essays

Late to the Party: Stephen King’s IT

Reading the master of American horror for the first time

Editor’s Note: Late to the Party is a new Electric Literature series where we ask writers to read an author that, for some reason, they’ve never read.

PART 1: THE SHADOW BEFORE

Stephen King was the puppet master of my literary childhood, but I haven’t read a word he’s written. His heavy hardbacks lined the shelves of every adults’ room, even at our old family farmhouse in south Alabama, spines advertising King’s killer car, his killer dog, his killer… you know. King belonged to my parents, to my grandparents. I was a kid during the Goosebumps/Fear Street boom, so that brand of King-biting (but toothless) scare was marketed straight at me and fulfilled my need for anything labeled “horror.” And when I turned ten and ready for popular adult fiction, I grabbed Crichton instead. I grabbed Grisham. What was wrong with me? Fear, probably. I wasn’t ready for true horror.

What I couldn’t avoid were the movie adaptations, mostly viewed late at night during slumber parties, through hands half-covering my eyes. Carrie, The Shining, Misery all became touchstones for understanding King’s oeuvre. His stories crept into my nightmares, and into my writing. But I only truly became an admirer when I watched 1986’s Stand by Me as a teenager. In contrast to The Goonies, it was naturalistic and profane, dark and resonant and obsessed with death, despite being set in a bygone era. I wanted more of this kind of King, and have no idea why I never watched the 1990 miniseries IT, or cracked the book itself, which promised a kid gang journey into a cosmic terrordome, the anti-Goonies.

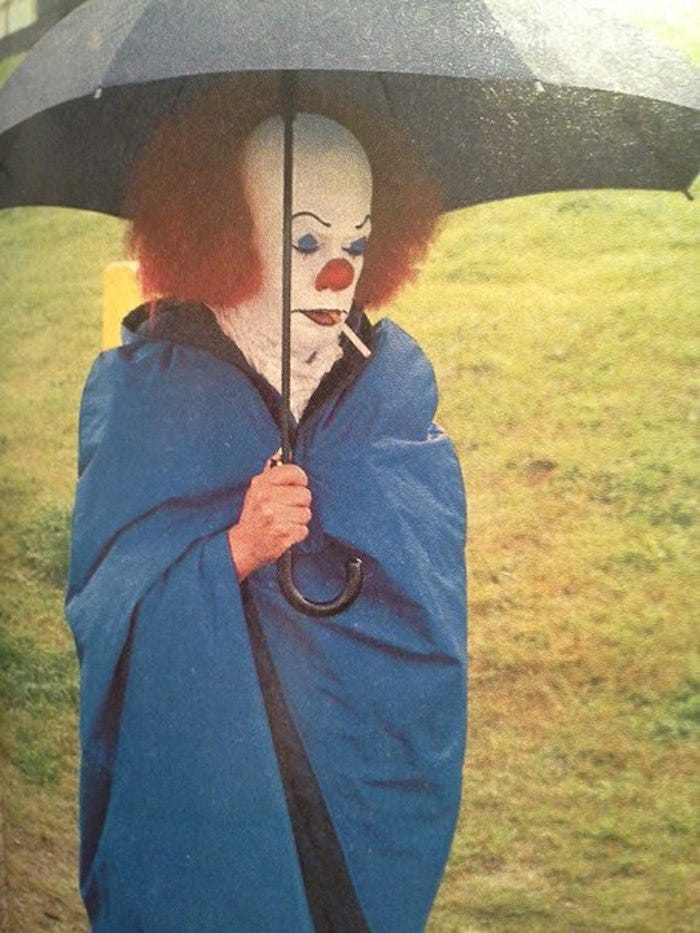

IT: the most daunting of King’s work on those adult shelves, the largest book with the shortest title. The cover didn’t reveal what the monster was. I only found out later, during my Tim Curry phase, that there was even an evil clown. I get why a lot of people are afraid of clowns, but I’m not one of those people. For a solid two months of high school I was a straight-up Juggalo. I used to have visions that a clown was standing in the doorway of my childhood bedroom, but it was facing out, not in, protecting me.

