interviews

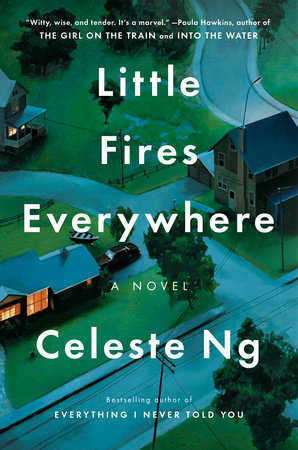

In Her New Novel, Celeste Ng Goes Home

The author of ‘Little Fires Everywhere’ on writing about her hometown and motherhood

Like her best-selling 2014 debut, Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng’s new novel Little Fires Everywhere looks at communities and their complex, often fraught, relationship to identity. Ng focuses her thoughtful gaze on the kind of successful and self-satisfied hamlet found across suburban America — the type of place where fitting in requires not only the possession of certain attributes but the absence of others.

The community in Little Fires Everywhere is Shaker Heights, a real Ohio town (just ask Ng, who grew up there), created in 1914 by two railroad mogul brothers who envisioned a perfectly planned alternative to Cleveland’s city living. Rules abound, from town ordinances regarding the layout of the beautifully manicured cul-de-sacs to the unspoken decorums practiced by the idealistically progressive yet practically traditional society.

Into this landscape come Mia Warren, a photographer and free-spirit, and her bookish daughter Pearl. Mia has decided to pause their long-standing peripatetic lifestyle. They become tenants of the Richardsons, a wealthy, well-respected family that’s powered by the matriarch, Elena, a woman who seems to embody Shaker Heights itself. Though the four Richardson kids are entranced by Mia and Pearl, Elena finds herself at increasing odds with her tenants. When a local white family gets into a contested adoption and custody battle over an abandoned Chinese American baby girl, lines are drawn in the sand.

Little Fires Everywhere feels especially resonant today, as much of our country struggles with the reality of living in ever-less homogenous environments. But what elevates the novel beyond timeliness is that Ng doesn’t stick to examining the obvious opponents to change. She asks hard questions of people who believe themselves to be progressive and pro-diversity yet show a caustic reticence to individuality and even an unacknowledged racism when they’re asked to open their arms or adjust their lives.

I had the pleasure of talking with Ng over email about writing the novel before Trump, the challenges of writing about your home town, and the things she loves about Twitter.

Carrie Mullins: Tell me about Shaker Heights. In the book, the town is a bit like Pleasantville, and I felt a lingering claustrophobia as we moved among the lovely, landscaped houses. Why did you decide to set the novel there?

Celeste Ng: The novel grew out of my desire to write about my hometown — so it couldn’t ever have been set anywhere else. I had been away from home for about a decade at that point, and I was at the stage where I started to look back on those formative hometown years with some clarity. I still remembered them clearly, but I had also come to see that many of the things I’d grown up with were unusual.

I touch on some of these things (which are at both ends of the keyboard, so to speak) in the novel itself: the obsession with order in the community, the fact that we were so focused on improving race relations that there’s a race relations group at the high school. But those are all really manifestations of a larger issue that is really what sets Shaker Heights apart, and which to me is the heart of the novel: the tension between the almost hippie-ish idealism and the almost anal fixation on regulating everything. It stretches back past the founding of the town to the Shakers who once owned the land — it’s practically in the soil.

CM: Are there challenges to writing about a place that you know so intimately?

CN: In writing about a real place, I felt a responsibility to try to be both accurate and fair. This is especially true because Shaker Heights is a place that I love even as I have reservations, and criticisms, of some aspects of it. I hope I wrote this book at the sweet spot where I could be truthful — like one of those magic eye pictures where you have to be at the exact right distance to see the image.

I hope I wrote this book at the sweet spot where I could be truthful — like one of those magic eye pictures where you have to be at the exact right distance to see the image.

CM: The novel — though not necessarily all the characters within it — is very cognizant of how money and status affects people’s attitudes towards race and identity. For example, Bebe, an impoverished immigrant, is treated very differently than Brian, the son of two professionals. With everything that’s going on with DACA and, well, our government at large, highlighting this intersection feels especially timely. Of course there’s a time lapse between writing a novel and it hitting the store shelves; has the current political environment changed how you think or talk about the book, or how you think it will be received?

CN: It’s absolutely changed how I see the book and how I suspect it will be received. I wrote it at a very different political time — about from fall 2015 to midsummer 2016 — and I had been thinking about it and the plot and the characters since 2009. So it wasn’t written with our current times in mind, but now, in the Trump era, I can’t help but see it in conversation with what’s happening in our country now.

