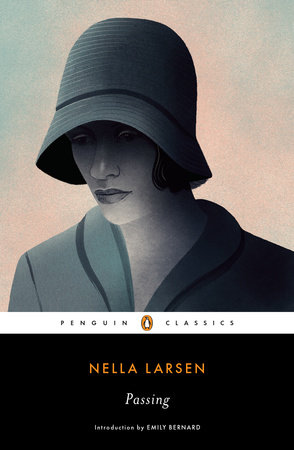

Books & Culture

In Nella Larsen’s “Passing,” Whiteness Isn’t Just About Race

The classic book deals with the complicated intersection of race, class, and culture

Passing is a work of fiction, but it is a true story about the world in which its author, Nella Larsen, lived. To describe it simply as a novel about a black woman passing for white would be to ignore the multiple layers of its concerns. Passing is about the monumental cultural transformations that took place in American society after World War I. It is about changing definitions of concepts like race and gender, and the inextricable relationship between whiteness and blackness. It is a meditation on the uneasy dynamic between social obligation and personal freedom. It dramatizes the impossibility of self-invention in a society in which nuance and ambiguity are considered fatal threats to the social order. The novel is an indictment of consumer culture and the dangers it poses to personal integrity. It reveals the power of desire to transform and unhinge us, and the lengths to which we will go to get what we want. Passing is about hypocrisy and fear, secrecy and betrayal. It is a universal story of the messiness of being human as it is portrayed in the particularly explosive relationship between two black women, Clare Kendry and Irene Redfield.

‘Passing’ is a meditation on the uneasy dynamic between social obligation and personal freedom.

Irene and Clare have not seen each other in twelve years when they reunite by chance on the roof of the Drayton Hotel in Chicago, where both women are enjoying a respite from a blazing hot August day. The Drayton is an exclusive hotel, and not one in which African Americans, or Negroes, to use the parlance of the day, would be welcome. In fact, on the fateful day of their reunion, both women are passing for white.

In Passing, race is revealed to be, in part, a function of performance (the novel is structured in three sections — Encounter, Re-Encounter, Finale — much like acts in a theatrical piece), and blackness a matter of perception. Of the two women, it is Clare who appears to be so convincingly white that not only does Irene fail to identify Clare as a Negro, she doesn’t recognize her childhood friend at all. Even after Clare introduces herself to Irene, Irene still doesn’t recognize her or her blackness. When Clare uses her nickname, Irene searches her memory: “What white girls had she known well enough to have been familiarly addressed as ’Rene by them?” By contrast, Clare identifies Irene immediately. Irene squirms under Clare’s unflinching stare, terrified of being seen for who she is, and also afraid of the embarrassment that would result from being ejected from the hotel.

It is only when Clare emits her distinctive laugh, which is “like the ringing of a delicate bell,” that Irene finally recognizes her old friend. As the women talk, Clare appears more and more black to Irene. “Ah! Surely! They were Negro eyes! mysterious and concealing,” she thinks as she feasts her own eyes upon Clare’s stunning features. “There was about them something exotic,” she thinks. As she is observing Clare, Irene is simultaneously making her up, inventing her — and inventing race, too. Clare isn’t any more of a Negro after she reveals herself to Irene than she was before. As Irene confesses to another character later in the novel, no one can tell just by looking.

According to the guidelines of genealogy, Clare’s claims to blackness are tenuous. Her grandfather was white. Her father was the product of her grandfather’s dishonorable relationship with a black woman. Somewhere along the way, there had been money, but her grandfather squandered it. There is no mention in the novel of Clare’s mother.

Once her father died, his pious aunts took Clare in, not as an expression of filial love but rather a sterile sense of Christian duty. They treated her like a servant, and forbade her from revealing the truth about her racial identity. Their bigotry was frank. “For all their Bibles and praying and ranting about honesty, they didn’t want anyone to know that their darling brother had seduced — ruined, they called it — a Negro girl. They could excuse the ruin, but they couldn’t forgive the tarbrush,” Clare tells Irene. Clare was forbidden even to mention Negroes to the neighbors, much less discuss the South Side, where Irene and her friends lived in Chicago. It was easy for Clare to dispose of such an unhappy past, which was bankrupt of love as well as money.

