Books & Culture

How “Riverdale” Turns Masculinity Into a Queer Thirst Trap

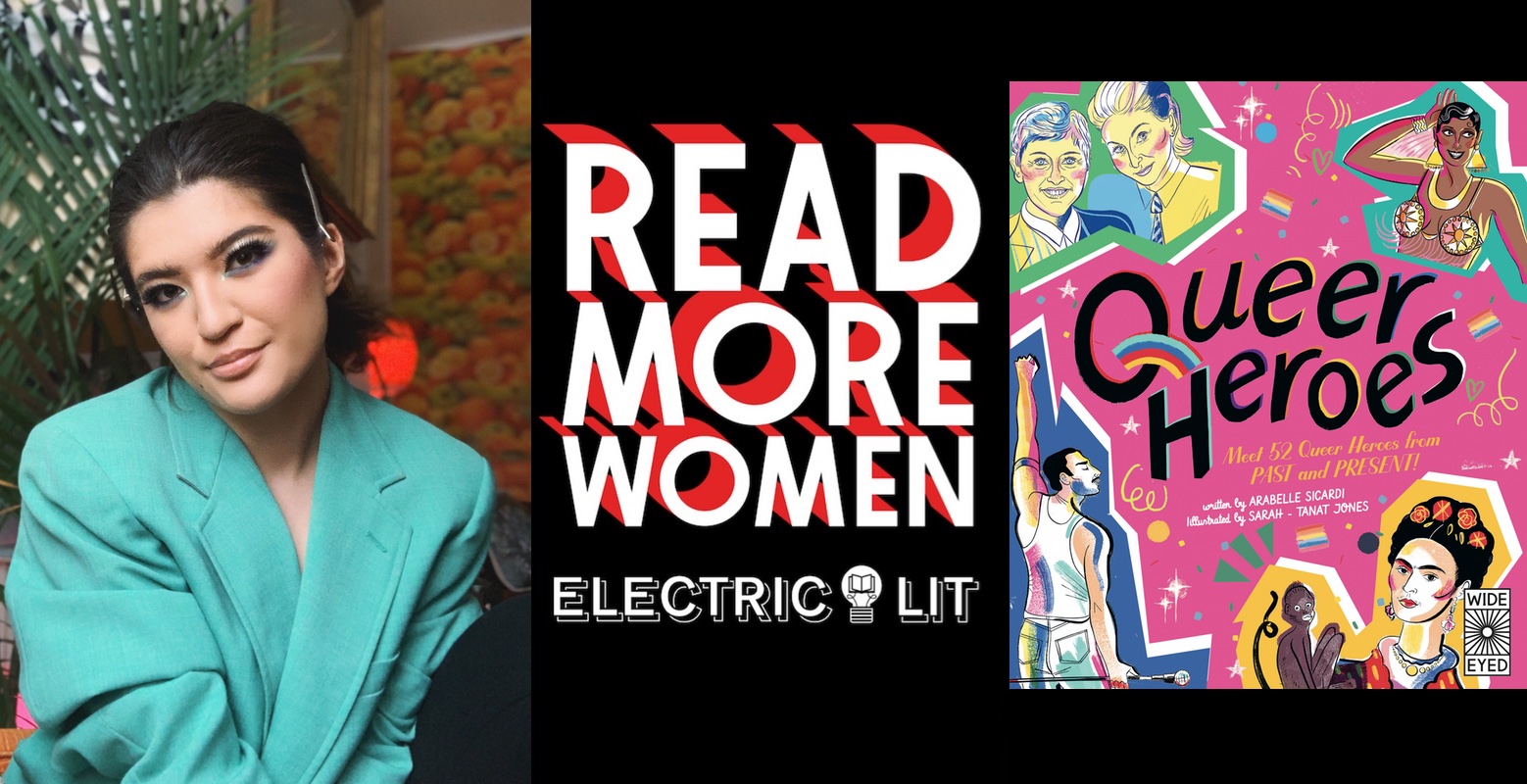

Archie Andrews offers up a one-man Village People's worth of camped-up archetypes

There’s a fine line between the image of so-called “All American” hetero masculinity and gay male eroticism. Marky Mark in a pair of Calvin Kleins. Marvel and DC’s hunky superheroes. Sailors on day leave. Frat bros sunning on the lawn. Jocks in locker rooms. Each of these images conjures up both oppressive heterosexuality and irrepressible gay allure. That’s the joke, as it were, behind the disco group the Village People: dashing young men, who co-opted the trappings of performative manliness (props and costumes for cops and firefighters, cowboys and construction workers) to embody a coded call to gay arms. And it’s the Village People who come to mind whenever I watch Riverdale.

