Reading Lists

Kicking Off Our ‘Read More Women’ Series with Maria Dahvana Headley

The author of ‘The Mere Wife’ recommends five books that aren’t by men—and you can win them all

The New York Times series “By the Book” asks prominent authors about their literary influences and favorites—your go-to classic, your childhood reading, your favorite book to recommend. The answers, like the authors, are delightfully varied, in many ways. In others, they’re troublingly consistent.

“When male writers list books they love or have been influenced by… why does it almost always seem as though they have only read one or two women in their lives?” asked Florida author Lauren Groff in her May “By the Book” interview. We’d noticed the same thing; six months earlier, a dude-heavy list by The Martian author Andy Weir had inspired the tweet that started our “Read More Women” rallying cry. And in light of that simple mission statement—read more women—we’re launching a new series, which we’re thinking of as a stripped-down, feminist version of “By the Book.” Twice a month, we’ll have some of our favorite writers—of any gender—discuss their favorite or most influential books that aren’t by men.

“We can’t escape being born into a society that has contempt for women tattooed on its bones, but we can change ourselves,” says Groff about our new series. “It is vastly important to read more female authors: to see women as worthy of our imagination and respect, to understand a woman’s full humanity, to reclaim authors who have been unjustly forgotten by time because of their gender, to meet the minds of geniuses new to us, to expand the Canon, and to work toward the equality of all humans that is promised by the better angels of our society, but which in our actions and silent and insidious biases we so often fail.”

We invite you to follow your better angels by investigating our featured authors’ favorite works by women and nonbinary writers. This week, we’re even making it easy for you. Follow our partner MCD Books on Twitter, tweet a link to this article with the hashtag #ReadMoreWomen, and you could win one of our Read More Women tote bags filled with all the books Maria Dahvana Headley recommends, plus her new book The Mere Wife!

Which brings us to our first featured author. (Don’t worry, the introduction will be shorter next time.) Maria Dahvana Headley is a bestselling author of adult and young adult novels (and one internationally bestselling memoir, The Year of Yes). The Mere Wife is a modern retelling of Beowulf set in a posh subdivision; Kelly Link called it “a consciousness-altering mind trip of a book” and no less than Samuel R. Delaney called it “a book to call up an old story in the newest possible way.” Headley’s most recent books before The Mere Wife were the young adult fantasy novel Magonia and its sequel Aerie, both of which got rave blurbs from Neil Gaiman, with whom she’s also collaborated to edit the short story collection Unnatural Creatures. Her five recommended novels by women are for anyone who courts the dark and strange.

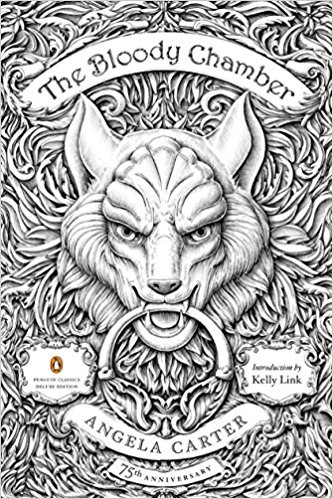

The Bloody Chamber– Angela Carter

There’s no forgetting the moment you notice that the shelves you’ve been assigned are full of men, and that you haven’t seen women’s names on them since you were a little girl. I emerged from a childhood of reading stories about girl witches, explorers and adventurers written by women born in the first bits of the 20th century — Madeline l’Engle, Elizabeth Enright, Margaret Storey and Zilpha Keatley Snyder — into…Bukowski, Kerouac, a bunch of boy beats whose female characters weren’t the ones driving the universe. Then, when I was twenty or so, in college studying playwriting and reading more of the work of men, I was questing in a Barnes & Noble, and feeling very tooth and claw indeed. I’d just seen something by Sam Shepard, whose surrealist sensibilities I’d previously loved, but this one involved a young woman recategorized as a teenage sex witch predator of grown men, and I was beginning to find myself wroth about stories of strangely wicked sex witches inhabiting narratives where the adult version of, say, Harriet the Spy clearly belonged. Sick of beautiful girls. Sick of dead girls. Sick of both of those things, and yet. The Bloody Chamber had just been re-released, and had a tower on the cover, and I was ready for new fairy tales with more sex, drugs, rock and roll, basking in language, fucking shit up. Girls beautiful and dead are here too, but they are ferocious, unpredictable, strange, and agented. Carter delivers in utter luxuriance, her work replete to a degree that can seem excessive until you surrender to it. This book is the one everyone reads. I could recommend others, but this one is my beloved life changer. The collection is short, but she grinds her teeth, spits rose petals, and pulls the hearts of dull storytellers out of her minaudiere to make room for the phone numbers of those willing to surrender their pelts. Carter is nasty and sweet at once, and I owe her ghost a good deal of my career.

Song — Brigit Pegeen Kelly

In 2004, before I’d published much of anything, I was at Breadloaf when Kelly was teaching. She gave a reading of poems from this book. I ended up flayed, weeping, awed and starstruck. I was in conventioneer fugue, and yet. The heads of goats sing, orphaned from their bodies. The natural world shrieks, howls, and confides, and tenderness is always cut with fire. All of Kelly’s work is devastatingly beautiful, packed with the sensibility of the classical world made ragingly modern, one part Ovid, one part railroad tracks. The humans in Kelly’s poems are forced to reasonable manners, but they are animal, full of longing, and certainly part of the continuum of beasts. This level of empathy, of a communal story of all the inhabitants of earth, is, I think, tremendously unusual. This book is one I go back to regularly, and I can easily see its path through my own work. I just wrote a mountain with POV, and it is in large part due to these poems. They are tender with teeth.

