Lit Mags

Human Events

by Stephen O’Connor, recommended by Electric Literature

EDITOR’S NOTE by Benjamin Samuel

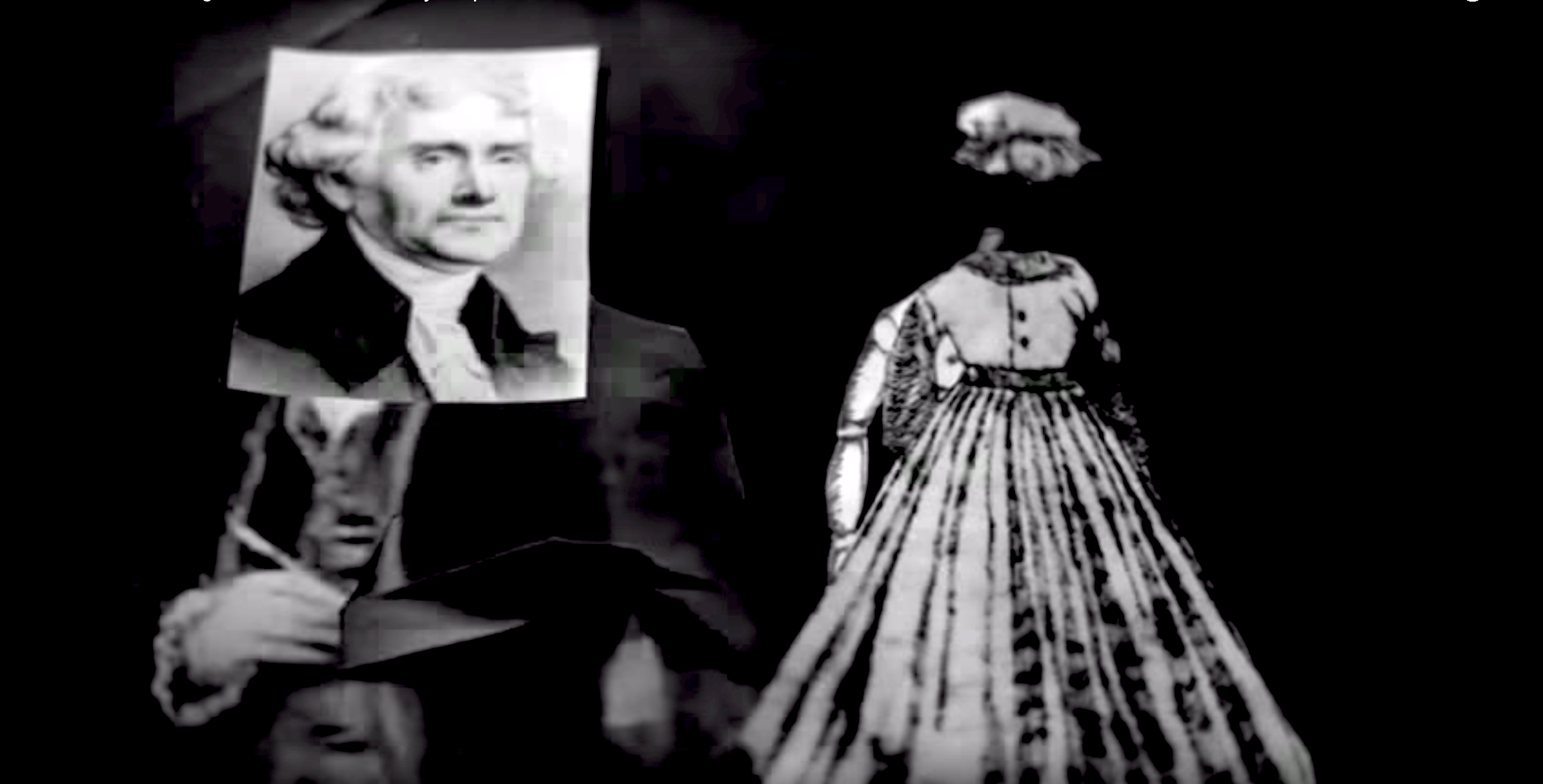

Full disclosure, this story could be classified as historical fiction. Yes, “Human Events” focuses on the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, but a story is always more than its characters. And if you’re the type to reflexively turn away from genre simply because it’s genre, you should know that this story is also experimental, metaphysical, deeply unsettling, and important.

Here, with exquisite language, Stephen O’Connor presents a fractured historical figure: a founding father who was a slave owner, a loving husband, and a rapist. The patronage of Hemings’ children was officially confirmed by DNA testing, hundreds of years after Jefferson and his family claimed the relationship was a moral and physical impossibility. In “Human Events” O’Connor shows us what that relationship may have been like, and explores how, as a nation enlightened by new revelations of who Jefferson was, we can still look upon him with “moments of indifference, or forgiveness, or even of admiration.” This story feels historically authentic and thoroughly researched, but it is its unfaltering emotional accuracy — the passion and violation and remorse — that astounds.

The relationship begins when Jefferson brings Hemings to watch a hot air balloon take flight. As they witness this seemingly impossible feat, Hemings is frozen by the thought that “What is happening makes no sense”: Thomas Jefferson is holding her hand. We are later taken from this scene of near-fantasy to the sinister reality of a powerful man entering a powerless woman’s bedroom at night. Despite moments of levity and courtship throughout the story, their relationship is haunted by refrains of ownership, rape, and remorse — even into the afterlife.

This is fiction, however, and neither a defense or an indictment. After all, Thomas Jefferson is dead and “nothing he does matters anymore.” Rather, “Human Events” resurrects a relationship that was buried even while it existed, and challenges us to question what we know about the past and ourselves. O’Connor shows us that, in reality, our emotions are flawed. Our admiration and our hatred leave us vulnerable to betrayal — or as O’Connor puts it, “our tendency to think of love as life’s greatest blessing is, alas, little more than sentimentality.” With a few words, some stains of ink — or, in this case, a certain arrangement of pixels — O’Connor complicates our nation’s past, who we thought we were and who we never thought we’d become.

