Books & Culture

It’s Okay to Talk to Me When I’m Trying to Read

Maybe preserving public interaction is more important than not being bothered

In July of 1964, at a restaurant on lower Fifth Avenue, a woman in a black dress and pearl necklace rose from her table, where she was seated alone. She approached a man who was also seated alone, reading the paper, and ordered him to join her. He did, flustered, and she gazed at him in a way that was, according to an observer, “possessive, but good-humored.” They began to talk, and he began to relax. They hadn’t been together for more than a few minutes when the head waiter came to them and ordered the man to go back to his own table. The woman looked up at him, annoyed, and said, “Who do you think you are?” and the head waiter told her firmly but politely to go home.

Maeve Brennan recorded this entire encounter from a table not far away, describing the man as the woman’s “flattered captive.” Her account of the incident was part of her New Yorker series written under the pen name “Long-Winded Lady,” which recorded dozens of small, insightful non-events around the city. She left the restaurant thinking about the incident and the head waiter, his firm insistence on proper behavior, on public encounters in public spaces. The head waiter’s behavior seems like an overreaction, borderline rude. If the man and woman’s roles were reversed, would it have played out differently?

Recently, I saw a Twitter thread that began with someone’s suggestion for “performance art where person sits down in a public location, picks up a book, reads, and never looks at their cellphone.” One of the replies to the tweet (it’s now been deleted) was that the person doing it would have to be a man, because if it was a woman sitting alone and reading, a man would come up to her and try to talk to her, and then she would have to pretend to be on her phone anyway, to make him go away.

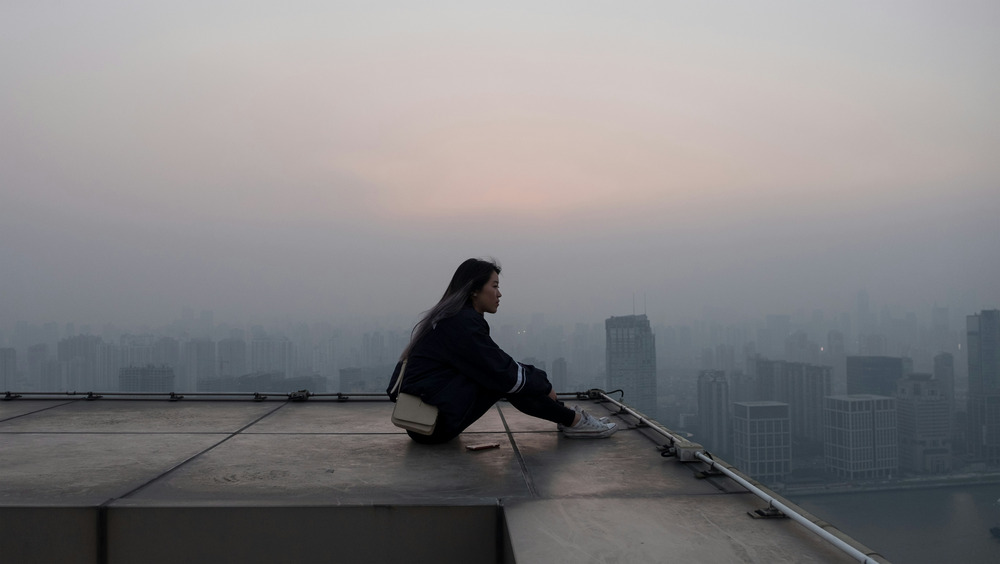

It’s sad how immediately relatable this is—how often I’ve known people, including myself, to have to do this to maintain some sense of privacy in public spaces, to avoid the event of men approaching us to start senseless conversation when we’re alone in public, just trying to be alone. At one level, I know this is frustrating, and I feel a knee-jerk irritation every time it happens to me. But at some other, more anxious level, I don’t want people to behave “just so” in public. I don’t want people to sense disapproval when they assert the kinds of conversations or interactions they want to have in public places.

I don’t want people to sense disapproval when they assert the kinds of interactions they want to have in public places.

