interviews

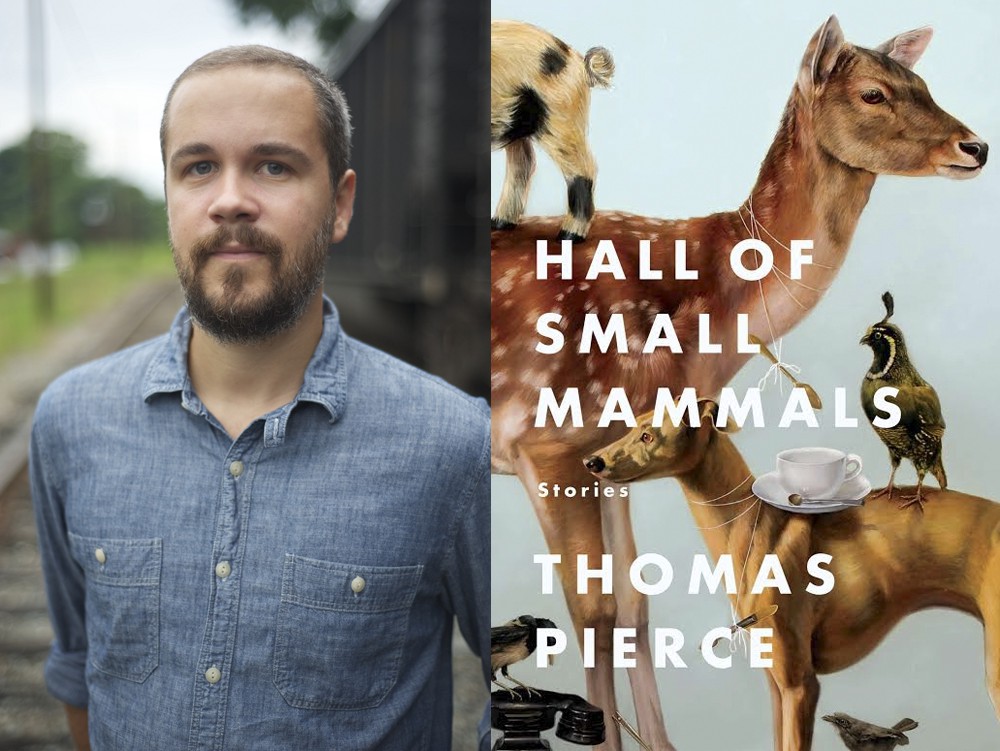

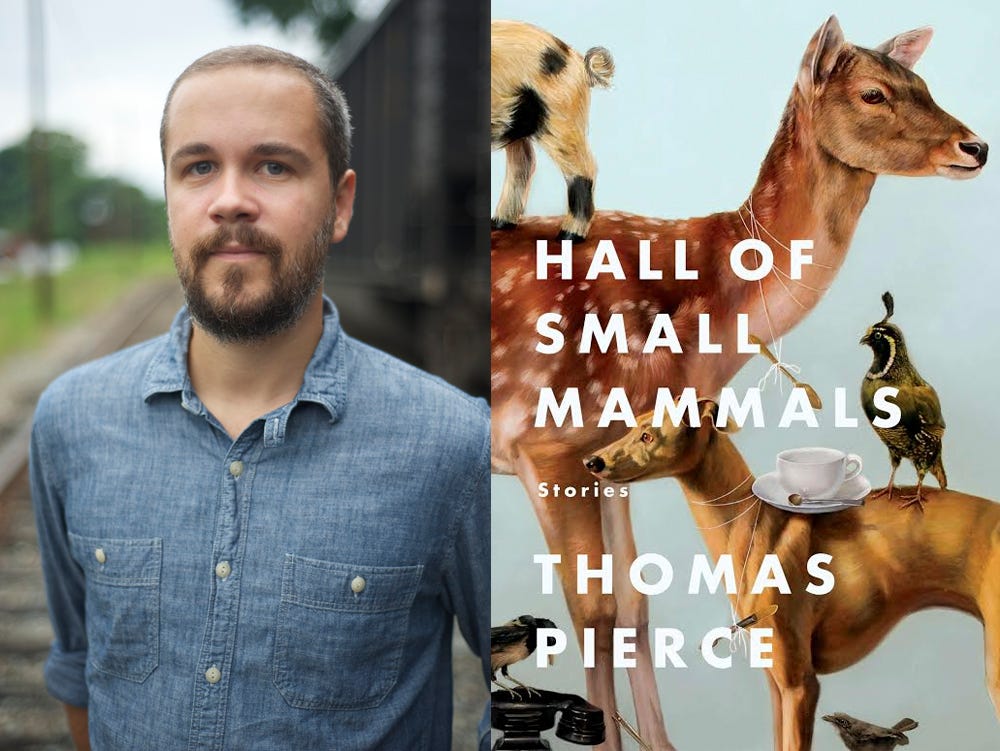

INTERVIEW: Thomas Pierce, author of Hall of Small Mammals

by Diane Cook

This summer, I started following Thomas Pierce on Twitter. I’d admired the stories he’d published in The New Yorker, and I’d begun to hear about his forthcoming story collection, Hall of Small Mammals. But I knew nothing else about him. Then one day this fall, I happened to see this tweet of his:

all these years after leaving npr i still sometimes have director nightmares: a lost story, dead air, the clock, the clock, the clock!

In the grand scheme, there are very few people in the world who can truly understand the particular stress of producing live radio and who will be plagued by fever dreams long past their time doing it. Even fewer of those have written books, let alone forthcoming debut short story collections. And maybe just two people from this already small pool have an interest in looking at humans through some kind of natural world lens. (Hint: that would be me and Thomas. I dare you to find another.) I think a lot about how my past as a producer for public radio’s This American Life influenced my writing and I was curious how his experience at NPR had shaped him. So I contacted him to see if he’d be game to talk about writing and our pasts in radio and how that all mixes together. This was before either of our books had come out. But once we began to make time for a conversation Thomas’s book was on the very near horizon, so it made sense to focus in on it. Plus, it’s really great.

Hall of Small Mammals may be dotted with mysterious creaturely “others” like a dwarf wooly mammoth, unidentifiable skulls, or invisible particles, but it is overflowing with troubled, searching, tender people, or “human animals” as one story slyly calls them, reminding us where we come from. The stories create familiar worlds and cast a fog of strangeness over them. They are compassionate portrayals of characters at odds and at crossroads, looking for answers in what is still mysterious about the world and about us. And the stories have a heady, imaginative sheen over them: what if the woman you loved, loved someone else in her dreams? How would you care for a creature that was last alive before the last ice age? What if you knew the deepest feelings of the people you’ve laughed at online?

As I read Hall of Small Mammals, I would begin to feel as though I knew these characters, only to be totally surprised by them. As though the book was telling me that no matter how common our lives may seem, there is something unpredictable in our hearts and minds, and while yes, that can prompt us to be our worst selves, it can also bring out our best, or, at least the best we can manage in the moment.

Thomas and I emailed back and forth about his book, writing, our own fascinations and how radio landed us here.

