interviews

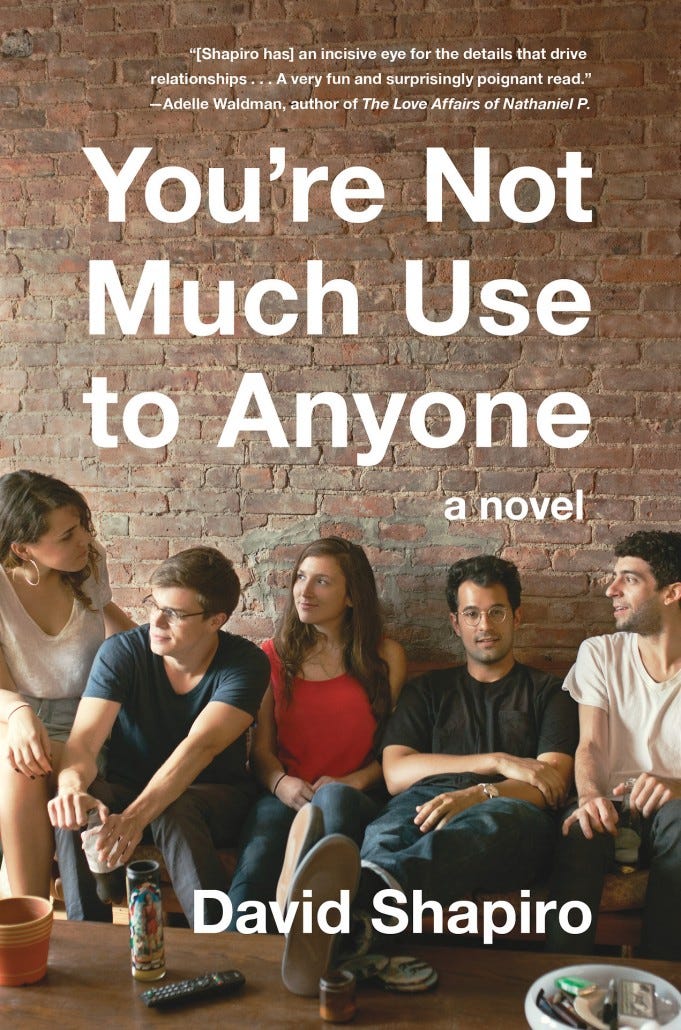

INTERVIEW: David Shapiro, author of You’re Not Much Use to Anyone

by Ari Lipsitz

David Shapiro is the author of You’re Not Much Use To Anyone, a fictionalized account of his immediate post-grad life. After finishing NYU, David started the blog Pitchfork Reviews Reviews, which garnered enough notoriety through its combination of personal vulnerability and social insight that the New York Times interviewed him for it. After shutting down the blog, Shapiro enjoyed a successful freelancing career. He is now ditching it, and writing altogether, for law school.

We spoke on his roof about his book, quitting writing, law school, anonymity — Shapiro is not his real name; he chose a name common enough that it would be tough to Google. In his head, nobody will ever find out about this entire persona. (I get the sensation this is fun for him.) — and how to end a story about a character who hasn’t learned anything.

Ari Lipsitz: So the character is named David. The book calls itself semi-autobiographical. When writing the book, how did you approach the — hold on, what do I call the protagonist? David? You?

David Shapiro: You can say “the character David.”

AL: Okay, how did you approach the character David, in relation to your own self? Were you aware you were writing a character, or was it purely autobiographical? And how are we supposed to approach this character in relation to David-the-author?

DS: It’s so embarrassing to say that it’s me. I guess the character is an exaggerated part of me. To the character, 300 Tumblr followers is the whole world. This is the biggest thing that has or will ever happen to this character. The whole enterprise is so embarrassing.

AL: What’s embarrassing about it?

DS: How much the character cares. It’s not becoming to be so obviously desperate. The character is such a loser. David just wants people to like him in such a desperate and transparent way. It’s embarrassing for it to reflect on me, and even more embarrassing that it has the air of truth.

When I finished writing it, and first sent it to my agent, I sent a really long disclaimer email, saying that he couldn’t talk to anyone about it, and that I wouldn’t talk to him again if he did. I was afraid that when I wrote it, someone would call my parents and have me committed to a mental institution and I would have to explain that there were some parts that were true and some parts that weren’t.

