interviews

INTERVIEW: Catherine Lacey, author of Nobody Is Ever Missing

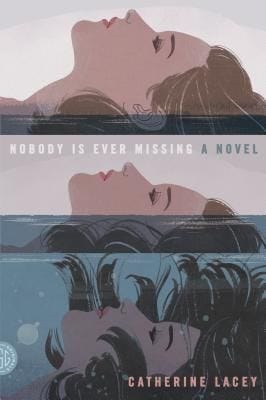

Catherine Lacey’s debut novel, Nobody Is Ever Missing (FSG Originals), was released this summer to wide acclaim. It’s a difficult book to describe. A young woman named Elyria leaves New York and her husband to hitchhike around New Zealand. She doesn’t have much of a plan and seems an unlikely candidate for epiphany. Her thoughts run dark. Lacey’s sentences are long and spiraling and you often emerge from them with the feeling that that you’ve somehow been cut to the quick. None of this makes for easy summary or appraisal. But Nobody Is Ever Missing isn’t necessarily the kind of book you want to tell all your friends about, anyway. It’s the kind of book that makes you wonder whether the whole business of having friends and family and husbands and jobs is really worthwhile, whether you might not be better off just buying a plane ticket and vanishing into a new life, at least for a little while.

I met Lacey in early September at a bar in Brooklyn. Her publicity obligations for the book were mostly fulfilled and she looked relaxed. She had just returned from a cruise, during which, she told me proudly, she had managed to obtain a staff badge granting her certain privileges and listing her job title as Just Cruisin’. We spoke over the course of an afternoon about dark comedy, the power of disappearing, religion in the South, and why women authors are so often confused for their characters.

Dwyer Murphy: In Nobody Is Ever Missing, your narrator, Elyria, has an especially distinct, morbid voice. I’m curious how it first came to you. Was there a passage or a scene where you really found out who she was, what she sounded like?

Catherine Lacey: For a while, she wasn’t giving me much, but then I started working on a passage where she’s narrating a letter to her husband, and I understood how she saw the world, her matrix of darkness. Once I had that, I could write any scene from her perspective. I could walk her into this bar right now and have her order a drink. It was like that game, Connect Four. I’d drop in the chip and it might bounce around a little, but there was only once place it was going. Her gravity was just there.

DM: We’re talking about Elyria as such a dark person–and she is–but it’s a funny book. Where do you think the humor comes from here?

CL: I find it funny to see a person stuck. It’s almost like physical comedy, with Charlie Chaplin and his cane, and you laugh because he can’t stop dropping his cane. Elyria can’t meet somebody and not think about that person’s impending death. She can’t escape her own hopelessness. Some people find that deeply unfunny. One of the first interviews I did, the interviewer took issue with a line on the galley about the book being a “pitch-black comedy.” She insisted it was not a comedy. People seem pretty split. For me, it’s funny. Elyria’s on the run from her life, she’s alone, she’s thinking too much about death–it’s a perpetual cane drop.

DM: You wrote a piece for Buzzfeed Books where you try to delineate which parts of Elyria come from you and which don’t–you talk about making up a Venn diagram even. Has that been a nagging issue, people assuming she’s just straight you?

CL: I know it’s a natural thing to wonder about when you’re reading a book–how much of this character is the author–but I think that women are asked that kind of question more often than men are. As a culture, we don’t have many ideas of what a young woman can be. We have a big range for men. We have a hundred years of archetypes and stories and mythologies. (That’s part of why I think women could more easily write from a male perspective than men could write from a female perspective–growing up, we’ve just been fed so many male narratives, that perspective becomes a part of us.) But for a young woman, we have this small range–she can be a mother or not-a-mother or a slut, and that’s about it. Good, bad or barren, basically.

So people see Elyria, and she’s not really any of those things, and they think she must be personal. She must be me. I think our culture gives a little more credit to men’s ability to be completely generative. I think there’s an assumption that women are always grappling with themselves, making art about how hard it is to be them, to be a certain woman.

DM: I’ve come across a lot of people debating whether this is a feminist book, whether it supports feminist ideas, whether Elyria is herself a feminist. I wonder if you have an opinion on that, or whether you resent even having the debate?

CL: I don’t resent it. It’s an interesting question. There’s no standard definition of what counts as feminist book or character or plot line. If this were 1914, it would probably be a feminist book, because back then it was more radical for a woman to leave her husband and go off somewhere to be alone. But now, Elyria’s just a human being who leaves a relationship. Her being a woman is not a huge part of the story, and the faults in her relationship aren’t a matter of her husband being a chauvinist asshole. There was a line in Dwight Garner’s review about the “Smart Women Adrift Genre,” that a protagonist from a Joan Didion or Renata Adler novel could eat Elyria like an oyster. I thought that was just perfect. They really would, like an oyster.

