news

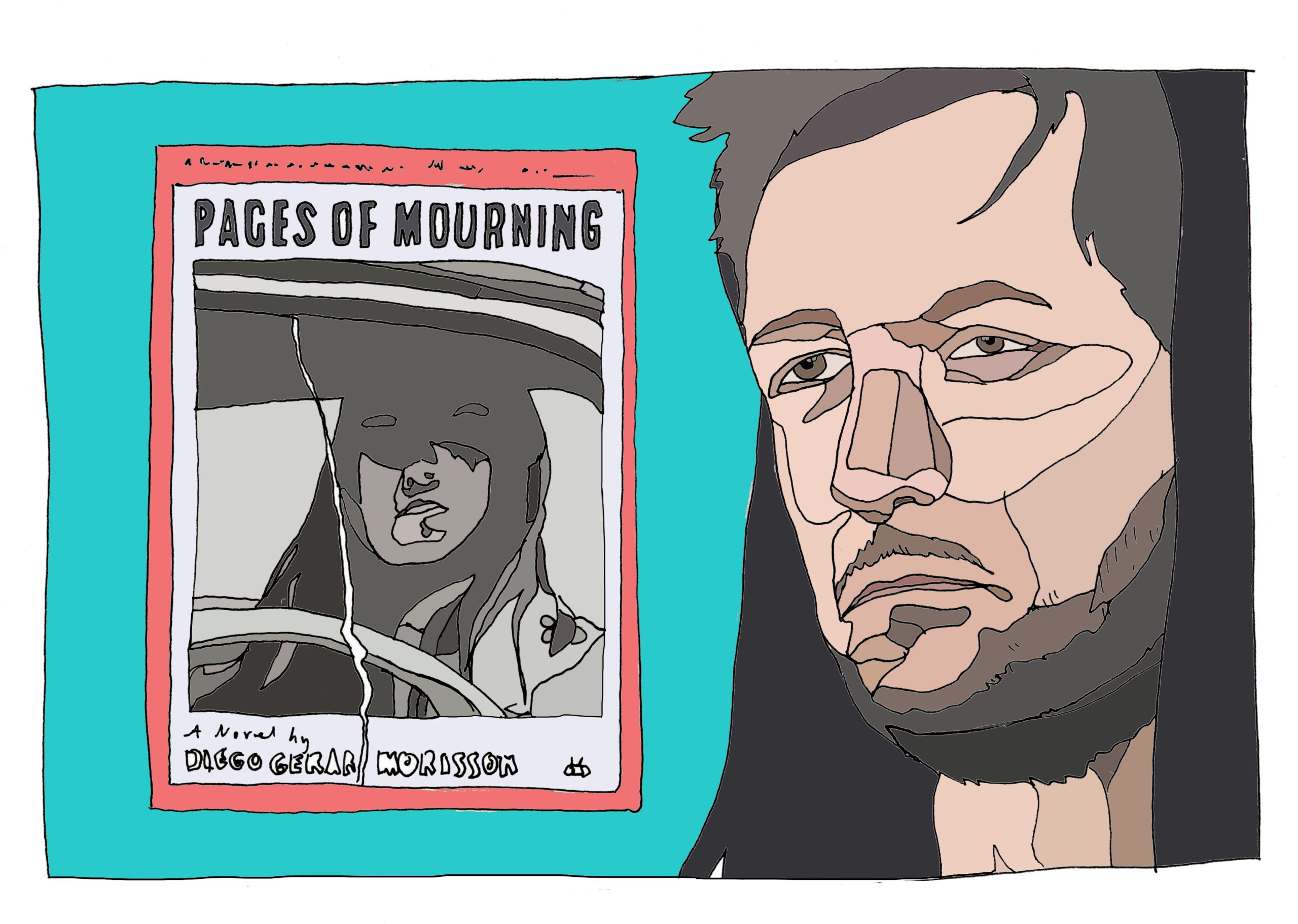

“I Didn’t Want to be a Writer, I Wanted to be Nothing”: László Krasznahorkai and James Wood at…

When I showed up at Housing Works last night, late as always, I walked into the busiest Monday night reading I’ve ever seen. Something special was waiting to happen. The bookstore had been transformed into a lecture hall, with long rows of filled seats fixed before the podium. Latecomers were pressed against the bookshelves. My friend Tiffany, who’s normally on time, was among them. “It was like this twenty minutes ago,” she said. I squeezed past the bookshelf-wallflowers, wondering what was different about this reading, until I nudged and bumped enough people to realize that Laszlo Krasznahorkai, the Hungarian novelist whose rare appearance in America had drawn this group, managed to fill Housing Works with a crowd that wasn’t depressingly homogeneous. Professor-types peaked over the mussed up hair of East Village kids as buttoned-down editorial assistants offered their seats to faded old men with canes. In the front, some guy set his iPhone on a tripod and tapped the screen to take pictures of Krasznahorkai as he spoke to critic James Wood. He probably worked for New Directions, who organized the event to celebrate the English translation of Krasznahorkai’s first novel, Satantango.

1. View from the back: László’s in there somewhere. 2. James Wood introducing and László Krasznahorkai, being introduced.

The evening began with a lengthy opening by Wood, who had introduced many American readers to Krasznahorkai in his July 2011 New Yorker profile, “Madness and Civilization.” After reading a passage from Krasznahorkai’s War & War, Wood discussed Krasznahorkai’s long, serpentine sentences, which create a “world of obstruction, as well as a channel of clarity.” He presented Krasznahorkai as a rare contemporary writer who is not embarrassed by the metaphysical, and who glimpses at “what is not disclosed by language.” Krasznahorkai, dressed entirely in black, sat silently, poured Wood a glass of water, accepted his praise.

Wood followed his introduction with an interview. When asked about the length of his sentences, the writer said that he distrusted short sentences because people speak with commas, not periods. “The dot belongs to God,” Krasznahorkai explained, “not the human; and perhaps God will make the last dot.” The audience applauded.

Discussing his beginnings as a writer, Krasznahorkai explained that he only wanted to write a single book. “I didn’t want to be a writer,” he said. “I wanted to be absolutely nothing.” Krasznahorkai’s second novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, came from his dissatisfaction with the first. With a hint of self-deprecation, Krasznahorkai suggested that before he writes he always says, “László, this is your last chance.”

1. Krasznahorkai, making a speech as Irimiás, and Wood, ready to cough up some dough. 2. Crass Molnar and Nick Nicoludis: readers, writers, lobster slingers.

Krasznahorkai concluded the evening with a reading from the English translation of Satantango. Without an introduction, he began reading from a chapter called “Irimiás Makes a Speech.” With a welcoming address of “Ladies and Gentlemen,” Krasznahorkai transformed Housing Works into a town meeting in a Hungarian village. In smooth, inviting tones, which he punctuated with subtle gestures, Krasznahorkai assumed the language of Irimiás, who returns to his home to stifle the tragedy of a young girl’s death and ask for access to the town’s coffers. The audience sat convinced, as if Krasznahorkai were appealing to them.

After the excerpt, Krasznahorkai concluded the evening wordlessly and took a seat next to a stack of new books: Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War and War, all available from New Directions. An autograph line formed, stretching across the store, and I weaved my way out like I’d weaved in, through a mob of eager readers.

***

— Sam Gold is less employed than ever.