interviews

The Hunger of Young, Fat, and Queer Puerto Rican Men

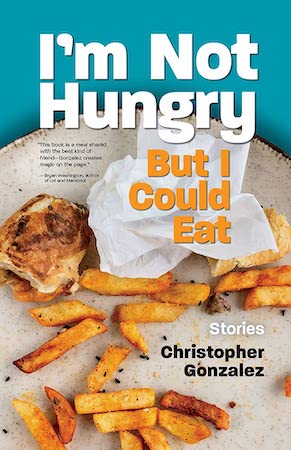

Christopher Gonzalez on the relationship between identity, desire, and intimacy in his book "I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat"

In his debut collection, I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat, Christopher Gonzalez explores the lives of young, fat, and queer Puerto Rican men. In these stories, men hunger not just for consumption but for communion—with friends, lovers, siblings, a cat.

In the title story, a young man eats more than he can stomach to support a distraught friend. In “Little Moves,” Felix attempts to process the death of his older sister, whose strongly held views on masculinity he is still trying to escape. In “Juan, Actually,” an unnamed man’s ride home from a party is disrupted after he’s roped into helping his Uber driver transport the courier he hit to the hospital. Each character in this collection is vibrantly rendered—it’s easy to imagine the lives of these characters outside the bounds of their stories, to wonder what aspects of them would be revealed in other contexts, with other people.

I first met Gonzalez on Twitter, after a literary magazine I read for published one of his short stories (“What You Missed While I Was Watching Your Cat,” included in the collection). I had already been a fan of his writing, how his stories negotiated yearning and humor and sadness and intimacy, and how each line of dialogue felt perfectly attuned to the character speaking it. I was struck by the sincerity he brought to every conversation, whether it be about oat milk, Raúl Esparza’s run as Bobby in Company, or equity in the publishing industry. After knowing Gonzalez as both a friend and a writer, there was no book I looked forward to more this year than I’m Not Hungry But I Could Eat.

I spoke with Gonzalez about the relationship between identity and desire, hookup apps, and the responsibilities of personal growth.

Matthew Mastricova: The inclusion of the author’s note about these characters’ identities fascinated me, partly because I felt these stories explored the tension between how people identify and how people act. Was this something that you aimed to explore?

Christopher Gonzalez: I don’t think an identity is at all an indication of how we actually move through the world. I think it’s a way to find community. It’s a way to label experience, but within those labels, within those identities, there’s just so many types of experiences that overlap and are contradictory, and I’m interested in how we self-identify and how we also move through the world can be contradictory. Whether the character M in “Enough for Two to Share” claims to be straight, but is clearly at least DL, if not bisexual. It doesn’t matter, but he puts up a front for whatever reason and I think people are just walking contradictions all the time. Even for the narrator of that story, he’s out but he sort of plays along with this role of being someone who’s slinking around in the shadows.

MM: I was struck by the types of sex writing in this collection. There’s a section in “Tag-a-long” where there’s this litany of shitty hookups and it made me think a lot about the ways in which sex is often framed as this great release of tension or desire.

There’s a thin line between preference and prejudice and toxic fucked-up attitudes about what you’re entitled to during sex, and I think it’s all sort of murky on the apps.

CG: Sex can be so fraught. I’d say many of the characters in this collection are freshly out of the closet in some way or another, and I feel like hooking up, especially in New York City, can be a very fraught experience. I think for a lot of queer men many of those initial sexual experiences were brought about by the apps and by this filtered communication and distancing so you’re having sex with people you don’t fully know, and I think that’s a very difficult thing. It’s interesting to me that we can string together a personal sexual history based on empty hookups, and in those spaces, we navigate them with all of our identities. I don’t think I really get into the way fetishization happens on the apps in the collection, but when you’re a fat Latinx person, those identities can yield certain types of friction.

MM: Do you think the friction between identity and desire is amplified by apps or is it something that apps have just made more explicit?

CG: Apps are so fascinating to me because apps like Grindr present themselves as almost a Candyland, but within that, there is room for somebody’s fantasy being somebody else’s nightmare. If somebody has a fetish for fat bodies, the person who is fat is on the receiving end of that. I think a lot of us resign ourselves to “this is the only way I can find or have sex or have connections with other people” through these apps that are toxic, so I think maybe both [amplified and made more explicit]. People feel they can be more forthright with what they want, but there’s a thin line between preference and prejudice and toxic fucked-up attitudes about what you’re entitled to during sex, and I think it’s all sort of murky on the apps.

