interviews

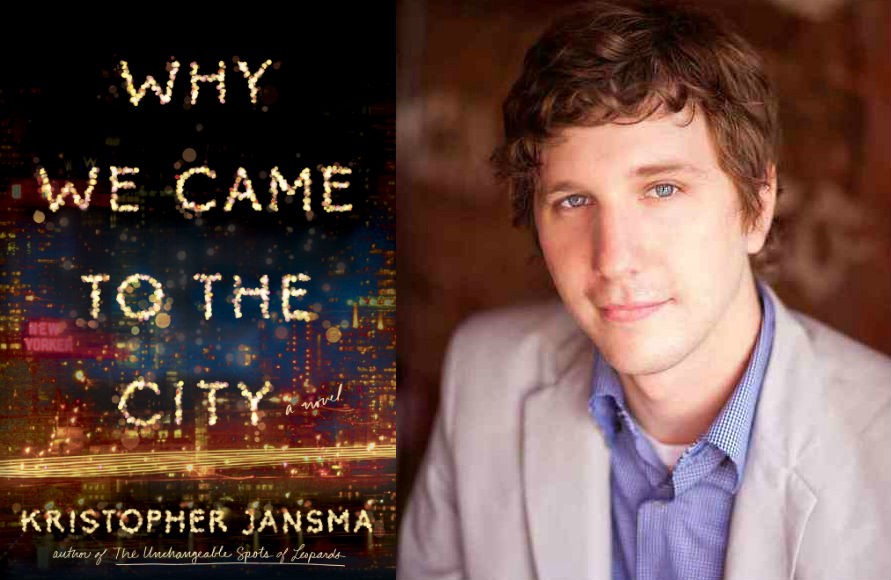

Kristopher Jansma, Author of Why We Came to the City, on Capturing a New York Generation

Nearly three years ago, I met Kristopher Jansma in this exact same Park Slope, Brooklyn coffee shop for this exact same reason: to talk about the release of a book. In March 2013, his debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, was about to hit shelves, and we gathered on a snowy day to talk about the trepidation of letting a first work out into the world. I’m going to spoil this story: Jansma survived the release of the novel, as well as the paperback cycle, to write a sophomore book, which hits shelves in February.

Why We Came To the City (Viking, 2016) is in part the story of five friends who’ve moved to New York, post-college in 2008, dealing with the curve balls that the great city throws at them, their lives ebbing and flowing at the boroughs’ whims. But it’s also part love (and, okay, breakup) letter to the city, rendering Jansma’s own relationship with its tumultuous streets, reminding us just how living and breathing an entity this machine really is — and what it takes to hack it here. That’s certainly something that the author has learned since moving here for an MFA at Columbia after graduating college in 2003, and then planting roots in Brooklyn with his family.

A lot has changed for Jansma in three years since we first met to talk Leopards (although the quality of the coffee here, sadly, hasn’t). That’s where we decided to pick up the conversation.

Meredith Turits: You’re physically in the same place as when we last met, but life-wise, you’re certainly not. What’s the biggest thing that’s changed?

Kristopher Jansma: Having a kid has just turned everything around. That’s shifted all of my priorities, including writing — trying to find ways of being an author and a writer when I’m not being a dad has been really challenging. I was thinking about going through [a book release] this time around and I think I have a better sense of what’s happening and what the stakes are, whereas the first time around you have no idea. So far, I’m not so panicky this time around, which is a good thing.

MT: You’re very active on Twitter. How has the transparency of Twitter and social media in general affected the way you interact with the contemporary fiction space?

KJ: It’s wonderful for talking to readers, and I find that’s something I can’t imagine would have been possible before. Ten years ago, you’d write your book and go to a reading, you might talk to a few people during a signing, and that’s it. And now I can have an ongoing conversation with a random guy who likes my book in the Lower East Side, an interesting person who I can now have a weird friendship with. But there’s the other side of it that can be sort of daunting where you’re seeing everybody else whose job it is to promote their own work or other people’s work complain and talk about how mad they are about this or that. It can be a little intimidating when you start to see how easy it is for certain people to get set off by something. You start to worry, Could that happen to me?

MT: My friend who is reading the book now had a great point where she said that the novel seemed to her more about a generation of people, and less about a specific group. It’s a concept that I loved.

There was always this tension around that that I wanted to capture, too. Everyone always has that one foot out the door.

KJ: I love that. That’s definitely something I wanted to talk about — not just these five characters, but what I’d seen going on with a whole generation or microgeneration. I came here with two friends of mine right after college in 2003, and those were the only two people I knew in New York for, like, two years. And then I watched what happened as we came up between 2003 and 2008. [My now-wife] Leah moved here in 2005, and we started meeting a lot of new people through her work friends in publishing who were very similar — young, hungry, willing to work long hours and put up with lots of crap. There was something so exciting about all of that, and I really wanted to write about that. And at the same time, there were always people who were leaving; people who I thought were wonderful who said, “Fuck it, I’m going to Texas!” or “Get me out of here, I’m going to move to Pittsburgh,” or some place cheaper. There was always this tension around that that I wanted to capture, too. Everyone always has that one foot out the door.