Two days after the woman in the black dress left the restaurant on Fifth Avenue that summer of 1964, on a warm, rainy evening, Brennan sat at another restaurant on West 49th. She had just finished reading Time and was about to start on Newsweek when a man appeared at her side and said, “I want to know if you will have a drink with me.”

“No, thank you,” Brennan replied, “I’m waiting for someone.” She was sitting at a table for one.

“You are waiting for someone,” he mumbled, and went back to the bar. A few minutes later, two women speaking French came into the restaurant, and the man approached them, speaking in French, and began to ask if they would have a drink with him. At which point the head waiter came to him and said, “Please, Monsieur, you don’t know these people.” The man returned to his seat at the bar again gloomily.

“If everybody in the city were sorted out and set going in the right direction,” Brennan wrote later, “New York would soon be a very quiet place.”

The first thing I noticed when I read this was that she recounted both these incidents, first with a woman taking liberties and second with a man, in the same story and as examples of the same risk of New York becoming a “quiet place.” In her telling, both men and women can take liberties, and both can allow others to take privileges with them, or politely refuse.

The bigger thing of note was Brennan’s generosity towards other people. I find it moving, and I try to remember it when I find myself becoming frustrated by strange men at bars and restaurants who think that I am sitting alone because I’m “asking for” company or conversation. It’s offensive and disrespectful to assume that a woman sitting alone at a bar is only there because she couldn’t find company, and that she would be grateful for any at all. Reading Brennan’s New York vignettes, she doesn’t personally want to join this stranger for a drink; she also doesn’t want him to have to follow a certain code of public behavior or not be allowed to ask her. This difference feels crucial, especially because the stakes, for her, are about her city, about the risk of New York becoming a “quiet place”—a serious danger indeed, certainly more serious than the danger of being harassed by some man who insists on talking to me.

She doesn’t want to join this stranger for a drink; she also doesn’t want him to not be allowed to ask her.

Her love for people (including, sometimes, obnoxious strangers), is intertwined, then, with her love for the city. In our culture, we have expectations of people, maybe especially men, to allow other people their privacy in public places. It’s easy to fit those who interrupt this privacy into familiar archetypes. But we don’t usually see the sleazy interrupting men, the distracting or random or irritating conversations at a restaurant where we went to read Newsweek alone and in peace, as simply part of a larger fragmented New York rhythm—a rhythm that, mercifully, is not very quiet at all.

Brennan observed a lot of people who dined and drank alone. She watched the way they folded their newspapers, the way their raincoats billowed awkwardly, the way they moved their cutlery — and, more importantly, how they seemed to entertain themselves. I find it hard to describe how much I like to eat and drink alone, too: to sit with my bargain books at the windows of cafes and bars where bartenders often know my order already. New York’s bars and coffee shops delight me because there is so much “private” activity that happens in these fluid, homely public places. I often like to think of Brennan as my companion on these solitary nights out, when I people-watch through the window, or eavesdrop conversations on the other side of the bar, or doodle in my notebook or write letters to friends over my whiskey.

Brennan wrote that she was not a very curious person, that she did not go out of her way to explore or seek out new experiences, but I think her sharp observation was a kind of curiosity — a curiosity about people that made her not only a good observer but also a kind person, patient with people’s odd tendencies, generous in her descriptions of people that she really has immense power over, gracious about their vulnerabilities or awkwardness.

I’m new to this city. I think I will always be “new” to this city, which never really seems fully welcoming or legible. I don’t wish for these things in the cities I live in, for the chance to settle into complacency; nevertheless, it feels important to find the familiar, the human, the beautifully perfunctory, in order to feel a sense of belonging. I think this is what Brennan’s graciousness towards chance encounters, her quiet eagerness to observe, her willingness to be interrupted by strangers and by happenstance, was really about.

Brennan liked going into restaurants between 3:30 and 5 p.m., between the late lunches and the early dinners when the tables were all empty, and just sit.

“You can walk in and arrange yourself at the table of your choice, in the lavish solitude provided by the little sea of calm white tablecloths,” she wrote, “and look about you, even stare, be as curious or as indifferent or as watchful or as lazy as you are inclined to be — in other words, be yourself in a public place and still consider yourself polite. There is a great deal of virtue in feeling unseen.”