I guess this says two things: first, that the meaning we see in a book is always influenced by where we, as readers, are at the moment we read it. When I reread books I loved as a teenager, for example, I interpret them very differently now that I’m an adult. But the words on the page haven’t changed — so the change has to be in me. The second thing is this: the book takes place in 1997, and the fact that it feels so relevant to our current time suggests we haven’t come quite as far in the past 20 years as we’d like to think.

11 Novels That Expectant Parents Should Read Instead of Parenting Books

CM: Speaking of current events, I’m one of the many fans of your Twitter account. I think I came on board for #smallacts and stayed for the mix of humor and candor that has gained you over 29,000 followers. As someone who is hopelessly inept at the posting side of Twitter (I’m basically a lurker) all I can ask is, 29k!? Is having that kind of presence exhilarating or anxiety-provoking? Does being so visible to your audience have any effect on your fiction writing?

CN: I love that you say you came on board for #smallacts — I’ve had followers say to me in the past few months, “I didn’t know you wrote a book, I thought you were just funny on Twitter!” Honestly, I don’t know how I ended up with so many followers, but I’m happy they’re here and hope they get something out of the randomness that is my Twitter feed.

Even now I don’t think I’ve quite gotten my head around the audience that I have there; it still amazes me that anybody wants to hear what I have to say. I try to think of it as thousands of people standing in my corner cheering me on. And I like to listen as much as I can there myself — my favorite things are when people share things they love (articles, pictures, pets) and when they tell stories about themselves or others. When I see what other people are talking and thinking about, I feel like my brain’s been enriched, like mixing compost into soil. At its best, Twitter reminds me how smart and funny and interesting and witty and weird and kind people can be — basically, that we’re all human and that humans are both loveable and fallible. I think that feeds my fiction as well.

CM: Both this and your first novel, Everything I Never Told You, are books that play with perspective. What interests you about coming at one event from multiple points of view?

CN: I didn’t plan for that to happen, but it’s true! I’ve always been interested in how we piece stories together, how we make sense out of the jumble of events that make up life. So an omniscient narrator is a natural move: the narrator is piecing things together just as the reader does, helping the reader make connections and hear resonances. I’m also fascinated by the hard fact that we can never perfectly communicate what we mean: we do our best with words and pictures and gestures, but there’s no direct way to take your thoughts or feelings or experiences and put them in someone else’s brain. There’s always going to be something lost in transmission. Which means to have any hope of seeing the full picture, we need to hear multiple perspectives.

There’s always going to be something lost in transmission. Which means to have any hope of seeing the full picture, we need to hear multiple perspectives.

CM: It’s the contested adoption of May Ling/Mirabelle that brings the characters’ individual perspectives together. The question of identity is an issue for any adoptee, but it’s magnified in a transracial adoption. What led you to choose and investigate this situation for a novel?

CN: I’d remembered hearing about a transracial adoption case when I was in high school that divided the Asian community, but wasn’t able to find out anything more about it. As soon as I remembered it, though, the basic questions it raised seemed to tie all the threads of the novel together: race, class, parenting, identity. Then, as I began to research high-profile custody battles, the story came more and more into focus, and I realized it belonged in the book.

CM: The ironic thing about this terrible situation — a baby is abandoned, then fought over in court — is that there is still so much love flying off the pages. It got me thinking about the challenges of capturing motherhood; how do you show how intense it can be, and how complicated, for a varied audience? Stories about motherhood are also often dismissed as ‘female’ narratives or even ‘chick lit.’ Do you ever worry about those labels or having to prove that the mother/child relationship is worthy of literature?

CN: It infuriates me that stories about motherhood — and women in general — are so often and so easily dismissed. They are so obviously worthy of literature that I don’t even know how to begin arguing this point.

It infuriates me that stories about motherhood — and women in general — are so often and so easily dismissed.

It wasn’t my specific intent to challenge that view, but I hope I wrote a book that acts as a counterpoint. But while we have to stay aware of — and vocal about — this issue, it’s ultimately an attempt to distract us from the work. I think of the Toni Morrison quote where she says that all of racism is an attempt to keep you from doing your work. Here it is, because it’s worth sharing in full: “The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.”

The best thing we can do to change things, aside from pointing out the double standard wherever we see it, is to make good work about motherhood, work that’s so indisputably good that its value as literature is self-evident and undeniable. And I think people are doing that, so I hope this attitude is changing.