing the story wasn’t pride or ego, but some sort of nebulous, righteous motivation instead. This throwaway sliver is a clear portrait of the author’s attitude. Hunter S. Thompson, obnoxious asshole, gonzo journalist, iconoclast, symbol of the martyred uncompromising writer, looms larger than any of the works he produced—an image furthered by Johnny Depp’s exhaustive embodiment of the author as character in two movies. In that sense, Thompson and Las Vegas live parallel lives, their portrayal grand, exaggerated, and unnuanced, leaving behind a myth most won’t distinguish from the truth.

Rare is the occasion when anyone deems the city worthy of further exploration. They would rather rehash clichés about gamblers and neon glow.

Reporting about this town (and that’s what this book is, after all, a reporter’s take on Las Vegas) consistently replays Thompson’s narrative of wild exploits in a desert oasis. Rare is the occasion when anyone deems the city worthy of further exploration. They would rather rehash clichés about gamblers and neon glow. Don’t get me wrong, I could write a whole essay on neon glow, I love neon glow, but there’s more here. There are unique neighborhoods like the Historic Westside, recently highlighted for Thrillist by local writer Soni Brown. There are unique people, like the ones featured in Amanda Fortini’s essay for The Believer. But you wouldn’t know that from Thompson’s book or the multitude of media that followed it.

There’s no interest in telling a new story; it’s far easier to emulate one already told, to build on the familiar fiction that’s been reinforced and accepted. This is fiction that prevailed in large part (with some help from tourism campaigns) due to the reverential treatment Fear and Loathing has received and its ongoing popularity. The fiction is that Vegas is a shallow, hollow place and the Strip is the worst example of depravity and consumerism. In actuality, Vegas is an inspiring city, with folks like Kim Foster single-handedly starting a free pantry to help feed people during a pandemic. It’s a city with a pulse-hastening culinary scene that celebrates talent like Jamie Tran’s, first honed on the Strip then shared with locals on the chef’s own terms. It’s fertile ground for a creative community that refuses to be confined and defined with artists like Vogue Robinson and Q’shaundra James. It’s home to organizations like Gender Justice Nevada, that fight to provide support and build change.

I’m convinced that love for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is love for the fantasy and shadow cast by its legacy—and author—rather than any of the book’s merits. Whereas love for Las Vegas can only be conjured by the reality of the place itself.

Dayvid Figler

My family moved to Las Vegas in the Spring of 1971 from Chicago. It was a cross-country trip in a rented station wagon, decidedly drug-free beyond some industrial strength Dramamine and copious amounts of Benson & Hedges hard pack cigarettes. Once arrived, we temporarily stayed with my Uncle Izzy, a flamboyant gambler who worked days at Caesars’ Palace spinning the sucker-bet BIG 6 wheel. My dad got a job dealing a game called “Pan,” favored by older Jewish ladies, at the Sahara Hotel. This is where my folks decided to live and raise their 3-year old.

Around age 14 or 15, I remember picking up Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas at the main branch of the Clark County Library for the first of what would come to be at least a dozen reads. Had I kept a diary then, the review would have been concise:

Lives up to the hype. Of course, the guys like it—so many drugs (boring)! I love it way more because he’s right about Vegas….it totally sucks! Also, Circus-Circus…YES!

This would have been around the book’s tenth anniversary, but by then, it was already the most essential book about my hometown—at least in my small circle of friends. Reading it was mandatory. In fact, some 40 years later, there are only limited new entries in the Las Vegas literary canon, and Fear and Loathing still comfortably rests near or at the top of any serious list. Most of the others (but thankfully not all) are by visitors who seemingly dropped in for little more than a bender or to confirm their presupposed notions. Hunter S. Thompson was no different—a tourist on a mission. Still, SOMEONE wrote about us and hit all the spots I knew well from my own adventures with my family. That’s awesome!