Benjamin Samuel

Co-Editor, Electric Literature

Human Events

Stephen O’Connor

Share article

In some ways, Thomas Jefferson finds death more appealing than life. Nothing he does matters anymore, and so he is able to lose himself more completely in the moment. Now he is lost in the emerald translucency of locust leaves in dawn light. Now in a cloud of indigo butterflies fluttering over meadow grass. And now his heart is broken by the contest between joy and despair in every note of birdsong. Birds have three springs inside their heads, and seven cogs, and are not actually capable of choice, and yet, all day, every day, they sing of joy’s inability to outlast despair. There is something in this that Thomas Jefferson finds unspeakably beautiful.

Thomas Jefferson is holding a candle in the corridor outside Sally Hemings’s room. “I’m sorry,” he says. “Might I come in?” He goes into the room and the corridor is dark. Nothing can be seen. But his words are audible through the door: “My sweet girl!… So lovely… I will make it good… I will be gentle. You will see… Gentle… I will make it good… Good…”

Sally Hemings first comes to Thomas Jefferson in a dream. She is sitting at his desk, writing with one of his quills. The scratching of the quill’s inked tip across the paper makes a sort of thunder in his dream. Periodically, when the tip dries out and a squeaking comes into the thunder, Sally Hemings lifts the pen to her lips and dampens it with quick dart of her tongue. Only when the thunder is infiltrated by squeaks a second time, does she dab the tip of the quill into the ink, and tap it twice on the rim of a star-shaped inkwell. The result of this practice — an effort at economy, Thomas Jefferson can only imagine — is that the right corner of her mouth is surrounded by a corona of saliva-slick black, and that a trail of black descends to the edge of her chin, where a droplet trembles without ever falling.

Sally Hemings is fourteen years old and has come from Virginia to care for Thomas Jefferson’s daughters, Patsy and Polly. She has only been in Paris for two days, and Thomas Jefferson almost doesn’t see her as he passes through the upstairs parlor, partly because it is five-thirty in the morning, an hour at which no one else is normally awake, but mainly because she is so silent and still, a streak of darker gray before the gray of the window. She is leaning her forehead against the wobbly, bubbled glass, looking out onto the rainy courtyard, clutching the fingers of one hand in the near-fist of the other. At the sound of his shoe scuffing to a stop just outside the door, she becomes a burst of flutter and flight, like a ruffed grouse startled from a hedge. “I’m sorry!” she cries. “I’m sorry! I just — ” She disappears down the servants’ staircase so rapidly that if she ever finishes her sentence, Thomas Jefferson hears not a syllable.

It is the voice that stops Thomas Jefferson in the dark hallway outside the kitchen. “Juh voo dray sal-ly.”

“Non, non, non,” says Clotilde, the housekeeper. “Encore: Je voudrais celui.”

“Juh voo dray sil-ly,” says Sally Hemings.

When Thomas Jefferson hears that voice he remembers Martha on the veranda at the Forest. She was still wearing black, Bathurst Skelton only nine months dead, but already she was nothing like a widow. “In three weeks time,” Thomas Jefferson told her, “you must send me a letter consisting of one word, ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ and I will send you a letter consisting of only of one of those same words.”

It was then that Martha laughed, and, fifteen years later, in the dark hallway, Thomas Jefferson hears that laugh again.

“But what if we each write a different word?” Martha said. “That’s the beauty of it!” said Thomas Jefferson. “When ‘no’ and ‘yes’ are read together, they spell ‘noyes,’ and noise is not an adequate answer, so we will have to try again until we get it right.” They were talking about whether, when he returned from Monticello, they would perform a duet — he on violin, she on piano; a prospect that terrified them both — but as she laughed, Thomas Jefferson understood that she had, in fact, agreed to marry him, although she would never have admitted this, not even to herself. “Mr. Jefferson,” she said, “I had not realized you could be so silly!” And she laughed again.

“Juh voo dray sil-ly,” says Sally Hemings.

“Non,” says Clotilde. “Je… je… Répète: je… je… Et: ce… ce… celui.”

“Zhuh… zhuh,” says Sally Hemings. “Zhuh voo dray suh-ly.”

That voice on the soft air of an evening in June so many years ago. Martha was so happy when she laughed, and so was he. It was as if happiness were something they had discovered together, something no one else in all the history of humankind had ever experienced, their secret, their gift to each other.

And now, that voice again. In the dark hallway. From the throat of a fourteen-year-old servant girl — Martha’s half-sister. That voice of silk and sand. Thomas Jefferson stops mid-step, and for a moment he cannot move, he cannot even breathe.

“Mieux, “ says Clotilde. “Mieux, mais pas correct, ma jolie idiot!”

Sally Hemings laughs and laughs.

In Thomas Jefferson’s dream, Sally Hemings is wearing only a white cotton shift, torn at the front, and revealing an expanse of radiant skin. She does not notice Thomas Jefferson as she writes. He wants to talk to her, approach her, but is unable to move. And yet, at the same time, he has risen into the air, and it seems to him that he has drawn nearer to Sally Hemings, although that may only be a result of his altered perspective.

The lamp on his desk has not been lit. The even, sand-yellow glow filling the entire room emanates, Thomas Jefferson realizes, from Sally Hemings’s resplendent face, from the expanse of her exposed breast, and even from those parts beneath her clothing, beneath the desk and otherwise hidden from view.

