Interviews

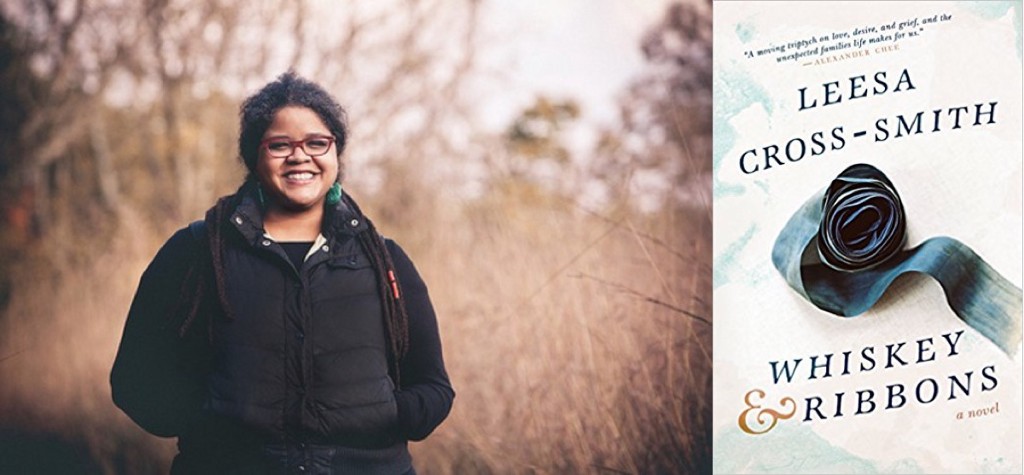

Leesa Cross-Smith is Taking Back Kentucky

Her charming debut novel shows there’s more to the state than hillbillies, country music, and horses

Leesa Cross-Smith started her writing career composing obituaries for the local newspaper. She has since changed her focus, from the departed to the fictional, but her ability to encapsulate a life in a couple of sentences still serves her well.

Cross-Smith’s debut was the story collection Every Kiss a War (Mojave River Press, 2014). Her upcoming novel Whiskey and Ribbons chronicles the relationship between Evangeline (Evi) Royce, a ballerina, Eamon Royce, her police officer husband, and Dalton Berkeley-Royce, Eamon’s adopted brother. When Eamon is killed in the line of duty, Evi and Dalton are left to cope with their grief. Whiskey and Ribbons recounts a timeless story of love, grief, resilience, and family set against the backdrop of modern Louisville.

Cross-Smith’s work has received Editor’s Choice in Carve Magazine’‘s Raymond Carver Short Story Contest and been a finalist for both the Flannery O’Connor Short Story Award and the Iowa Short Fiction Award. Her work has appeared in Oxford American and The Best Small Fictions 2015, among many others. She is also the founder/editor of the literary journal WhiskeyPaper.

Cross-Smith and I took some time to talk Southerner to Southerner about misconceptions of Southern African-American life, delayed gratification, and hip-hop in Louisville.

Latria Graham: There’s a 20-year arc between when this story was started in school, and it’s publication with Hub City Press. Can you talk a bit more about Whiskey and Ribbon’s origins and how it developed?

Leesa Cross-Smith: I started it when I was in college. Originally it was a simple story about a woman who was torn between two brothers/adopted brothers/best friends.

A local police officer in my town was killed right after my daughter was born. I started thinking about his widow and how her life looked now, and felt now, and I was so touched by it just because those things always affect me but because I just had a baby and I was so dependent of my husband. I just couldn’t stop thinking about that and tying that to the story I started in college. You’re always encouraged in writing to dig into those really dark places. I was compelled to continue working on it, so it just kept coming back to me. I made it a short story, and then I couldn’t stop thinking about it, so I just kept writing it and made it a novel.

LG: I was listening to the Spotify playlist that accompanies the book. There’s classical, there’s country, there’s the Grateful Dead in this lineup. Even the way the novel opens is musical. What does music do for you as a creative?

LCS: I always make playlist to everything I’m working on, so it’s always been something that I do, whether I’m assigning a song to a specific character, or creating a mood. So I’ll always have something in mind to create a mood, or I will say to myself, “I want to write a story, like how this song makes me feel.”

LG: What role did you intend for music to have in the novel?

LCS: Originally I had no idea how to structure this novel. It drove me crazy. I would go on long walks, I would walk three miles. I would just think about it, and I couldn’t, I absolutely could not figure out how to structure it.