And now the nostalgia market is pushing King back to the forefront of pop culture, if he ever left. IT is being remade as a feature film. The remake should have the Stranger Things audience on lock, and even stars one of those same child actors. Stranger Things itself is arguably the most blatant King rip-off since The Sandlot. So I feel obliged in this era of diminishing returns to go back to the source.

I bought IT. I’m going to marathon all 1,153 pages of IT. I have never been more excited to devour a famous novel. Send in the motherfucking clown.

PART 2: AN ARTERIAL SPRAY HOME COMPANION

Oh god I am so scared.

The opening chapter does a masterful job of situating me right in the center of little Georgie Denbrough’s world, laying out his small joys and his relatable fears in 1957, and then forcing me to experience his brutal murder first-hand. The child’s perspective warps the world, making it even more eerie and horrific when Pennywise the Dancing Clown appears in the storm drain. This is a virtuosic, “master of horror” set piece, and I can see why it’s the most iconic scene. After Georgie’s fatal encounter there’s a stirring meta-textual passage about the journey of his paper boat. I hold the full heft of IT in one hand and imagine the many, many child killings that are sure to follow. The spine breaks.

This book is huge and it’s clearly not about a killer clown. It’s about something much worse. The clown is the comforting element, the lure.

The second chapter starts what I’ve heard is a central trend in King’s writing: the subverted small-town pastoral. In zooming out to the wider world of Derry, Maine, and detailing the many angles of a mysterious hate crime in the “present”(mid-1980s), he immerses me in the mindset of local characters, propelling me along with them at the pace of Derry, learning its geography, history and quirks. Like Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon but with mutilations.

This book is huge and it’s clearly not about a killer clown. It’s about something much worse.

If the initial terrors hadn’t frightened me away as a kid reader, the following hundred pages would most likely have been an impassable moat. These 1985 segments introduce a gang of Derry-bred adult professionals, Baby Boomers who’ve long left and long forgotten their horrific hometown. They each receive a triggering phone call from their long lost buddy Mike, who still lives in Derry. I would not have been into this when I was younger. I wasn’t afraid of clowns but I was afraid of adulthood, and the general depression here would have confirmed my fears, as would the domestic violence. King writes a whole chapter from the POV of Tom, the abusive misogynist husband of main character Beverly, which serves as a sadistic, effective complement to the fantastical. This is a good horror tactic, placing me squarely and exhaustively in a moment that turns demonic or fearful, awash in unpleasantness. But these early sections are also long and segmented, taking forever to arrive places, word-wise. There are a handful of unfortunate witticisms that King repeats twice, one at the expense of a large woman, another has a childless wife observing the drip from a faucet as “pregnant,” again, twice. As an adult reader I’m weighed down.

However, the tedium of these “getting the band back together” sections benefits the novel as a whole, because now I’m raring to return with them to Derry, to their childhood nightmare, as soon as possible. Doom be damned.

PART 3: THE GOOSEBUMPS SLOWLY MELTED AWAY

“My candle burns at both ends;

—Edna St. Vincent Millay

It will not last the night;

But ah, my foes, and oh, my friends-

It gives a lovely light!”

—Manfred Mann

“Do wah diddy diddy dum diddy do.”

^ King opens each of IT’s parts with a quote pairing like that. I have a soft spot for bloated, flawed masterpieces. I welcome these flourishes.

Once the story shifts to the summer of 1958, I’m all in. Here’s the demonic kid-world I was promised, and King’s is real as hell. And by real I mean categorically dangerous, full of dread. The Losers Club is a group of victimized youth, an ambitious squad of outcasts. Bill, Ben, Eddie, Richie, Stan, Beverly and Mike: seen as weak and vulnerable by adults (stutterer, fat, asthmatic, four-eyed, Jewish, female, and black), and terrorized by their sociopathic peers.

The monster in IT feeds on local kids (and possesses local adults) by manifesting as their fears. It’s a striking conceit for long-form horror, because every chapter shifts perspective, and in each kid’s perspective IT becomes the exact thing they fear: werewolves, gigantic birds, relatives both dead and living. Each new sequence is psychologically exhausting and I’m gripped.

