interviews

How Swedish Immigration Law Condemned Jews During the Holocaust

Elisabeth Åsbrink on the heartbreaking reconstruction of one family’s annihilation by anti-Semitism

“Write soon. We long for your lines, especially because the post from Sweden arrives as it should. Take care of yourself. May God protect you, a thousand kisses from Mutti and your loyal dad.”

So concludes the final letter written by Elsie and Josef Ullmann to their son Otto, posted from the concentration camp at Theresienstadt in August of 1944 to Otto’s newfound home in Småland, Sweden. The next month, September, Josef was sent to Auschwitz. The following month, October, so too was Elsie. Neither survived.

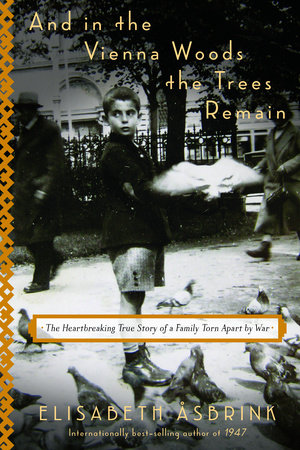

The tragic correspondence was thrust upon Elisabeth Åsbrink by Otto’s daughter, who believed that the award-winning Swedish journalist would be able to do something with the collection of more than 500 letters to Otto from his parents, two aunts, and an uncle. That something is And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain, a heartbreaking reconstruction of one family’s annihilation by anti-Semitism in both its most rabid and staid forms. Åsbrink complements the Ullmanns’ letters to Otto with archival material from state, church, and news sources, painting a complex picture of compassion and complicity, which stretches from Otto’s family home in Vienna to his adopted home in Smaland. On one hand, a kindertransport organized by the Swedish church following the Third Reich’s annexation of Austria rescues Otto from the Nazis; on the other hand, Swedish society at all levels conspires to keep Jewish adults, like Otto’s parents, from joining their children. On one hand, Otto’s adopted family, the Kamprads, come to regard him affectionately; on the other, Ingvar Kamprad, the future founder of IKEA, is all the while actively supporting the Swedish Nazi movement.

I had the pleasure of recently speaking with Åsbrink about And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain. We discussed the weight of such heavy material being entrusted to a writer, the surprising role that ABBA played in her research, how Otto’s family history resonates with her own, and more.

Arvind Dilawar: The letters from the Ullmanns to their son Otto, which form the foundation of your book, And in the Vienna Woods the Trees Remain, were thrust upon you by Otto’s daughter. Was it a difficult decision, deciding to pursue the story those letters tell?

Elizabeth Åsbrink: I really did not want to deal with the Holocaust. It’s a terrible subject. It’s something that’s been painful and I would say traumatic in my family. So I said no, I declined her offer. But then, every night when I was going to sleep, I kept thinking of this boy, this 13-year-old boy, alone in Sweden, and his parents all alone in Vienna, and these letters that went between them. And I just felt obligated.

To such a great extent, there are no graves, there are no bodies. This is one of the specifics with this genocide. OK, there are mass graves and we’ve seen the photos of the piles in the camps, but generally, six million people have just vanished, erased from the Earth. And I could, through this material, pick up five people, give them their names, their lives, their bad jokes, and I could research my way almost all the way to their deaths, so I could give them that as well. The family had no idea of the particular fates that these five people who wrote to Otto had met. I did something, at least, for these people.

AD: You mention that there’s this exchange of letters that’s happening. But you were only able to get the letters that Otto saved, so there’s no record of his replies back. Did you try to track that down? Was there any chance of getting it? Or are those permanently lost to history?

EA: The people he wrote to were murdered. I have no idea what happened to their personal belongings. The parents ended up in Theresienstadt and then were murdered in Auschwitz. One aunt and uncle were deported to this little Polish city that was overcrowded, and if they died by disease or if they were shot, I couldn’t say for sure. And the second aunt, she was taken to a woods in Ukraine and shot. So letters, if they’d kept them, if they’d taken them with them, they were not preserved. I looked in several archives for letters from Otto to other people, and I did find some of them. There was one letter that he had written that had been returned when his father was in this forced labor camp in this Eichmann project, the Nisko project. So I had one returned letter that he had written. That is all I had.

AD: An important subject that your book focuses on is Jewish immigration during World War II. Can you describe how restrictive immigration laws condemned Otto and his family in particular and Jews in general? Do you see any resonance with how immigration laws are used today?

EA: Each European country had their different twists on this, so I could briefly give you a picture of what Sweden stood for. Sweden had a very restrictive attitude towards Jews before the war as well. And, for instance, Roma people were not at all allowed into Sweden. That had been the case for some hundred years. So Sweden, nationally, their identity was very attached to ethnicity, very strongly so. I actually think it still is quite strong in that way, but it is changing, slowly. But if we talk about pre-war, it was very, very connected, ethnic identity and nationality. And they didn’t want foreign elements. This is a term that one can find in official documents, “foreign elements.” They didn’t want them in the country, so very few were let in.