And now Thomas Jefferson can actually see what she is writing — but it is not writing at all; it is a savage assault of senseless scratches, blots, crossings-out, jabs, loops, squiggles, splashes, gashes, senile quaverings, lightning bolts, comets, eruptions, bullet holes and crevasses, running in all directions, superimposed, without any regard for horizontality, order, or even the paper’s edge.

After a while, Thomas Jefferson realizes that she is compiling notes toward an invention — an iron machine, powered by steam, that moves along an iron road and makes an unending hawk-screech, so terrifically loud that anyone hearing it would be instantly struck deaf. “Why would you want to make such a thing?” Thomas Jefferson is finally able to ask. Sally Hemings fixes him in a gaze of contempt. She cannot speak. She is mute. And her muteness so terrifies him that his legs jerk and arms shoot out, he cries aloud and finds himself awake in the cold, blue night, alone in his bed.

“… Gentle… I will make it good… Good…”

Thomas Jefferson is forty-six and Sally Hemings is sixteen. They are in Paris and it is late April, 1789.

“Madamoiselle Sally,” Thomas Jefferson says, “j’ai une petite surprise.”

“Oui?” Sally Hemings asks. “Est-ce que Patsy et Polly — “

Thomas Jefferson cuts her off: “Non, non, pas comme ça!”

“Quoi donc?”

“Un miracle!” he says.

“Ah, non!” says Sally Hemings, crinkling the bridge of her nose. The last “miracle” Thomas Jefferson presented to her was a lump of cheese that looked and smelled exactly like clotted matter scraped out from under a toenail.

Thomas Jefferson laughs. “Non, non! Nothing like that!” He laughs again, remembering how, during the instant she held that morsel of cheese in her mouth, he could see the white all the way around her hazel irises, and how, in the next instant, she spat the cheese onto Madam d’Arnault’s Persian rug and ran straight out onto the street. “Je te promets,” he says. “This will be like nothing you have ever experienced. A real miracle — you’ll see!” Thomas Jefferson observes suspicion doing battle with curiosity on Sally Hemings’s forehead and lips. “Come along,” he says. “Allons y!” And then he tells her, “Perhaps you should put on that yellow gown. And your embroidered cape. You will want to look your best.”

After an interval of muddy streets, and a brisk trot along a country road, during which Sally Hemings sits beside the driver, she finds herself in a mown field, at the center of which a crowd surrounds a bonfire and something like a gigantic purse — blue and red silk, frilled on the seams — is stretched out on the grass.

At first Sally Hemings cannot imagine why Thomas Jefferson asked her to wear her finest clothes to this rural ceremony (or whatever it might be), but then she notices that the crowd consists almost entirely of Parisian high society. The Princess Lubomirsky is there. And Monsieur and Madam de Corny. And Baron Clemenceau, with his crooked mustache. What on earth could draw such men and women to some peasant’s hacked pasture? And why is it that they are all chattering with such excitement, and staring at the activities of the men around the bonfire?

The mouth of the purse stretched out on the grass is held open by a six-foot-high wicker ring that two men hold on edge, while four others blow smoke into it by waving sailcloth fans. There seem to be other men inside the purse, because a sort of dome — mounted on poles, perhaps — keeps rising and falling within its far end. As the men blowing the smoke grow tired, they are replaced by others; while still more men keep heaping wood on the fire. The dome, rising and falling inside the purse, grows larger and looms higher with every new waft of smoke.

“Now look!” says Thomas Jefferson, leaning so close his lips practically touch her ear. “It is about to happen. You will see. A true miracle!”

But Sally Hemings cannot pay attention. She is trying to figure out if Thomas Jefferson’s lips might, in fact, have touched her ear. And she is still feeling the low burr of his voice inside her head. Her heart is pounding and she is covered in sweat. She looks around to see if anyone is staring at her, but all eyes are on the enormous purse.

“It is happening!” Thomas Jefferson says, standing tall again, entirely removed from the vicinity of her ear. “Watch! A man is going to fly!”

Sally Hemings does not believe him, of course. A man flying? Impossible!

But then, with a sound like the earth itself heaving a sigh, the giant purse lifts off the flattened grass and, guided by shouting men pulling ropes and pushing with poles, it swings, bottom up, directly over the fire, some ten yards above the flame-tips, where it is held in place by four strong ropes tied to four stakes. Sally Hemings waits for the men inside the purse to tumble into the fire, and when they never appear, she imagines them hovering within the purse’s shadowy interior, just as the purse is hovering in the air.

There is a platform beside the fire, and on top of the platform: a wicker canoe connected by slender lines to the inverted purse. A young man, also wearing blue, yellow and red silk, climbs a ladder, and steps gingerly into the canoe. His curly, chestnut brown hair falls well past his shoulders.

Thomas Jefferson touches his forehead to Sally Hemings’s temple. His breaths puff against her ear, and his voice is low. “That is le comte de Toytot.”

The man sitting in the canoe is making a speech, but Sally Hemings’s French has vanished. She understands nothing — except that he is about to fly.

And then, in a single instant, four men with swords cut the four ropes, and the inverted purse lifts from the earth with the fluid grace of a wave at sea. As the wicker canoe swings off the platform, and also begins to rise, the foolish young count with the long brown hair laughs — as if he has not committed an abomination, and is not about to die, and has never, in fact, been happier in his life.

“What is he doing!” Sally Hemings cries, grabbing Thomas Jefferson’s sleeve.

“Nothing.” Thomas Jefferson smiles. “Just this: He is going to fly like a bird. And then, when the air inside the ballon cools, he will sink slowly to the earth. It is all safe. All under control.”

This time she believes Thomas Jefferson, not only because he knows more than any man on earth, but because she can see that what he is saying is true. The man and the ballon continue to rise with a breathtaking grace, but sideways, drifting with the breeze.

