essays

Jane and I: On Re-Reading Jane Eyre

by Selin Gökcesu

Reader, I did it. I reread Jane Eyre. It was, I’m sad to say, a bitter disappointment.

I reread Jane Eyre as part of an experiment aimed at resurrecting my love for reading. Soon after I enrolled in an MFA program in nonfiction, something completely unexpected happened to me: I could no longer derive any pleasure from books. At first, I blamed it on men. Although I started the program in the 21st century New York, the great majority of the books I was assigned were by male writers. How could I, a Turkish woman in her late thirties, be moved by the concerns and priorities of Updike, Roth, Nabokov, and Thoreau and lose myself in the literary discharge of their male minds? But, the reality was that I did not fare much better with women. The moment I turned my attention to contemporary female essayists, it dawned upon me that I shared little with them beyond an endorsement of the personal essay and memoir as literary forms. Most nonfiction works authored by women, I started to notice, were about illness and pain (mental or physical), men (as lovers or oppressors), and motherhood — topics I might be interested in socially, but not in a literary sense. I started missing the days when I was able to surrender my heart and soul to a character, be one with her (and, on occasion, him), and effortlessly, deliriously, read.

How could I, a Turkish woman in her late thirties, be moved by the concerns and priorities of Updike, Roth, Nabokov, and Thoreau and lose myself in the literary discharge of their male minds?

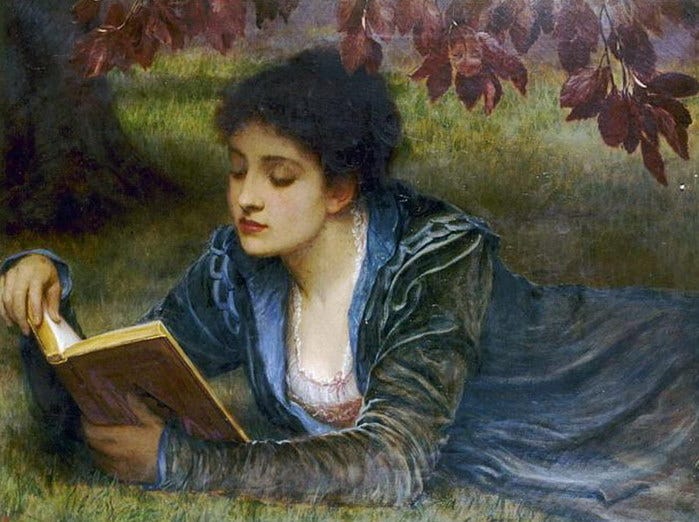

That’s when the idea occurred to me — how about Jane, my old friend? Perhaps she could respark my love of reading. Jane Eyre was the first non-picture book that I was given, when I was about eight. It was a small paperback, abridged for children and translated to Turkish. I referred to the protagonist as Janeh Eyreh, as silent vowels do not exist in my native Turkish. Our connection was immediate. I entered Jane’s life the way Alice entered the looking glass room. I stalked Jane through the dark and dreary corridors of Gateshead Hall. I fretted over her when she lost consciousness in the red room where she was so unjustly jailed by her awful aunt. I shivered in bed with her and Helen Burns the night Helen surrendered her soul to her maker. My identification with Jane was so complete that when Mr. Rochester fell in love with her, it was as if he fell in love with me.

Back in those days, reading was not an isolated activity that ended when my books did. I reread copiously and forced the stories into my life. I wanted to be Jane. I adopted her tastes. I decided to prefer rainy days because she did. Since our windowsills were awfully high and narrow, I could not read on them the like Jane. That didn’t deter me — I fashioned my own window seat by pulling a chair to the window and draping a curtain around it. I took up drawing to be more like Jane, and produced images of disembodied heads and stormy seas.

My identification with Jane was so complete that when Mr. Rochester fell in love with her, it was as if he fell in love with me.

Despite my earnest efforts, my life was nothing like Jane’s. I grew up in 1980s Turkey, not Victorian England. My mother, who survived childbirth twice and did not succumb to any epidemic, was loving. I had no mean aunt to lock me up. I went not to a boarding school but to a private one. I had never eaten porridge — hot, cold, or burnt. A diet of bread and water was out of the question even as an occasional indulgence — I was forced to eat an egg with my breakfast and three spoonfuls of yogurt with my lunch. All this only served to make me more interested in Jane’s peculiar life and spurred my desire to emulate her.