MT: Questioning the sustainability of the city.

KJ: Yeah. How can I make this work? The big thing I thought that changed was when the financial crisis hit. Before that had happened, I thought there had been this maybe naïve belief that everyone was going to just pay their dues and work super-hard and get promoted and rise up from editorial assistant to assistant editor to associate editor to editor to senior editor to running the imprint, and I remember having conversations with Leah’s friends like that where they’d be saying, “In ten years, we’ll be in charge of this whole place!” Then I think what happened was that the people who didn’t lose their jobs were there but they couldn’t go anywhere — they weren’t going to get a promotion. Nobody was going to move over to a different job, and their bosses weren’t retiring, leaving and making space for anyone else, and that totally changed the dynamic. And then more and more people did start leaving because they realized this isn’t going anywhere. So, I really wanted to capture what was happening here at that moment among people in their twenties.

MT: This group of people that you chose to represent, were they supposed to be archetypal?

KJ: The characters definitely weren’t archetype constructions at all. I’d started writing stories about these characters — Sara and George came first, and Irene was sort of in the background — and every once in a while I’d write about a different character who sort of felt like they felt in with these ones. Eventually, I had the people who were going to fit together the best. But I do think each of them shares qualities with people I’ve known over the years. Jacob is the loudmouth, super-confident kind of guy and George is sort of his counterbalance as someone who is very sweet but kind of meeker — I wanted to write about those things. Parts of each of them have drawn from people I’ve known.

MT: I think what’s interesting about them is we watch this relationship between how the city changes them, and how, at times, they change the city in a way. I’m curious about your own relationship to the city and how the city has changed you.

KJ: I think about it a lot. I grew up in New Jersey, about an hour and a half away from here, and I had no relationship with the city. I came on field trips to see Broadway show or something like that once in a while, but my family was not interested in New York at all. I never had any big dreams of living here even when I was growing up, and a lot of people I knew in my town and my high school would routinely go to New York on the weekends — clubs, bars — and I wasn’t cool enough to do any of that. I just had no interest in living in New York ever.

I went to Baltimore, to Hopkins, to study writing, and I got into Columbia for grad school, and that was my only option, so I went there and that was my introduction to living in New York. For the first few years, I really wasn’t a big fan. I never left my neighborhood. I more or less didn’t leave my apartment — I was always writing, and going to class and coming back and writing. On the weekends, I’d go to Baltimore to visit Leah, and that was my whole thing.

But then later once Leah moved here and I really committed to being here, I loved it, and it totally changed me. I started to realize going back that there was this confidence that I’d never had when I was in college — I always saw myself as part of a big group of friends, but never the leader, and my roommates were generally much more Jacob-like. More gregarious. And being in New York — and maybe living on my own anywhere would have done it to some degree — but there’s this ambition and power that kind of comes with that. I remember even charging up the street — I’d go up Broadway from 102nd to 116th and back, that was all I did most of the time — to go from my apartment to Columbia, and realizing at a certain point that I was bustling through these people, dodging around all the slow people on the sidewalk and I thought, Wow, I’m absorbing this energy from the city. Now I’m at the point where I can’t imagine living anywhere else. It’s gotten into my soul. It’s a pretty awesome place to be living. The city gives you a lot back, I think.

MT: What makes someone able to hack it here?

There’s a sort of stubbornness or insanity…that makes you keep on driving at something despite every message to the contrary.

KJ: I don’t know — that’s a good question. There’s a sort of stubbornness or insanity like we were talking about before that makes you keep on driving at something despite every message to the contrary. You have to be willing to put up with a lot of downsides: small apartments, noisy neighbors, those things. I think some people can see that and find it a way to make them tougher and enjoy the rest of it. Others are just not as interested in that. I’ve had friends who’ve been here who’ve left within a year or two years, who couldn’t wait to get out to the suburbs and have a yard and a fireplace or whatever. We’re now at the point where we’re finally starting to talk about that, and neither of us can imagine that.

I never felt like I was [that kind of person] — even in undergrad, I wanted to write a book someday, but I never really had that sense of I’m going to able to do this. It wasn’t until I got here that I could. Which is weird — coming here and seeing how many people there are who are trying to do it should scare you off a bit, but somehow, I thought, I can do this, too!

MT: Did you feel as you were writing that you had any kind of responsibility of how to render the city? And did you worry about your own biases sneaking in?

KJ: Definitely. One thing I worried about was in the beginning, I had plans for this giant, maximalist epic that would get to every corner of the city. I wanted to show the Fulton Fish Market and the Bronx and Staten Island, and have parts of it everywhere, and then I realized at some point that there’s a reason you can’t really do that. I mean, you can write a 900-page novel about the city, and others have very recently, but you can’t try to get your hands around all of it. It really would have to be a book that would show it from a million different angles because there are so many different New Yorks that exist overlapping all the time.