Only once Sally Hemings feels a hollowness come into her throat, and the whole of her body going cold does she realize that Thomas Jefferson has taken hold of her hand, the one with which she had grabbed his sleeve. The hollowness in her throat expands and becomes a sort of dizziness. What is happening makes no sense. Why would Thomas Jefferson do such a thing? Again and again she wonders if the pressure she feels on her fingers could possibly be the pressure of Thomas Jefferson’s hand, and again and again she is unable to accept the obvious fact.

But then her hand is empty, and Thomas Jefferson is running. The entire crowd is running. She can still feel the pressure of his hand, and the sweat their hands made together, but now Thomas Jefferson is far enough away that she would have to shout for him to hear. She lifts the skirt of her yellow gown, and runs across the field after him, along with the rest of the crowd, until finally, at the edge of a wood, they must all stop, while the ballon — now higher than several houses piled one atop the other — glides silently over the trees.

Over the trees! A man flying over the trees!

Now Thomas Jefferson is next to her again. “Should I ask Monsieur le comte to take us with him next time?” he says, his lips once again beside her ear. “Would you like to fly with le comte de Toytot?”

“Oh no!” says Sally Hemings. “I’d be too afraid!” Then, almost immediately, she thinks: Yes! I do want to fly with Monsieur le comte! I do! I do! Oh please ask him! Please take me with you!

But these words never pass her lips.

Thomas Jefferson is an artist of silence. Into the midst of whinnies, susurrant poplars, catbird shrieks, jingling harnesses, cicada drones, coughs, field chants, foot thumps, hawk cries and thunder rumbles, he introduces silences — some of them lasting half a breath, others as vast and enduring as the silence between stars. Silence is a form of freedom. In silence ought need never be contaminated by is, and is is, simultaneously, not at all. Silence is our agreement that the world is more than we can bear. When the silent people in the silent room close their eyes, they are utterly alone. A solitary word in the midst of silence has no meaning.

“… I will make it good… Good…”

“You cannot pretend that you do not share my feelings,” says Thomas Jefferson.

There are two bottles of wine on the table, one empty, the other not quite. There are also two glasses. Thomas Jefferson has just finished his. Sally Hemings’s is almost full. This is her third glass. He has been counting. Or maybe her fourth.

“I can see it in your eyes,” he adds.

Sally Hemings is not, in fact, looking at Thomas Jefferson. She is looking at her hands, her right thumb massaging repeatedly the center of her left palm.

“I could see it,” says Thomas Jefferson, “when you took my hand out on the field. Do you remember? Just as le comte de Toytot was borne into the air?”

Thomas Jefferson wants her to look at him again. He reaches across the table and touches her shoulder with his fingertips.

Now she is looking into his eyes, her own eyes tremulous in the flickering firelight.

There is a plunging in Thomas Jefferson’s breast that is equally pain and joy. “My God!” he says. “You are so beautiful.”

Sally Hemings’s gaze sinks once again to her lap. “No.”

“Yes!” Thomas Jefferson wants to draw the back of his index finger softly along her cheek, but instead he reaches for the bottle. “You are a vision!” He refills his glass, then swirls the dark fluid once.

“No,” she says, still not looking at him. “I didn’t take your hand.” At the word “didn’t,” her head lifts and she looks him straight in the eye. Her gaze is firm, but he can see that she is trembling. He worries that in moment she will begin to cry.

“I’m sorry.” He takes a deep sip form his glass. “I am sorry. I have been presumptuous.”

“No,” she says. “You have — ”

He cuts her off: “I am sorry.” There is anger in his final word, and he is ashamed of his anger. Now he is the one looking down. “I have allowed myself to be blinded by feeling.”

“No.”

“Please,” he insists. “I am sorry.” This time he speaks the word with a suitable tenderness. “You are a beautiful young woman, Sally, but that does not give me the right — ”

He stops speaking when he sees her smile. Again that plunge of joy and pain. He wants to pull her into his arms, but does nothing. He takes another deep sip his glass. She is still smiling, a private smile, one that makes him wonder if he might hope.

“Thank you,” she says. “I had a lovely day. I will never forget it. C’était un vrai miracle de voir un homme volant dans le ciel.”

“Yes,” says Thomas Jefferson. “Wonderful. Vraiment.” She has stopped smiling. He sees the trouble in his own face reflected in hers. “Perhaps you had better leave me alone, Sally. I have work to do.”

The smile returns weakly, then vanishes as she pushes her chair back from the table and stands.

“Certainly,” she says, and as she backs away from the table: “Sorry.”

Then she is gone.

Alone in the warm, illuminated room, Thomas Jefferson finishes his glass and pours another.

Not hours before Martha died, her voice hardly above a whisper, she drew Thomas Jefferson’s attention to a strange beetle with a tiger-striped cowl that was crawling across her bedclothes: “Look, Tom. I’ve lived all this time, and yet every day I see an insect unlike any I have ever seen before.” He told her that as soon as he had a moment, he would see if he could find its name in a cyclopedia of insects that he had recently acquired. That moment never came. Not long after Thomas Jefferson took the beetle between his thumb and forefinger and deposited it on the window ledge, Martha closed her eyes and her soap white skin went ash gray. Soon her breathing became irregular, with the gaps between breaths growing longer and longer, until finally, just before sunset, she took the three enormous breaths, each followed by an impossibly long silence, the last of which never ended.

First Sally Hemings sees a golden shimmer along the top of her door, and then she hears the whisper of a leather sole on wood. A knock. So light that she is able to pretend to herself she hasn’t heard it. Then another knock. She has been lying flat on her back for more than an hour, unable to sleep. For much of that time, she felt herself listing sideways in the darkness, as if her bed were a boat caught by the current of a mirror-smooth river. It was the wine. She has never drunk so much wine. She feels it still, as a wisp of nausea at the base of her throat. And the listing. That is there too.

