Craft

Joe Okonkwo on the Gay Black Entertainers of 1920s Harlem and Paris

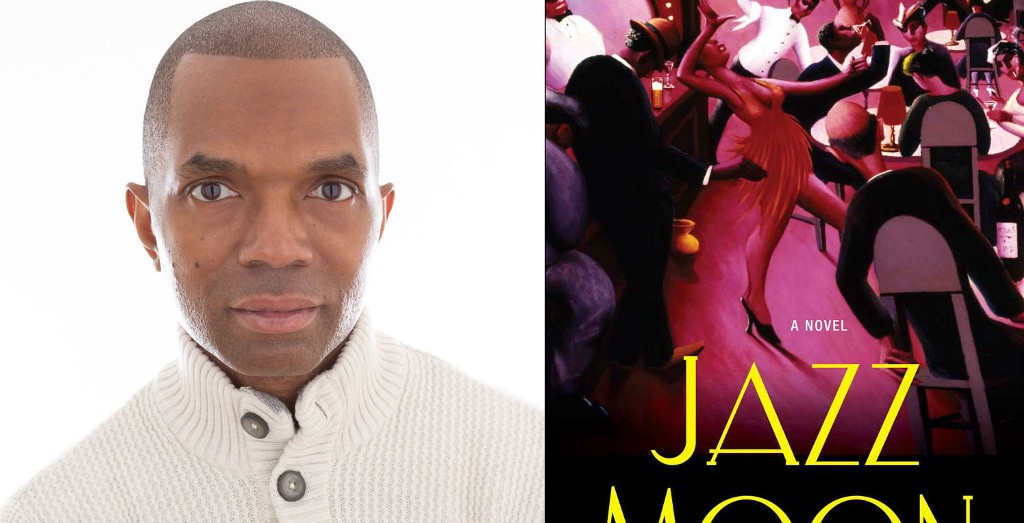

Joe Okonkwo, whose background is in theater and acting, recently published his debut novel, Jazz Moon, set in the roaring twenties of Harlem and Paris. In addition to his work as a fiction writer, Okonkwo is the prose editor for the Newtown Literary journal.

Jazz Moon follows its protagonist Ben, a black gay man and a poet in 1920s America, as he leaves his southern home for New York City, and then ventures even further, to jazz-filled Paris, in a journey to find his place in the world and come to terms with his own sexuality and creativity.

I sat down recently with Okonkwo over coffee, at a midtown branch of the aptly French-named Le Pain Quotidien. We talked about the evolution of Jazz Moon, stereotypes and identity, and the struggles of writing while working other jobs seven days a week.

Catherine LaSota: You lived in many different places before landing in New York City.

Joe Okonkwo: I was born in Syracuse, and then we moved to New Jersey. I was one. Then we moved to Flint, Michigan when I was two. We were there for six years, and then we moved to Nigeria, where my father’s from, when I was eight. My mother hated Nigeria — I did, too, actually — so she and I moved back to the United States, to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where she’s from, and we stayed there two years. Then we moved to Houston in 1981, and she’s been there ever since. I went to California for a couple of years, and then back to Houston, and finished my theater degree. I made my living doing theater for a while in Houston — children’s theater, stage managing, teaching. And then I moved here in June of 2000.

CL: And when you moved to NYC, were you still doing theater work?

JO: Yes, I came here to do theater, to be an actor. I did maybe three off-off-off-off-off-off-off Broadway plays. But then I gave it up, because I can’t afford the headshots, the classes — I couldn’t do it. Also, if you’re an actor in this city, you have to be willing to be itinerant, you have to be willing to do a sublet here for three months, and a share there for two months, and I cannot do that. I admire people who can, but I can’t do it.

CL: You crave more steadiness.

JO: Yeah. So I gave up acting and went into web production.

CL: When was that?

JO: It must have been 2002. I was working at the Metropolitan Opera in the customer service department. I was the manager of a section called Issue Management. We were the problem solvers. So you can imagine dealing with opera customers, what that must’ve been like. It was challenging, it was a growth experience because I’m actually a very shy person, but I couldn’t be shy there. I had to get on the phone, talk to customers, explain things, apologize. But I got to go to the opera all the time, and I’m an opera queen, so…

CL: Were you writing this whole time, during your acting and work with places like the Metropolitan Opera?

JO: Yes. Not really getting published, mostly plays and poetry and some short stories. I started writing in probably first or second grade. Stories. And then I wrote my first novel when was 11 or 12.

CL: Do you still have that?

JO: Oh, I wish I did. I wrote it in pencil in a spiral notebook, which has long, long since gone. The story was called, “Conrad, City of the Demons.” It was about a drifter named Jerome Perkins who goes into this Old West town, and everyone is possessed by demons.

CL: Sounds very dark! Let’s talk about Jazz Moon. There are so many things being explored in your novel. It takes place in the 1920s, both in Harlem and in Paris. It touches on art, on homosexuality — on a lot of different pretty big themes, I think, such as identity, love, loneliness, and creativity. What sparked this project for you initially?