The CW live-action adaptation of the long-running Archie comics may not appear, immediately at least, to have much in common with those campy takes on hetero masculinity. But the more you pay attention to the ways that teen drama has repurposed the Archie Andrews character (and its hometown in turn), the easier it is to see the undeniable queer sensibility that runs through this 21st century reinvention of an All-American classic. Or, in layman’s terms, in his move to the small screen, Archie became not just a walking and talking Abercrombie & Fitch editorial but a one-man Village People, and thus careened straight into gay thirst territory.

In his move to the small screen, Archie became a one-man Village People.

When he made his debut in 1941, Archie Andrews embodied a wholesome and almost inoffensive brand of masculinity. Over the years, the freckled ginger Riverdale high schooler has stood for a very specific brand of Americana: he enjoys sports, loves his car, splits his romantic affections between two iconic girls, and is otherwise a perfect example of a typical American teenager. Just as the fictional Riverdale was not an actual place but a deliberately generic Anyplace, Archie Andrews was always an imagined vision of an American Everyman, a riff on Mickey Rooney’s Andy Hardy and a blueprint for Ron Howard’s Richie Cunningham in Happy Days. In the early comics, he was a vessel for projection: a varsity letterman despite his lack of athletic physique, a top student despite his unthreatening intellect, and crucially, a hotly-pursued boyfriend despite being pretty average-looking (Rooney and Howard were his live-action avatars back then, after all). In its 21st century incarnation, the viewer is clearly supposed to look at Archie, not see themselves as him. He’s played by the perfectly-chiseled KJ Apa, a choice that turned the once unremarkable Archie into a beefcake that falls in line with how 21st century pop culture (hilariously) sees everyday teenagers in primetime soaps. Despite billing itself in its first season, at least, as a teen heir apparent to Twin Peaks, with its nondescript Pacific Northwest setting and murder mystery surrounding a washed up teenage body, Riverdale is most indebted to teen dramas like Beverly Hill 90210, teen horror flicks like Scream, high school comedies like The Breakfast Club, and even many of the WB/CW teen soaps that dominated the early 2000s like One Tree Hill. Most of Riverdale’s adult cast — Mädchen Amick, Luke Perry, Skeet Ulrich, Molly Ringwald, and most recently Chad Michael Murray — come straight from those projects, locating Archie as both endpoint and framework of pop culture’s fascination with the All-American teenager.

But under the artistic guidance of Roberto Aguirre Sacasa, Riverdale’s showrunner and Archie Comics‘ chief creative officer, that most famous Riverdale resident has also emerged as a deliriously campy example of teenage masculinity. Over the course of its first three seasons, Archie has been a star athlete and a sensitive guitar-toting songwriter, a brooding vigilante and a puppy-eyed romantic, often switching between these various poses and identities in service of the show’s increasingly wild plots (about gangs and drugs, serial killers and pagan cults). Moreover, the show has a propensity for lustfully shooting KJ Apa shirtless every chance it can, making him a walking queerbaiting machine. In keeping with the ever-shifting masculinities his Archie has embodied over the years, the teen-aimed show has made him a wrestler (in a body-hugging singlet, naturally), sent him to prison where he became an illegal fighter (in grey sweat shorts, no less), had him work for his keep in a farm moving hay (sans shirt, of course), and let him preside over a group of masked (and shirtless) vigilantes. Add in the fact that he’s actually worn a construction hat while helping out his dad, and you start to see how Archie’s version of masculinity stretches into camp: a whole beefcake calendar’s worth of hypermasculine archetypes. It’s a Village People-like array of tropes, but more modern in spirit—bad boys instead of cops. And more violent, in turn, making the once-earnest high school character into a full-blown action hero (or, perhaps more to the point, an action figure). Visually, Apa’s Archie has more in common with Tom of Finland’s illustrations of bulging, macho men than with the comic book Archie of yore.

Apa’s Archie has more in common with Tom of Finland’s illustrations than with the comic book Archie of yore.

This queering of Archie’s image is no surprise if you know about a play Aguirre Sacasa wrote called Archie’s Weird Fantasy. The 2003 Atlanta production was to follow everyone’s favorite Riverdale character, now a grown adult, as he navigated the growing pains of leaving his beloved town behind and lived his life as an openly gay man. “You did know I was gay, right?” the script has Archie ask, shortly after revealing that fellow Riverdale dweller Dilton Doiley was his first same-sex kiss. The play—which later has Archie witness the Leopold and Loeb murder (the pair of thrill-killers who went on to inspire Hitchcock’s Rope) and then move to New York City where he begins writing comic books and starts up a relationship with a Jimmy Olsen-type reporter—never quite saw the light of day. Before the production opened, the playwright and Dad’s Garage Theatre Company were served with a cease-and-desist letter. The show couldn’t go on if Aguirre Sacasa used Archie and his fellow Riverdale friends, even as the entire premise of his play depended on an attentive reframing of the “Riverdale” world that Archie had left behind—a world that could all too easily be read as a metaphor for the closet, as one reviewer put it at the time. To avoid a futile legal fight with Archie Comics, the play was reenvisioned as Weird Comic Book Fantasy, with nondescript names and references standing in for the specific Riverdale ones that had first framed the production. Archie became “Buddy,” Riverdale became “Rockville,” Jughead became “Tapeworm,” and so on and so forth. Further retooled, the play opened in New York as The Golden Age two years later.