But it isn’t only the wine.

No sooner did she stretch out under her covers than the moments of her day began to repeat inside her head: le compt de Toytot waving happily as he drifted over the trees, the low vibration of Thomas Jefferson’s voice filling her ear, the feather touches of his lips, his sweating hand — but also what he said while she was drinking her wine: “You are so beautiful. You know that, Sally, don’t you?” His nose was red, his eyes and mouth drooping, as if his face were melting in the heat of the fire. “Beautiful,” he said. Over and over. At first, as she heard these words, the hot thickness in her throat felt something like embarrassment, but then it hardened into a sense of something wrong — maybe something very wrong. “Beautiful,” he said. “You cannot pretend…”

Another knock.

“Sally?”

It is him.

He knocks again. “I’m sorry to disturb you.”

It is raining outside. She hears the echoey clatter of water in the gutter pipes, and the gust-driven rain like sand flung against the windows.

“Sally?”

“One second,” she says.

She is already standing, her bare feet on the cold floor. She doesn’t know what to do. The cold is creeping up her body inside her shift. She wants to find her dressing gown, but she doesn’t know where she left it. There is no light in her room. She can’t see anything at all except the wavering glow around the door.

“I’m sorry,” says Thomas Jefferson.

Maybe she threw her dressing gown across the chair beside her chest of drawers. As she takes a step in that direction, her middle toes slam against the corner of her night table. A flare of pain illuminates the blackness. The enamel chamber pot clanks but doesn’t spill.

“Sally?”

“One second,” she groans, balancing on one foot, clutching her throbbing toes with both hands.

“Are you all right?”

“I’m fine.”

She has found the chair — nothing on it but a single stocking. Now her knee collides with the chest of drawers, but only enough to rattle the glass knobs. No pain. But somehow the fact that she keeps knocking into things leaves her feeling helpless and faint. How can this be happening? Her throat has gone dry, her teeth are chattering, and Thomas Jefferson is so close that she can hear him breathe.

“I’d just like a word with you,” he says. “One word.”

She steps toward the wavering golden outline of the door. There is something soft under her foot. Her yellow gown. She simply threw it onto the floor in her haste to bury herself under her covers. She picks it up, puts it over her head and slides her hands down the sleeves. Now she is standing just inside the door, the back of her gown unbuttoned to her shoulder blades.

“It’s late,” she says.

“I know. It won’t take a minute.”

The door is not locked. He could have opened it and come in any time. Maybe everything she’s been thinking is foolish. Maybe there’s nothing at all to fear.

She lifts the latch and pulls the door inward, peering around the edge, keeping her body out of sight and pressed flat against the paneled wood.

“Oh Sally!” Thomas Jefferson gasps softly, and then gives her a happy smile. His hair is a mess, as if he has been gripping it in his closed fists. His eyes look gelatinous in the glow of his candle. Even as his feet remain fixed to the floor, his head and shoulders rock as if he is on a ship at sea.

“Might I come in?”

For reasons that Sally Hemings will never be able to comprehend, she backs away from the door as soon as he asks this question, and then she runs to her bed — which she realizes instantly is exactly the wrong thing to do.

But it is too late. Thomas Jefferson is in the room and he has closed the door behind him. He hurries toward where she stands just beside her bed, puts the candle on the night table and takes her hand as he sits down.

“My sweet girl!” he says.

He is holding her hand in both of his. Sally Hemings does not resist. She is paralyzed, and no longer feels contained within her body. Rather, she seems to be hovering a few feet above her own head, watching what is happening, and not particularly caring, feeling nothing but a hurtling sort of numbness.

Thomas Jefferson squeezes her hand gently. “I just had to see you,” he says. “Do you understand? I couldn’t stop thinking about you.” He smiles crookedly. “I think you do understand. You are, of course, most innocent and modest, but…” He looks straight into her eyes. “…I think you do.”

He stands and moves toward her, looming so large in the darkness that he seems twice her size. Now his mouth is on hers. She feels the prickliness of his lip and chin. His lip slips between hers, and then his tongue. “Oh, Sally!” he gasps. “Oh, Sally! You are so lovely! So utterly lovely!”

Now he is kissing her neck, her throat. His hands are running up and down her body, touching her in places, front and back, where no one has ever touched her before. The feeling of his fingers on her body fills her with a searing loathsomeness. She wants to slap his hands away. She wants to shout, “Leave me alone!” She wants to bite his tongue. But she does none of these things. Looking down from above, she sees herself as a limp ragdoll. If he weren’t holding her up, she would fall to the ground.

“I will make it good,” he says between kisses. “I will be gentle. You will see. Gentle. I will make it good. Good.”

And now he has lifted both her gown and her shift over her head. And now he lays her naked body on the bed. He is kissing her breasts, her belly, that part of her body down below. He is making the husky grunts and ripping sighs of animals.

All at once he pulls away. He is standing beside the bed, tearing at the buttons on his breeches. She knows what is going to happen. It cannot be possible. But that makes no difference. It is happening. It is inevitable. And there it is. Like a club sticking up out of him. Like a skinned fish. Like an enormous mushroom that is practically all stem. She never imagined it could be so repulsive.

But now something else has happened. Her entire body has gone rigid. He tries to move her legs apart, and he can’t. He cannot move her hands from her side.

He laughs softly. “Sweet girl! Don’t worry. I understand. I will be gentle. You will see. I promise. I will make it good.” He is talking between kisses. And he is kissing his way up her body. She feels his blunt, hot thing bump just above her knee, then press into her thigh, lightly at first, then harder.

When his mouth reaches hers, she keeps her lips clamped shut. She is shivering. Her whole body is icy in the icy air, and she can’t stop the shivering.