JO: What started it was just my love of that era. I mean if there was such a thing as a time machine, and I could go back to any era, I would go to the Harlem Renaissance.

CL: Why?

JO: It was an incredibly difficult time for blacks because of the overt racism — lynching and Jim Crow, and separate restrooms and separate water fountains — but it was also a really rich time in poetry, literature, art, and political movement.

It was really the first time that people realized that black was not only beautiful but also marketable.

What was happening politically then basically built the foundation for the modern civil rights movement of the ‘50s and ‘60s. And the music, the jazz. It was really the first time that people realized that black was not only beautiful but also marketable.

CL: Interesting. That’s America, that’s capitalism, searching for what is marketable.

JO: A lot of jazz blues records were made. A woman named Mamie Smith, in 1920, made a record called Crazy Blues, and initially the producers didn’t think it was going to sell. It was a black woman singing blues — that wasn’t gonna sell, right? It sold, and it started this blues recording frenzy. Those records were called “race records,” because they were made by people of a different race. And the section of a company that was in charge of race records was called the “race records division.” And the people who sang these records were called “race stars.” These record companies were amazed, flabbergasted, that there was a market. So people like Bessie Smith, Alberta Hunter, Ma Rainey became big stars.

CL: What do you think about the fact that people are given legitimacy in a certain part of society only if they are marketable?

JO: Well, I mean, that’s kind of the struggle of artists, isn’t it? You want to be true to yourself and make your art, but also make a living. And if you’re really ambitious, find fame and fortune. But you have to find that market, appeal to a certain sizable population, and if you can’t you’re not going to find that kind of commercial success.

CL: Something you explore in Jazz Moon is a kind of exoticism of black people, especially from Harlem, in Paris. Different characters struggle more or less with being categorized in a certain way. Is this a fair assessment?

JO: Sure. You have people like Josephine Baker, who played upon the stereotypes people had of blacks and Africans. And you have a character like Ben, the main character, who kind of tries to resist that. He doesn’t like being the exotic celebrity. Well, I think he likes it a little bit. But he doesn’t want to be an exhibit. And that’s what a lot of the blacks in Paris are. They are the entertainment. They’re not just entertainers, they are the entertainment.

CL: Ben is a very interesting character. He’s struggling to figure out his own motives and who he is. So when people are giving him a certain identity from the outside, I can see him liking that, but also struggling against it as he tries to make an identity for himself.

JO: Right. He says that he’s sick of jazz, and he’s sick of people asking if he knows Josephine Baker. It’s like a running joke. And he gets tired of that. He resists that, but then at the same time, when newer blacks from New York come to Paris and become the celebrities, he’s a little bit miffed that he’s not getting the attention anymore. So he likes the attention, but he doesn’t at the same time.

CL: At a certain point Ben is musing on love, and how the “plot” of love has supporting characters. Were there certain characters that were very vivid to you as you started this novel? Did you have any central or supporting characters in mind?

JO: When I started, I don’t think I had any particular themes I wanted to explore. I started with place and time period and went from there, and the people began to populate the story — it kind of happened. I didn’t set out to write a story with particular kinds of characters, to represent anything in particular. Some of the characters are based loosely on, if not actual people, figures from that era, especially in Paris. Blacks who went to the club scene, the art scene — some are a conglomeration of real life people.

CL: Can you talk a little about the role that research played in the creation of Jazz Moon?

JO: I came into the project having a great love for the era, knowing something about it, having a great love and admiration for the music. There were a lot of black shows and a lot of black vaudevillians, and that fascinates me. I did a lot of research on the time period, a lot of research on the literature of the era, the music of the era. And Paris, and gay bars. I did a lot of research on blacks in Paris, black entertainers in Paris. A lot of reading, a lot of exploring online. When I came into the project, I knew something, but not as much as I do now. It’s interesting, when finishing the novel, and getting involved in marketing, I’ve learned even more about the Harlem Renaissance and the music, and I found out a lot about the period. I’m not done with the Harlem Renaissance.

CL: Do you think you’ll write about that time period some more?

JO: Yes. I don’t know if it will be my next novel, but I’d like to write a story about someone who had a cameo in Jazz Moon. Her name is Gladys Bentley, and she performed at a place called the Clam House. That was a real place. She was a drag king, a blues singer and a pianist. She was a very big woman, very large, and she was known for wearing a white top hat and white tuxedo and tails. She would take popular songs of the day, and she’d change the lyrics and make them naughty, and she would openly flirt with women in the audience. She claimed to have gotten married to a woman in an Atlantic City wedding ceremony, but no one knows the identity of this woman or if it really happened. And then in the 50s, she was interviewed in Ebony magazine, and she renounced her lesbianism, and she said, I’m taking female hormones now, and that’s cured me.

CL: Her life sounds fascinating.

JO: Yeah, not a lot is known about her, which is kinda good for me, because it gives me a lot of license. So I think that will be my next big project.

CL: There are parts of Jazz Moon that are very sexy. I’m sure that, as an editor at the Newtown Literary journal, you see many attempts by writers trying to write sexy, with greater or lesser success in doing so. Do have any advice for how to write sex successfully?