Now, 50 years after a station wagon came from the east and a red convertible came from the west (is it possible we both arrived in town the same day?), I no longer think Las Vegas totally sucks. Indeed, I’ve become a fierce defender of my city. And if you’d assume I’ve grown weary of the countless parachute journalists who choose to only write about the “reptilian” bombast and mostly stick to the tourist-laden Strip to support their pre-ordained narratives, you’d be right. But somehow, Thompson gets a pass from me even with his distracting, surreal hyperbole; details missed or chosen to be overlooked; and the shamelessly sparse mention of locals (apart from mocked casino workers).

I like to write about my hometown, but I also know Las Vegas as two cities. One is ours and one is theirs, and they outnumber us manyfold.

I like to write about my hometown, but I also know Las Vegas as two cities. One is ours and one is theirs, and they outnumber us manyfold. The visitors have every right to their take on a city that invites, lures and challenges them to find an experience worth their cash and repeat business—but their idea of what the city means or represents is necessarily very different from the one those of us who live here experience. Since we encourage it all to fuel our economy and repeat business, though, we are rightly stuck with the consequences, literary or otherwise.

In Fear and Loathing, I’ve come to find that the subtitle grounds the work: “A Savage Journey in the Heart of the American Dream.” As evident in the text, Thompson likely feels the dream is already dead. Died at Altamont or Vietnam or pop music or Spiro Agnew’s front pocket. He thinks Richard Nixon would make a good Mayor of Las Vegas. He stands on a steep hill in the city and laments “you can almost see the high-water mark” of the failed revolution of the free-thinkers, the explanation of which is the core of this book. And he chooses to pontificate upon all this from Las Vegas while admittedly indulging in its many offerings. Thompson, as skillful fish-taler, looks for answers to a puzzle he already solved before hitting Barstow, but damn, if it doesn’t serve as a valuable glimpse of the world at an important time from an important vantage spot.

It’s a book still worth exploring.

When Thompson calls Las Vegas “the American Dream” he does it with a sardonic howl. He revels in his fellow visitors who, maybe more like him than he’d care to admit, come here and engage in what they think is hep but is in fact old and stale and exploitive and corporate and controlled. He thinks of himself, perhaps, as the last free spirit in the playland of the intellectually dead, but misses the point that Las Vegas made a space for him, too. (I still giggle when he puts a 2-dollar bill down on the Big 6 game). He’s savage all right, skewering heartless casino executives and their dutiful goons, patsies, and shills (including the cops). It’s verifiably a true thread of Las Vegas, yet not a fully-fashioned yarn. Obviously, there’s more to Las Vegas than what Thompson “reported” in his week-long journey, but he does a memorable job at taking some unflinching snapshots through a free-thinker’s lens.

When Thompson calls Las Vegas ‘the American Dream’ he does it with a sardonic howl.

The book has value because Thompson was spot-on in choosing Las Vegas to observe America transitioning out of the hopeful ‘60s, Las Vegas as stuck in ‘50s, Las Vegas as place where Americans come to merely “hump the American Dream.” Intuitively, but not comprehensively, he catalogues Vegas’s sexiness as “bush-league,” its rebranding of hackneyed entertainment as hot, its promise of freedom coming with Draconian laws. In other words, he landed, like so many others from elsewhere, in the melting pot of our country’s Melting Pot. And like a Gonzo Jeremiah, he’s compelled to tell us that we should be very fearful (or is it loathing?) that we’re actually in a stew.

He hits the nail on the head that Las Vegas has somehow marketed its way into a genius compendium of artifice, hope, risk, opportunity, growth, disappointment, mundanity and resonance. And those are the keen and important insights this local Las Vegas lover needs in a book about Las Vegas. Because the two cities co-exist, the chronicle remains an entry in answering the important questions of how and why—even if it’s sometimes opaque through the comical haze of all those drugs (boring!).

Krista Diamond

At the Tin House Summer Workshop in 2020, we began our first day with a caveat: Consider that you may not be the reader for every story.

I had never thought of this, but it seemed obvious. Of course! If you have a pervasive fear of the ocean, you may not be the reader for a novel set on a ship. If you are in the midst of a painful divorce, you may not be the reader for a love story. Realizing you are not a story’s reader can inspire growth: You deliberately open yourself up to a literary experience you might otherwise disregard. Or, it can be practical: It saves you from wasting your time.