I was thirteen when I discovered that the real Jane Eyre was a lot longer than my little volume. I was overjoyed, and set out to read it. I breezed through Jane’s childhood and adolescence and was surprised to see how many pages I still had left — in my abridged version, Jane arrived at Thornfield Hall at about the halfway point. Soon after Jane became a governess, however, I found myself dreadfully bored and abandoned the book. I attributed my boredom not to Jane or Charlotte Brontë, but to to the fact that I was reading a dated translation into Turkish. Eventually, I did finish the unabridged Jane Eyre in the original English, when I was in my early twenties. It was part of a Victorian literature marathon that I deemed necessary at the time, to expand my knowledge of literature, and Jane blended in with Agnes Grey, Elinor Dashwood, Elizabeth Bennet, and Dorothea Brooke.

My childhood companion, the hapless, strong-willed orphan, grew up into a dour, self-righteous maid.

When I reread Jane Eyre at thirty-eight, I wasn’t expecting to relive my childhood. I was simply hoping that a novel that for me was so intimately tied to the joy of literature would allow me to lose myself in a book once more and perhaps trigger a reading spree of the sort I used to enjoy in my earlier days. The experiment started off well enough. Once again, I moved swiftly through Jane’s childhood and adolescence, this time admiring Bessie’s complex relationship with Jane and appreciating what an unusual character Helen Burns was. I also enjoyed Jane’s essayistic asides, when she stepped away from the moment to give the reader some background information or a piece of her mind. Nevertheless, soon after Helen died, my interest waned. My childhood companion, the hapless, strong-willed orphan, grew up into a dour, self-righteous maid. I found the passages of Jane’s religious moralizing insufferable and pedantic, even after making allowances for her 19th century roots. The relationship between Jane and her condescending, superior master Mr. Rochester (which I had once found romantic, if not sexy) was downright disturbing.

*

Though life experience may make one a better writer, it doesn’t necessarily render her a better reader. Youth reads with the benefit of an unbridled imagination that transcends isolated pictures and carries a story into life. The juvenile reader is not in search of originality, she is not even in search of a “good” story — any narrative that has forward momentum and a child protagonist will do.

The young reader, just like she can be friends any other girl her age, can identify with any heroine that fits her demographic. Presence or absence of toys, foods, and parents, being subject to unfair treatment by grownups, separation from family are all too relatable, independently of social background. When I was little, as a result of living in an economically mixed neighborhood, all my friends were children of poor, working class families that were more conservative and religious than mine. As I grew older, without any deliberate thought or action, my own friendships became limited to people who had similar educational and political backgrounds as myself. In parallel, I became more selective regarding the characters I could identify with and the writers I could tolerate, which slowly but consistently eroded my reading pleasure.

I became more selective regarding the characters I could identify with and the writers I could tolerate, which slowly but consistently eroded my reading pleasure.

With age, I grew sensitive to the writer’s political and moral agenda, separately from the protagonist’s. When I read Jane Eyre at eight, I gave little thought to Charlotte Brontë as a separate entity from Jane. At thirty-eight, what I perceived as Brontë’s moral standpoint rubbed me the wrong way. Nowadays, to enjoy a book, not only do I need to make peace with the characters but also, with the writer whose fingerprints I detect in every sentence. If I am put off by either, instead of sitting back and enjoying the story, I argue with it. Among my pet peeves are libertarianism, overt moralizing, unwarranted optimism regarding human nature, and a writer’s contention that he has within himself the entire human condition.

*

Technically, one need not identify with the protagonist or the writer to enjoy a good book. Although my eventual inability to relate to characters and writers did interfere with how much pleasure a book gave me, all through my twenties and early thirties, I continued to chain-read novels and memoirs written by a diverse group of men and women. I would find myself interested in a time period or a style — late 20th century American writers, pre-war British writers, social realism in the Turkish novel, Russian classics, literary horror — and read samples of it until I reached a point of saturation or boredom. This type of reading was not quite as gratifying as the way I read and reread Jane Eyre or Little Women as a child. Grownup reading was a little more detached from the characters, a little less enthusiastic, a little less visceral, but still one of my favorite pastimes.

I admired Wood’s ability to praise with intellectual rigor.

