interviews

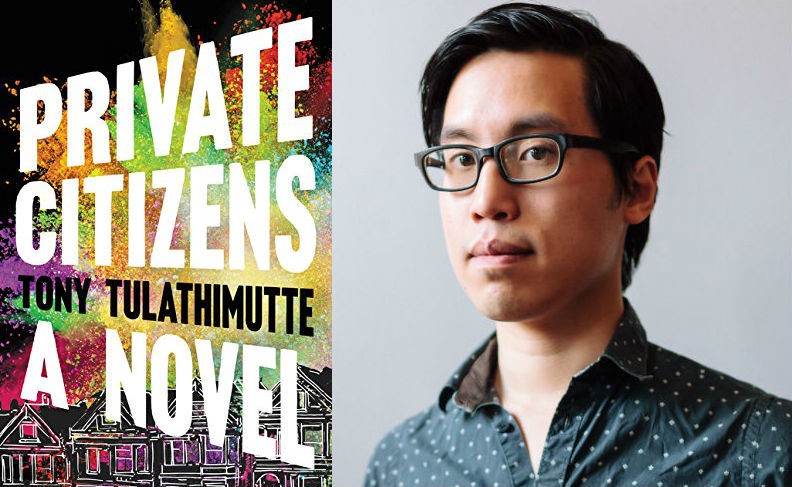

How to Have Fun Destroying Yourself: An Interview with Tony Tulathimutte, Author of Private Citizens

Tony Tulathimutte’s debut novel, Private Citizens (William Morrow, 2016), follows four recent college graduates as they flail, flail again, and flail better. The book is an uncanny mirror. If you’re an aspiring writer, a do-gooder, an Interneteer, or a human with a reasonable amount of despair, you might flush with recognition.

Tulathimutte has written for VICE, N+1, Salon, The New Yorker online, and elsewhere. I first met him at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where we both studied fiction. We spoke at a bar in SoHo about his book, empathy in fiction, “atrocity porn,” and the upside of distraction.

David Busis: This book is concerned with self-branding. Were you worried about the Tony Tulathimutte brand as you wrote it, given that there’s a memorable chapter about porn?

Tony Tulathimutte: Of course, because that chapter’s about a character who’s biographically identical to me. He’s not just Asian, not just Thai-American, but he works a tech job and lives in Noe Valley, where I lived. There are lots of obvious fabrications, but generally you think, oh, the demographics match up, that’s Tony.

So it’s funny that you bring up the “Tony Tulathimutte brand,” because the name itself is completely un-brandable, right? Nobody can say it, nobody can spell it. I think about image all the time. I feel that the Internet is neither good nor bad, it’s just a communication platform, but one that has a huge effect on the way people form their identities, and at what point in your life are you doing more identity formation than your adolescence and the deferred adolescence of your twenties? In that regard, being willing to muddy or compromise that brand is to try to upend the less savory aspects of what social technology wants us to do, which is collapse the personal and the private into each other.

Before, the person you were at home wouldn’t become public except in extreme cases. Now we not only have the capacity to be on the Internet all the time, but are encouraged to always be on, and this is equated with healthy social functioning. There’s a chilling effect on what you’re going to do indoors even when nobody’s strictly watching and you have what the law would call an “expectation of privacy.” There might even be a chilling effect on your thoughts. And it’s not because you feel like you’re being judged, but because you want to have the kind of thoughts and the kind of life that people are going to see and admire — which narrows the window for private personhood. This is what you’re meant to be doing when you’re writing, right? This is when you’re supposed to shut the door, turn off your phone, leave everyone else out of it.

DB: So do you shut the door and turn off your phone when you write?

If you wonder why people work at cafés, let’s be honest, it’s mostly to keep from masturbating.

TT: No, I don’t cut off the Internet or leave my phone at home when I go out to write. It is certainly an enormous distraction to have that stuff around, but it’s also useful sometimes to be in the aleatory mode you find yourself in on the Internet, and you stumble across things you wouldn’t think had any coincidence to what you’re thinking about, and it ends up that they do. Occasionally this distraction ends up becoming a subject. This sadly is the origin story of the porn section in my book. If you wonder why people work at cafés, let’s be honest, it’s mostly to keep from masturbating.