[Editor’s note: Read a story from Thomas Pierce’s Hall of Small Mammals here, and a story from Diane Cook’s Man V. Nature here.]

Diane Cook: In the stories that make up a bulk of Hall of Small Mammals, the characters have some encounter with the natural world — a creature, a skull, a theoretical particle. It’d be easy to say these stories are intersecting with the wild world but to me these natural items and ideas seemed more about the unknown and mysterious than a tangible thing we are face to face with. Or rather, the stories chronicle the characters’ quests to know what we don’t yet know, in the grand scheme and in the deeply personal realm. The characters are wanderers even if only in mind and imagination. Did you approach writing these stories with a quest of your own? An intellectual or creative project? How did the themes of the stories reveal themselves?

Thomas Pierce: That’s an interesting way to frame a story, as a quest. I do often think that I want my stories to seek. I want them to be after something. Even if the action is somewhat static at any given moment, I want the reader to have a palpable sense that the story itself is hungry and full of questions. This approach isn’t really particular to this collection. Maybe that’s more like a life-long creative project. Maybe it’s my quest.

I’m not sure the stories’ themes have fully revealed themselves to me yet. I’m joking. Sort of. I do know that I was preoccupied with certain ideas and questions at the time of writing, and maybe this amounts to the same thing. One of my preoccupations was — and is — the trouble that arises as we try to explain the world to ourselves, especially in moments when we are forced to incorporate new, more complex information into our thinking. The collisions with the natural world that occur in the book are, as you suggest, manifestations of the mysterious and the unknown. The fossils, the creatures, the particles — they are disruptions in these characters’ lives. They keep the characters from being too lazy in their thinking, from clinging too firmly to a particular perspective on a relationship or on existence itself.

DC: As I was reading I thought a possible subtitle for the book could be Scenes from the Pop-Yop or something to that effect. The fictional ice cream chain makes many appearances, and occasionally seems to connect characters from certain stories together, or give the appearance of connection. It makes a potentially boundless world of a story collection seem intimate, like all these people live in a town, county, region. And their lives are all circling one another though they may never meet. It doesn’t feel like a linked collection, yet reading it, I felt I’d walked into a familiar place but with realistic distance between people, the way it is in life. Do the stories come together for you in more ways than thematically?