Clare Kendry has not used her fair skin to make a political statement; she has not been passing in order to undermine and subvert the system of white supremacy. There has been no greater good. Instead she has been passing purely for personal gain. Although she grew up in the same racial world as Irene, her social circumstances were radically different. Among their cohort of middle-class girls, “Clare had never been exactly one of the group.” Her father had gone to college with some of the other girls’ fathers, but he had somehow wound up a janitor, and “a very inefficient one at that.” He was also a violent alcoholic who would ultimately die in a bar fight. Among Irene’s earliest memories of Clare are images of “a pale small girl sitting on a ragged blue sofa, sewing pieces of bright red cloth together, while her drunken father, a tall, powerfully built man, raged threateningly up and down the shabby room, bellowing curses and making spasmodic lunges at her.” The stubborn little girl boldly stitching together the bright cloth in defiance of her father’s rage would grow into a young woman who defied fate, custom, and white supremacy by crossing the color line. But it wasn’t racial self-hatred that catapulted Clare into whiteness; it was the shabby room. Clare passed for white because she hated being poor, not being black.

Clare passed for white because she hated being poor, not being black.

All passing narratives are about class as much as they are about race. One never passes down the social ladder; black characters become, or pose as, white in order to improve their material circumstances, or gain access in general to opportunities for personal, social, and professional advancement. The choice of individual comfort over the advancement of the race as a whole is always rendered as wrong; in most passing stories, material ambition and moral ruin are directly correlated. By the time some passing subjects recognize the truly degraded implications of their decisions to engage in racial masquerade, it is too late. In the film Imitation of Life, the main character comes to her senses only after she finds out that her choice to pass has literally killed her mother. The denial of the black mother is often the surest sign of the low character of those who choose to pass. The narrator in the short story “Passing” by Langston Hughes gets a better job as a white man but his financial success requires him to ignore his own mother as they pass each other on the street. “That’s the kind of thing that makes passing hard,” the narrator sums up in a letter to his mother, “having to deny your own family when you see them.”

Clare is a gambler, playing the high stakes game of racial roulette. For her, passing is a sport, and she is unrivaled in her technique.

Clare Kendry is markedly different from other passing subjects in American literature. For one, she is not concerned with the moral implications of passing for white. Unlike other black characters whose passing enables them to marry white people, Clare does not pass for love. Even though she views passing through the lens of rank materialism, ultimately she sees passing as play. Clare Kendry is not an incarnation of the “tragic mulatto” figure, inherently alienated and adrift, whose mixed blood dooms her to racial purgatory. She is not wandering in the interstices of black and white. Instead, Clare is a hunter, stalking the margins of racial identity, hungry for forbidden experience, “stepping always on the edge of danger.” She is a gambler, playing the high stakes game of racial roulette. For her, passing is a sport, and she is unrivaled in her technique. Clare desires many things, among them to be among Negroes again. But ultimately, the true nature of her driving need is as opaque as the “ivory mask” she wears.

Irene is tied to race out of duty; Clare’s relationship to blackness is affective. “You don’t know, you can’t realize how I want to see Negroes, to be with them again, to talk with them, to hear them laugh,” Clare confesses to Irene. As a woman motivated by passion and excited to cross lines of propriety, Clare has a lot in common with the writer who dreamed her up: Nella Larsen.

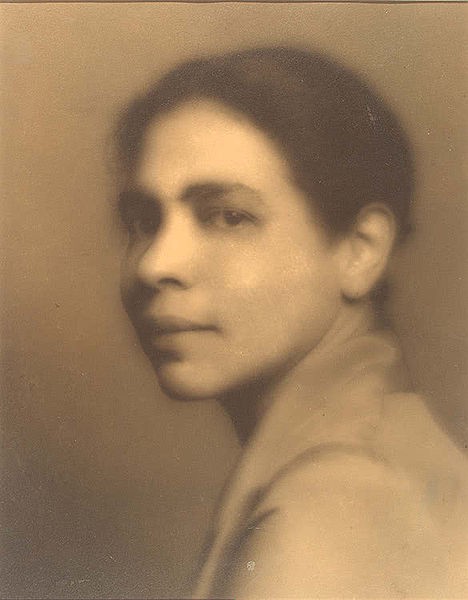

Nella Larsen was born Nellie Walker in 1891 in Chicago. Her mother was a Danish immigrant and her father an immigrant from the Danish West Indies. Nella’s father disappeared from her life when she was young. Her mother married a fellow Danish immigrant, Peter Larsen, with whom she had another child. Like many fiction writers, Larsen incorporated elements of her own life into her writing. She shared with Clare the experience of being unwanted by white family members; neither Peter nor her half-sister acknowledged the ties that bound them. Like Clare, Nella was born poor and on the wrong side of town. Not only did Larsen spend her childhood in the vice district of Chicago, she was confronted by other dangers: a city in which the crossing of racial lines was unwelcome and cost those who disregarded them dearly. The rigid lines were officially underscored when, in 1920, the category “mulatto” was dropped from the census. There was no room for individuals whose bodies failed to conform to convention.

