interviews

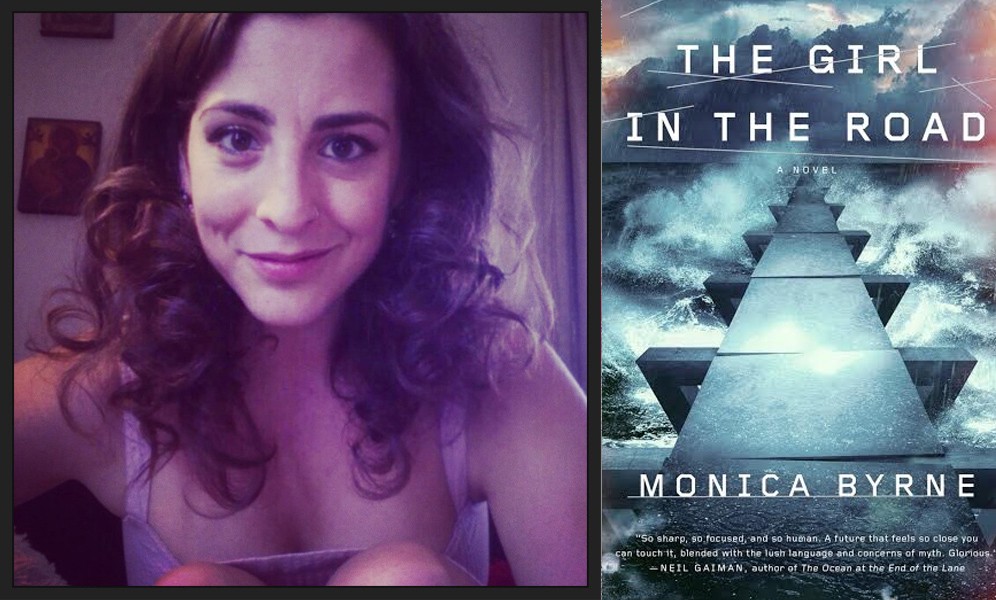

INTERVIEW: Monica Byrne, author of The Girl in the Road

Monica Byrne is a writer based in Durham, North Carolina, where she’s a playwright in residence at Little Green Pig Theatrical Concern. Byrne has published essays and short stories in The Atlantic, Virginia Quarterly Review, WIRED, The Baffler, Glimmer Train, and The Rumpus, among others. She’s traveled widely to countries including Morocco, Italy, Ethiopia, Trinidad, India, Fiji, Costa Rica, Iran, and the Philippines, and plans to travel in many more. She holds degrees in biochemistry from Wellesley and MIT. This summer she will teach at the Shared Worlds teen SF/F writing camp.

Her first, critically acclaimed novel, The Girl in the Road, was published by Penguin Random House in 2014, with the trade paperback edition out today.

Set about 50 years in the future, The Girl in the Road is a complex and twisty narrative that chronicles the paths of Meena in India and Mariama in Africa. As the novel opens, Meena is in desperate headlong flight, enemies in pursuit, and Mariama must make a trek across the Sahara. Central to the novel is The Trail, an “energy harvesting” bridge that spans the Arabian Sea. It’s an audacious creation by the author, but nothing compared to the bold portrayals of Meena and Mariama, whose fates, as they say, are linked, although not in predictable ways. In addition to strong characterization and a unique premise, The Girl in the Road teems with rich (but not overwhelming) description that makes the future seem both tactile and lived-in.

I interviewed Byrne via email about the novel, and her travels.

Jeff VanderMeer: How do you personally internalize research, and what does “research” entail for you?

Monica Byrne: I’m a pleasure-seeker. That’s basically it. When I try to explain what creative research is like, people say, “So you just get to have fun?” and I’m like, “Yeah, and then I write about it.” Even doing calculations for The Girl in the Road was fun because I knew it would help me tell a more true story. When I was in grad school for geochemistry, I was supposed to be learning things to pass tests or design experiments. But what I really wanted to do was learn things so I could fasten them upon a much larger tapestry of meaning.

As soon as I’m not having fun, I know I’m off the path — trying to satisfy some external notion of what’s good or worthwhile, instead of thrilling myself. Pleasure is my magnetic north.

JV: Did anyone ever tell you as a writer to “just drop the reader right into the action and let them adjust”?

