essays

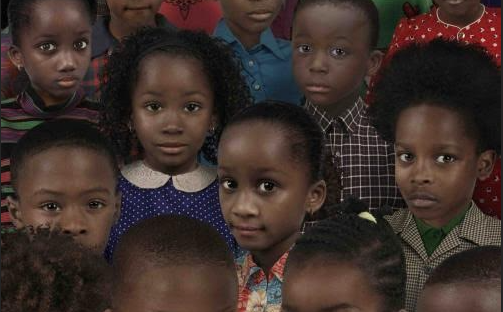

Innocence Is a Privilege: Black Children Are Not Allowed to Be Innocent in America

Days ago an interviewer asked me how Delores — one of the main characters in my debut novel, Here Comes the Sun — could be so cruel and unapologetic in how she treats her daughters, Margot and Thandi. It wasn’t the first time I’ve heard the question. The same question was posed in front of an audience of librarians in Chicago a month earlier. Had I listened closely, I might have heard the rapid blinking of eyes in the pause before I answered. Faces were drawn into contemplative lines as each person seemed intent on knowing how a mother could relay to her daughter that no one loves a black girl, a black body. Not even herself. Truth is Delores loves her daughters so much that she will be the first to break them.

As I reflect on the recent killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile — the latter who was shot and killed inside his car; his girlfriend Diamond Reynold’s four-year-old daughter bearing witness — I grapple with the loss of the cloak of protection we have as children called innocence. For black children, innocence is snatched away too soon, a brutal initiation into a frigid world.

Innocence, like freedom, is a privilege.

In his memoir, Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates ruminates over the loss of his son’s innocence as his son becomes more aware of racial inequalities in his own country. He laments, “I write to you in your fifteenth year. I am writing you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes…”

Innocence, like freedom, is a privilege.

Many black parents tell black children to strive; to seize opportunities that will enable upward mobility. However, they also give their children a poison capable of eroding black children’s innocence. They tell them to be twice as good; that there is no room for failure or mistakes. What settles at the base of their throats is the weighted truth that inevitably begins with, “No matter how hard…” It’s understandable that parents would rather have this poison — this “No matter how hard you try; you will never be seen as equal” — settle at the base of their throats or get lodged like a calcified stone in the left side of their chest than to see the healthy light dim in their children’s eyes. Had this poison been exchanged in every kiss goodnight, every night-time prayer, perhaps black children would be more guarded; our hopes and dreams placed in the hands of a god we’re told will have mercy. But we can’t have mercy. Not with history constantly chasing us and pulling us under, yanking us out of our dreams and into the mouths of hatred.

In Jamaica, my mother and grandmother taught me and my siblings to say “God willing” whenever we uttered future plans since no day is promised. I’ve been using this term more and more lately with everything that has been going on — from the recent Orlando shooting and last year’s massacre at the AME church in South Carolina to Sandra Bland, Mike Brown, Eric Garner, and more. I once resented the term, “God willing,” always shrugging my shoulders at my grandmother, though she was a woman who knew defeat like the life lines in the middle of her hand.

When we consider the social atmosphere thick with violence, racism, sexism, classism, xenophobia, and homophobia, we begin to understand that our parents’ warnings are for our own survival. But at what cost? Those moments of suspended play are unforgettable given the traumatizing way in which our innocence was snatched. They become indelible memories of bliss marred by looming shadows of reality. Something as simple as overhearing the news reports or catching a glimpse of worry creasing our parents’ faces could trigger the first blow. Some of us were called in after a game of soccer, the lone ball left to the elements outside, partially deflated, as our mother or father or grandparent — finally finding the courage to explain what we saw or heard — lowered their voices, which would forever resonate within us. Some of us were in the middle of playing dress-up, barely standing upright in high heels — a testament that we were way too small to walk in our mothers’ shoes much less carry the weight of her burdens. In James Baldwin’s story, Sonny’s Blues, this sentiment is apparent as the narrator recalls the moment in his childhood when he lost his innocence:

[My mother] would be sitting on the sofa. And my father would be sitting on the easy chair, not far from her. And the living room would be filled with church folks and relatives. There they sit in chairs, all around in the living room, and the night is creeping up outside, but nobody knows it yet…for a moment nobody is talking, but every face looks darkening like the sky outside…Everyone is looking at something a child can’t see. For a minute they have forgotten the children…the darkness in the faces frightens the child obscurely…something deep and watchful in the child knows…And when light fills the room, the child is left with darkness.

In Toni Morrison’s Beloved, the protagonist Sethe kills her baby girl by slitting her throat with a cutlass before the slave owners could get to her. Seth explains, “My love was too thick…I felt what [slavery] felt like and nobody walking or stretched out is going to make you feel it too.” If that’s not mercy, then I don’t know what mercy is. As gruesome as this act may seem, it is the very same act performed over and over again by black parents each time they have to sit and disclose to their children that the world hates them for the color of their skin. That they will never be seen as equal to their white playmates on the playground. That the neighbor might call the police if they ever sneak in the window after curfew. Or, god forbid, leave the house in a hoody to buy skittles and a soda at the corner store.

It goes without saying that black parents and parents of black children see the world their children exist in as a dubious one. In order to control their circumstances, they use caution. Some — like my character Delores — use cruelty. They each have the same goal: to protect.

In Jamaica my mother and grandmother used flogging as a way to discipline me and my siblings. Not out of hate but out of love twisted with fear — fear that if they didn’t do it, society’s punishment for bad behavior would be worse. And though flogging is rooted in the bloodied history of slavery, my guardians saw it as redeeming.

It goes without saying that black parents and parents of black children see the world their children exist in as a dubious one.

Truth is, there is nothing parents can do. There is nothing black parents can do to protect their children and their children’s innocence. Diamond Reynold’s four-year-old daughter can attest to this as she watched Philando Castile take his last breath. The scene, in her eyes, will forever be painted red, the sound a resonating firecracker — like those fireworks, fleet and bright, during the fourth of July weekend — the last time she would ever see her step-father-to-be’s smile, the sun and moon in his eyes. Even as her distraught mother leaned in to wake him up, blood soaked and lifeless, the little girl already knew he was gone. Something — that inkling one gets when innocence no longer masks the sharp edge of reality — nudged her; and she in turn comforted her mother.

The breaking of innocence should not only be black parents’ responsibility. It should be the responsibility of white parents as well. At what point should white children be made aware of their privilege? Their innocence might not be as mangled as that of black children within the context of racism, but a conversation would surely save a life someday.

At what point should white children be made aware of their privilege?

Currently, the black body count is building, mounting into an insurmountable pile. Claudia Rankine illustrates this best in her book Citizen, documenting an ever growing list of names of black men and black women killed by the police. Surely black parents aren’t wrong for trying their very best to preserve the hopes and dreams and innocence of their children. But what good does it do when we hide the truth? We have lost too many dreamers that way. A black child cannot afford to be fooled. Delores knew this in Here Comes the Sun. She knew that her daughters would not fare well in a society that despises them. Diamond Reynold’s four-year-old daughter now knows that no one loves a black girl enough to spare her innocence.