In November 1938, when the Jews in Germany realized they had to get out, there was this huge refugee wave. All the European countries met to try to solve it, but no one really wanted to take responsibility, and Sweden was no better. Actually, Sweden was worse. Sweden was so afraid of getting immigrants from this refugee wave that they made a deal with Nazi Germany. They said, if you want German nationals to be able to travel to Sweden without a visa, you have to put a stamp in the Jewish passports so we can say no to them by the border, because if we let them over the border, they have to be here for a couple of months and it’s more difficult to get them out again. So Sweden actuallly negotiated with Nazi Germany and put pressure on them and succeeded. German Jews had a J stamped in their passport and, therefore, were very easy to keep out of the country. Switzerland was also in on this dealing with Nazi Germany.

But in 1943, something happened which actually changed the whole scene, one could say. It begins in November ‘42, a year ahead, when the Germans deport the Norwegian Jews. They do just like they’ve done in all the other countries: They take them out of their homes, put them on a boat from Oslo, and it goes directly to Poland. And the Swedes, then they react, because Norway is so close. It’s a “brother country,” that’s what the Swedish term is. So this was shocking. I read comments in the papers from then saying, well, I don’t really like Jews, but this is unacceptable. So suddenly Sweden woke up when it came to the Norwegian Jews. And then a year after, in ‘43, it was the Danish Jews who were going to be deported. And at the time, the opinion towards Jewish refugees had turned. When the Danish resistance movement contacted the Swedish government, it said, now we have to do something. It said, let them in. Over two nights, 7,500 people came over a strait between Denmark and Sweden, with boats, small fishing boats, any boats. And they were allowed to be there for the whole war. Sweden took care of them, gave them places to stay and school, all that. The next miraculous thing is that a lot of the Danish people actually guarded the Jews’ homes, so when they returned, they had their homes, nothing was stolen or robbed. This is a complete anomaly in the history of the Holocaust in general.

If you want to connect it to today, I would say that Sweden is still quite deep into connecting ethnicity with nationality. We have a law of citizenship that is still based on the blood principle [jus sanguinis], whilst in the US you have the [birthright] territorial principle [jus soli]. Sweden has now received a huge amount of refugees from Syria, from Afghanistan, just from the last 10 years. Since 2015, Sweden has received 170,000 refugees from Syria. I think this huge change of society, where Arabic is the second biggest language within the Swedish borders, it must lead to a change of the citizenship laws and the way that we look at nationality. I would prefer the American way. I think that’s more democratic, but that’s my personal opinion, being the child of two immigrants.

AD: How were you able to investigate the history of Austria and Sweden in the 1940s? Germany is relatively open about that time period. Is the same true for Austria, which was annexed by Germany, and Sweden, which was officially neutral during World War II?

EA: I don’t think it’s got anything to do with neutrality, these things. I found material in Swedish archives, especially about the individuals. The book is very much based on material that I found in the Swedish church archives. All the papers concerning the priest that saved these children, they are from the church archive. And that was completely open, and it still is for anyone who wants to look at it. In Austria, I found the information I needed from the Jewish community archive, which was open, but actually they didn’t want to help me because they were out of staff and under such pressure. They don’t have any money. It’s a very poor congregation. There are hardly any Jewish people left there, so they’re struggling.

Sweden came out from WWII with a sense of guilt. This sense of guilt has made Sweden welcoming to refugees to a certain extent.

There was a funny story: The guy I spoke to there, the historian, said, I can’t help you, I haven’t got the time to help you. And I insisted on going there anyway, and he said, alright, we’ll meet that day, OK. I showed up and he really didn’t want to help me, but he gave me this and that. And then I went out for lunch and he Googled me. He came to my website and he saw that I had been working on a radio show with Björn Ulvaeus, one of the guys in ABBA, the Swedish pop band. This historian loves ABBA, so when I came back from my lunch, it was a different situation. He helped me enormously. I could find out the things about Otto Ullmann’s parents, what they did in Vienna, how their life was. And that was absolutely invaluable. So thanks to ABBA, I did some good research.

AD: That’s amazing. It seems like a very Swedish story, at its heart. Ingvar Kamprad, the founder of IKEA, features prominently in your book. Now that you’re describing the changes that Sweden underwent during the Holocaust, it almost seems like he sort of captures, in one person, the two different sides of Swedish culture struggling against each other. Because on one hand, he was an active supporter of the Swedish Nazi movement and, on the other hand, he became a close friend of Otto. Is there a way to resolve that apparent contradiction?

EA: I think you’re right in that Ingvar Kamprad is a good symbol of the Swedish attitudes, but maybe not in that way, because I don’t think he changed and the Swedish attitudes actually changed. Some speculate that it was because of humanitarian reasons, others are more cynical and say that, when Hitler was defeated at Stalingrad, the Swedes saw that things were changing and also changed their policy. I think it’s probably a bit of this and a bit of that.

But Ingvar Kamprad, he was involved in the fascist movement very intensely, which was deeply anti-Semitic. And then I found that he had also been a member of the Swedish hardcore Nazi party. I don’t know when he left that party. I couldn’t find out and he himself wouldn’t comment on this information. But when I met him—which was before I found out about the Nazi party—I knew he had been involved in the fascist movement, and the fascist movement I knew for sure was very anti-Semitic. So, of course, I asked him: How did these things work together? Loving your friend, Otto, because he really did love his friend, and still being a member of this movement? And I pressured him, and finally he said, I see no contradiction.