TP: Scenes from the Pop-Yop — I love that! Yes, I didn’t set out to write a collection of stories linked in the traditional sense. They don’t all take place in the same town. One or two characters appear in multiple stories, but in my head they all belong to the same universe. It’s a universe a few inches to the left of this one, perhaps, but I aim for consistency within that world. The characters might not know each other personally or ever interact with one another, but I’d like to think they could, by chance, all wind up on different aisles of the same grocery store one Saturday morning.

The stories are connected but in subtle ways. One story does not depend on another in any vital way. The truth is, I’ve always enjoyed creating alternate but recognizable worlds. I remember writing a couple of stories in college and feeling far too pleased with myself for making references in each to a particular brand of spreadsheet software that I’d invented. It was called Dynamite. (With Dynamite, you can explode your charts and graphs!) I’d be hard-pressed to name something more mundane and boring than spreadsheet software, and so I’m not sure what it says about me that I feel the need to create my own version of it. If I’m writing a story about movies, I’ll make up a few of my own. If I’m writing a story about mammoths, I’ll invent my own species.

That might help to explain Pop-Yop, the soft-serve ice cream franchise that appears in the book. Pop-Yop is the place you see advertised every fifteen exits or so on the interstate. It’s delicious and popular. It’s how we try to tame the world. We Pop-Yop it. You land in a new city and you don’t know where you’re going, and then you see a Pop-Yop, and you say, Oh thank God, they’ve got a Pop-Yop. Bread Island functions, in some ways, as Pop-Yop’s antithesis. Bread Island is like a fountain of strangeness and mystery. We’ve cracked open the earth on Bread Island — with a mining operation, with a mammoth excavation — and unleashed all sorts of craziness.

These elements do help to unify the stories in this book, but honestly I wouldn’t be surprised if they show up again, in future stories. I’m not done writing about Bread Island, I’ll say that much.

DC: Is that how you knew you had a viable book of stories?

TP: I wasn’t thinking about a collection, really, until my agent pointed out that I was close to having one. Until that point, I’d been so focused on the individual stories, but when I went back and looked, I realized she was right. The stories I’d been writing over the last few years belonged together. They were powered by the same engine.

DC: So, I Googled you. And there is this other Thomas Pierce who seems to be this socialite guy about town in NY getting his picture taken with fancy ladies, he in a fancy suit. And there are others. It made me think of the side affects of what happens in the wonderful story “The Real Alan Gass” where the wife’s confession that she is married to another man in her dreaming life sends the narrator on a surprising search for the real life version of her dream husband. Do you think of doppelgangers or of the ways we connect to the people wandering around with pieces of our own identity, namely our names? Or about the stranger ways we connect to one another?

TP: Oh, but I am that socialite! And I hardly ever take off my fancy suit. Not even in the shower. I’m wearing it right now. It’s got baby food all over it — and dog hair.

I’ll go ahead and admit to you (and the world) that I’m signed up for Google Alerts, so anytime my name — or some variation of it — is in the news, I get an email. The vast, vast majority of the articles aren’t about me, thank God. They are about other Thomas Pierces. I think I could probably fix this somehow — by feeding Google more information — but I’ve come to enjoy the alerts. Most of the articles concern one of three things: an arrest, a death, or an award. Lots of Thomas Pierces in jail right now, as it turns out. I got an alert recently about a particular Thomas Pierce serving a multi-millennial prison sentence. Multi-millennial! I forget what he did — I’m not sure I want to remember — but it earned him so many consecutive life sentences that if he was immortal he’d be in jail until the year 4014 or something like that.

DC: I’m going to guess he did something very bad.

Speaking of bad behavior, one of the things that struck me in your stories is how when your characters struggle between right and wrong, right wins out a good amount. In the story we just mentioned, “The Real Alan Gass,” the narrator is offered the chance to do something bad (though understandable) but doesn’t in the end. And in “Grasshopper Kings” the dad begins to get wrapped up in a cultish sense of belonging but eventually comes to the rational side. There is something deeply decent about your characters. Is there a question about behavior you were investigating, and were you ever surprised by where your writing and characters ended up?