DM: In that review, Garner seems to see Nobody as being about a distinct kind of ennui you experience in your late twenties, but I’ve heard other people, like Sasha Frere-Jones, say that Elyria could just as easily be middle-aged. Do you think that the ennui Elyria’s feeling is specific to an age or a period of life?

CL: Probably I don’t get to decide, but I like to think her unrest is broader. We have an idea that this kind of ennui–feeling adrift and confused about what you should be doing with yourself and with your life–only happens when you’re in your twenties, but I think that probably we continue to have those moments forever. Probably it comes back to you every few years, like a fugue, and you wonder all over again whether you made the right decisions, did the right things.

DM: Did you look to any particular books when you were figuring out how to write a novel about disappearing from a marriage? When Elyria first gets to New Zealand, I kept thinking about Rabbit Angstrom driving away from Mount Judge.

CL: Well, you brought up Updike and now I’m going to go on a rant. I’ve tried, but I just can’t get past the fact that Updike and dudes like Updike saw the world in such a dickish way. I know they’re a product of their times, and I know that some people can read them and overlook the fact that there are so few complicated women in their books and strong homophobic overtones and just blatantly racist shit, but I don’t want to overlook it. I want to read authors who could see that stuff for what it was–fucked up. I want to read authors who see people more fully and completely and with more empathy. Updike’s a brilliant writer–on the sentence and plot level, you can’t argue with him–but lots of people can write good sentences while also appreciating a full range of humanity. Good sentences and plots don’t do it for me if I feel like the writer can’t see beyond his own current cultural situation. I have the same problem with Roth, even though I respect him on so many other levels. But I don’t think he has ever had an evolved enough perspective on the world he wrote about. Saul Bellow’s another. I know he was great, but I’m just not going to do it anymore, because he couldn’t see past his own masculine privileges, and that just doesn’t do it for me.

DM: I feel like everyone needs a list of great writers–alive or dead–that they’re willing to fight if given the chance. You’ve got to just make that promise to yourself.

CL: There are definitely some writers I would call on their shit if it came to that. A lot of the “Super Important Male Novelists of a Certain Age” never used their privileges and talents for much more than making a long argument for their privileges and talents. I find that tremendously boring. Especially if they were writing through the mid twentieth century and couldn’t manage to further empathy for women’s, LGBT or civil rights, at all, not even with one character. What rock were they living under? You know who I’m talking about. Or, I guess it could be debated who belongs on that list, but oh man is it a list.

DM: Do you think you’re starting to develop an author persona through these events, these interviews? You always seem pretty pugnacious, ready to brawl, ready to be rude. I say that as a good thing.

CL: I guess that persona starts to shape itself. But I think that’s just how I am. I’m a liberal from the Bible Belt. I don’t have a problem being controversial.

DM: I don’t want to blur the lines between you and Elyria–we already talked about that–but the urge to disappear from a relationship and from a life is one of Nobody’s central preoccupations. Is that an urge that grips you?

CL: I do feel it. There’s a power in disappearing. You can reinvent yourself when no one knows your history. But my urge isn’t quite the same as Elyria’s. She wants to disappear and not tell anyone. I like to travel alone and not answer emails or make phone calls for days on end, but I like coming home too.

DM: You went on a long trip to New Zealand before you wrote the book. What was your mindset there? Were you just wandering? Or were you doing the Kerouac thing, doggedly collecting material for a road-trip novel?

CL: I went because I wanted to study permaculture and bio-dynamics. I was done with graduate school and unsure what I was supposed to do next and I hate the winter, so I wanted to go to another hemisphere, to some place where I could hitchhike between farms and always be near a coast. New Zealand was really the only place that fit the bill. I was barely writing when I was there. I was working on farms and reading books and hitchhiking all the time. I wrote maybe a single story, five hundred words. It ended up being the original seed for Elyria, but I didn’t think it was a novel at all.

DM: What was it about hitchhiking that called to you?

CL: I didn’t have that much money and I don’t like driving. It seemed like an easy and interesting way to learn about people. And also it just freaked me out and made me uncomfortable, and I thought that kind of stress would be good for me.

DM: Any hitchhiking tips, now that you’ve made it through to the other side?

If you’re a woman and you can somehow team up with a non-intimidating man, make a duo. If you’re a woman alone, Mom-aged women will pick you up and tell you not to hitchhike, that you’re going to get killed by some crazy man. Then a man will pick you up and the thought will cross your mind that he might be that crazy man, even if he seems nice. If you’re a guy alone, people will be afraid of you. But if you look like a couple, people will think it’s sweet, and they’ll also think that you must be okay, since you’re together. Also, a hitchhiking partner helps it be less boring.

DM: For the last few years, while you were writing Nobody, you’ve been a co-owner and co-operator of a B&B in downtown Brooklyn, called 3B. That’s just crazy to me. I’m not sure I have a question about that. It just seems crazy.

