Craft

Let Us Now Praise Famous Short Story Writers (And Demand They Write a Novel)

By Amber Sparks

Google almost any celebrated short story writer — George Saunders, Kelly Link, Alice Munro, Isak Dinesen, Joy Williams — and you’re likely to see the same two words over and over again: “writer’s writer.” Lest you be tempted to exalt that phrase’s use, consider Cynthia Ozick’s description: “Every writer understands exactly what that fearful possessive hints at: a modicum of professional admiration accompanied — or subverted — by dim public recognition and even dimmer sales.” Other words might be “underrated,” “under read,” even “obscure.” Ask your co-workers who Lorrie Moore is and watch the blank stares you get in return. Click over to Goodreads and check out some of the reviews of short story collections, and you’re likely to get comments like “I wish he’d write a novel,” and “I just hate short stories.”

As a short story writer, I lived in denial for years. I pretended that the editors were all wrong when they said that short story collections don’t sell, that the Goodreads comments were sullen outliers. After all, most of my friends loved short stories! Never mind that most of my friends were writers, and when I told non-writer friends that my book was a short story collection they were congratulatory but fervent in their expressed hopes that I would someday, finally, write a novel. I did, one sad afternoon, suck it up and start asking people — non-writers — whether they read or enjoyed short stories, and after that proved too dispiriting I took to the internet and read lots of reviews and comments and criticisms and understood, finally: It’s all true.

Most people really don’t like short stories. And that includes lots of critics, who often seem to regard short story collections as a warm-up for the real thing. (Don’t believe me? Look up how often a writer with one or two short story collections under her belt gets called a “debut writer,” when her novel comes out — and how often said novel gets called “her first book.”) If you’re thinking, sure, sure, the public hates short stories, but they win lots of awards and respect! then you should probably go ahead and search for “awards for short story collections” online.

Go on. I’ll wait.

See what I mean? That doesn’t mean collections can’t and don’t win awards (a collection won the National Book Award in 2015, for example.) But they certainly don’t win nearly as often as novels do. When Alice Munro won her Nobel Prize, it was the first time in over a century the prize had gone to someone known for writing short stories primarily.

This is not, by the way, a new phenomenon. There’s a reason so many short story writers headed to Hollywood to make their living, even in the first half of the last century. John Cheever back in 1969 was bemoaning the underdog status of short stories, calling the short story “something of a bum.” Though I’d argue he was always a better short story writer than a novelist, he wanted to stake his reputation on his novels. And he’s not unusual. Take Kafka — he published mostly short stories in his own lifetime, and yet the unfinished novels he left behind seem what he’s better known for — in addition to “The Metamorphosis,” a short story often billed as a novella or even a short novel.

I’ve seen many excellent short story writers make the inevitable and expected career move from short stories to novels, because they want the accolades and the acclaim and the wider audience/money/fame, too. And who can blame them? If you don’t move to novels, you risk looking like a small or unambitious writer or worse, a one-trick pony. Some really do want to write a novel, and some write great ones. Some clearly don’t have their heart in it, and the novels — even if technically perfect — don’t have the soul and the urgency of the short fiction they write. Sometimes critics acknowledge this, and often they don’t.

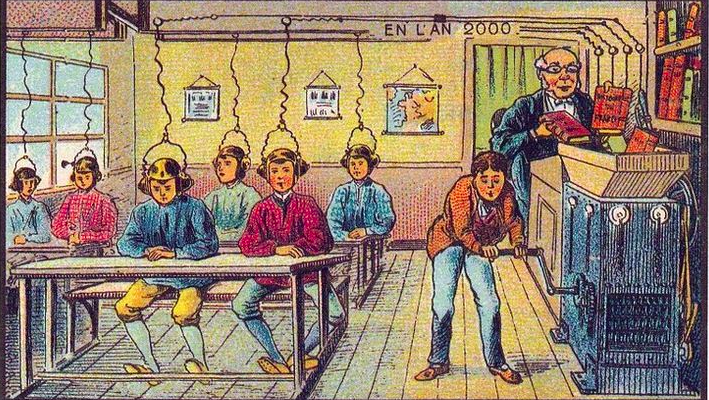

But WHY is this the case? Short stories have been around forever, of course, and many of our modern tales have their roots in the fairy tales and folktales told hundreds of years ago and collected by the Grimm brothers and Charles Perrault, among others. And as Anne Therlault points out, “One need only look to the sources cited by the great folktale and fairy tale publishers from the late seventeenth century all the way through to the early nineteenth century (a time when readers, editors and publishers showed renewed literary interest in both fantastical stories and traditional storytelling) to know that women were, by and large, the main collectors, keepers and tellers of these tales.”