Sometimes I find it more interesting, rather than try and stay pure and virtuous, to instead hyper-indulge your vices. Interesting stuff comes that way too. And that was the ethos of this book. If you read any of the fiction I published before this — and I didn’t write anything new for about seven years while I worked on this — you will see well-crafted but tame stories where essentially I wanted the reader to think, “Oh, what a sensitively rendered portrait of a human soul. I feel like such a more sympathetic, kinder human being for having read it. And now I also think by extension that the author is a pretty smart, tender, caring guy.” And that holds you back.

You can get heavily praised for that kind of writing. No matter how much lip service is paid to the uselessness of art, people have a hard time letting go of this utilitarian view of literature, that it improves you somehow. They take Thomas Jefferson’s words to heart, like, “Well, literature is a mass of trash, but sometimes it can be morally instructive.” This accounts for all those blog posts that go, “These MRI scans prove that readers of fiction are more empathetic.” Those annoy the hell out of me. I’m reading books because I like reading books, the same way I like video games, and it can be a vice pulling me away from things I need to do. It’s masturbatory. It can cut me off from contact with real living humans, because I’m more involved with this other stuff that isn’t necessarily good for you. Once you accept that, you can have fun with it. This is not nearly as pious, and nonetheless strives to be a very good book by its own standards.

Writers are always beset by peers who are doing really, really well because they’re so good at the Internet.

So no, I don’t shut out the world for the sake of focus, but it’s still crucial to maintain a private identity, where you can hold opinions and be boring and unattractive. Writers are always beset by peers who are doing really, really well because they’re so good at the Internet. Their Twitter follows are five-figured, their Instagram game is great, everything they do is relevant, everything they discuss is an active topic of conversation or hits on some sort of political sensibility that everybody has an opinion about. I’ve always joked that if I started a literary movement it would be called Post-Relevance. Which you’d think would conflict with writing about twenty-somethings in a contemporary setting. But I worked pretty hard to make it stand on merits other than timeliness.

DB: It sounds a bit like you’re playing reverse psychology with yourself.

So you need to be critical, but also leave yourself room to be dumb in ways that are important to you.

TT: Exactly. And that contrarianism just is my default mode for life. At one point or another, I internalized this sophomoric idea that to be clever is to be counterintuitive. But when you settle into that identity a little bit more, you stop trying to push and fight against everyone else, and stop trying to just be publicly unacceptable, and instead be critical. Having a critical mindset, accepting nothing at face value, is the thirty-something version of that. Eventually you can end up becoming a horrible, syphilitic curmudgeon, and go off the deep end about one thing or another while calling it criticism or skepticism or whatever. So you need to be critical, but also leave yourself room to be dumb in ways that are important to you. Be dumb when it comes to enjoying things that are properly blast-shielded from your values or sensibilities. Go ahead and watch reality TV if it’s gonna make your hands stop shaking.

DB: Did you set out to write about Millennials?

TT: I instinctively recoil at presuming to speak for whole categories of people that I’ve never met and don’t know anything about. Girls was embroiled in this. The biggest mistake they made was calling the show Girls — one of the writers joked about calling it the Entitled Lena Dunham Project, and that would’ve been perfect. This is why they came in for so much criticism from people of color, who said, “You called your show Girls, and then you make a show with only white people.” Insinuating an ambition to speak for an entire category of identity. They tried to head it off in the first season when Hannah says she could be a voice of a generation. She’s trying to parochialize her own experience in anticipation of the criticism that she’s overreaching.

In the same way, if someone asks me if I’m writing about my generation, I go, “Yuck.” It’s like trying to write the Great American Novel. What kind of arrogance makes you want to speak for other categories of people and co-opt their experience, you know? That’s just vanity. That’s just you wanting to own everybody. It’s not to say it can’t be done, just that you shouldn’t pretend you’re doing anything but guessing. This is why Linda rails against the presumption of male writers with their female characters. I wanted to expose my limitations.

I’m writing about privileged mostly white people in San Francisco, because those are the people I knew. I grew up in a white town, I went to a white school, I went to another white school, and then I went to Stanford, which is not all-white, but is extremely moneyed, which in America amounts to nearly the same thing. And then I go to San Francisco, which has always been culturally diverse, but when I showed up on the scene, I arrived with these Mongol hordes of tech and finance people who followed the money.