How do you explain that? I think one explanation is that Ingvar Kamprad was not a person who reflected. He did not sit down and think over his ideas and his thoughts. He was a doer. He was a workaholic. He did amazing things, but he did not stop and think. I don’t think that was a part of his personality, and I don’t think maybe he would have created IKEA if he’d been someone who stopped and sat down and had a good think about who I am, what my ideals are. He just went on. And also you have to remember that he was born into a family where his grandmother was very dominant and she was a Nazi. She loved Hitler. And his father was also a Nazi, Ingvar Kamprad told me himself in this interview that I did. His mother was definitely not a Nazi, also important to remmber, but the democratic ideals weren’t something that was natural to him. So that’s one part of the answer.

The other is that all these totalitarian ideas need the exception. I think that any totalitarian ideology makes exceptions for the neighbor that you like, the nephew, or the bus driver or the woman in the shop. There’s always an individual that you like, because this is what’s human in us. And these ideologies can only work if you allow these exceptions. I think that’s what Ingvar Kamprad is a good example of: the exception going parallel with the ideas. And I think the Nazis were very aware of this. Himmler, when he held his famous speech in 1942 at Posen, he talked to his generals. It was time to implement the so-called “final solution,” and he said, we all know a decent Jew, but now we have to put that aside. So he was aware that personal relations and friendships were, to a certain extent, compatible with the ideology, but now, when it was time to go to the final step, he wanted them to cut off these personal feelings. That’s the closest to an answer I have.

AD: Despite some simmering xenophobia, the Scandinavian countries today are still considered relatively welcoming of refugees. Your book illustrates how this was not the case during World War II, when Jewish refugees were systematically turned away. Did something in Sweden change between now and then?

My father and Otto have similar backgrounds: assimilated big city children. And suddenly they were Jews and were supposed to be murdered.

EA: I think Sweden came out from the Second World War with a sense of guilt. It had economic dealings with Nazi Germany, and when the rest of Europe was ruined and bombed, Sweden was in a quite good place. The welfare state thrived after the war. This sense of guilt has made Sweden welcoming to refugees to a certain extent. Because it’s also the case that, when, in the ‘90s, we had a recession, it suddenly became a much more racist society. That is also the time when the old fascist movement connected with new right-wing movements, like skinheads and others, and created a new right-wing, racist group, which developed actually into the right-wing populist party that we have today, the Sweden Democrats. So they are directly linked to this fascist movement that Ingvar Kamprad was a part of. The recession in the beginning of the 1990s opened space up, and since then, we have had them. They were small and violent, and now they have costumes and have changed the way they speak and the way they see the future, but they’re still in the same corner.

AD: Early on in this conversation you mentioned that, part of the reason that you were hesitant to follow Otto’s story was because it mirrored that of your own family. Could you describe how your family arrived in Sweden? And did completing this project help you come to terms with that?

EA: Otto’s story connects to my father’s story very much. My father is a Hungarian Jew. He grew up in Budapest, very close to Vienna. I mean, they were part of the same empire, they’re like sibling cities. Just like Otto, my father was assimilated. He was even baptized because his parents thought that would protect him. Hungary was one of the first countries with anti-Jewish laws. He didn’t know he was Jewish until someone said “stinking, filthy Jew” to him when he was a child, and he went to his mother and said, what is that? But then things happened very quickly in Hungary. He is a survivor of the Holocaust. It’s a miracle that he survived. Long story, but the background is very similar: big city children, assimilated with the rational, scientific ideas of the world, etc. And suddenly they were Jews and were supposed to be murdered.

I grew up mainly with my mother, and she also has Jewish heritage. She told me never to tell anyone that I was Jewish. Never, ever tell anyone. It was like a shameful secret and if I exposed it, something very bad could happen. And this is something that she gave me without words. … It was scary to deal with this material, but I was also grown up and not under my mother’s influence anymore. But still, I had a sense of danger doing it, but I decided I wanted to. I decided it was so important and I also wanted to break this secrecy. I’m not a believer. I don’t believe in blood communities, like a folk of people, but I am Jewish. Hitler would have murdered me. That’s a terrible thing, but it’s true. Writing this book was, actually what my gay friend said, like coming out. They saw it as a coming out process, and I think they’re right, it was. I think it did change the way some people look at me, and it also changed the way I see myself.

I once went to a school and they had this book as a theme for a whole term. It was amazing. Young grown-ups—the art students had made art, and the music students had made music. And then there was quite a huge group of refugees, who were in this school to learn the basics about Sweden before they started their new life. So there were a lot of 20-year-olds, a lot of people from Iraq and Afghanistan, and we had a talk. One of these Kurdish Iraqi guys, he said it was the best book he’d ever read because everything Otto had experienced, he had experienced. He’d been sent away, by his Kurdish parents, to Sweden to find a new future and he was told to be decent, to learn the language, to get a good education, all these things. He completely identified with this Jewish fate. That blew me away, and it still does.