interviews

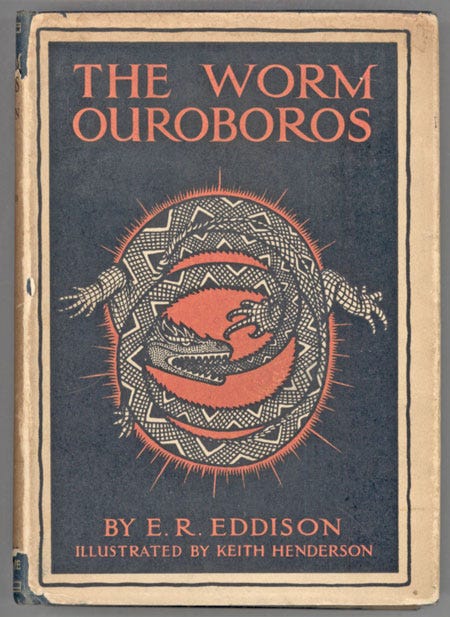

John Darnielle on E.R. Eddison’s The Worm Ouroboros

Colin Winnette admires the writer and musician John Darnielle, so he asked him to suggest a book that they might talk about. John Darnielle picked The Worm Ouroboros by E. R. Eddison. Then they talked about it.

John Darnielle is a writer, composer, guitarist, and vocalist for the band the Mountain Goats; he is widely considered one of the best lyricists of his generation. He lives in Durham, North Carolina, with his wife and son. He is the author of Master of Reality (a 33⅓ book on Black Sabbath) and Wolf in White Van, which was nominated for the National Book Award.

CW: Can you provide a brief description of The Worm Ouroboros? Something to ground anyone who hasn’t read it.

JD: It’s a classic quest narrative — there’s an evil to destroy, and four noble warriors take to the high seas and rough terrain to meet and defeat it. It all takes place on a distant planet where monsters range and magic holds sway.

CW: What’s your history with this book? From what I can tell, this one’s out of print. I placed a few orders online, but when those didn’t arrive for several days, I bought an ugly, old, red edition, I came upon in a used bookstore in San Francisco. Now I have like three copies. [If anyone wants a copy, be the first one to Tweet at me and it’s yours]. What got you to pick this book up and read it?

JD: I don’t remember where I bought my own used edition, a beat-up paperback with a green border. I think I grabbed it after remembering, from years ago, that it had been cited as a Tolkien precedent. I haven’t read Tolkien since grade school, but back then he was a huge favorite of mine, so when I remembered Eddison (thirty-odd years later) I thought I’d give him a shot. It sat on my shelf for a number of years, which is the fate of most books I buy, and then one day I said “what about that one?” and it really just grabbed me from the first chapter.

CW: What motivated this recommendation? Is this a book you think more people should read, in general? Or just one you’re still trying to wrap your head around?

JD: I try not say what I think people should read, people should read whatever they want, but I do feel like it’s a book some people might really enjoy if they got their hands on it. Like, a certain kind of person who’s taken pleasure in fantasy novels and/or Arthurian legend — this hits that axis in this weird, solitary way. It’s so much its own thing, but it kind of sets a precedent for a lot of later stuff. It feels kind of like it was drawn up without a blueprint — and often it seems to lack forward-motion, which is something that really interests me, when a book, either by design or lack of it, is able to hit these abiding lulls — these sort of open spaces.

CW: That’s interesting. When I first read it, I was struck by how compelling the action of the story is (the wrestling match for sovereignty of Demonland and how quickly things get rolling from there). You’re just kind of plopped into this very high stakes situation (sort of like the lords of Demonland). But then there is this weird back and forth between very compelling scenes/energies — power struggles, subterfuge, challenged or shifting loyalties — and these large swaths of time that pass between events and so much doubling back. Which parts stood out to you as particularly stationary? And what did you make of them? How do you experience those open spaces?

JD: Well, the long sojourn before the second expedition to Impland — it’s not boring, but it’s sort of time-biding stuff. You get that feeling, which I love in old fantasy or science fiction, that the author is luxuriating in the world he’s envisioned — that he wants to write scenes that kind of drag on where an editor might say, “Let’s get back onto the high seas here.” For me, I think Eddison’s ambition outpaces his style a bit; to really nail the mood he wants in “A King in Krothering,” say, you have to sort of rise to a different style, but Eddison’s style is dialed in from the first page. But then sometimes, when I feel like I’m seeing with Eddison’s eye, I want to remain with his characters at the idle dinner conversations. This may just be the long way around saying “he’s best in the action scenes, but I have affection for how hard he’s trying in the downtime.”