Brennan lived a transitory kind of lifestyle; she spent many, many nights in hotel rooms or in the apartments of friends who were away. When she walked into her friend’s apartment to stay for some days, the rooms, she said, seemed to know that she didn’t really “belong.” “The place has remained aloof since I walked in here with my suitcase,” she wrote. “‘We have no secrets,’ the two little rooms seem to say, ‘But we are his.’ And I think that when I leave the day after tomorrow, the same toy voice, whispering out of the walls, will cry, ‘What has been going on here? Who has been sitting in my chair? Who has been sitting in my bed?’”

This sense of alienation had to be combated, or negotiated with, somehow; in this way, the project of building a sense of home for herself, a comfortable condition around her in public where she could be herself, was her life’s work.

Brennan knew how to be alone. She transformed solitude into an art form.

Recently, on a trip back to my parents’ place in Bangalore, India, I was sitting in my favorite bar, a dingy hole-in-the-wall where liquor is sold in tetra packs and where everyone smokes indoors, at a table in a far corner and writing a letter with a pen I had borrowed from the waiter. A Maeve Brennan book was open in front of me. The waiter brought me a juice box of whiskey, and after some time the man sitting at the next table, drinking his third rum and coke, asked me, “Are you a journalist?”

“Something like that,” I replied, reluctantly looking up.

“I guessed,” he replied. He was middle aged and dressed pretty formally for someone who was drinking on a week-day morning. “Where are you from?”

I was getting really into what I was writing and it definitely wasn’t the first way I would have chosen to spend those few moments, but I responded, and after some vapid exchanges, we talked about our years living in Mumbai, about our favorite bar that had recently been renovated, where people would once huddle together with strangers on long rickety tables to make as much room as possible, watching cricket from the ancient television set while ash fell to the floor under dim yellow light. When you live alone in big cities like Mumbai or New York, fleeting relationships with strangers feel like a constancy; space is inevitably shared with other solitary people in some kind of transit through these public places. With no one permanently sharing my life, my days seem filled with the unplanned, the accidental, the serendipitous.

At one point, I looked down at my notebook, and the man said, “Carry on. I am sorry to disturb you.”

I was grateful to be let go, but as I looked down at Brennan’s book open on the table, I realized I was also grateful for the interruption. “It’s okay,” I said. “I suppose if I didn’t want to be disturbed, I would have been drinking and writing at home.”

I was grateful to be let go, but I realized I was also grateful for the interruption.

Jane Jacobs wrote in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, in her chapter about contact on city sidewalks: “Reformers have long observed city people loitering on busy corners, hanging around in candy stores and bars and drinking soda pop on stoops, and have passed a judgment, the gist of which is: ‘This is deplorable! If these people had decent homes and a more private outdoor place, they wouldn’t be on the street!’ This judgment represents a profound misunderstanding of cities. It makes no more sense than to drop in at a banquet in a hotel and conclude that if these people had wives who could cook, they would give their parties at home.”

She continued, “The point of both the banquet and the social life of city sidewalks is precisely that they are public. They bring together people who do not know each other in an intimate, private social fashion and in most cases do not care to know each other in that fashion.”

I like to think of all public spaces as some kind of extension of the physical sidewalk — spaces where the chaotic “ballet” of unplanned interaction that Jacobs described of the streets take place. People sit out in public because sometimes it makes solitude more interesting, even if many of the actual interactions we may have in public are irritating or boring or pointless. The point is that they’re unplanned.

I have in a folder of essay drafts a copy of one of my essays that my friend edited while sitting at a bar in the East Village. In one of the margins, amongst his comments, is an odd transcription of a totally uninteresting conversation about Chinese takeout that was going on next to him while he was reading my paper. I keep this because eavesdropping delights me; his attentiveness to, and interest in, a mundane conversation down the bar — not for what is being said, but simply for the sake of allowing other people and their voices to enter his concentration — delights me.