During my first year at the MFA, right about the time my anti-reading symptoms were starting to make themselves known, I picked up a small volume by James Wood titled How Fiction Works. I made slow progress but enjoyed it nevertheless. When a critic decides to praise the book he’s analyzing, it usually makes for an unexciting, predictable read. I admired Wood’s ability to praise with intellectual rigor. Moreover, unlike contemporary American writers, Wood was not overly concerned with being original, entertaining, or conspicuously passionate. He simply allowed his keen interest in the subject matter guide him and the reader.

I had read a number of the writers Wood analyzed — the Brontës, Jane Austen, Muriel Spark, Gustave Flaubert. However, as I made my way through How Fiction Works, I realized I had read them very superficially. Starting with the chapter entitled “Flaubert and the Modern Narrative,” Wood turned to the idea of “writer as a seer” and analyzed the types of literary details that masters bundle into sentences. Many of the excerpts he picked out to dissect were passages which must have once entered my mind (since they were from books I had read) but exited in silence, leaving no trace. For me, micro-level concepts such as literary detailing, the contraction and expansion of time, the proximity of the narrator to the protagonist’s mind, consciousness, or language were akin to faded stains on a waiting room carpet. I didn’t see them. They were overshadowed by the story and the characters. “I have to learn how to read,” I realized with panic. “I have to reread everything I ever read if I am going to keep walking around telling people that I read this book or that.”

“I have to learn how to read,” I realized with panic. “I have to reread everything I ever read if I am going to keep walking around telling people that I read this book or that.”

I didn’t realize at the time I read How Fiction Works, that my tendency to quick-read was actually allowing me to enjoy the story itself unencumbered by some yawning washerwoman over yonder, the purplish tint left behind by a sunset, the texture of the moss on the roots of some old tree, or the howling of the wind. What I thought was careless reading was in fact an unwavering loyalty to the plot. It made no difference to the old-me whether the writer collapsed a year into a paragraph or expanded a minute into a chapter — I remained equally oblivious to both as long as the narrative flowed smoothly. Detached narrators, omniscient narrators, the first person, the close third, I was blissfully blind to it all.

With or without James Wood, it was inevitable that the way I read would change after I started the MFA program. Once someone criticizes your work for perspective, suddenly it becomes impossible not to notice perspective in other works. Once a workshop classmate collapses a decade in one clumsy sentence, you become attuned to time in your own writing and elsewhere. Becoming hyper-aware of the nitty gritty of writing, however, did not not make me a better reader as I had originally expected. Paying attention to every word of every sentence is taxing. My new way of reading worked only to distance me from the story and its universe.

Paying attention to every word of every sentence is taxing. My new way of reading worked only to distance me from the story and its universe.

During my first semester at the MFA program, a translation professor told the class about Paul Valéry’s claim that he could never become a novelist because he refused to write arbitrary and purely informational sentences such as “The Marquise went out at five o’clock.” At first, I thought little of this anecdote. A year or so later, however, after I metamorphosed into a “close reader,” I began to find statements in the “The Marquise went out at five o’clock” category impossible to ignore and unbearable to read. Gone were the days that I could skim over such sentences and process them as information progressing the plot. They started making me cringe.

In How Fiction Works, Wood briefly addresses Valéry’s statement and dismisses it, concluding that the Marquise sentence is only arbitrary in isolation, not when it’s set up by a preceding sentence. My objection to the Marquise going out at five was not on grounds of arbitrariness alone, but also, banality. Unlike,Valéry, however, I do not refuse to write “The Marquise went out at five o’clock” — I will write anything that takes me from one paragraph to another. I just refuse to read it.

When my Jane Eyre experiment failed to rekindle my book love, I did not give up. I went on to read The Wide Sargasso Sea, which had a decade ago mesmerized me with its glorious imagery and its half-dream, half-nightmare universe. I had also been impressed that there existed a woman who had read Jane Eyre and identified not with Jane, but with Jane’s nemesis in the attic. But, I found no cure in The Wide Sargasso Sea either. No matter what I read, I saw the Marquise everywhere.

Nowadays, although I write everyday, my reading is limited to shop signs, emails, food labels, cosmetic ingredients, and book spines with an occasional glance at a back cover. But, I suspect that my evolution from repeat-reader to quick-reader to close-reader to no-reader is not over yet. The next stage may very well take me some place wonderful, laden with literary bliss where I meet Jane once more.