There are things that I would never tell anyone and have never told anyone. People who read it text me or email me, “I really like this part. This part is really funny,” or “This part is really sad.” Then I remember the real-life basis for that part, and I feel so embarrassed to know that another person has read it — that another person knows me that way. People read it and say, “I’ve been friends with you for years, and I learned more about you reading this book for a half hour than I ever have in talking to you.” It’s scary to hear that.

AL: Scared that they think the book is true, or that they think they understand you from it?

DS: I dread the possibility that when I’m 50, someone will read it, and think it’s all true and assess me based on that suspicion. It is, factually, not all true. There are a lot of things that are shifted in time, and a lot of details that people have told me about themselves that I thought would be fitting.

It’s a lot more untrue for all of the other characters. There are things that come out of the mouths of other characters that have bases in real-life people that those people never said.

AL: Many of the characters scan as real individuals. For example, there’s the 14 year-old fashion blogger from Texas — easy enough to pinpoint. But then if you know the right people, you could piece together who the minor characters are. Did you experience any resistance from your friends?

DS: I feel really guilty about it. I feel exploitative. A friend of mine who is the basis for a character asked, “How could you have done this? I never signed up for this. I never thought that you would think of doing something like this.” If someone had written about me as a character in a book the way that I wrote about other people in the book, I don’t know if I could ever look at them or talk to them again. I don’t know if I could ever be in the same room as them again.

I still do worry that they might wake up one morning and be like, “Damn, the cons of being friends with David have really outweighed the pros, fuck that guy.” I guess that’s some part of why I never want to do anything like this book again.

AL: You wrote this when you were 22, as a first-time writer who has stated you’ve read maybe 12 books outside of school. At 26, what is it like grappling with the personal issues of someone who just graduated college?

DS: I tried to take as many of the embarrassing parts out as I could. And I didn’t succeed entirely, or even that much. But yeah, sometimes it’s awkward to talk to my editor about scenes in the book. They are things I thought to myself, wrote, and other people read them, but I still pretend I never thought.

There are intimate romantic scenes in the book i’m mortified to read. I can’t read. Maybe when I’m 50, I’ll be able to read those parts again. But it’s so embarrassing now. I also can’t read anything about the book: I can’t read the blurbs on the back of the book, and I can’t read any of the marketing. One of my publicists told me she would send me a review of the book today, and I told her, “Don’t. I can’t read it.” I don’t like to read anything about the book. I won’t read this interview.

AL: Okay, okay. Is there any avenue in which you think the book was successful?

DS: The best thing about the book is that it’s easy to read, and it’s short. It has propulsion — once you start reading it, you can read it in one sitting. I’m proud that at least I’ve heard it’s readable. I’d rather have written a readable book that’s horrible and embarrassing than a good book you could never get through.

AL: The book can be emotionally vulnerable — it gives the character David room to act petty, jealous, short-sighted, and occasionally even malicious. One of the most poignant parts of the book is when David reconnects with his ex-girlfriend Emma, and shuts off when he hears she is dating someone after moving away. (Favorite line: “Remember when you told me to start my Tumblr? It has 15,000 followers now. How many followers does the mountain man’s Tumblr have? Does he Tumbl all the way down the mountain?”) It doesn’t make him look good — and because he is so similar to you, were you concerned readers would associate you two? You could have written David as a self-congratulatory character.

DS: I wouldn’t know how to write a self-congratulatory character — or be a self-congratulatory person. Everything good that happens to me, I feel guilty about it. I don’t think there would be anything I could do that would make me feel satisfied with myself.

It was hard for the character to understand why the character Emma would leave, rather than stay in New York to hang out with him. But she’s under the same pressure to find a job and do something. But he doesn’t realize it. He’s not considerate in any way — of her or anyone else. He goes through a lot of trying to figure out what he’s trying to do for the next 40 to 60 years of his life. And Emma is doing exactly the same thing. And they never talk about it.

He never shares any anxiety. He never has any meaningful conversation with her about anything but their relationship. They never talked to each other like adults, or what I imagine adults talk about. But he doesn’t ever share anything. He’s lying or misrepresenting to everyone about what he does, and how satisfied he is about what he does. He never gives her an opportunity to explain she’s dealing with exactly the same thing. And she assumes he isn’t because he never says, “I have a super shitty job.”

AL: The ending is interesting. It feels like it tries to resolve a tension, but gets annoyed with itself and gives up.