CW: Your new novel is full of references to sci-fi/fantasy. Some of my favorite parts of the book are the narrator’s descriptions of old fantasy movies or the mail-order swords he sees listed in magazines. What role did fantasy play in your young reading life, and has it changed in your adult life? (I’m asking specifically about genre here, but feel free to go whatever way you like with this question).

JD: I aligned with fantasy as a young science fiction / fantasy reader — I liked the fluffy stuff. Unicorns, dragons. Space was cool but mythical creatures, magic, wizards, talking trees — that was what inspired me when I was ten, eleven, twelve years old. I put that stuff aside when I began to have Pretensions — when I became a Serious-Minded Young Man — which I don’t regret, it’s great to go through phases. But I’m glad as a grown-up to have come back around to magic stuff, magic is really such a wonderful idea.

CW: What stuff did you pick up when you became a SMYM with P?

JD: Harlan Ellison was kind of ground zero for the SMYM with P, he was the gateway. He made me want to be Taken Seriously. But then I found Faulkner and it was Faulkner all day, and awe rather than any aspirational “one day I’ll break bread with these giants” feeling. Sheer awe. And also Joyce — Dubliners mainly, I didn’t kid myself about trying to be able to scale the big ones (though that didn’t stop me from getting my hands on Finnegans Wake). And I read poetry, 20th century poetry. Paul Celan. Sylvia Plath. Czeslaw Milosz’s anthology Postwar Polish Poetry.

CW: Let’s talk about magic. What’s wonderful about the idea to you? What can magic do for a story, and what are the pitfalls? And did you consciously choose to leave overtly magical things out of Wolf in White Van? Did you ever sit down to determine the “rules” of that reality, or did you just put one word in front of the other and look back to see a world that looks a lot more like our own than, say, Eddison’s Mercury?

JD: Magic I think for me is kind of personal. Like, as soon as magic is in play, then I am given permission to imagine a different world, one in which magic things might happen — one where maybe I get some magic to wield if I’m lucky. Where cool stuff might happen at any given moment, cool stuff you wouldn’t even guess at. And for as long as the story holds, I’m kind of living in that world. I don’t really do any rules-sketching ahead of time, although in Wolf I did want to be true to the physical reality of 80s southern California in memory; it was important for the locale to be vivid. I think it’s fine to trade stark real visions for colorful vivid ones but what I wanted in the world of the book was a sort of uncomfortable clarity to contrast with the limitless expanse of the imagination.

CW: What did you make of the opening of this book? The “frame story?” How does it (or does it even) serve the book? And what…happens to it?

JD: It goes away! That’s part of what I love about the book — it’s not a great big mess, but it feels almost like somebody’s hobby. It’s really personal-feeling, in a way. He sets up the story in a pretty traditional English way of framing a fantasy story, but his heart’s not even in that, his heart is with the Demons. However! there are two other volumes in the story I haven’t gotten to yet — maybe he closes the frame in The Menzentian Gate? I have it on my shelf, I’ll get to it at some point — I have a mini-collection of fantastic stuff, more Arthurian stuff than straight fantasy, but I have both the other volumes in the Eddison trilogy. It took a while to hunt them down, they’re nowhere near as well-known, but I’m curious about them.

CW: I grew up on Tolkien (literally, The Hobbit was a bedtime story), but haven’t read much high fantasy besides. This book struck me as interesting because it’s a complicated and well-imagined/described world, but it also leans heavily on familiar names/locations. Little effort is made, though, to engage with those references, outside of the immediate effects of their familiarity. The story takes place on “Mercury,” though it…shares nothing with the planet Mercury, as we know it. It just an “other” place, far away and inaccessible to us. Also, rather than having completely made up names, the races in the book are the Demons of Demonland, the Witches of Witchland, the Imps of Impland, the Goblins of Goblinland, etc. But when described these characters sound very human (though I think the Demons have small horns?). The physical world of the book, though, is well-imagined and beautifully rendered at times. How does this combination of the familiar and the uniquely imagined affect our reading of the book? Or your reading of the book?

I want to start a band called Witchland when I see that, you know?

JD: Did we mention that Tolkien esteemed this book somewhat, or was said to, with some reservations? One thing I like about it is just the inversion you mention — Eddison’s physical descriptions really reverberate, but his naming has none of Tolkien’s learned choices — he just settles on “Witchland,” which is so so great. Witchland. I want to start a band called Witchland when I see that, you know? But you can see so much of Lord of the Rings in this — there’s no way Gollum isn’t modeled on Mivarsh Faz, they’re the same character except that Gollum gets his big spiritual presence and metaphorical heft. Mivarsh is the Gollum you’d actually meet: “something’s up with that guy,” you’d say. But you’d never know what it was. I do like how Eddison can’t seem to fully break free from the world-world; his people are essentially knights-errant, but wants them in possession of some otherworldly quality…so the place is called Mercury.

