Craft

I’m an Award-Winning Short Story Writer and I Don’t Know What I’m Doing Either

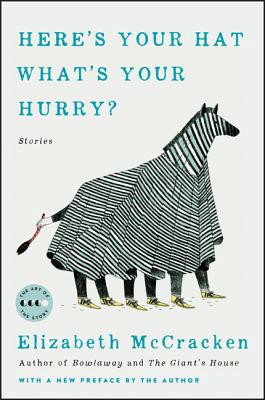

Elizabeth McCracken contemplates short stories upon the reissue of her first collection

A love affair, or a blow to the solar plexus. A ticking bomb that must be allowed to explode. A rebus. A nautilus shell, a string of boxcars, a filmstrip, a scene viewed the wrong way through a telescope, a pond, a snow globe. A magic trick (the sort performed by stage magicians, not sorcerers). A diorama in a natural history museum, with painted backgrounds and half a moose and forced perspective. A piece of photorealistic origami. A magical realist photograph.

What I don’t know about short stories could fill a book. Two books, actually, so far. When I teach, I’m always striving to explain what a short story is, usually by comparing it to something it surely is not. As a teacher (as well as a writer), I love metaphor, which might not speak well of me. It’s like talking to someone who won’t stop doing impressions. I love impressions, too. I love all imitations of greatness. A short story is a single instrument upon which any piece of music may be played; a novel is an orchestra, every song and every sound. A short story is the fin cutting the ocean’s surface that lets you feel and fear the shark beneath; a novel’s the entire Atlantic. A short story is an optical illusion: the hag and then the young beauty and then the hag again, the hag eyeballing you uncannily, the beauty always turning away. Or a vase, and then two faces in profile about to kiss and never getting there. A novel — well, it’s any number of old hags and young beauties and old beauties and young hags and, chances are, a fair number of kisses.

A short story is an optical illusion: the hag and then the young beauty and then the hag again, the hag eyeballing you uncannily, the beauty always turning away.

When I was young, it wasn’t uncommon to hear in MFA programs that short stories were apprentice work. You completed something small to learn how to complete something big, something real. As a grad student I must have written the first 40 pages of half a dozen theoretical novels before giving up, but if I began a short story I finished it. Then, with four stories, I landed a contract for my first book — this was in the olden days, by which I mean 1990, when it was still possible to sell a collection on the strength of four unpublished stories, written by a nobody — and for the first time in my life I was writing for publication. Not in hopes of publication, but for actual publication, with a deadline and a waiting editor. The first few stories I had to write under this particular gun felt all right, not so different from writing for a deadline in school, but I grew to dislike it, and there is at least one story in my first book which, when I remember it, not often, I think, Poor half-formed thing: you were the child of a deadline.

Once I’d finished that first book I began writing novels. I wrote two in a row and declared that I was no longer a short story writer: I had stretched my imagination out of shape and couldn’t go back. Short stories, I explained, were much harder than novels: they showed missteps. Novels were baggy and forgiving; stories had to be both art and perfectly constructed. Harder to mimic real life in a short story, easy to be hokey or overly epiphanic or both. No, I said, I was a novelist now.

There is at least one story in my first book which, when I remember it, not often, I think, “Poor half-formed thing: you were the child of a deadline.”

Then I began to write novels that didn’t go so well, and I rushed back to short fiction. My first story after about nine years of abstinence was pulled from the wreckage of a failed novel. What I’d forgotten: the way I could hold a short story in my head for the entire composition of it, how the first mysterious intimations — a sentence, an image, an exchange of dialogue — were still there when I typed the last line.

When I was young, I scrambled for stories, scavenging through the world looking for scraps. By world I mean stories my friends told me, newspaper articles I read on microfilm, my parents’ family lore, conversations overhead on Greyhound buses, even occasionally the work of other, better writers. There’s a scene in a story in my first book that I only years later realized was stolen from Tobias Wolff’s “Hunters in the Snow.”

Older, I realized that I could will short stories into being. That is, I could decide to write a short story and go picking around my mental debris for a topic, then settle on characters and narrative and structure, and write the thing. Novels — impossible. Novels required an obsession with material and people and a great deal of uncertainty. But short stories required no more obsession than I already had stored up in my brain. Will felt like exactly the right word: I was willing stories into existence. I could work my brain like an electromagnet in a junkyard, turn it on, dip it into the heaps of my own mind, and pull something out. Perhaps not everything picked up was fiction-worthy, but some weird remnant would catch my fancy, and I could build a story around it. This felt like an extraordinary revelation.

I realized I could work my brain like an electromagnet in a junkyard. Not everything picked up was fiction-worthy, but some weird remnant would catch my fancy, and I could build a story around it.

Then, not long ago, I reread Allan Gurganus’s essay “Garden Sermon.” Allan was my first teacher my first semester of graduate school; his work means everything to me. “Garden Sermon” is about, among other things, novel writing, his own first (and great) book Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All, gardening, AIDS in the 1980s, taking care of the dying, the importance of taking things personally, heredity, teaching, compassion. Allan gave a public reading of it when I was his student in 1988.

There in the essay, these words:

“I tell my students: they can will the subject of a story but, a novel? no.”

Not even my revelation was original. I wasn’t ready the first time I heard it; time and other ideas covered it up; then a new wind gusted through the junk heaps, and the idea landed glintingly at my feet. And I thought, mine.

I change my mind about what a short story is nearly every day. So, then: a short story is that junkyard magnet. The form itself attracts. All the pieces of a short story — characters and lines of dialogue, events and images, setting, wild ideas — have been forged separately. Now they’re here, clinging to the one thing they have in common. In the junkyard itself, they mean nothing, a jumble. They are refuse. But once the magnet passes over they jump up and hang together, hub cap to hub cap to old pipe to wrenched-off refrigerator door. You see how they fit together, how they make a shape different from any other collection of scraps. Some of them don’t even touch the magnet: the current runs through the whole assemblage and holds it together. That story your parents always told about the early days of their marriage; the insult that ruined one of your oldest friendships; the morning news of 1962; other people’s writing; your worst memory of fourth grade. Turn on a magnet and watch them fly together.

Today, anyhow, that’s what I think.