In many ways, the elements that drove Aguirre Sacasa to deconstruct and play around with Archie in Archie’s Weird Fantasy/The Golden Age are all over his dark teen soap drama Riverdale. The campiness of the CW show is almost too cloying at times (this is a show where a line like “word is, Papa Poutine’s son Small Fry is looking for payback” is delivered with a straight face), but it’s also what’s allowed it to produce two musical-themed episodes centered on campy reworkings of iconic explorations of maladjusted teens. The show’s Carrie: The Musical and Heathers: The Musical episodes are just as bonkers as they sound, but they also reveal that at its core, Riverdale is an exercise in meta-pop culture that uses its comic book characters as launching pads for heightened discussions of what it means to be a teenager in the 21st century, when everything is a reference, everything a quoted line, everything a pose. Just as he plucked the plucky Archie from the comforts of his small-town to face more pressing social struggles in New York City (the play dealt, if obliquely, with the AIDS crisis), Aguirre Sacasa has made a point of pushing the fictional Riverdale to grapple with insidious social ills like drugs, gangs, corruption, and gentrification in ways that are surprisingly progressive. Veronica’s dad alone, for example, has been revealed to be a corrupt crime boss hoping to push out low-income households from lands he hopes to develop, a druglord intent on keeping a stronghold on Riverdale’s trade, and later still a would-be for-profit prison developer. These storylines have pushed the once family-friendly comics into more adult territory, allowing for Archie and friends to deal with real-life violent threats on the streets and also with more hormonal urges in the sheets.

While the show has clearly favored putting its characters through the wringer when it comes to portraying the underbelly of violence that runs through what seemed like an idyllic town (see: the murder that opens the show’s pilot), the drama has also sexed up characters that had, for decades, been much too prim and proper to even conceive of such a thing. It was no accident that Riverdale got Archie to have sex (with a teacher!) in its very first episode. From the get-go it was clear that this was not your (grand)parents’ Archie: the comparatively neuter Everyman — Everyboy, really; early Archie is almost prepubescently scrawny — had been transformed into a sexy hunk. That evolution feels almost too quaint. After all, hormonal teenagers are now part and parcel of contemporary pop culture; Archie is just mirroring the more frank approach to pubescent adolescents we’ve grown so used to in recent decades. (Unsurprisingly, Archie purists initially balked at this vision of a Riverdale populated with teens who had sex, with one ranting upon the show’s premiere that Aguirre Sacasa had turned “Archie characters into his own masturbatory fantasies that have no relation to the characters from the comics.”)

To titillate with such sanctified male ideals is to court a gay gaze that’s long been denied.

Apa, for his part, has embraced his status as teen heartthrob, toying with his character’s All-American image in editorial photos that make a point to remind you that this faux red-headed actor is a stud. In a shoot for GQ Australia, after being named Breakthrough Actor of the Year back in 2017, for example, he donned white socks, tighty-whities and a mesh football jersey for one pic where he’s jumping into bed while, hilariously, holding onto a basketball. In a nutshell it captures exactly why his Archie falls squarely in line with those images of American masculinity that have been both co-opted and queered to serve a gay male audience. As pop culture has gotten more comfortable with sexualizing its male stars, there remains the sense that to titillate with such sanctified male ideals is to court a gay gaze that’s long been denied.

Riverdale turning Archie into a jock, and making his body such a central fixation of the show, is a wink to its contemporary audience. A show as aware of male gazes and woke sexual politics no doubt understands the way it queerbaits its audience whenever it flaunts Apa’s abs or has him kiss another guy (in prison!). There’s a knowingness to such gestures, as if the show were intent on bracketing his masculinity and let it stand as a site for exploration: Archie, after all, has a savior complex, makes irrational decisions almost every episode, and gets away with ill-conceived plans all the time because he’s so charming, so earnest, so beloved. The vision of heteromasculinity he embodies is so stretched out to its limits that it ends up addressing and embracing a queer audience. Therein lies the show’s most significant overhaul from its 1940s roots; Aguirre Sacasa hasn’t just modernized that All-American boy. He’s made Archie Andrews into a pin-up guy whose winking masculinity cannot help but feel parodic, worthy of our swoons and laughter in equal measure.