TP: That’s interesting. Certainly there are characters who’ve made mistakes and regrettable decisions in their lives, but I think you’re onto something here in that these generally aren’t stories about people doing the “wrong” thing. But then again, I wouldn’t necessarily say they’re doing the “right” thing either. I might be that I have a little trouble with the right/wrong duality. At the risk of coming across like some sophomore business major in the back row of his mandatory ethics class, I do wonder if the not-wrong thing necessarily equals the right thing (except in the rather limited sense that not committing a wrong contains an inherent rightness). If you choose not to do the wrong thing, you’re still left with a wide spectrum of possible behavior, much of which is not exactly good or bad. Anyway, I’m not sure I set out to specifically investigate this question of human behavior. It could be that the characters are basically decent because I want to believe most of us are. Or it could be that I’m simply more interested in people who want to do right but who aren’t exactly sure what that entails in every situation.

DC: Yes, the ambiguity is there, and certainly all the characters aren’t always acting decent. But when they are it feels like a real line in the sand. In “The Real Alan Gass” the protagonist does, over the course of the story, many things that really violate some kind of trust. He goes far in one direction, but it’s here — when given the opportunity to alter his wife’s most private mental space — he comes to his senses, as though waking from a dream of his own. Did I want him to try? I don’t know. Part of me did and part of me hoped he wouldn’t. I think that’s why I liked the story so much — as a reader I too was at odds with what was happening. I became very involved in this man’s life and particular heartbreak. It’s one of the things I so admired about all of the stories. In the midst of them I felt like I could look around convinced I was so close to living, breathing folks that I might reach out and touch them.

TP: That’s very nice to hear. Now of course I’m curious to know how you see our own book in these terms because there are quite a few characters who do something that I’m tempted to call “wrong.” I’m thinking of Phil in “Man V. Nature,” a man who, among other things, steals food from his friends’ pockets as they waste away in a small life raft; or of the narrator in “The Way the End of Days Should Be,” who’s living out an end-of-the-world flood in his mansion and who refuses to aid almost everyone who shows up at the door. They have their reasons for doing what they do. They aren’t doing wrong in a vacuum. These characters, and others, are in dire, life-threatening situations, and I never quite blame them for their actions. I feel like I might be one of them if put in that spot. The choices they make are rarely admirable but they’re almost always believable, honest, and maybe even rational too. What led you to write about what I’ll somewhat reductively call “wrong-doers?” That is, about people in situations where there’s more overlap between what’s rational and what’s wrong?

DC: One thread of my book is concerned with survival. We tend to applaud survival but it can be a pretty ugly endeavor — the things we do to save ourselves can seem cruel but can also be so understandable that they’re heartbreaking. I’m fascinated by how messy life gets when our baser instincts are pressured to the surface, and how often they lead to conflict with other people, even loved ones. So, while I also don’t believe in the reductive right and wrong — and don’t see my characters as wrong-doers either — maybe I’m lacking inspiring words for the conflict between the individual and all others. In my real life I’m liberal and also loyal. But in my fiction I’m puzzling through our responsibility to one another.

In your stories, many of the characters want to connect with something beyond their own scope of being. Is there some motivation you think your characters share? Why do your characters look to the natural world for what feels like surprise or purpose or meaning?

TP: That’s a great question. In the broadest sense of course, the natural world encompasses everything in the material universe. It’s everything we can see and observe. It’s us. Don’t worry, this is not me saying that ipso facto we have no other place to search. I only point this out because I think many of these characters are in search of little glimpses behind the material curtain, and their search is prompted by that which is seemingly unexplainable (or unnatural): a deformed and questionably evil skull, a resurrected mammoth, a husband who only appears in the world of a woman’s dreams.

I think that we humans are full of contrary impulses. On the one hand, we want to know everything there is to know. We want all the answers. But on the other hand, I suspect we don’t want that at all. I think we require mystery and even thrive on it. I think a small part of us wants the universe to remain just outside of our understanding, and all signs up to this point indicate that the universe will continue to oblige us in this regard. I was reading the other day about a theory that reality is in fact a hologram, that we’re actually just bits of 2-D information encoded along the rim of the universe. (This is not a crackpot theory, by the way.) Suppose we prove it’s true. No doubt, for some, this would be a distressing discovery. Some people would reject it because it doesn’t mesh with what they already believe. Somebody else might choose it as their new belief. Others might try and incorporate it somehow into an existing belief. I can imagine some preacher out there suggesting to his congregation that the 2-D information is the language of God and that the rim of the universe is the iris of God’s eye. So be it. My point is that new discoveries don’t have to squash our most basic questions. I actually think they can revive our questions. They invite us to engage with the bottomless mystery of our own existence.