Stan, the one character who commits suicide rather than face IT as an adult, is given this remarkable Lovecraftian passage after he encounters walking child corpses and Pennywise in a standpipe:

He wanted to tell them that there were worse things than being frightened. You could be frightened by things like almost having a car hit you while you were riding your bike or, before the Salk vaccine, getting polio. You could be frightened of that crazyman Khrushchev or of drowning if you went out over your head. You could be frightened of all those things and still function.

But those things in the Standpipe…

He wanted to tell them that those dead boys who had lurched and shambled their way down the spiral staircase had done something worse than frighten him: they had offended him.

Offended, yes. It was the only word he could think of, and if he used it they would laugh- they liked him, he knew that, and they had accepted him as one of them, but they would still laugh. All the same, there were things that were not supposed to be. They offended any sane person’s sense of order…

…You can live with fear, I think, Stan would have said if he could. Maybe not forever, but for a long, long time. It’s offense you maybe can’t live with, because it opens up a crack in your thinking.

The small triumphs of the Loser’s bonding peel away to the malicious weight of their imaginations, to fear itself, of life leaving. They share stories of trauma at the hands of IT, all harrowing, convincing bonding. Their outsider status and bookishness becomes a boon when they do library research and culturally appropriate ancient rituals to learn what IT could be and strategize IT’s destruction.

I’m also a sucker for narrative depths, so when IT is revealed to be a prehistoric inter-dimensional entity, hell-bent only on “feeding,” my reading pace accelerates. The adults reunite and tour the town, accessing their lost memories (as flashbacks), and the 1958/1985 simultaneity finds cohesion here, the trauma and repression of youth underscoring the plot.

An old co-worker of mine once told me that as a child he was part of a strange global phenomenon that occurred during the theatrical release of Steven Spielberg’s E.T.- The Extra Terrestrial: many kids, especially those around 8–11 years old, would immediately vomit upon exiting the theater. Because Spielberg had filmed E.T. from a child’s perspective, orchestrating the shots at main character Elliot’s height, those kids in the audience were experiencing acute motion sickness and withdrawal after the movie was over. This seems to be at play in IT as well: the adults have their visceral kid memories crashing in on them, pulled forward and backward in time, and I experience it alongside them, to nauseating effect.

HENRY: THE FIRST (AND ONLY) INTERLUDE

I have this book’s blood all over me.

IT’s subconscious influence is undeniable in the haunted childhood stories of my own books. The first part of my debut prominently features spiders and storm drains. Any writers exploring the horrors of childhood imagination, the nascent poison of reverie, are indebted to King, apparently even if they haven’t read him.

I appreciate his juvenile truths, especially in this all-but-thesis statement:

Kids were always almost getting killed. They dashed across streets without looking, they got horsing around in the lake and suddenly realized they had floated far past their depth on their rubber rafts and had to paddle back, they fell off monkey-bars on their asses and out of trees on their heads.

[…] kids were better at almost dying, and they were also better at incorporating the inexplicable into their lives. They believed implicitly in the invisible world. Miracles both bright and dark were to be taken into consideration, oh yes, most certainly, but they by no means stopped the world. A sudden upheaval of beauty or terror at ten did not preclude an extra cheesedog or two for lunch at noon.

But when you grew up, all that changed.

PART 4: INEDIBLE MUTANTS

“Why does a story have to be socio-anything? Politics… culture… history… aren’t those natural ingredients in any story, if it’s told well? I mean…” He looks around, sees hostile eyes, and realizes dimly that they see this as some sort of attack. Maybe it even is. They are thinking, he realizes, that maybe there is a sexist death merchant in their midst. “I mean… can’t you guys just let a story be a story?”

—Bill Denbrough (King’s closest fictional analogue here) in a college writing workshop

There’s this decaying Boomer ideology happening in mid-80s popular narrative art, also prevalent in the work of David Lynch. The idea that the small town idylls of white capitalism had an underpinning of supernatural decay, an original American “evil.” There’s a direct parallel here between the cosmic creature IT possessing “dogsbodys” and the envoys of the Black Lodge from Twin Peaks. Especially when Beverly is accosted and stalked by her abusive father/IT in a similar way to Laura Palmer’s assault by her father Leland/Killer Bob in Fire Walk With Me. The fundamental evil stands in for the systemic poison of masculinity and misogyny.