DB: Tell me about creating Will as a character.

TT: I started by making a note that said, Okay, Will’s a tech guy who’s codependent on his girlfriend, and she’s paralyzed. At that point, I hadn’t even admitted he was Asian yet.

DB: I like how you say you hadn’t “admitted” it.

TT: Yeah, I was skirting around a lot of things. I was following this imperative of writing outside your own experience. What greater project could there be than empathy in fiction? But I realized later that this isn’t actually a value in itself — that you just have to do what’s good for whatever you’re working on.

…eventually I just had to cave and say, no, everything that gives context to his specific kind of resentment and indignation is that he’s an Asian guy.

And so whenever I used to write a character, I always had to alienate them from me in some way, so that I could reach out across and imagine my way into — basically bullshit my way into them. With Will, I started off by saying, well, he’ll be a tech guy with some of the same insecurities as me, but he’s gonna be white, there’ll be this safe buffer between us. And eventually I just had to cave and say, no, everything that gives context to his specific kind of resentment and indignation is that he’s an Asian guy. And that was the hardest thing.

DB: Why was it so important for you to barricade yourself from the character?

TT: One of the exciting possibilities of fiction is that you don’t always have to be you, something that for me feels oppressive most of the time. It’s a valid reason to write fiction — I admire people who do it well. But when this becomes fiction’s universally agreed-upon telos, and when people get criticized as self-absorbed and narcissistic for writing characters similar to themselves, it becomes a harmful dogmatic constraint. It was important for me before because I thought that’s just what talented writers did. And ultimately I realized that this kind of writing is far more like doing an impression. No one actually thinks you’re that person, but wow, it’s neat how you uncannily evoke them in this brief way. No matter how much you call yourself a writer or how much praise you get, you have to come to terms with the limit of knowing another person, which is absolute. And the value of writing about you or somebody else is — it’s value-neutral, really.

People who disagree with me — and they do all the time — say, “Well, then what about the less fortunate? Why is it not valuable to give them a voice?” I’m like, Why don’t you let them have their own fucking voice? Instead of waving a banner around about giving a voice to the voiceless, why don’t you work to create the circumstances where everyone can speak for themselves? Because you can’t do it with your fiction, right? Oh well, too bad — it’s a political issue, not a literary one.

There is a department of the literary world that values what is basically atrocity porn…

That’s why it annoys me when people get praised merely for attempting this project, not even for carrying it off very well. There is a department of the literary world that values what is basically atrocity porn, that think the more you can render the exquisite suffering of somebody who’s much worse off than you, the more laudable and legitimate your project is.

When you loosen yourself from this, then you can have fun making fun of yourself or destroying yourself in a way, because who would know how to do that better than you? The process isn’t all that different from writing about others, actually. At first you might assume you know all about yourself. But the further you go, the more you realize, no, I actually don’t know what I think about a whole lot of things. It’s only now that I’m writing from my own perspective that I’m even challenged to confront them. So in a way you’re estranging yourself. You are approaching yourself as another person until you can incorporate those ideas into your personality.

DB: There’s still plenty to explore.

TT: Right, exactly. And the more you write them, the more you end up abstracting them away from yourself. Actually, abstract is the wrong word — you concretize them away from yourself.

Once I had my roommate email me part of my book so I could work on it at my office. And he says, “Hey, sorry, man, I saw your book notes open, I closed it, but I did see that at the top it said, “Will = me — writing + girlfriend.” [Laughs.] It was a simple place to start from, a minor tweak. But then, as circumstances develop, the character develops further apart from me, until you see him in the very unhappy state he’s in by the end of the book.

This kind of reminds me of a hypocritical quote from Heath Ledger. He was nominated for an Oscar for playing the Joker, and he lost out to Phillip Seymour Hoffman playing Capote. And he says, “I thought this was an award for best acting, not most acting.” Hoffman played a character who’s very mannered and different from himself, and he gets awarded an Oscar. Of course, Heath Ledger played the Joker. But the point is well-taken, that people think that more talent and more artifice goes into acting as another than acting as yourself. It’s wrong.