Who is the reader for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas? I have read this book twice at different points in my life and as such have been two different readers for it.

I first read this book when I was 13 and living in New Hampshire. A boy I had a crush on said it was his favorite. He seemed so worldly for a 14-year-old at a Catholic school—he smoked weed, drank alcohol, kissed lots of girls. The book seemed similarly wild. Wanting to impress him, I read it. I found it terrifying and incomprehensible. I had never left New England, so Las Vegas and the Mint 400 went over my head. I had never so much as sipped wine during communion, so the lengthy descriptions of drugs made no sense. And Ralph Steadman’s illustrations gave me nightmares. “I liked the part with the hitchhiker,” I told my crush after finishing it, and he chuckled and nodded—my first taste of a guy conveying now here’s a girl who gets it in response to my saying something generous about art depicting violence towards women.

The second time I read Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas was at 32 after five years of living in the city. Five years of tourists dressed in Raoul Duke’s signature bucket hat/Hawaiian shirt/yellow sunglasses ensemble for Halloween. Five years of Instagram posts with the caption We were somewhere around Barstow on the edge of the desert when the drugs began to take hold. Admittedly, I wasn’t looking forward to rereading Thompson’s famous text—I already bathed in its cliches every time I walked the Las Vegas Strip—but I felt I owed it to this city that I love so much, and perhaps to Thompson too. After all, everyone around me seemed to have a parasocial relationship with the idea of guy; maybe it was time to let his work speak for itself.

Before I embarked on this second reading, I took inventory of myself as a reader: I am a woman who lives in Las Vegas and mostly enjoys literary fiction. These three facts about me became the biases (if you want to conflate identity with bias) I ran up against again and again throughout the story.

There’s a case to be made for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as a critique of masculinity. But to me, it just reads as the literary equivalent of every drunk man on Las Vegas Boulevard who has groped me and called me a bitch.

As a woman, it is difficult to be this book’s reader. Certainly, there’s a case to be made for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as a critique of masculinity (and believe me, I’ve heard it from men in my own life, usually prefaced with a hearty, “Actually…”). But to me, it just reads as the literary equivalent of every single drunk man on Las Vegas Boulevard who has groped me and called me a bitch. Like those drunk men, there is no examination of male violence; there are just jokes about sexual assault. During the chapter in which Raoul Duke watches his attorney threaten a waitress with a knife, there is the beginning of a realization that could be followed by introspection (“The sight of the blade jerked out in the heat of an argument, had apparently triggered bad memories. The glazed look in her eyes said her throat had been cut.”), but it is quickly abandoned.

As a Las Vegas resident, it is also difficult to be this book’s reader. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas is a tourist’s perspective of Las Vegas. It is a preamble for “what happens here, stays here.” This is a book that gleefully tortures locals and treats the city like a lawless wasteland where the only people who matter are the ones who visit. For this reason, I’m kind of glad that none of the tourists I see dressed as Raoul Duke for Halloween in Las Vegas have ever read the book.

Lastly, there’s the writing itself, the part that those who only know the myth of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas are willfully deprived of. Thompson’s prose can be beautiful on the occasions he takes a break from long lists of drugs the characters have consumed/are consuming/want to consume—god, “the womb of the desert” is such a melancholic descriptor. In the final chapter of the book, when Raoul Duke limps onto the plane away from Las Vegas feeling like he might “either cry or go mad,” there exists a rare glimpse of vulnerability in the writing. At last, here it is, a toehold into our narrator’s heart: the morning after the night out when one wakes up, sober, and looks inward. But Thompson doesn’t give us that—won’t give us that, can’t give us that.

And that brings us back to “us.” The readers. The perennial question: Who is the reader for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas? I don’t think Thompson wrote this book for women. I don’t think he wrote it for Las Vegas either. I am not this book’s reader—and honestly, that’s fine. I don’t want to be.