MB: Haha, no, but I do remember reviewers on the Online Writing Workshop always telling each other that they needed to cut the first several pages of their story. I thought, “I’ll just cut the part of my career where anyone needs to tell me that.”

JV: What is the importance of a name to identity? What do names signify to you?

MB: Huge! I can’t proceed without the right name. It just feels bad, like I’m trying to walk a dog that doesn’t want to walk, so she goes slack and I end up dragging her. Sometimes I have to “audition” a name for days or even weeks to see if it’s a right fit. If I start referring to a character or place name in moments of unthinking, then I know it’s right.

JV: The loss of a parent in a novel can be trite, not felt on the page. But in The Girl In the Road, this loss is important and it is deeply felt. Did that develop naturally?

MB: I hope it is, because that was the central event of my young life. I lost my mother as a functional parent when I was seven, and she died when I was twenty. Processing that loss, first as a child, then as a teenager, then as a twenty something, became the blueprint for The Girl in the Road.

I still miss her constantly. I dream about her all the time. I love and am so proud of The Girl in the Road, but I’d have never written it if she hadn’t died. That makes it all bittersweet.

JV: There also seems to be a theme of betrayal in the novel. Could you speak to this?

MB: I think that, when one grows up with massive loss, one way of coping is to form very fierce and passionate relationships. It’s my seven-year-old self saying “Don’t leave! (I get to leave.) But you don’t!” And if they do, even kindly, it’s perceived as abandonment, and the seven-year-old goes supernova.

Unfortunately, that’s how I perceived every breakup in my twenties, regardless of what actually happened. Every separation echoed the Alpha Separation. So each of the sunderings in The Girl in the Road are representative of how I’ve received various relationships’ ends — basically, as betrayals.

JV: You’re a scientist in addition to a writer. I felt the milieu of your novel quite strongly, but I didn’t feel as if it was that science-driven, which I mean in a good way. Yes, there’s advanced tech and all of that, but it exists at the proper level in the narrative. Was it always that way in your rough drafts?

MB: Yes. I never wanted tech to take center stage in the book; I wanted it to serve a supporting background role, as it does in my daily life. Plus, that spared me the agony of having to, say, actually figure out how a kiln works. I could just say, “Simple sugars! They break down and rearrange! In cube form, because that’s the only shape we can manage in 2068!”

I like thinking about how technology is both revolutionary and rudimentary at the same time. In college, I used Napster, which was like an unthinkable treasure trove at the time, and now it seems like banging rocks together. Now, I tell my iPhone to play a song, but I have to speak very slowly and clearly and Siri still gets confused and directs me to the nearest Planned Parenthood instead. Technology has to work imperfectly to seem real.

JV: And in what ways is your science background a plus or a liability in writing fiction? The Trail is a fascinating creation but it’s largely because of the human element that it comes to life.

MB: It was definitely a plus. I had the training to at least approach all of my scientific research topics — climate change, metallic hydrogen, trail mooring, and so on. I also asked a few experts to weigh in, like my friend Stefan Gary, who’s a research oceanographer in Scotland. He was able to read the manuscript and tell me immediately what was and wasn’t plausible.

I’ve always been anticipating a reader who’ll stand up at a convention and say, Look, the Trail can’t work, here are my calculations. No one has yet! I want to thump my chest and be all MIT, WHAT but I bet someone’s working on it. They’re out there. Scheming.

JV: Would it be an accurate reading of your novel to say that you believe that we won’t see progress on matters of class in the future? (In any cultural context.)

MB: Progress, maybe, but not resolution. It seems to me that in any capitalist society, class will still be a tribal marker, even if all other distinctions — sex, gender, race — fall away. But keep in mind that the farthest we’re seeing ahead here is 2068. That’s nothing. The problems of 2068 are just the problems of 2015, writ large.

JV: Diversity in fiction is a topic of frequent conversation and debate. Your novel doesn’t feature any major white characters. How do think of diversity in terms of your fiction and what do you think it means in terms of the audience for your fiction?

MB: It doesn’t feature any white characters at all, actually, and that was very deliberate. The novel is set in India and Africa, so there are comparatively not many white people there; but still, every time I introduced an incidental character, because I was raised in a white supremacy, my instinct was to make it a white man. And in each case I asked myself, “Is there any reason it has to be?” and there’s never an answer other than “it feels right,” which is the smooth-talking patriarchy in a double-breasted suit. So, fuck him. The doctor in South Sudan? African woman. The tourists in Mumbai? Chinese. And so on.