Mosquito—Gayl Jones

Gayl Jones’ Mosquito is due for not just a revisiting, but a proper visiting. I encountered it sometime in around 2009, on a recommendation from a poet friend after I’d screamed to him for a while about the lack of long ass Important Tomes by women writers, and that if said Tomes existed (Leslie Marmon Silko’s Almanac of the Dead, for example) they’d be categorized as somehow Not-Worthy-Of-Literary-Greatness. Mosquito was published in 1999 to not enough continued fanfare. Jones was roughly 20 years ahead of her audience, as far as I can tell, because goddamn, is America made out of this book right now. It’s infuriating that this book doesn’t appear on lists of Bests, because Mosquito is a pyrotechnic, Joycean longform meditation from the POV of a black female truck driver who establishes an underground railroad across the Texas border. Shall we? Yes, I think we shall. My historic ignorance of the consistent relevance of this story speaks to the lack of support for a spectrum of fiercely poetic and literarily-categorized black women’s voices in the world of novels. Jones was originally edited by Toni Morrison (whose work I’ve listed elsewhere as being a massive inspiration and galvanizer of mine — the braid of the supernatural with bitter reality, the lyric rasp of Morrison’s language — it’s never not astonishing) and often I imagine an alternate version of the history of publishing in which things were vigorously more diverse, in which radical, experimental voices like this one were supported and rewarded regularly instead of once a decade. This is the future I look to, one of long books, one of great books, one I want to pummel into existence. Should this book be categorized as a work of genius? Should Jones be canon? Yes, folks, yes she should. A variety of things conspired against Jones being assessed as the major force she is, and those things are all the usual suspects. This is a Great American Fucking Novel, epic, intense, ferocious, strange, and as deeply about this country as anything I can name. The book is voiced with intensity, and it’s not an easy read, but seriously. Easy read isn’t the goal. Blistering song: what else has this country’s discourse been built from? I have lots of time for voices not rooted anywhere in legends of white masculinity, and this one is like opening your ears to a revelator. It’s brilliant.

The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf—Kathryn Davis

I’m a huge fan of Kathryn Davis’ work, and I love all of her books, which are completely different from one another. She’s such a giant badass, and I have an imagined version of a life in which I add an extra month sandwiched into February, sort of an origami fold of days I might be able to spend in a bathtub reading books. In this version, I’m always beginning with a reread of one of Davis’ books, because they restore my soul. The Girl Who Trod on a Loaf is a strange and surging, haunted friendship of two women — an elderly opera composer and her younger friend and beloved, Francie, a single mother of twins, who inherits her friend’s operas. The composer, Helle, is Danish, and I think I’m especially tempted by Northern narratives (one of my other most-recommended titles is the poet Inger Christensen’s ecstatic and devastating accounting of existence, collapse, and the elements of the world, Alphabet) and the fairytales of hunger, longing, and faith that rise out of them. Helle wills the finishing of her unfinished opera based on a Hans Christian Andersen fairytale to Francie, whose personality reminds me of that of Sylvie the vagabond aunt from Marilynne Robinson’s Housekeeping– basically, I have an ongoing love affair with novels of women’s lives in which the women are unapologetic eccentrics, almost creatures, in their calm refusal to wed themselves to societal norms of partnership. This book is about mentorship and grafting flawed and ferocious ambition onto someone whose circumstances have created lack of same, and it’s just fucking rare and intriguing to read a book like this about women’s lives. Especially one full of imaginary operas based on things like, for example, Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Writing this made me notice that many of the women on this list of writers are or were roughly the same age—Angela Carter was born in 1940, Kathryn Davis in 1946, Gayl Jones in 1949, Brigit Pegeen Kelly in 1951, which makes sense, given that I was born in 1977, just in time for Reagan, but lucky enough to read the work by women writers being produced in the first couple of decades of my life. Their work was shaped by a landscape of feminist theory, abortion rights, birth control, one that now looks very damn shaky. Their characters, largely without exception in this list, had the liberty to be strange, kinky, recalcitrant, unpartnered, bohemian, interested more in the natural world than in the world of men. I think about this now, in the work coming today, and out of this world, and I long for more work like this, more characters with unexpected emotional lives, more oddity braided to the quotidian. The next collection is that precisely.

Tender — Sofia Samatar

This is a short story collection containing wonder after wonder, done with casual intensity. These are all sharp knives of stories, and it’s definitely possible to think oneself unsliced until the blood starts to pour. I encountered Samatar’s short work in 2012, probably, with her short Selkie Stories are for Losers, and was floored on sight. She’s published two novels as well, but the short fiction is my first love. Unlike the rest of the authors on this list, I actually know Sofia, and I’m as moved by her in person as I am by her work. Her wide-ranging and deeply researched interests are fully showcased in her prose, which moves from nonfiction to speculative surrealism, from historical automatons to victims of warfare, all at the same time. There are witch stories, and ripped from the headline stories, stories about longing for other planets, stories about the human condition of pain. They cross all genre divides, and smash them. This collection was edited by Kelly Link, herself a lighthouse of mine, and her work has common ground with Samatar’s, just as both of their work has common ground with everything else on this list. These are all authors whose works are sui generis, but who constitute a tribe of writer warriors as far as I’m concerned. Everyone here is an obliterator of tropes and received myth, a reviser of hierarchy, and a deeply skilled storyteller and maker of worlds. I can’t even believe I get to live in a time in which writers like the ones on this list exist, let alone get to have their brains feed mine.

Read these women.

Read More Women is presented in collaboration with MCD Books.