While reading, I came across the idea of a fugue, which is defined as a piece of music that intertwines several different voices, some of them repetitious, and then a voice drops out. That’s exactly what I needed to do when I was putting this book together. I have their voices come together as if they’re all singing a song, and then we have Eamon’s voice drop out.

While reading, I came across the idea of a fugue, a piece of music that intertwines several different voices, some of them repetitious, and then a voice drops out. That’s exactly what I needed to do when I was putting this book together.

LG: Everybody thinks of Kentucky, musically, as a country music kind of place. I don’t know whether or not you agree with this, I see the state as a middle ground for music — where rock, bluegrass, country, hip-hop and blues intersect.

LCS: We have so many dope hip hop artists here in Louisville. There’s rock, and there is a lot of bluegrass, and then there’s a lot of punk bands in the 90’s, and a lot of alternative music and stuff like that. My Morning Jacket is from here, and they’re super alternative. Kentuckians know how much diversity there is, but then people in other places, yeah they will ask if we ride a horses.

Louisville is a big city. A lot of people don’t really know that, but in Whiskey & Ribbons, what I’m trying to show is that there’s Black people who live in Louisville and it’s wild, but yeah, they get married too. They go out to dinner, they go to work, they own businesses. There’s black people here, you know, dancing and listening to music. And they get in fights, and they have sex, and they get hungry. Eamon is a Black dude and he listens to Grateful Dead.

LG: What do you wish people understood about the Kentucky?

LCS: There are people here existing in that middle space. It’s just a matter of listening, which I think a lot of people don’t do, especially in this climate. So there’s a lot to say there but I think it requires a lot observation, which people aren’t that good at. It’s easier to make snap judgements, or rely on what you see on television if you’ve never been to a place — the way people think California is all about surfing.

Stop Dismissing Midwestern Literature

LG: I understand that this may be more of a craft question, but when reading the book I realized that a lot of the power in this novel was gained by the restraint — not saying too much, letting glances and touches linger instead of spelling them out. How did you know which moments to prune and which you should allow to bloom?

LCS: I cut everything about the kid who killed Eamon, because that wasn’t important to me. It really is just an isolated, random act of violence. There’s so many people in families that have to deal with that. They don’t have the answers. There’s no court case. The kid is also deceased now. There’s just nothing else to say. It’s just a tragedy. So that’s something I stripped down a lot and took outside completely.

In terms of allowing sections to bloom, when I talked to my editor, I really thought really hard and wanted to make sure what we had in there were a lot of the really comfortable, intimate moments between Evi and Dalton when they’re snowed in together. I wanted it to be so confessional, and they know each other so well, but then there’s intimacy there that has not been breached out of respect. Creating that intimacy was important to me. And one other part, in terms of blooming was allowing the reader felt Evi’s jealousy and anxiety she has about Dalton potentially being in love with another woman.

LG: I know you draw inspiration from your surroundings but what helps you keep going when you’re in a real rut?

LCS: I’m stubborn. I am, for lack of a better word, a finisher. I feel blessed because I’m really easily inspired, if that’s a term. I’m really easily inspired. I can see a man’s cuffs on TV, or the way someone steps out of their house, or something like that, and I’ll get a story I could write from that. So it’s really not the inspiration, it’s just keeping in the flow of it that’s hard. The publishing business is designed to break you down, designed to make you want to give up. I have this desire to dig in and be like, “No, I said I was going to finish this, I’m going to finish it.” I’m okay with letting things go if I know they’re not working or something but Whiskey & Ribbons would not let me go.

The publishing business is designed to break you down, designed to make you want to give up.

LG: I know the internet literary community helped you with some of those moments — you’ve been very candid on Twitter about what goes into your writing and what it took to make this debut novel happen. What did the internet literary space do for you at the start of your writing career?

LCS: The internet is how I learned. I was not a part of an MFA program. I did not have my MFA because I couldn’t afford it. And so I really just would see that people in MFA programs are reading like a craft book, and then reading a book of short stories, and I’d go and see where they got published, and I would go to those literary magazines and see if I liked their stuff there. And if they did, I would send them my stuff. And that’s kind of where I started. So I started reading a lot of what people were writing and then when I loved it, I would write them immediately and be like, “I loved this.” My husband and I started our own literary magazine. And so that really helped a lot. I made a lot of connections, and ended up connecting with the man who published my short story collection, through Whiskey & Ribbons. And so I made a lot of connections that way because then I got to spotlight people, which I feel far more comfortable doing than the spotlight being on me. I wanted to add something positive. I really do think that kind of community is what you make it.