MM: I think about the ways in which like how people signify their identities on apps where it’s not just “I’m looking for a hookup” but “I’m specifically looking for this body type or this ethnicity,” which results in a situation where one’s desire becomes their identity, which is desiring another’s specific identity. As shown in “Enough for Two to Share,” this erases the humanity of the person being desired.

CG: Yeah, you become somebody’s plaything. And I think for some people there are spaces and contexts where you can be into that, but I think there’s a fatigue when that becomes the dominating experience in your sex life, where you’re only desirable because of these traits, but only in these specific situations and it’s only about sex and never progresses to anything beyond that.

I just think it’s exhausting, and I think for the narrator in that story, what’s exciting about the whole interaction for him is that it’s happening very much in the present. You don’t really get the context of what his sexual history is before that night, but in that brief aside you get the feeling that he’s been around the block because he knows how specific types of guys tend to treat guys like him. There’s something exciting about hooking up with someone in an organic way and also that the power dynamic has shifted in his favor.

MM: Do you think the power of explicit sex in a story has a different weight than just the description of it?

It’s more about the action and the persona of being fat, rather than how you feel about your own physical appearance.

CG: Yeah, for sure. I think explicit sex allows you to reveal character in a way that describing it doesn’t. I think it’s less about the sex itself, even if that’s what’s at the surface; it’s about desire and need, which aren’t always inherently sexual. In this context, there is this element in what these characters both feel they need and what they feel they’re getting out of this moment with each other. In the moment they might feel one way, but after there’s gonna be a different light on [that experience]. I purposefully ended before the after. I end that story quite literally on the cusp of a connection in literal body contact.

MM: There’s this tenderness in “Enough for Two to Share,” where fatness is acknowledged in the context of a spontaneous queer meetup but not as a roadblock and without being fetishized or being made the totality of who they are.

CG: Maybe the author’s note was a cheat, in a way, where I could say these characters were fat and then not have to worry about how to get that point across in every single story. [My fatness] isn’t on my mind 24/7, but it comes up, right? And it comes up in sex, which feels like a very natural organic way to mention it, in settings where there’s food, in settings where you feel on display in any way.

M was in no way fetishizing [the narrator]. It doesn’t come up in that way. The narrator also doesn’t dislike his own body, it’s just his body yields these different responses in different sexual encounters. So to have one where he’s allowed to be the more dominant person, where I feel like sometimes when you’re shorter and fatter, there’s this submissive persona that’s projected onto you—it was important to mention his fatness. There’s this tenderness in the way they kiss and it highlights what’s been lacking in other interactions. There would have been no way to write this story without mentioning his body.

For all the stories, it was important to me that these characters were seen as fat men, even in contexts where their body wasn’t particularly highlighted because I think, you know, the reader can’t look away and be like “these fat guys are fucking.” You have to see them fully as that in every story, whether it’s something sexual or not. I didn’t write any moment of particular excessive self-love for the body because that didn’t feel true for any of these characters. I think many of these characters do like their bodies. They’re negotiating liking their own bodies and how they feel in certain spaces in those bodies, and I think there’s a tension there. I think this goes back to your earlier question about contradiction and tension between identity and how you act.

It could very well be that the narrator of the titular story has no problem being fat, but in that specific setting, where you’re aware of your own binging and how this is a practice of, in one sense, being the fat friend who’s always down for a meal and how you have to live up to that. Maybe there’s a part of that that’s pretty shitty and it’s more about the action and the persona of being fat, rather than how you feel about your own physical appearance. I think it’s just a constant negotiation. I could have learned to like my body more than ever, but there are still situations that might bring me back to that mental space where I don’t or didn’t love it as much.

MM: I feel like there’s an expectation, especially amongst queer app users, where people on the DL are less willing to be intimate, but in my reading this was the most emotionally intimate of the stories.

On the apps or a one night stand you can open up, because you won’t have to worry about the ramifications. If you go in being like I’m probably never gonna see this person again, you can immediately let your guard down.

CG: What initially draws them together in the narrator’s mind is that they’re both Puerto Rican, and it sort of ripples out from there. I think they’re both incredibly honest with one another in a way that I think is more difficult when you’ve known someone longer. Ideally, you should be able to vocalize frustration or more difficult emotions with people who you’re closer to, but there’s something built into an interaction that occurs on the apps or a one night stand where I feel like you can open up because you won’t have to worry about the ramifications of having done so, whether that’s conscious or not. I do think if you go in being like I’m probably never gonna see this person again, you can immediately let your guard down without worrying about it later.

MM: What is it about the people close to us, or even just people we know, that keep us from asserting the dignity we deserve?

