Interviews

Jeff VanderMeer and Nick Mamatas on the Death and Rebirth of the Short Story

Mamatas’ new book collects a decade’s worth of his unique short fiction

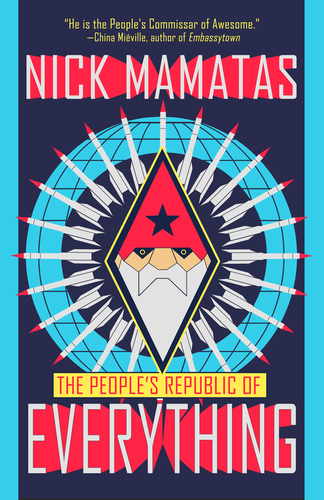

Nick Mamatas’ latest book is the just-released collection The People’s Republic of Everything. It includes the best of a decade of unique short fiction from an author lauded by China Miéville, Brian Evenson, and Matt Ruff. His best work reflects a kind of stubborn refusal to give in to the stupidities of the modern world, a critique of capitalism and an empathy for outsiders and those who don’t conform to the system.

Mamatas has worn many hats — novelist, short fiction editor, and book editor (currently for Haikasoru, bringing Japanese work to readers in English translations.) His seven novels include I Am Providence, The Last Weekend, Love is the Law, The Damned Highway, Sensation, Bullettime, Under My Roof, and Move Under Ground. He has been nominated for the Bram Stoker award five times, the Hugo Award twice, the World Fantasy Award twice, and the Shirley Jackson, International Horror Guild, and Locus Awards.

He has written numerous short fiction that has been published in publications such as Asimov’s Science Fiction and Tor.com, lit journals including New Haven Review and subTERRAIN, and anthologies such as Hint Fiction and Best American Mystery Stories 2013. He lives in San Francisco.

I interviewed him about the state of short fiction and his work via email in early August.

Jeff VanderMeer: Short fiction was dead. Then it wasn’t. Let’s assume it’s alive. Why is it alive, if so?

Nick Mamatas: It’s alive for a couple of reasons. One is that just over a decade or so ago, bookstores finally understood that they could sell anthologies of short fiction by treating them as though they were non-fiction. People really do wander into bookstores and say things such as “I love The Walking Dead. Got any books about zombies?” or “I’ve been hearing a lot about steampunk — got anything that’ll explain it to me?” and a big anthology with reprints by prominent authors and new or at least obscure material by less well-known authors is basically a textbook designed to answer those questions. Phonebook-sized anthologies by you and Ann VanderMeer, or by John Joseph Adams, really grew a generation of readers.

Then there’s the smartphone and commuter culture: a short story is a commute-length read and a smartphone allows for instant access even when people don’t sit down and plan to read short fiction in advance. But short fiction is only ever a few clicks away, and unlike large collections of fiction, which require the reader to enter a narrative world, then exit it only to enter another, reading in an interstitial moment and then reading another story eight hours later doesn’t tax one’s attention span so much.

Finally, the short story is alive because it was dead. Freed from commercial considerations — there’s no reason to sit down and try to write to the men’s magazine market or for the Saturday Evening Post’s specific requirements — writers can do what they will. Good writers win. Thus a book such as Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties can through sales for enthusiasm and sheer quality get a lot of buzz built around it, enter something like its seventh or eighth printing, and even get nominated for a National Book Award. If she had written those stories according to the commercial formulae of the 1950s or ‘60s, they wouldn’t have been as good and thus the book wouldn’t have done as well.

The short story is alive because it was dead.

JV: Do you feel the audience has changed since you started publishing fiction? And how has your fiction changed, in terms of what interests you to write about?

NM: I started publishing just as online fiction started becoming the norm; I’d say the audience has changed in that there is a drive toward the viral, which can lead to fiction that is a little too clever, or built in with a few too many winks toward contemporary Internet culture. On the plus side, as the Internet is a worldwide phenomenon, there is much more access to fiction from writers around the world, including work in translation or in other modes.