Is the short story seen as a womanly art form, tamed and domestic, slight compared to the doorstop novels of the most well-known male novelists? Alice Munro has said that after some success publishing short stories, she fell into a depression because she couldn’t write a novel, the way she felt she was supposed to. “I had simply lost hope, she said, “lost faith in myself…I guess it was because I still wanted to do something great — great the way men do.” The Vancouver Sun ran a piece about her titled, “Housewife Finds Time to Write Short Stories.”

Aside from gender stereotypes, the novel is exciting, transcendent — the novel is the avatar of burning American ambition. The search is always on, the articles are always being cranked out about the next great American novelist. But what about the next American short story writer? We produce so many excellent short story writers here; why don’t we celebrate them the way we ought? Nabokov knew it. In 1972, he said “at the present time (say, for the last fifty years) the greatest short stories have been produced not in England, not in Russia, and certainly not in France, but in this country. Examples are the stained-glass windows of knowledge.” (And by the way, he greatly admired Cheever’s short fiction, too.)

Since then, the proliferation of MFA programs, the internet, the flourishing of new presses, and a thousand other factors have produced more excellent American short story writers than ever before. Look at the many excellent collections to come out in just the last few years, many on small presses — and look at something like the Wigleaf 50, which every year produces a sampling of the finest short short fiction around. Too, the explosive growth of those much maligned MFA programs has produced a larger audience, if only slightly, than ever before — writers trained in the writing and reading of short stories, ready to appreciate and love the form for what it is. Why do we then ask that these writers become novelists? Surely we have enough of those already?

I’m not sure, having spoken to many non-writers (including many avid readers) that the market will ever support a plethora of commercially successful short fiction. Readers cite the lack of time or interest in constantly immersing themselves in new situations, new scenarios, new characters. They cite plot over character, which will always favor the novel. They say if they’re going to read, they’d rather invest than dip in and out. And of course, mainstream magazines continue to die out and lose readership, and fewer and fewer feature fiction in their pages. So possibly, short story writers are doomed to remain “writer’s writers,” and that might be the problem we really have to solve: how do we assure that short story writers can feel free to pursue their craft without the pressure to move into another, longer form?

Poets don’t have this problem — we don’t tell poets to quit writing poetry and move into short stories already. And maybe poetry, or even visual art, is where we should look when considering short story writers. Maybe we should support short stories not as the cash cows they never will be, but as a vital and necessary art form that we wish to preserve. Maybe there could be more support for short story writers, more awards, fellowships, grants, and showcases. Maybe critics could review short stories collections the same way they review novels. Maybe Time Magazine could occasionally feature the next great American short story writer, whoever she or he may be. Maybe there could be more financial support for, a wider distribution of, the kind of literary magazines that publish top notch, innovative short fiction. Maybe high schools could teach more than the same five short stories (sorry, Updike) so that kids could learn to love the form early on.

Some of this is already happening. Every few years we claim a renaissance in short fiction which is at least partially true, and I like to think that more online publications, more innovative publishing ideas (using Kickstarter to fund projects, for example) — more access, in particular — has led and will lead to a wider readership for short stories. As a reader and writer of short stories myself, of course I’d love that to be true. But honestly, I’d just be happy if people stopped asking “when are you going to write a novel?”

About the Author

Amber Sparks is the author of the short story collection May We Shed These Human Bodies, and the co-author (with Robert Kloss and illustrator Matt Kish) of the hybrid novel The Desert Places. You can find her most days @ambernoelle and some days at ambernoellesparks.com.