interviews

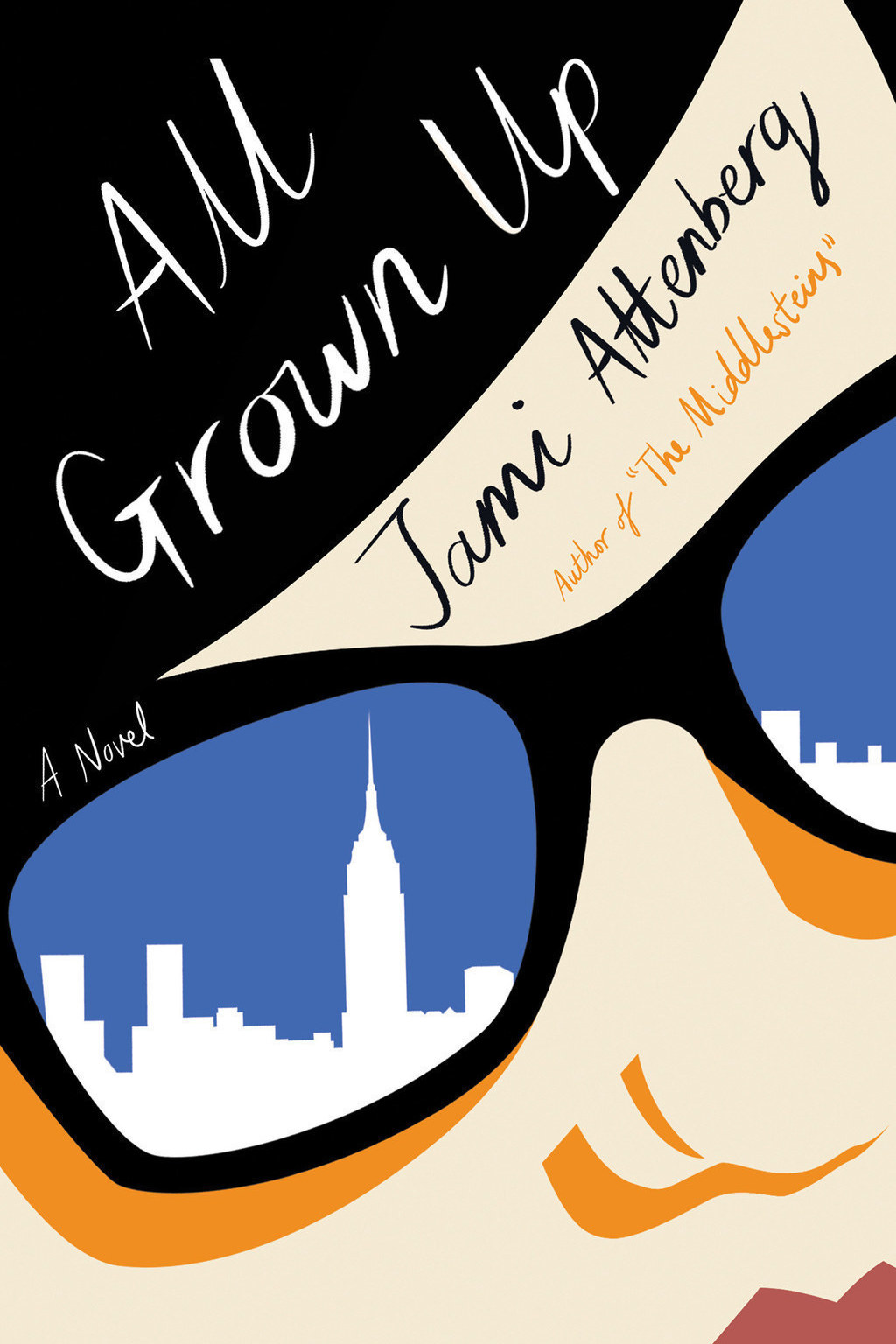

Jami Attenberg Has It All Mapped Out

The author of ‘All Grown Up’ on milestones, memoirs, and talking directly to the reader

After thirty-odd years of living in New York City, I don’t often miss my subway stop, even if I’m reading the most engrossing, page-turning mystery. But I did just a few weeks ago while reading Jami Attenberg’s latest novel, All Grown Up. I tell this to Attenberg as we sit down to chat at a Brooklyn bistro, and she seems both pleased and, a longtime New Yorker herself, suspect as to my navigational abilities.

All Grown Up is the story of a woman named Andrea Bern who drops out of art school in Chicago, moves to New York, and takes a dead-end job at an advertising agency. Through a series of linked but not linear chapters, we learn about Andrea’s junkie father and activist mother, her friends and her sexual encounters. However, a plot summary can’t capture what the book achieves. All Grown Up examines a process, the experience of becoming an “adult” in a world that oscillates between offering women equality and imposing outdated expectations. The novel’s sentences also propel you forward, each into the next until — and this is the Attenberg special — one stops you short with its dead-on accuracy. “Everyone should know their strength and that’s mine,” she tells me. “I’ll rework a sentence a hundred times to get that big moment.”

I spoke with Attenberg about creating a conversation with the reader, why her book is distinctly female, and how she mapped out the process of “growing up.”