I do think when he describes magic, which he does sparingly, he really hits his heights, though.

CW: The conjuring in the Witchland section is a lot of fun.

JD: You mean “The Conjuring in the Iron Tower”? This is probably my favorite part of the book — it’s so lush and weird. And hermetic, you know — like, this scene with a guy and a book and a tower — it’s got an iconic feel, like a tarot card.

CW: The prose is worth calling out. What do you make of it? The man who sold the book to me described it as “purple prose,” I think pejoratively. I thought it was great, though, particularly the descriptions of the physical world. And the dialogue is lively, compelling, even funny, at times. Overall, I found the prose commanding. It was a singular experience, stepping into this world.

JD: Oh it’s really purple. In an awesome and completely singular way. Eddison’s affecting this medieval tone that he doesn’t really seem to have mastered, but he’s pretty consistent within his own version of it, so it becomes very much its own voice. It’s like one of those records you find at the Goodwill with a weird sleeve and when you listen, you feel like it’s off in its own cluster of references — that it stands alone. There’s some stuff in higher fantasy that I miss — that wistful Arthurian tone that makes Malory so great — but in its place is something unique. There’s nothing quite like it.

CW: You’ve twice spoken to a kind of lack of “mastery” or polish, though from different angles — with regard to the prose, and earlier when you mentioned those “open spaces,” the book’s sudden lack of forward momentum. The book has this weird tension between the very constructed feeling of fantasy or “historical” fiction and these weird quirks that make it unique but also grant it a weird, almost childish, enthusiasm…like he’s trying things out and having a little fun.

JD: Yeah, I think that’s a big part of its appeal — like, you get the sense this guy either doesn’t expect to sell many of these books, so he might as well just be true to his inclinations….or maybe he’s got a lot of books in him so he follows his bliss on one instead of really playing for the historical record. He understands structure, but he dallies here and there, he gets a little distracted and doesn’t apologize for it. It’s kind of…ambitious on its own terms, rather than the “here, let me wow you” terms that’re kind of par for the course everywhere.

CW: *spoiler question* I found the ending of this book fascinating. I couldn’t help thinking about high fantasy as a concept, as a kind of location. You yourself described being “transported” by the book. At the end of the book, the Demons are depressed that their adventures have come to an end. They’re left with peace and peace is boring. They dream of going back to the start, to the beginning of the book, and reliving the epic fantasy we’ve just read. Narrative implications aside, it’s very similar to the feeling readers get when finishing a book we really love — we want to be back in it, we don’t want it to be over. The only choice we have is to go back through and read it again. What did you make of the end?

You want rest, but at rest, you pine for action.

JD: I think Eddison is taking this from Camelot — from those last meetings of the round table before the quest for the grail, when Arthur senses that their fellowship must change. These, in Malory (which I almost chose for you to read, but Malory is a real commitment), are some of the most moving passages in all literature. I dig the end — that itching feeling, that lust for battle even though the point of battle is to get through it. Right? That’s just human experience. You want rest, but at rest, you pine for action. But the ending’s a circle, right? They don’t dream of going back — they do, it’s revealed that the Ouroboros is in fact their story. The Ambassador from Witchland arrives anew. They’re going to do it all again. Or are they? There’s those other two books. I think I’ll put one of them next in my queue for after I finish Aubrey’s Brief Lives, which I’m working on right now.

CW: I’ll put Malory in my queue. Like the Demons, I’m itching for more of this stuff.

It’s a brilliant kind of doubling back (which the Demons do a lot of in this book), where at the closing of the book it seems that we’re back at the beginning of the book, back at the catalyzing moment — but are they in an endless loop (a satisfying enough ending for a book like this, if read on its own), or will they, or someone else, change their course — and if so, what will happen (a great setup for a trilogy)?

JD: I think that loop-ending is so satisfying, and the suggestion — especially given that the ouroborous then appears in the book — is that these guys actually exist only in and for this story, that this is who they are. And I love that, it’s the sort of ancient postmodernism that always lets the past remind us how playful fiction has always been, how open the space has been since forever.

CW: Will you leave us with a quote?

JD: “Therewith the earthquake was stilled, and there remained but a quivering of the walls and floor and the wind of those unseen winds and the hot smell of soot and brimstone burning. And speech came out of the teeming air of that chamber, strangely sweet, saying, ‘Accursed wretch that troublest our quiet, what is thy will?’ The terror of that speech made the throat of Gro dry, and the hairs on his scalp stood up.”