He pulls back his head. “Sally?” He starts to smile, but then his smile fades.

She makes a small shriek, like a rabbit in the jaws of a dog, and shakes her head once, hard. She cannot speak.

“Are you all right?” he says.

Again she shakes her head.

For a long moment he only looks at her, his disconcertion resolving slowly into a deep exhaustion. “Oh God!” he says. “Oh God! How could I be such a fool?” He turns away from her. Sitting on the edge of the bed, he puts his elbows on his knees and his forehead into his hands, clawing at his hair. “I’m sorry! I am so sorry! Oh, God.” He stands and pulls his breeches up from around his ankles. “I can’t believe I… I can’t believe… What a fool… Unforgivable….”

Then he is gone. The door has closed behind him.

His candle is still on her night table. The flame drops and flutters as a gust seeps around the window casing.

Outside her door: an abrupt, hollow thundering. He has stumbled on the stairs. Quiet. An exhalation. He cannot see. Unsteady foot thumps quieten as they recede. He must make his way in total blackness. By touch alone.

True hate is effortless. It is called into being spontaneously, inevitably, by the hateful object. When the object is not purely hateful, however, hate requires effort, and if such hate regards the complexly hateful object as if it were purely hateful, then the hate, itself, is not pure. The world abhors purity. The world abhors most things that are designated true. The world abhors perfection.

And because we ourselves cannot be perfect, there are moments when the effort of hating the hateful thing is more than we can manage — moments of indifference, or forgiveness, or even of admiration. And if the hateful thing is sufficiently deserving of our hatred, those moments in which we are not sufficiently hate-filled can inspire us to hate ourselves, just a little, or sometimes a great deal. This is because hate is so intertwined with morality as to make the two almost indistinguishable.

Love, too, is intertwined with morality, but far less intimately. We are more than capable of loving someone without thinking him or her morally perfect. But when we hate someone, it is very hard for us not to think of that person as evil — which is precisely why those moments when we find ourselves indifferent to, or forgiving, or admiring a hateful and therefore evil person can leave us feeling that we too are evil and deserve to be hated.

It is a well-known fact that hate not unambiguously anchored in moral condemnation tends to degenerate over time into gentler emotions, or into no emotion at all. And, it is also true that hate anchored less on moral condemnation than on simple fury can spontaneously flip over into love, that most capacious of emotions, that emotion which can not only thrive in the presence of hate, but be intensified by it. And for this reason our tendency to think of love as life’s greatest blessing is, alas, little more than sentimentality.

Sally Hemings is thirty-one and the man inside her is history itself. He shudders as he works. The skin between his Adam’s apple and chin is as puckery as the skin of his scrotum. When she grips his arm above the elbow, she can feel the straining of his sinews as a steady vibration, like a twang passing through a guitar string. Those sounds escaping his throat: They are the noises of an infant at its mother’s breast. Yet he cannot be resisted. Sally Hemings has scant learning, but she knows that history has the habit of humility. Death entered the breast of little Lucy through a single cough. A solitary ember popped from bed-warmer to rug, and Chandler Hill became an acre of ash and two blackened chimneys. This man himself spent a night emptying wine bottles with friends and then ten thousand people died. And so, fifteen years ago, when he came into her room and left with his head in his hands, she understood that he was only dressing fate in the clothing of possibility, and submission in the guise of choice. But she also understood that he had stripped himself naked, that he had revealed to her and to himself that he was a man like all men, that his own name designated little more than a wish and a lie, and that the magnificence of God’s will is never transmitted to the men who enact it. And so, in that moment, she attained a sort of freedom. And so, just now, when he looked at her in that way, she answered him only with a steady gaze and a quickening of breath. And so, when he put his hand on her breast, she covered his hand with her own, closed her eyes and opened her mouth. And so, now, this moment, her ankles are locked across his back, and now she grips his upper arm and lets the rough shuddering that drives cries from his lips drive answering cries from her own.

Thomas Jefferson is not real. His lead horse leaves bloody tracks in the snow. Otherwise the world is white, particulate, hurtling, and loud. First Thomas Jefferson cannot feel his fingertips, then his feet fade away, and the outside of his right leg.

He has three glasses of cider at the post house while his horses are being changed. The hostler stamps the snow off his boots, scattering white chunks across the gray floorboards. “Everything’s ready, your Excellency.”

“No,” says Thomas Jefferson. “Don’t call me that.”

“Sorry,” says the hostler, his nose claret-red, his cheeks the unsteady red of a not-quite-ripe peach. After half a breath’s hesitation, he adds, “President Jefferson,” and lowers his head.

Thomas Jefferson is not the president either. Not anymore. He will never return to Washington. One last swallow. The tankard comes down on the hacked table-top with a satisfying bang. He thanks the hostler, and the innkeeper. The hostler follows Thomas Jefferson outside, and watches from the porch as he is taken apart by the hurtling snow. The harness clinks, the muffled thumps of eight hoofs grow ever quieter. Thomas Jefferson diminishes, grays. His body fragments. And between the fragments is a fierce gray-white. The fragments whirl away. Vanish. First one. Then another. Then another and another. Then dozens at once. Finally there is nothing left but that gray snow, which is only white snow in the shadows of the numberless flakes hurtling sideways between the earth and that clean, clear, emptiness above the clouds.

Sally Hemings is dead. The yard behind her house in Charlottesville is loud with the braying of mockingbirds. The rag and bone man’s cart clatters on the cobblestone street out front. Her children are gathered around her bed, her three sons, all upright young men, and her daughter, who has not been back to Virginia in thirteen years, and who arrived only minutes after her mother breathed her last.

