Books & Culture

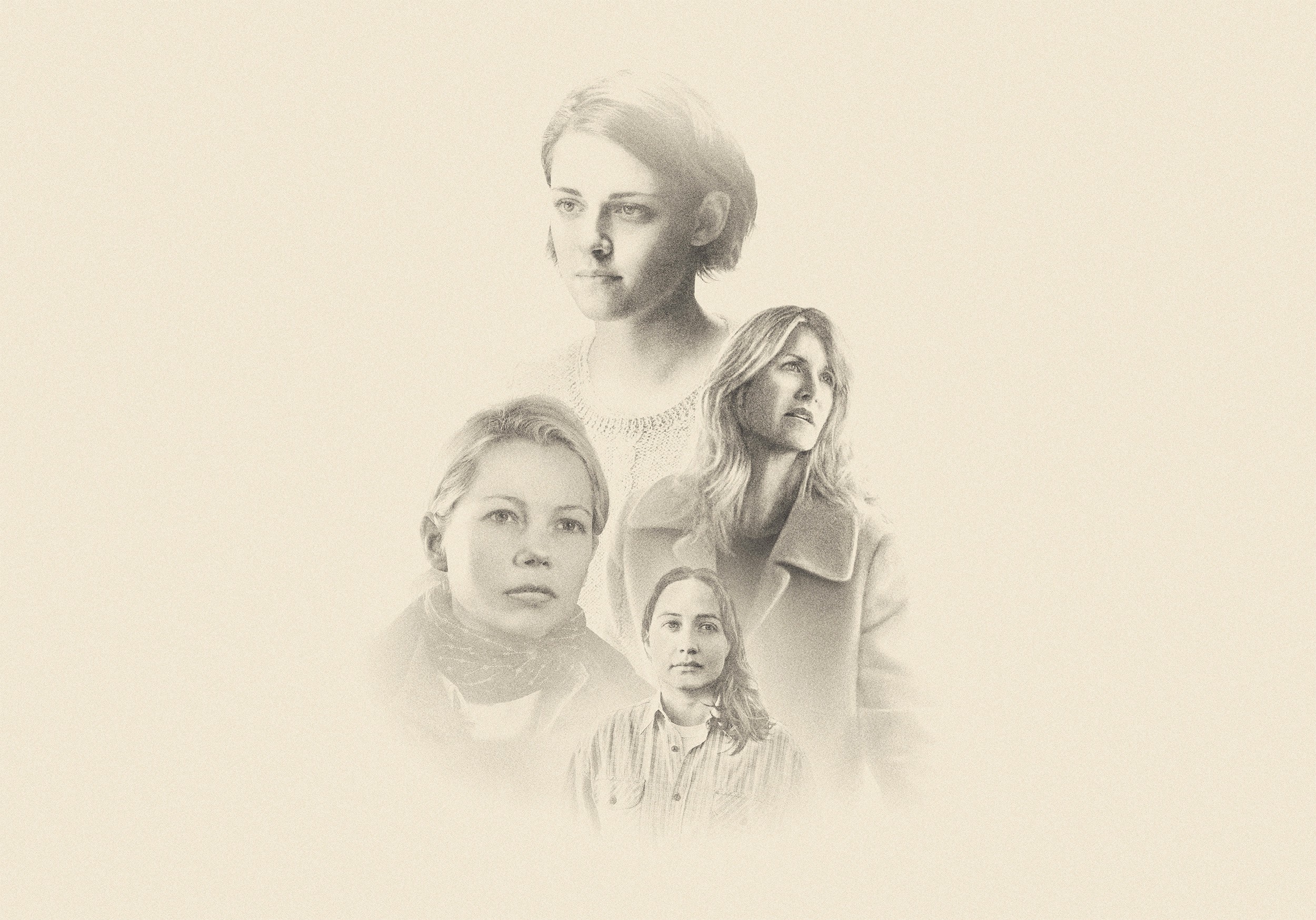

Life Happens in the Pauses: Kelly Reichardt’s “Certain Women”

On the film adapted from Maile Meloy’s “Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It” and “Half in Love”

“She’s interested in the life that happens in the pauses.”

Laura Dern was speaking at a New York Film Festival press conference, following the screening of Kelly Reichardt’s new film Certain Women (2016), and describing what she admired about the work of that minimalist indie director. But she could just as easily have been referring to Maile Meloy, the author behind the three short stories from two of her collections, Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It and Half in Love, which Reichardt brought to the screen in her Montana-set triptych film adaptation. In a New York Times review of Meloy’s collection the novelist Curtis Sittenfeld noted that what distinguished the work of the Montanan author was her restraint: “She is impressively concise, disciplined in length and scope. And she’s balanced in her approach to character, neither blinded by love for her creations, nor abusive toward them.”

The same holds true of Reichardt. As in her earlier films (all of which she co-wrote with Jonathan Raymond; this is the first she’s done solo), Certain Women is attuned to the smaller moments of life. The trio of narratives studiously observe the women they’re centered on without feeling voyeuristic, and she makes her camera (and by extension, her audience) empathize with the characters without demanding identification. Her frame is intimate yet never intrusive, catching the quietest, most telling details of the people we’re invited to meet.

Among them is Dern, who plays a small-town lawyer named Laura Wells. We meet her at first in a messy bedroom, where she has found refuge in the middle of her work day with a man now putting his clothes back on. Lingering longer than she should she finally gets dressed and heads back to the office, although, in her hurried state she only half-tucks her sweater into her skirt — a detail Reichardt’s framing encourages us to notice but without making it explicit.