Nella was introduced to the world of the black bourgeoisie — the world in which Irene moved easily — when she was a student at Fisk University. There she bristled at the strict codes of dress and conduct. In her 1928 novel Quicksand, Larsen describes the disdain that the main character Helga Crane has toward the smug, insular world of the black elite at the fictional college of Naxos (an anagram for Saxon). “These people yapped loudly of race, of race consciousness, of race pride, and yet suppressed its most delightful manifestations, love of color, joy of rhythmic motion, naïve spontaneous laughter.”

Ultimately Larsen was expelled from Fisk, most likely for violating dress code. Larsen went from Fisk to Denmark, where she had spent time as a child. She returned to the United States and enrolled in nursing school, taking a position as head nurse at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, the incarnation of the vision of Booker T. Washington, and along with Fisk, a model for Naxos. It was known as the “Tuskegee machine.” In Quicksand, Helga reflects on her school: “This great community, she thought, was no longer a school. It had grown into a machine.” Larsen found the working conditions at Tuskegee untenable. She resigned in 1916.

A few years later, she married Elmer Imes, who was at that point one of two African Americans to have ever held a Ph.D. in physics. The couple moved to Harlem, where Larsen took a job at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Soon her life as a writer would begin.

As Elmer’s wife, Nella began to spend time with intellectual and cultural luminaries of the 1920s, black men like James Weldon Johnson, Walter White, and W. E. B. Du Bois. These men were architects of the Harlem Renaissance, authors of crucial philosophies that captured the concerns of black intellectuals of the moment. They were also central figures in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, an organization for black progress that Du Bois helped to found in 1909. Irene Redfield, who prides herself on being a ticket taker for a ball for the Negro Welfare League, would have been impressed by the company Larsen kept.

It is safe to say that both Nella Larsen and her character Clare Kendry would have had easier lives as mixed-race women in the 21st century. If the 1920 census, with its removal of “mulatto” as a viable racial category, officially erased the experience of being mixed-race in the United States, the inclusion on the 2000 census of categories that allow individuals to identify for the first time in history with more than one race has already generated new stories. According to the 2010 Census Brief, since 2000, the population reporting multiple races increased by 32 percent. Already, the structure of the new census has enabled people with complex racial backgrounds to more aptly define themselves.

It is safe to say that both Nella Larsen and her character Clare Kendry would have had easier lives as mixed-race women in the 21st century.

Unfortunately, the script had already been written for Clare. She was a woman who insisted on being free, and she paid for the crime of her hunger not only to defy racial convention but also the customs of gender, as well. The men in the novel are world explorers, or yearn to be: Jack Bellew is an international banker; Hugh Wentworth has “lived on edges of nowhere in at least three continents”; Brian Redfield longs to abandon American racism and move to Brazil. Clare is the true adventurer, however. Her wanderlust is domestic but perhaps more dangerous in that it is not structured by travel or outlined in a map but rather a function of her everyday life. Her literary descendants, such as Janie Crawford in Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston; Sula in the eponymous novel by Toni Morrison; Birdie in Caucasia by Danzy Senna; and the protagonists in Interesting Women by Andrea Lee, also live dangerously by pushing the boundaries of social convention. But in the high stakes games that Clare plays in 1929, the house always wins.

“What is Africa to me?” muses the speaker in “Heritage.” Where does race reside? In blood, ancestry, or emotion? How can it be identified, much less quantified? Is it absurdity or a mystery? Race is a function of law, history, and politics, not science. Yet there is an ineffable quality to blackness, a mysterious factor that drives Clare to risk everything in order to “see Negroes, to be with them again, to talk with them, to hear them laugh.”

It is this ineffability, the mystery that Clare embodies, that Irene cannot bear. She curses race as a yoke, but what she ultimately rejects is not a racial bond with Clare, but the awareness that identity itself is transitional, as mobile as the trains that made it possible for millions of African Americans to leave the South during the Great Migration, and the railroad car that provided the platform for Homer Plessy’s historic confrontation. The self itself is unstable, just like the concept of race.

At the end of the novel, Irene finishes her final cigarette and throws it out of a window, “watching the tiny spark drop slowly down to the white ground below.” It is impossible not to associate the cigarette sparks with the vitality and danger that Clare brought into her life. But Clare Kendry is unforgettable. After all, when a fire goes out, one does not necessarily remember the ashes. But one certainly remembers the brilliance of the flame.

Adapted from PASSING by Nella Larson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Introduction copyright © 2018 by Emily Bernard.