Sally Hemings’s dead children are there also: the daughter taken by fever after she had learned to walk but before she could ever run; the daughter still small enough to cradle between elbow and palm, who went to sleep two days after she was born and never awoke; and the one Sally Hemings always called “la petite,” who had been conceived in Paris and who, no bigger than her fist, had come into this world on a river of blood and had been buried at Monticello in a ceramic pot.

The dead children grieve, but their grief is gentle, like a winter fog over a yellow field. The grief of her living children has turned them to stone. They do not talk. They are waiting for something to change, and nothing will ever change. The eldest is holding a violin, but he has left the bow in the front room.

Outside the window, the trees heave in a sudden wind. The sky grows dark and the mocking birds fall silent. For long moments rain is about to fall, but, after a rumble of thunder, the wind recedes and the sun returns.

Now Thomas Jefferson is also in the room, even though he too has been dead nine long years. Sally Hemings looks at him, but doesn’t say a word.

Minutes pass before he finds the strength to tell her, “I wanted you to be happy, but you were never happy.”

“I was happy,” she says.

“With me?”

“Yes,” she says. “I was happy.”

Thomas Jefferson does not believe her. He does not believe her because he himself was never happy. There were many, many times when he had pretended otherwise: the time when she had acted out the story of Cinderella with a tea cup, salt shaker and two forks, and the two of them had laughed and laughed and laughed; or the time they had spent the whole day riding, then cooled off with a swim in Johnson’s Creek, and then made love on a horse blanket spread over a bed of mint; or that afternoon when he was sitting beside her on her bed, bouncing six-week-old Beverly on his knee, and the tiny boy, seeing two huge faces looking down with rapt delight, had made the first cackly laugh of his life. Thomas Jefferson had known many such moments with Sally Hemings, and had managed to believe, every time, that he was happy, that Sally Hemings was happy, that no two people could be happier. But now he knows that, on every one of those occasions, his own happiness had been infected by fear, by his sense that what he believed was happiness could not, in fact, ever exist in this world, and that, in a moment, he would have to live in the world as it actually was: a place of unending loss and shame.

He takes the empty chair between two of their living sons, and across the bed from their daughter and their youngest son. “No,” he says. “You were never happy. There is no need to lie anymore.”

“I am not lying,” she says, but after that she can think of nothing else to say.

For a long time the silence in the room only deepens. Then a mocking bird launches into a fleet and fragmentary improvisation.

A drizzle grays the air when Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings visit the Museum of Miscegenation. They approach the columned and domed marble edifice (which Thomas Jefferson cannot help but notice is in the Palladian style) along an avenue of plane trees, all-but-invisible droplets drifting between bare branches tipped with the tiny lettuces of just-bursting buds. The drizzle coats the square cobbles like breath upon a mirror, and Sally Hemings, wearing leather-soled shoes, finds the footing so slippery she has to cling to Thomas Jefferson’s arm until they are inside the museum.

They have come unannounced, but as soon as they step through the glass doors into the cathedral-size lobby, a security guard nudges a young man in a trim black suit standing next to him, and nods in Thomas Jefferson’s direction (no one, of course, knows what Sally Hemings actually looks like). The young man immediately goes over to the information desk, picks up a telephone and dials.

Swimming pool-size banners hanging from the ceiling advertise two new shows: THE MYTH OF PURITY, and EUGENICS: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE, but Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings are interested in neither. They have come, after many second thoughts and much procrastination, to view the entire wing of the museum devoted to their thirty-eight year relationship.

The young man has put down his telephone, and seems on the verge of approaching them, so they turn their backs, and hurry across the lobby toward a considerably smaller banner:

THOMAS JEFFERSON & SALLY HEMINGS

AN IMPOSSIBLE LOVE

Just as they pass through the doorway beneath the banner, Sally Hemings looks back and sees that the young man has been joined by a gray haired, stocky woman in a magenta suit with a knee-length skirt. She has one hand on the young man’s forearm, as if holding him back. They are both staring at Sally Hemings, but neither budges nor makes any show of greeting.

The interior of the gallery is so dim that the spaces between the spotlit exhibits seem fogged with granulated pencil lead. Thomas Jefferson is already standing beside a vitrine. Sally Hemings rushes over and takes his arm again, feeling less exposed pressed against his side.

It seems that in their hurry to escape notice, they have entered the show though its exit. The vitrine into which Thomas Jefferson is looking contains his spectacles, inkwell, and shoe buckle. Sally Hemings carried these in her bag when she left Monticello, and she gave them to their son, Madison, shortly before her own death. These items look far too paltry to be arrayed on velvet under golden spotlight. But seeing them after such a long time, Sally Hemings is so weakened by sorrow that her fingertips and legs go trembly. Thomas Jefferson glances at her with a sad smile.

“I’m glad you got these,” he says. “The inkwell, especially.”

She smiles hesitantly and nods. She cannot answer. She lets go of his arm.

“I don’t recognize the buckle, though,” he says. “Are you sure it’s mine?”

“It was in the lodge. I went there the day after your funeral. It was under the chair by the bed.”

Thomas Jefferson’s smile has vanished. “I didn’t know you did that.” He gives her hand a long, firm squeeze. “Oh God, Sally.”

“Do you want to go?”

“No. That would be a waste. We’ve come all this way.”

Some of the displays are amusing — the dioramas especially. One shows Thomas Jefferson standing in front of a fireplace, playing a violin while mannequins representing his granddaughters, Ellen and Cornelia, both looking about eleven years old, whirl, elbows linked, in a merry jig. Almost everything is wrong with this exhibit. First of all, Cornelia absolutely hated dancing, in part because her actual proportions — unlike the mannequin’s — verged on the elephantine. Second of all, no one’s clothes make sense. Thomas Jefferson is wearing a braided, gold-buttoned, royal blue frock coat, which is far too formal for so humble and domestic an occasion. And his waistcoat is an absurd cardinal red, such as a tavern keeper might wear. The girls, by contrast, are in mauves and pigeon-gray, which they would have considered too dour and old-fashioned even for their grandmothers.