Carrie Mullins: All Grown Up isn’t told chronologically. Did you write the beginning chapter first or did you start somewhere else and then find your way into the story?

Jami Attenberg: I had the story cycle of all the Indigo chapters first, and I wrote that long before I decided to write the book. It was about a friend watching a friend get married and have a baby and her marriage have trouble — I was just sort of watching these two characters interact with each other. Then I was sort of like, well that’s enough of that that. I came back to it about a year later when I was ready to tackle what else was going on. I wasn’t really interested in writing a “single person in the city” kind of book, and I figured out a different way to approach it. It’s not in linear order because that’s not what I was trying to accomplish. It has a memoiristic feel and I wanted to have the character be in conversation with the reader. She’s telling you everything you need to know about her life. If you made a top ten list of the most important things from your life, it wouldn’t necessarily be in the order they happened. The things that started popping up were just as I saw them mattering to her, and then there was some of me playing author and moving things around to create suspense or give information as it was needed.

CM: It’s funny you say that about the Indigo cycle because I felt like so many parts worked as their own standalone short stories. One of my favorite chapters — “Girl” — comes to mind. But I think when you layer the chapters on top of each other, you get something in a novel that you can’t really achieve from a short story.

JA: That’s right. They are all sort of their own short stories but at some point I had to bend them so that they were in service of a bigger story. By moving details over to this chapter or not giving all the information, I had to make that decision: is this a short story collection or is this a novel?

CM: I’m glad you went with the novel. I feel like everyone is writing short stories right now.

JA: Ha well, not me, sadly. I really think I’m a novelist more than I’m a short story writer. Some parts of the book could live on their own more than others. I have several story cycles within it, certain structures within it — like if a chapter is named after a girl it means one thing and if it’s got a different kind of title it means a different thing. I have a little map of it in my head, why everything is the way that it is.

CM: This is kind of strange, but I kept thinking it when I was reading. Have you thought about what the book would have been like if the protagonist was a male?

JA: It’s not strange but I’ll answer in two ways. One is that sometimes I go and talk to high schools — I don’t do it enough but I love it when I do — and for The Middlesteins one of the kids asked me what my book would have been like if Edie [one of the book’s protagonists] was a man. And I was like, that’s such a great question that I hadn’t considered, and it would have been a totally different book.

There is no way this book could have existed if Andrea was a man because a man doesn’t experience the same kind of pressures as a woman does in these particular ways. Nobody would give them the same kind of shit. She doesn’t get shit about not wanting babies, she’s just not a baby person, but she does get shit for not getting married or settling down.

“There is no way this book could have existed if Andrea was a man because a man doesn’t experience the same kind of pressures as a woman does in these particular ways. Nobody would give them the same kind of shit.”

CM: She also doesn’t get shit for giving up her dream of being an artist. She just abandons it and nobody seems to question that. Being single though, that bothers them.

JA: People don’t want the answers, they don’t want to hear the answer about why she’s not an artist anymore. She doesn’t really want to unpack it either. As for marriage — for almost every person in the book who’s in a love relationship, their partner isn’t helping them at all. That’s half the point of the book. She doesn’t know what to do to be a grownup, but they don’t know what to do to be a grownup either. They’ve done all the things that are supposed to make them “grown up” but that doesn’t mean that you are one. It just means you did these things.

CM: This book felt really refreshing.

JA: Yeah, I just didn’t see this character represented at all. I didn’t see anyone like her and I thought it would be helpful for people to see this character. She knows what she wants. She doesn’t know how to be happy, but she’s dispensed with a lot of the milestones.

CM: From a technical point of view, how do you write about the process of growing up?

JA: I literally made a list of everything that makes you who you are, and what was important to her. What happened with her dad? Why did she drop out of art school? What’s going on with her living space? I went through all of that and I created a little universe around her. I also read a lot of memoirs. I was reading The Argonauts and Patti Smith’s M Train and I read Chelsea Girls by Eileen Myles. They’re all written in different ways, but I saw what was important to all of them, and I watched the way that they talked to the reader because I wasn’t interested in treating this like it was a novel.

CM: That’s interesting because memoirs are freer from the confines of the plot devices we expect from novels. You don’t need the same hook.

JA: Yes. Because it’s all true. So I wanted it to feel all true, that was my strategy. There are moments where Andrea just talks to the reader. I’ve done that before here and there in my novels, where I sort of break that wall and talk to the reader. I feel like I’m in conversation with my audience, not necessarily in the first draft, but eventually I get to that point where I want them to know that I know they’re there.

CM: Everyone’s time is so limited now, especially for reading. When you’re having that conversation, is any part of you thinking about that, or the pressure to keep them engaged?

JA: Oh absolutely. I mean this is the shortest book I’ve ever written. I definitely thought when I was writing this about the way that people read now. I thought, you better give them all the information that they need up front. You better write it so that it feels super fucking important and urgent. So whenever someone tells me they read this in a day or I missed my subway stop, then I succeeded. I want them to be consumed and decide that it’s worth it. Our world is exploding right now. I don’t know if this will make you feel better, but maybe it will, just the act of reading and being consumed by something other than reality. It’s a genuine distraction, which means a lot.