Not seeing my sex and gender represented in fiction definitely affected me when I first sat down to write my own stories.

Not seeing my sex and gender represented in fiction definitely affected me when I first sat down to write my own stories. I couldn’t really think of a female hero because I’d been raised on Frodo, Muad’Dib, and so on. So I just try to remember that in all dimensions: writing the world I both see and want to see, and so, helping to create it. And then, that attracts like minds. I want to cultivate a community of fans who want to learn from each other.

JV: Do you think a writer can write accurately about a place they haven’t experienced first-hand? Where lies the lack in that case?

MB: Hmmm. Depends on what you mean by “accurate.” I was really pleased when my agent assumed I’d been to all the places I described in The Girl in the Road. I haven’t. I’ve been to Ethiopia and Kerala, but not Dakar, Nouakchott, or downtown Mumbai. I looked at a hundred pictures, though, and watched a shitload of YouTube videos. (Protip: want to get a feel for a city? YouTube search “[city] taxi” or “streets of [city]” and videos will come up, guaranteed.) I tried to be as accurate as possible in my depictions, incorporating what I saw, and not contradicting anything I saw. For example, the description of Bamako as “a windy city sprawled on the banks of a river the color of steel” came straight from my impression of three seconds of a YouTube video.

But would a person from Bamako feel the same way? I don’t know.

The funny thing is, I’ve also physically been to places that I don’t feel like I could describe at all. The best example of this was the Underground River in Sabang, in the Philippines. I’d been so excited about it because I love river caves, but the trip was overdeveloped to death: uniformed personnel taking my picture so they could sell it to me later, the boatman talking nonstop about cave formations that looked like dicks, and so on. Halfway through, I just shut down. It was like I was gliding through a simulation. I was physically in the cave and yet so mad that I couldn’t see the cave. If I wrote anything truthful about that experience, it would be about fury and blindness. (And maybe entitlement, ha ha.)

JV: You’ve traveled a lot in the last year and along the way you’ve written with passion and precision about places like Iran that most Americans perceive in a very particular and narrow way. Is seeing the whole, so to speak, simply a matter of unlatching our impressions of a government or regime from the actual people who live in a country, or is it more complex than that?

MB: Oh, yes, the government and people are worlds apart. Just as an example, Iranian people generally have very warm feelings toward American people. You’d never know that from the hostility between our governments.

After having been there, it’s actually hard for me to remember what Iran is “supposed to be like” in the American imagination. Because all I remember is the kindness of the people, the staggering natural and architectural beauty, the closeness of families, the reverence for artists. The feeling of being in love with a kingly presence, ancient cypresses, golden dust.

But you know how astronauts say, “Once you see the Earth from above, you see all our divisions are meaningless, blah blah blah”? And I’m like, well, we’d love to, comrade, but that opportunity isn’t available to us. In the same way, it’s not possible to send every American to Iran to show them what an extraordinary place it is. So I just try to say it every chance I get, and hope it does some good.

JV: Does your travel directly inspire your fiction writing? Anything from your recent travels that stuck in your mind in particular from the perspective of narrative?

MB: Yes. I travel to write and I write to travel. Often, I travel to a new place without knowing why, only that I feel drawn there. That’s what happened with both Belize and Iran. Once I got there, I found what it is that’d been calling me — in Belize, the cave in Cayo where my next novel is set; and in Iran, the zurkhaneh in Yazd that’s become the basis for a new fictional religion.

The zurkhaneh has no Western analog that I know — it’s like a sacred gym where men perform ritual feats of strength in devotion to Ali, the second Shia imam. And…like…I can’t even describe how I felt when I went there for the first time. I was in total rapture. When I came out I wanted to scream and shout and pound my hands against the wall to get out all the energy that had accumulated in my body. I watch YouTube videos and turn up the volume and go into a frenzy. I need to go back to Iran for a thousand reasons, but I’d go back just for the zurkhaneh and nothing else.

JV: What’s your favorite word?

MB: Sanovy. It’s in The Left Hand of Darkness — as in, “the Sanovy teachings” — and then never mentioned again. But it struck me as the loveliest word I’d ever read, and I even named my own language after it. N’phora d’emwaia. Hanalelaca emwitia.