I realized what I can do is write about the New York I know. I can write about what it’s like to be a twentysomething young professional person bohemian-whatever, and I can write about that part of New York. Once it started to focus in that direction, I started hoping it would echo with anyone coming here from any neck of the woods.

MT: And to that point, very few people actually have that holistic experience of New York. New York is too overwhelming, and you have to carve your niche out.

KJ: I remember somebody telling me before I moved here that there were so many neighborhoods and so many people live in a neighborhood and never really leave it. That was basically my experience when I lived in Morningside Heights. There’d be times when I would have to go somewhere else — I’d have a birthday party and have to go to SoHo, or something — and I’d go on the subway and have no idea where I was or how it connected to anything. Even six or seven years later, I’d be walking and think, Oh, this is where that happened! They’d be all of these isolated pockets where, at the time, I had no idea how they happened.

And that was just Manhattan. I didn’t move to Brooklyn until 2010 or 11 — maybe after that. I knew nothing about Brooklyn, and just stayed in Manhattan all the time, and even when I started working on this book, there were all of these snarky, Manhattanite ‘we don’t like Brooklyn jabs’ in there that I ended up taking out because now I live here and I really like it. But it was mostly just because I had no idea where anything was — I’d come over to Park Slope to meet a friend or something and think, Well, none of the streets are numbered so I have no idea how to get anywhere. There are rare people who really do live in the whole city, but many of us just know a part of it. And that’s a lot — even one part of Brooklyn is bigger than a lot of other cities.

MT: What’s your thought on the phenomenon of the “Brooklyn book” right now?

KJ: That’s a good question. I remember when Leopards came out, we had just moved to Brooklyn and I was trying to keep it under wraps. I didn’t want them to put “he lives in Brooklyn” on the back of it, and I remember during interviews, I’d say, “Don’t say I live in Brooklyn.” But now I’m definitely a Brooklyn writer. I hardly go to Manhattan anymore.

It’s the same thing as with Manhattan, though — there are a hundred different Brooklyns. There’s sort of the Park Slope to Fort Greene zone we’re in. I have a friend who lives in Williamsburg, and I feel completely alienated from what’s going on with him. We go up there every once in a while and say, “Wow, this place has really changed since two months ago!” I think there are so many of us living here — it still really is such a wonderful place to live as a writer.

MT: Did you at any point worry or wonder about your reader who was not based in New York and what his or her experience would be with the book?

It can be a great place to be with all of your friends, but it can also be a very lonely place to be when that part of your life has started to change.

KJ: I wanted it to be something that would appeal to someone in other cities — that’s a lot of the reason why certain parts of the book like the prologue and the in-between part have certain details that are specific to New York, but I wanted to make sure that they had a tone that could fit other cities, as well. I wanted to have enough of that in there that it would maybe appeal to people who’d left the city, or younger people who are thinking about moving to the city one day and were dreaming about it. I’ve had interesting conversations with people who’ve read the book who used to live in the city but left because they didn’t like it, and I think it’s pretty interesting in that sense, too — if you become a city-hater, if you read the book, you wonder, What’s wrong with these kids that they like it here so much? I think the book ultimately turns on them as they stay there longer, and some of them end up leaving. It can be a great place to be with all of your friends, but it can also be a very lonely place to be when that part of your life has started to change.

MT: Do you think that if college Kris had picked up this book before deciding whether to move to the city he still would have come?

KJ: Yeah, I think so. I do. I think college Kris would have been encouraged by that because I remember thinking at the time that I’d lived in Baltimore, and that’s a city and not necessarily a super-easy one sometimes, and that I’m used to dealing with city stuff and getting around with public transportation and not getting mugged and stuff like that. Then I moved to New York, and realized, wait, this isn’t a daily reality. I think it would have been encouraging. I would have felt like there was a road map, at least, of how to get the most out of it.

MT: So, what’s next?

KJ: I’m working on something new. I can’t say a whole lot about it yet, but like this and like Leopards, it’s also growing out of some stories I’ve been writing. I’ve been writing a lot more trying to figure out family and my son, and I’ve been trying to figure out how to incorporate that into what I’m writing because as sad as I am about it, I’m not living this city life anymore — I’m not going out with my friends and having fun at a bar very often. We had to meet at 9:30 at night after Josh went to bed — this is a big night for me! I’m trying to figure out how to write about that a bit more, so the next thing will be about family, and about one thing that I’ve been thinking about as we’ve started a new generation, which is how much the things in my life already affect him in his life in ways that I wouldn’t have thought. Then, thinking back, how much of my parents’ stuff when they were my age was affecting the way I grew up and the way I saw things.

MT: And I have to ask: Is it going to be set in New York?

KJ: No. If it goes the way I think it will, most of it will be set it New Jersey, which is where I grew up. I’m thinking about trying to write about that again. Although, now as a New Yorker, I don’t ever want to live in New Jersey again. I’ll live anywhere else, but there’s a certain pride I have over escaping New Jersey.