DC: I found your writing wonderfully unfussy and the dialogue perfectly natural. Which did not surprise me. You used to be a radio producer for NPR. I wonder if any person who ever wrote for or produced radio is even capable of overwriting? Writing for the ear has to be clear and directional. I think radio writers really appreciate simple construction because we’ve seen how well it works. Has radio influenced your writing at all?

TP: Thanks! And that certainly applies to you too, as a fellow recovering radio producer. Your writing never gets in the way of itself. Writing for radio really does train you to write economically. You have to get to the story with as little preamble as possible. No time to dither. After all, you might only have a few minutes to tell your story. I think writing for radio also made me very aware of “audience.” I don’t write in order to please an audience and I don’t typically think too much about whether a story is capable of finding one, but when I’m revising, I do think about the potential readers, who have taken time away from their lives to sit with me for a moment.

DC: That’s a great point — You have to get to the story with as little preamble as possible. It’s something I do a lot but I’d not thought of it like that before, or, I hadn’t thought that the way I establish a fabulist or fantastic world — where I get the rules of the world down immediately — actually has some roots in my radio days. The goals are the same though — you don’t want to lose your audience, whether it’s their attention or their trust in you.

TP: Yes, exactly, and you do that really well, by the way, dropping us right into a world.

I also think working in radio taught me to finish projects and to be a more disciplined writer. When you’re working on a deadline — and working toward a show week after week — you can’t really give up. You have to make the best of the tape you have. I used to give up on stories too fast. I had so many fragments and partial stories that never amounted to much. Now I try to finish every short story even if, halfway through, I’ve begun to suspect it’s terrible and unusable. I have plenty of awful stories that I’ll never send out, but I think generally it’s good to try and finish them no matter what.

Were you writing fiction before you worked at This American Life? I’m curious if you’ve noticed any changes in your style or in your patterns as a writer.

DC: I wrote fiction in college but then stopped. I had started listening to the radio. Got swept up in voices and in nonfiction. The truth seemed nobler than my (then) silly ideas. But really, I think I just got stuck with fiction and didn’t know where to go with it. I had raw skills and no purpose. Working at This American Life taught me how to work with writing and also how to be a working writer. I got a lot of practice at structuring and identifying what the story was in any given project. But eventually, I started to feel the boundaries of journalism, of telling the truth. I wanted to explore more than what had already happened in the world, or what was happening at that moment. I wanted to think and dream beyond that.

Is there something about your subject matter and interests that drove you from radio? An obsession or fascination that could never be scratched by radio…or you think can’t be scratched? What does fiction do that journalism can’t?

TP: That pretty much sums up my own experience, too. I wrote fiction in college and then stopped — or very nearly stopped — after I started working in radio. The way you describe wanting to explore more than what’s already happened or is happening in the world, I can definitely relate to that. I think a lot of what interests me could not be classified as newsworthy. I feel like I can put more of myself into my fiction. I don’t mean autobiographically but emotionally and philosophically. My fiction might be a better representation of who I am than my work in the news. Still, I do miss radio. I miss the feeling of being a part of a show. It’s almost like playing in an orchestra. I miss the collaboration and the teamwork of putting on a show each week. I also miss the adrenaline of being live on the air. Maybe I’m not finished with radio yet. What about you? Can I just throw back this question to you?

DC: Yes, that’s exactly it. My interests didn’t always feel newsworthy. And more, I wasn’t particularly interesting as a journalist. You know, I left radio in 2007 and the radio culture I left behind felt limited to me, or at least, limiting. And that hadn’t really changed in the seven years since. BUT, this year, suddenly (it feels sudden though of course nothing is) audio storytelling feels reborn in the podcast realm. It’s exciting and boundless and risky in the best ways. Obviously my impulse to innovate led me elsewhere, and if I’d been truly suited to radio journalism I probably would have attempted to innovate from within. But it was a funny experience to launch my book the same week as my former (and incredible) colleagues launched Serial. My new chosen medium felt old and yellowed next to shiny new podcasts. That said, it still feels dominated by true stories and I just don’t have much interest in that. I love reading nonfiction and listening to it, but don’t want to be held responsible for it any longer. I don’t think I’d ever return to that kind of journalism, but I could return to audio if it had to do with fiction or the art of writing.

And what about you, what’s next for you? A return to Bread Island?

TP: Ticket booked. I’ve got some new short stories that I hope to place soon, but mostly I’m working on two longer projects, one of which is a novel due to my publisher at the end of the year. But, hey, if you have an idea for a shiny new podcast that involves fiction and maybe even a little journalism, sign me up. I’ll be your east coast bureau. Almost True Stories, we could call it. If it’s a big hit, people will know this is where it all began, right here in this interview.