Reichardt’s focus on these interstitial pauses functions as a visual conjuring of Meloy’s free indirect discourse, allowing moments that might otherwise be excised — because they don’t strictly advance a plotted narrative — to linger, stressing the way that our most obvious attempts at introspection happen not when staring out a window or furrowing our brow, but in the most mundane chores of everyday life. When Laura takes her client to hear a second opinion from a lawyer in a neighboring town (who repeats what Laura has already told him: there is no tort claim to file against his former employer, after the accident that’s left him physically and psychologically disabled), we can see the frustration in her face for the way her authority has yet again been undermined. We don’t need Meloy’s words — “I thought, That’s what it’s like to be a man. If I were a man I could explain the law and people would listen and say, ‘Okay.’ It would be so restful” — for Dern embodies it in the world-weary way she carries herself afterwards, as the full brunt of her client’s biased disregard for her opinion washes over her. Reichardt shows Dern driving, her eyes on the road ahead, her preoccupation with what has happened silently mingling with the need to make this turn, to mind that car, to take the next exit. And so, when we finally receive Meloy’s dialogue via a phone conversation, it feels like she is giving voice to thoughts we’ve already seen written on her face.

Later, when we’re introduced to Gina — played by Michelle Williams and based on a character from Meloy’s story “Native Sandstone” — Reichardt again gives preference to a moment of quiet meditation. Looking out of place dressed in chic athletic wear in the middle of the wintry Montana outdoors, Gina is walking back to the campsite where her daughter and husband pack up for the day. She is consumed by the landscape as she puffs on a cigarette, something clearly on her mind. As we learn later, she is intent on moving here and building a house that captures the spirit of the land around it. “Gina wants the house to be authentic,” her husband explains, to an old man whose sandstone they wish to buy — rumored as it is to have been reclaimed from the town’s old schoolhouse. Just as Meloy threads the story of a fraught marriage through her text without it taking over, Reichardt likewise relies on Williams to convey the narrative’s depth of feeling, which many other directors might have chosen to spell out.

In the film’s third and most striking section, adapted from Meloy’s short story “Travis, B.,” Reichardt goes a step further. The central character appears almost exclusively in near-silent scenes that ask us to inhabit her head, all but demanding we intuit for ourselves what she might be thinking. On the page “Travis, B.” follows Chet Moran, who grew up in Logan, Montana where a bout of polio left him with a limp, a physical reminder of his own inability to comfortably exist within his own body. While working at a ranch tending to horses he decides to venture into town one evening, where he stumbles onto a night class at the local high school, taught by a young lawyer. He’s taken with the lawyer, Beth, and clumsily invites her out to eat afterwards, despite the fact that she will need to drive back nine hours to where she lives. During their quick diner date, Meloy gives us access to both Chet and Beth’s inner monologues:

She studied him and seemed to wonder again if she should be afraid. But the room was bright and he tried to look harmless. He was harmless, he was pretty sure. Being with someone helped — he didn’t feel so wound up and restless.

The generous spirit of Meloy’s free indirect discourse is translated intact into Reichardt’s screen adaptation. With unfussy shots of her actors she offers us plenty of time to discern the way they measure each other’s company, before easing into a comforting routine that follows every class. While the dynamic at work is never precisely clear, the shared intimacy between them is palpable, in these late-night moments when Beth’s tiredness is buoyed by the other’s eager company. But the gendered dynamics that Meloy carefully deconstructs — Chet grows attached to Beth and proceeds to drive across state to see her one last time, a gesture as aggressive as it is romantic — are not only upended but altogether reframed in Reichardt’s retelling. Rather than a strapping, if timid, young man, Chet becomes a young woman: Lily Gladstone portrays the rancher who becomes smitten with her younger teacher, played by Kristen Stewart.

What fascinates about the gender switch is that Reichardt feels little compelled to change much (or anything, really) about the rest of the piece. After offering Beth a ride on one of the horses to the cafe where they’ve met before, the rancher awkwardly stands before her, shifting her weight from foot to foot. In Meloy’s telling this is the moment when Chet “wanted to kiss her but couldn’t see any clear path to that happening.” In Certain Women — and in ways that speak to the semiotic slippage, from certainty to ambiguity, which the title sets up — Gladstone’s rancher appears to ponder those very thoughts, her musings seemingly no different than if she were a man. In turning Meloy’s characters into women who tentatively crave and pursue a same-sex attraction, Reichardt has found a simple and efficient way to deepen the central tension of this coupling. In her hands, “Travis, B.” unearths the quietly radical proposition of a connection between two women that follows and exceeds the confines of the romantic template Meloy arranged in her story. Beth and the Rancher’s hesitant relationship is both simpler and more complicated than on the page, though Certain Women is content with letting audiences fill in those pauses themselves, inciting us to reflection in the face of a straightforward narrative of longing, followed by loss.

It’s the details that accumulate and remain once the credits roll, even if little has been resolved. A woman wiping her mouth with a napkin still wrapped around diner cutlery, another absentmindedly playing with a sandstone pebble, a man slurping a chocolate milkshake in prison. The images are fleeting but they speak to the unguarded moments Reichardt hones in and pauses on, bringing viewers closer to her characters even as they suggest a more expansive canvas. Reichardt, building on Meloy’s concise prose, finds depth in the elemental brushstroke, a life lived in the pregnant pause.