Most ludicrous of all are the faces of the mannequins, ostensibly based on portraits painted “from life.” Thomas Jefferson, at least, looks as if he belongs to his own family — though not any closer to himself than a second or third cousin, and the grin on his face is the sort that only accompanies intense discomfort of the lower intestine. The mannequins representing the girls both look like demented elves, neither bearing the faintest resemblance to the actual Ellen and Cornelia.

Sally Hemings is also in the scene, though her face is not visible, since she is shown watching the family merriment from a dark hallway.

In every single one of the dioramas and modern illustrations, Sally Hemings’s face is either in shadow or turned away from the viewer. This is because, as the captions to the displays repeat time and again, if any portraits of her were ever made, none has survived. She understands that the absence of her face represents the museum curator’s desire both for historical accuracy and to make a statement about her “invisibility” in Thomas Jefferson’s world, but she can’t help feel affronted that she alone, of all the people represented, is deprived of the most significant physical manifestation of identity, especially since the faces of every other member of the Jefferson family and social circle could hardly be less accurate.

She is also disturbed to see the knives, forks and spoons she remembers as shiny copper and silver looking black and withered, and the blue china plates off which she ate thousands of meals, now only partially reconstructed assemblages of variously discolored fragments. Most disturbing of all is a display of miscellaneous bits of pottery unearthed at Monticello, in which she notices two arced pieces of the jam jar in which she buried “la petite,” her miscarried first child. Thomas Jefferson passes right over this display without even noticing what it contains, and she doesn’t bother to inform him. She lingers behind as he moves on to other exhibits, however, and it is a long while before she can bring herself stand near or talk to him again.

In the end she is moved to return to his side and, finally, to take hold of his hand by the responses of the other people in the gallery — about half of whom obviously have African ancestry. The overwhelming message of the show, rendered anew in exhibit after exhibit, is that, when it came to the Africans with whom he spent almost every day of his life, Thomas Jefferson was a selfish and spitefully prejudiced hypocrite — which, indeed, he was, Sally Hemings realizes far more clearly now than she ever did at the time, though that is not all that he was. As he and she move between pools of illumination in the twilit rooms, people are constantly murmuring sourly to one another, and making comments like: “What a bastard!” Or, “I used to admire this guy!”

Thomas Jefferson gets few second glances, however, and maybe one or two stares, but no one comes up to him, no one cups a hand over his or her mouth and whispers into a neighbor’s ear while glaring at him fiercely. But as he and Sally Hemings are watching a video in which some of his writings on slavery are read aloud by an actor, a man of African descent does look directly at Thomas Jefferson, and says in a loud voice, “This country would have been a hell of a lot better if all the white people had been sent to Ohio or Canada!”

Thomas Jefferson responds to this man’s words and, indeed, to every other overt or implicit disparagement he receives that day, as he always responds to criticism: by pretending not to notice it.

As he and Sally Hemings are leaving the video, she takes his hand in both of hers, draws her cheek next to his, and says, “I hope this is not more than you can bear.”

At first he only sighs heavily without speaking. But, after a long moment, he says, “It seems that I have never….” He is silent another long moment, then shrugs and pats her hand. He doesn’t look her in the eye.

As they draw near the end — which is to say, the beginning — of the show, they come to a vitrine displaying the very gown that Sally Hemings was wearing the day they went to see le compt de Toytot fly in a hot air balloon, and that she was wearing later that night, when Thomas Jefferson entered her room.

They stand side by side in front of the vitrine, as if before an apparition, their faces tremulous with the repeated impacts of possibility and doubt. The gown, suspended in midair by nearly invisible fishing line, is the only item in the whole exhibit that seems untarnished by time, its yellow silk radiant in the spotlight, and its white underskirts as brilliant and luxurious as clouds.

After a moment, they notice a guard standing next to them. He is dark-skinned and heavy-set, and he is smiling at Sally Hemings. “Would you like to try it on?” he says.

“Is that allowed?” she asks.

The guard nods beneficently. “For you, of course.”

He pulls out a set of keys, attached to his belt by a chain, unlocks the back of the vitrine, and detaches the gown and its underskirts from the fishing line. As he hands them to Sally Hemings, he nods wordlessly toward the door of a women’s room.

She takes the gown and skirts into her arms as if they are the wasted body of a child. When she emerges from the women’s room, her expression is solemn and intent. She is barefoot, clutching her raincoat against her chest.

The guard has left the room, and, for the first time since they entered the museum, Sally Hemings and Thomas Jefferson are entirely alone. “You have to do me up,” she tells him, and turns her back. “The stays are missing. I’m sure I’ll look terrible.”

“It will be fine,” says Thomas Jefferson, as he fastens the many little buttons from just below her waist to the nape of her neck.

And, indeed, when she hands him her raincoat, and turns to face him, she seems hardly to have changed since she last wore the gown so many years ago.

She is looking into his eyes, waiting, still solemn and intent. He is afraid to speak. He is feeling so many different kinds of sorrow, but also a lightening of spirit — something very like hope.

She swallows, and parts her lips, as if to form a word. But then she clamps her mouth into a thin seam, and the skin around it goes yellow. She is still looking into his eyes, and he is looking into hers.

The guard has returned, stepping sideways through the door, glancing over his shoulder toward the room he has just left. Then he looks directly at Sally Hemings, tilting his head to one side, his brow furrowing and his lips going into the lumps and twists of someone who wants to smile. Finally, he shrugs and parts his open hands in the gesture that signifies helplessness. There are murmurs in the next room, and the whisper of shoe soles on polished wood.