Brennan loved to eavesdrop, to make the presence of people on Sixth Avenue, in Washington Square Park, in Bloomingdale’s, at the florist’s, in the deli, at the Grosvenor Bar, a part of her own experience being in these places. She took a strange comfort in people and voices, whether she liked them or not. Watching people whose faces she couldn’t see, she said, was “both soothing and interesting. It is like counting sheep.” Similarly, listening into conversations in languages she cannot understand is also a pleasure.

“It is so nice to listen to voices without being delayed by what is being said,” she wrote.

People sit out in public because it makes solitude more interesting.

Through Brennan’s eyes, the experience of being bothered by a man at a bar where I’ve gone by myself to read and drink feels entirely different: it’s just a very real depiction of what she called “the accidental nature of our lives.” I realized that the unwanted conversations and the people who initiate them are not the point at all; I’ve started imagining they might even just be in a language I can’t understand. They’re all just accidental moments in a day or a week or a solitary New York life of unpredictability and quietly improper behavior, the kind that the head waiter at the restaurant on lower Fifth was so disapproving of. Improper behavior, of a quiet kind, seems a little necessary sometimes, if only just to make sure that we don’t all sink into a life of complacency one of the most interesting cities in the world.

I’d like to be allowed to behave like that woman in the black dress and pearl necklace sometimes, if I feel it, and I’d be very annoyed if someone told me to behave properly if I did what she did. But when I think about Brennan’s second anecdote and the waiter who pulled the man away from the Frenchwomen, I don’t think it would be less offensive if someone had to tell someone else to behave properly with me, either; codes of public conduct about behaving decently with women often have a patronizing tinge to them.

Brennan wasn’t entirely understanding of people being allowed to disturb each other in public. Once, she saw a woman walk into the Longchamps Restaurant and as she passed a group of noisy men, one of them called out to her, “Hey lady!” and burst out laughing. The woman was startled, and when she sat down she looked at her menu completely distracted and kept glancing over at the rude men until finally she quietly collected her things and walked out again, leaving Brennan at the restaurant seething. But a few minutes later Brennan found herself watching a fat woman with a satin scarf around her hair eating a creamy chicken dish with such intention and quiet focus that she was filled with admiration.

“Nothing could make her vulnerable or cause her shame or discomposure,” she wrote, “No one would ever drive her out of the restaurant she had made up her mind to dine in.” Even when there is a risk of being harassed while trying to eat out alone, both the woman who had to avoid a restaurant where men were taunting her, and the woman who was completely unfazed, are a part of Brennan’s world, and of the public life that she wants to capture. While she feels anger on behalf of the first woman, she also observes another way to be, some way to resist the shame that men would have women feel.

When I returned to Mumbai after a year away in New York, the man who runs the little tea and cigarette stall on the sidewalk outside my regular coffee shop saw me approach and opened a new pack of my brand of cigarettes without my having to ask, and said, “Been away?” in exactly the way I imagined Bill Kravit asked Brennan. There is a slow, almost haphazard way of creating a sense of belonging in cities like these. There’s something beautiful about the aimlessness of Brennan’s anecdotes, the way that so many of the characters clearly have very little to do. (“I had taken the afternoon off,” she writes in a Village restaurant, “But why, what excuse I had offered, I couldn’t remember.”) In the spirit of this languor, and this very slow enjoyment of a solitary life and all the accidental events it comes with, to be disturbed — whether by pleasantness or by rudeness — feels somewhat welcome.

Brennan helped me realize that there is a middle ground between “asking for it” and expecting to entirely be left undisturbed while sitting alone at a bar — that it’s okay, and not unfeminist, to be perfectly happy either being left alone, or having someone try and strike up conversation, whether I choose to engage them or not. There’s something special about feeling simultaneously exposed and completely in one’s own world. Sitting alone as a woman at a bar is not “asking for it,” but maybe it’s not an expectation to be entirely left alone either: it’s a tense, symbiotic relationship with my environment. My right to loiter, to take up space in public, is matched by others’ right to disturb me. One shouldn’t be allowed to negate the other.