DS: What’s the ending of a book supposed to be? The character learns something? There’s a coming of age? That feels false. I haven’t come of age yet. I don’t have any wisdom to share on almost any subject. It felt stilted to write an ending with a strong resolution, or even any resolution. I’m listening to the first Clap Your Hands Say Yeah Album. The last song just ends in the middle, as opposed to the volume going down and fading out. It leaves you wanting more in a way.

What’s the phrase: it’s better to burn out than fade away? I think it’s better to completely extinguish yourself.

AL: And the major catharsis of the book is a little fizzled. Throughout the whole book, David is preoccupied by the supposed intrigue and social superiority of Pitchfork writers, and it motivates him to start the blog. But the major catharsis — Pitchfork writers are just typical bozos like him — is undercut quickly.

DS: Yeah, that’s a really short part: Realizing that Pitchfork writers are just like other people around the same age, who live around the same areas, who sleep with approximately the same women, who aren’t poor but don’t have that much money — who are basically the same. It’s kind of elided.

AL: The whole book is elided, kind of. What was the idea behind withholding that catharsis?

DS: There’s a climactic sex scene wherein the real focus is getting McDonald’s after sex. The highlight of the sex scene is he gets a McFish. Sometimes a profound realization, when it happens in real life, isn’t handed to you with tablets on Mount Sinai. You just figure it out eventually. When I was emailing my agent about the book, I told him my idea. He said, “That sounds interesting. What’s the conflict?” I wrote back, “What do you mean by conflict? Like a scheduling conflict?” It doesn’t come naturally to think of it that way.

AL: The book ends with David deciding to commit to law school. But it’s ambivalent — his pushy Israeli parents are uncertain if he really wants it, and he doesn’t know how to communicate with them. Does the book have an opinion on David’s future — if it’s a good thing he’s quitting?

DS: I don’t know if the book can have an opinion exactly, but it seems the narrator just wants to figure something/anything out — so law school, medical school, engineering school, moving to The Outback and raising kangaroos — just anything would be sick. The narrator loves his parents and wishes they could also be 22 year-olds who thought of themselves as failures and had graduated into a hopeless economy so they could understand how the narrator’s first and only taste of success might feel.

But at the same time, he understands that they are adults whose job is parenting, which sometimes entails forcing the kid to make bright decisions that appear to crush his dreams at the time but he will come to appreciate later. Maybe the book should have been called You’ll Understand When You’re Older, David.

AL: And now you’re 26 and in law school. Are you truly done writing?

DS: I’m retired.

AL: Just from books, or from any writing?

DS: I think I’ll do reporting if it’s something I’m interested in. Before I went to school, I worked as a blogger for a few months. There were parts of it I really liked. But as a blogger, you have to cover stuff you’re not personally interested in, if only because there’s a demand for constant content. So I ended up doing some stuff that felt perfunctory. And now, I feel like my writing is better because I’m covering things I’m enthusiastic about all the time.

But once I start working, I won’t write anymore.

AL: And you’re totally fine with that? You’ve been called a talented voice. You got interviewed in the Times. You’ve been published everywhere. You’re okay with retiring?

DS: I look forward to it. I really liked writing when I was 21 or 22. Every since then, it’s seemed like more of a job. I wrote the book when I was 22. So it came at a point when I was still writing in a way I was proud of. Not that I’m not proud now.

AL: You aggressively bisect your lives. (At the bar, when a law firm friend approached him, he furtively admitted the existence of his book and begged the friend not to tell anyone.) Do you think of yourself as David S. the law student, or David Shapiro? Is there a difference?

DS: I think I’m both, although the writing/reporting I’ve done has sometimes been helpful in terms of training me to ask questions in a way that’s helpful in a legal setting. I think I am really both, although would like to be more David S. And less David Shapiro as I get older.

AL: How long will you keep up the separation?

DS: Until I kill off David Shapiro right after this book comes out.

AL: You’ve been open about your unequivocal love of law school. Do you think that young people are missing something when they commit to creative careers, as opposed to a professional lifestyle?

DS: I don’t know if people are missing something about law school — I guess I just think people are focusing on the bad parts without considering the great parts. Law school gave me the chance to deal with a million fascinating and fundamentally irresolvable problems. After a few weeks in law school, I felt like, for the first time, I was reaching something like my cognitive potential. I felt like I was doing what I was put on this planet to do.

AL: I guess I believe that you love it. But I also believe you want to love it, in a way.

DS: It’s like someone both simultaneously believing that their husband is the love of their life, and wanting to believe their husband is the love of their life because it’s convenient based on the choices they’ve made. I both believe and want to believe it.