CG: I think for the characters, there’s always the fear of losing these connections for being fully authentic because if those connections were based on a version of you that wasn’t fully authentic, then I think there’s a fear for them that the minute they sort of assume their true identity or whatever you want to call it, it won’t be well received.

In “Better Than All That,” Justin of course wasn’t out in high school and is in love with his former best friend, but I think there’s that idea of is he actually worried that they’ll be homophobic or is he worried more that he will be revealed as having been a fraud to some extent. And I think there’s room for both. But if your relationship with someone has been built on even a hint of falseness then I think there’s a fear, rational or not, that you can lose it by “coming clean,” so to speak.

MM: Do you think that’s part of the reason the characters in “Here’s the Situation” and “That Version of You” cling to these shitty friends?

CG: I think that’s part of it. I think there’s comfort in those connections for them even though they’re deeply toxic or unhealthy. Something I was interested in exploring in the collection is that these characters are in their early-to-mid-20s and there’s something very formative about those relationships. What happens when you try to break free of them? A lot of these characters are afraid to be their authentic selves, because they’re afraid of losing those connections. Then there’s the question of what comes next after I’ve decided to end this thing. And we don’t really get to see that in any of these stories.

And in those two stories, it’s complicated by the fact that both narrators are in love with, or have at the very least strong feelings towards, their friends. I think for people who are scared to put themselves out there or find someone who’s actually available, it’s almost easier to languish in this connection that you know won’t ever be more than what it is rather than trying to seek out something where you’re uncertain about the result. That was one of the major through lines I was working through in this collection—wanting to change your situation but being completely terrified and debilitated by the idea of doing so. Which is why, I think, each story ends for the most part on this subtle shift where you know something has changed. It might not seem that big, but for those characters it’s massive.

MM: In “Better Than All the Rest,” the main character has literally forgotten how he performed his identity while in survival mode. Do we have a responsibility to others in changing?

CG: I think our personal journeys and self-growth will always result in the relationships around us shifting in one direction or another. I think we are all capable of enacting unintentional harm, and that, to me, is more interesting than intentional cruelty—casual cruelty or, in the case of “Better Than All That,” this cruelty that was a means of survival. It was a tool that played into homophobia and internalized homophobia, but had actual consequences.

That was one of the major through lines in this collection—wanting to change your situation, but being completely terrified and debilitated by the idea of doing so.

As far as what our responsibility is to others, I think the difficult thing is to acknowledge when harm has been done. I think sometimes it’s harder to do when your main goal was self-preservation, but I don’t know what [being responsible to others] looks like, to be honest. I don’t know if that’s apologizing, if that’s owning up to it. I don’t know if that’s extending kindness in a situation later in life that echoes a situation where such harm was enacted, but I think for all these characters who wish to grow, for all of us, I think there has to be recognition of what it took to get there, and what it took isn’t always sunshine and rainbows.

It’s a terrible way to put it, but so often we’re like “I’ve gone through a lot to get to where I am,” and that’s true. I think we all have that moment where we’re like ”Wow, I’ve grown as a person,” but I think in order to grow sometimes we’re just a little unaware of who we might have stepped on, or we’re so focused on our own insecurities or fears we didn’t realize somebody else needed help. And I think it’s complicated.

MM: I think one of the interesting tensions of writing identities with fidelity is that, as you said earlier, you’re not always aware of every facet of your identity at once. I was particularly interested in your approach to writing bisexuality and bisexual characters.

CG: It was something that, as I was writing the book, came up with first readers of the stories being like “Well, it was a little unclear. Maybe he’s gay, maybe he’s—” and part of me being like “Maybe it actually doesn’t matter whatever the label is.” They’re bisexual because they are and I didn’t feel like it was necessary to unpack that. And of course in “Tag-a-long” there’s that moment of “Well, it must be easier to date because you’re bisexual.” Part of writing this book was taking the piss out of those interactions I’ve had, those invalidating experiences. There’s nothing in “Blank White Spaces” that would suggest explicitly the narrator is bisexual. The person he’s longing for or has had this intense relationship and breakup with is a woman,m but I think if you were to write another story about that character, maybe it would come up that he has had feelings for men or maybe it wouldn’t.

Going back to the author’s note, part of it was also a level of defensiveness. I’m not going to justify their sexuality in any way. It was very important to me for readers to not see the character in “Packed White Spaces” as straight. A big part of the collection is just these characters who are feeling unseen in their full complexity and [sexuality is] one facet of their character, even if it’s not a part of that story. There are stories where it’s a conscious choice to mention it specifically because a character has had many relationships, like in “Juan, Actually,” but that’s the thing! There’s no one way that bisexuality works, and the idea that just because somebody has had more experience with men doesn’t mean they’re any less bisexual.