CL: It is crazy! I never would have done it on my own. It was a group idea. I was just back from New Zealand, and I was trying to decide if I should stay in New York or not. In the meantime I found this sublet, and the people there were about to start a B&B. They seemed like great people, and I had nothing to do, so I stayed and helped start it. I’ve been there about four-and-a-half years now–I’m actually moving out this week–but that schedule and safety helped me write the novel. I’m a really solitary creature. It was good for me to challenge that a little bit, to learn how to live with people, to build and run a business with six others.

DM: You’re from Mississippi, and you recently wrote a piece for Guernica where you delved into some issues about the contemporary South–religion, LGBT hypocrisy, manners getting in the way of progress–and I wondered, reading your novel, where you think you fit in the Southern literary tradition.

CL: I think anybody who grew up in the South and writes, even if they’re not writing about the region, becomes a Southern writer. Their perspective has been shaped by having to react in a high-intensity environment with an even more radical history. There’s racism, xenophobia, poverty, chauvinism, the religion thing, and LGBT rights these days. Maybe that’s part of why I feel like I need to be a little rude, because I grew up in this culture of pushing everything under the rug and polite-ing around issues that too many people have shitty, reprehensible, ignorant ideas about. It’s part of the reason why progress doesn’t happen anywhere, not just in the South. People don’t say what they really think and what they really feel. They’re too polite or afraid. I always felt like a bit of a weirdo in the South. I haven’t written much set there, but in a lot of ways, Nobody is a Southern novel. It’s about a woman in a rural setting feeling alone and wondering what this life is, what it’s about.

DM: Your writing–fiction and non-fiction–ventures into some emotionally vulnerable territory: Nobody seems to touch a raw nerve with a lot of readers, you wrote for The Atlantic about donating your eggs, a short story of yours that was featured on this site stirs up some uncomfortable body image issues–and I wonder if there’s a piece that you remember as the hardest to write, or the hardest to see published?

CL: Most people think the egg donation article must have been really difficult for me, but it wasn’t. That was just an experience I had. I can take care of myself and write about my experiences. But the Guernica piece, which was about the South and all these issues that I think are so important–that nearly gave me an ulcer. I was writing about a political situation that affects my friends and family. I was pretty much attacking the church I grew up in. It was crucial to me that I wrote that thing as perfectly as I could. It was hard writing about it and hard seeing it published, but once it was out there, I felt good about it. I want to continue working on pieces like that but I have to work up the nerve.

DM: I take it you were raised in a very religious environment?

CL: I grew up in the Methodist Church. It’s not like I was snake handling and speaking in tongues–they were just down the street–but I still take issue with a lot of the inherited ideology. I took that whole world to heart at a young age, and became pretty devout. I wanted to bring people to heaven. I had a more conservative view than even my parents did. The Bible freaked me out at a deep level. I think when you teach children about hell at a young age and they’re listening and reading the Bible and thinking about it, it can get extreme and a little crazy. But so much of it feels so true, and the main thrust of the Gospel is so beautiful, and there’s so much to admire about Jesus’ teachings. It’s easy to be swept up in that and take in all the garbage that got in there along the way.

DM: Do you remember a moment when you started to break away from the faith?

CL: I was going to a lot of church as kid. (No offense to the any church people, although I doubt they’re reading Electric Literature, a well-known heathen site.) As I got to be a teenager, I started seeing all these things you don’t see as a kid, like you can’t be openly gay and be clergy. You can come to church, but you can’t be clergy because they think that part of you is fucked up. To me, that is sick and fearful and anti-human. The rejection of all non-heterosexual identities is just one of the easiest issues to point to, but there are other internal conflicts in the church and in the Bible. The more I saw those the less excited I was about orienting my whole life around a document and an institution that out of sync with me.

DM: Is that religious feeling still a part of you?

CL: I don’t consider myself a Christian anymore. I don’t go to church except for weddings and funerals. I can’t stand passive Christianity. If you just call yourself a Christian, but you’re not grappling with the conflicts, then you’re not doing Christianity or anyone else a favor. You’re just vaguely participating. You’re voting without looking at the ballot.

People who grow up without religion don’t necessarily feel the need to have one as adults or even participate in debates about religion. But I am drawn back into the conversation because it’s such a deep part of my childhood and my family. And I lost this dominant worldview–that I was going to heaven and everyone was coming with me so long as I could get them to accept Jesus as their personal Lord and Savior. I really believed that. I knew Santa was a hoax pretty young but the afterlife, the virgin birth, the death-cheating, gravity-defying Jesus — he was like the original superhero. And people look down on Scientology.

DM: You’re describing a pretty intense faith and a pretty intense abandonment of that faith. Do you feel like you’re still prone to extreme attitudes, beliefs?

CL: I probably am. Writing becomes the new religion, I guess. And reading, learning. Not being passive.