I’ve definitely become, over the years, much less interested in writing my version of this or that story type. Nobody cares what I think about spaceships or vampires or English professors or barflies, so I don’t need to weigh in on tropes. I just try to dig into myself and find what’s there.

Nobody cares what I think about spaceships or vampires or English professors or barflies, so I don’t need to weigh in on tropes.

JV: What do you love in the short stories you love? And what are some of your favorites?

NM: I don’t re-read novels as life is too short, but I will re-read short fiction, so stories that can withstand a second reading without losing too much of their power. A lot of short fiction is structured like a joke, with a windup and a punchline, so I dislike that sort of thing. If it’s all in the twist, it’s a waste of my time. I like stories that have humor in them, that veer off in an odd direction along the lines of the long middle scene in Godard’s film Breathless, and that use words cleverly.

“The Shadow, The Darkness” by Thomas Ligotti is perhaps my favorite short story. It’s hilarious. “Romantic Weekend” by Mary Gaitskill is a great one — one of the few pieces that can describe an outsider life as if described by an insider. “The Masonic Dream Engine” by Thom Metzger is excellent and I think wrongly categorized as an essay. “Reflections in a Tablespoon” by Gerald Kersh is the sort of nudge-nudge wink-wink story that people basically aren’t allowed to write anymore, and not only is it the best example of it, the framing narrative is actually more interesting and artful than the core of it. If I dare name a story I helped publish, I was honestly devastated when “Monologue of a Universal Transverse Mercator Projection” by Yumeaki Hirayama, which Masumi Washington and I included in our crime/sf anthology Hanzai Japan, didn’t receive any award notice.

JV: Is there a subject or idea you didn’t see expressed as much in short fiction that galvanizes you to write?

NM: I don’t see a ton of material about outsiders anymore. There are plenty of stories about middle-class types who nonetheless experience some neuroticism thanks to the precarity of their social position, but not many about true outsiders, who have different values and experiences than, well, the people who normally read short fiction.

Jeff VanderMeer on the Art and Science of Structuring a Novel

JV: How does humor or satire play a role in your stories?

NM: I’ve always been interested in humor and satire. I started reading science fiction thanks to that interest; I was shocked to find out how many science fiction writers actually believe in the goofy bullshit they propound in their stories. When I was a kid, I figured they were joking!

I also think humor has a place in virtually every story — people under stress will crack jokes, and irony and absurdity abound in dark situations. A story without at least a character attempting to say something funny strikes me as merciless and unrealistic.

JV: Do you have a typical way you begin writing a story? And how much do you need to know before you write?

NM: I suppose I’m concept-driven, which is fairly traditional. “What if…?” Then I hunt around for a voice and point of view. It’s in voice and POV that my stories differ from the average — whether that’s for the better or the worse is up to the individual reader. Once I have a POV, I find that many other story decisions are made for me, and I roar through to the end that I had imaged, realize it to be inadequate, and rewrite it. Then I am done.

JV: Can fiction change the world? Or at least the suburbs?

NM: Yes, but only when disguised as the true facts of the history of a people. Nation-building is a work of art, after all, so be suspicious of any national story, in the same way you should be suspicious of the flavor of a grape in a still life painting.

Be suspicious of any national story, in the same way you should be suspicious of the flavor of a grape in a still life painting.

JV: Anything you have no patience for any more in short fiction?

NM: Oh, plenty of things. Lazy use of scene breaks due to a failure to master transitional sentences. Excerpts from newspapers and journals that read nothing like newspaper articles or journal entries. Depictions of contemporary children with the names and juvenile preoccupations of the writer’s own long-gone childhood. Single-sentence paragraphs, especially when the last sentence-paragraph of the story. When only villains or otherwise pathetic characters masturbate, evacuate, or say the wrong thing at the wrong time. First-person narrators who apologize for being long-winded or meandering. There’s no need to apologize; I’ll just take the author’s own hint and stop reading.

JV: If you had to sum up the new collection in a sentence or two, how would you describe it?

NM: Stories about the difficulty of changing the world on purpose, and the ease of doing so by accident.