JO: In early drafts, I went probably too far with the sex. In workshops at City College, people and my professor would say, if you want to reach a wider audience, you’re going to have to tone down the sex. You could argue that that’s pandering, but I would say that it is not pandering — even if you take a mainstream audience out of the equation. One thing I don’t like about about gay fiction, is that so much of it is so sex-centered. So much of it is all about sex, it’s all about the shirtless guy…there’s nothing wrong with that, but, you know, there has to be more to it than that. So the toning down of the sex was also about — I don’t want to offend anybody — but I didn’t want it to be the typical gay male book, all about sex. You know, obviously there’s some of that, there are some hot guys in there. But I didn’t want it to be just about that.

CL: It reads to me as a story about love primarily, which sex is involved in, but it’s a love story.

JO: It’s a love story, it’s a coming out story. In his lovely endorsement, David Ebershoff said it’s a story about “traveling far to find oneself.”

CL: It’s a love story in terms of romantic love, but also in terms of loving oneself.

JO: Absolutely. That’s one of Ben’s big struggles — to love himself, how he looks, how he is, realizing that he is worthy of being loved not only by other people, but worthy of being loved my himself.

CL: Did Ben emerge as a major character fairly early on?

JO: Oh, from the very beginning, absolutely.

CL: How many revisions did this novel go through, would you say?

JO: I didn’t even count, I just kept revising and revising and revising, and when it was accepted by the publisher, obviously I revised even more.

CL: Was it a very different novel in the first draft than as it exists now?

JO: I would say it’s not so much a different novel — I didn’t change any of the structure — but I went deeper, and I fleshed things out, made things clearer, found some more emotional depth. I’m a big fan of language. So that was a big focus, making the language as potent as possible.

CL: Speaking of your focus on language, there’s a lot of original poetry, and also song lyrics, in Jazz Moon.

JO: I identified primarily as a poet for a long time. I self-published a book of poetry back in 2002, and when I flip through the book now — there might be some flashes of good writing, but for the most part, it’s not something I’m proud of. Poetry is hard. It’s harder than fiction. Erica Jong gave an interview once, and she said writing poetry required being in a higher state of consciousness. And I agree with that. If I never write another poem again, I won’t regret it.

CL: Yet you wrote a book that contains a lot of poetry! What was that choice about?

JO: Well, you know, Ben is not necessarily based on me, but there’s a lot of me in him, and at the time I started writing this story, I was still probably identifying more as a poet than as a fiction writer, so I think that’s probably where that came from.

CL: So, now, as you’ve mentioned to me previously, you’re working day jobs seven days a week. When do you write?

JO: Right now I’m not. Too much going on, working seven days a week, and promoting the novel, and so right now I’m not.

CL: What did it look like when you were writing Jazz Moon? How were those writing sessions? Did you have any regular routine at that time?

JO: Yeah, I was writing pretty much every day. Sometimes early in the morning, sometimes after work, on the weekends, back when I used to have weekends.

CL: What were you reading as you wrote this novel?

JO: Everything. Toni Morrison, Alice Hoffman, Diane McKinney-Whetstone, Ernest Gaines, James Baldwin, Richard Wright, Andrew Sean Greer, Gloria Naylor, Mary Shelley, Thomas Hardy, Jane Austen.

CL: A good list. Have you read anything recently that you especially loved?

JO: Langston Hughes’s first collection of poetry, called The Weary Blues, published in 1926. And another Harlem Renaissance novel calling Passing, by a woman named Nella Larsen. The book is about blacks who are light enough to pass as white, and all that entails. Great book.

CL: Jazz Moon is your debut. How does it feel to publish your debut novel?

JO: I found out a year and a half ago it was going to be published by Kensington Books, so this whole year and a half has been anticipation and excitement and preparation, and now in less than two weeks it’s going to be here, so I’m incredibly happy and excited, but also scared because, to be perfectly honest, I’d like to make a splash. I’d like to move the dial, in terms of my writing career, and get out of this 9–5 web production thing, which I’m grateful to have, because it pays the bills, but it’s not what I really want to be doing with my time. I want to write.

CL: Your ideal would be to write full time?

JO: Write, edit, and teach full time.

CL: Was there anything that happened in that year and a half of time since your book was accepted by Kensington that was especially surprising to you?

JO: Well, yeah. I was laid off from my job of almost 6 years, 2 ½ years ago, and I’ve spent a lot of time unemployed and underemployed. And at the same time I couldn’t find a full time job, all these great things were happening on the writing side. I found an agent, I found a publisher, I became an editor at Newtown. Starting in 2017 I’m going to be an editor of Best Gay Stories from Lethe Press. I’ve gotten some short stories published, I’ve been nominated for a Pushcart Prize, I’ve been able to rack up great endorsements from people like David Ebershoff. All these wonderful things have happened writing-wise, so that part of my life is starting to fly, but the other part of my life, the one that pays the bills, has been, up until recently, some of it has been burning down. It’s been this weird dichotomy, on the one hand, to find this success as a writer, but at the same time, I’ve thought, how am I going to pay the rent in a couple of months. So it’s been a very odd time.