Whereas Lynchworld is largely whitewashed/race-avoiding, King is consistently frank about racism. There seem to be as many instances of the N-word in this book as there are in Huckleberry Finn. The word erupts from the world of Derry, and swarms Mike Hanlon, fictional author of the book’s interludes, town librarian and singular black man. His white supremacist bully screams the hate word at him in childhood and adulthood, while threatening his life, but Mike’s best buddy Richie also performs minstrelsy by way of his character impressions.

In King’s world, this racial violence is pivotal. Mike, who understands most deeply what it means to be a body at risk in the white town, from childhood on, is the one to bring everyone back together and remind them of their promise to vanquish evil. Supernatural horror becomes a Trojan horse for explorations of prevailing societal violence. The original evil lurks below the surface, in the sewers. In contrast to Stranger Thing’s upside-down, King’s subterranean/inter-dimensional evil has infected everything, consuming and spellbinding the town itself.

The vacillation of adult/kid experiences becomes symphonic in the later parts of the book, and the payoff is two climactic battles at once. The Losers are forced to remember how they beat IT in 1958 so they can destroy it in 1985. Because King has acclimated me to the childlike perspective, I’m flexible and open to the celestial ballet, the turtle-god, and all the other stretches that occur.

I’m also fully convinced that IT is an unfilmable novel. The prose manipulates, stunts and relies on the reader’s imagination to such an extent that any filmic image of the horrors would be somehow disappointing or wrong. There’s an impossible physicality to so many scenes, especially towards the finale. Only the cerebral act of reading seems sufficient to conjure these visions. This is the true test of a vital literary work.

And speaking of unfilmable:

PART 5: THAT

That scene.

It would be weird to not write about that scene.

PART 6: THE SINS OF AN ENDING

I was warned that King isn’t great with endings.

Although I was totally swept along through the showdown, I’ve got one final clown bone to pick: Why does the cosmic evil have to be gendered at the 11th hour? In a similar twist to the film Aliens, released earlier in the same year as IT, the adult Losers discover that their nemesis is not only female but has also reproduced and is surrounded by eggs primed to hatch. Although the broader horror of Aliens is egregiously built around fear of the female body/reproduction, there’s a synchronicity to that film’s ending because of Ripley’s parental connection with Newt, and the crucial fact that she’s a female protagonist.

In King’s book Beverly sits the fight out in order to clutch the fallen Eddie while the three remaining dudes chase IT (in giant spider form) to the nest, now allowed the ugly catharsis of screaming “bitch” as they decimate IT and IT’s spawn. I could almost make sense of, and potentially forgive, this unnecessary twist if IT’s feminine form was a reflection of the male Losers’ deep-rooted fear of female power, but the gender revelation occurs first to Audra, Bill’s wife, and then is somehow set in stone as the creature’s physiological truth.

That said I like how even though the Losers are victorious, Derry is all but destroyed in the wake of the battle. I like the line “Steven Spielberg eat your heart out.” I like how the book is over.

IT feels like an ultimate expression from King, unfettered and expansive. At the moment I feel exhausted by his authorial presence and can’t imagine having the desire to read more in the near future. But I’m certainly curious, what the hell is Carrie like?

EPILOGUE

“You can’t be careful on a skateboard, man.”

As I coasted downhill through the happy endings of IT this line kept rolling through my brain, spoken to adult Bill by a random boy he encounters. A perfect line, I thought, to use as a title for one of my essay sections. Terse, resonant, clever. Then King returns to this line again, and even uses it in the header for his own epilogue. He knows its value, dammit. I never knew until I looked up his personal life for this piece what a severe drug problem King had throughout the 80s. Whole books, like Bowie albums, written in hazes and then blacked out of memory. The forgetting. I understand. Maybe the real horror here is being a writer, to have so much grotesquery in your head that you have to constantly channel it onto the page and into the collective unconscious. This seems fundamental for King, the nature of the beast. It’s not a cushy, safe profession; it’s waiting around the corner of every day, under the cover of a notebook, waiting to consume you. You can’t be careful on a skateboard.