interviews

Like Riding A Wave: An Interview With Paul Lisicky, Author Of The Narrow Door

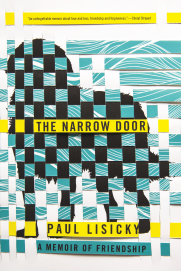

Paul Lisicky has long been one of my favorite essayists. His collection Famous Builder is one to which I return again and again, consistently in awe of his language, his insight, and the way he renders lived experience on the page. When reading Lisicky’s work, I feel as though gladly suspended in a spider’s web, the whole world put on pause. That is to say I feel held and fed by his work, and as much as I am and remain devoted to his previous books — the aforementioned Famous Builder, his terrific and tragically under-read novels Lawnboy and The Burning House, as well as his collection of short prose, Unbuilt Projects — Lisicky is at his very best in his latest book, The Narrow Door: A Memoir of Friendship (Graywolf, 2015), which traces, among many other things, his intimate friendship with the late writer Denise Gess and his separation from his long-time partner, M. The Narrow Door is a document of Lisicky’s attempt to understand. It isn’t written from a place of having already understood — supposing such a place is possible to arrive at when we’re talking about grief and loss, when we’re talking about ourselves at all — and this vulnerability makes all the difference. The book is smart, deeply moving, exquisitely written, and made of that open-eyed, open-hearted seeking that characterizes the very best of narrative nonfiction. “What is it like to know a single human in time?” the book asks, and moves us, as it moves its writer, toward something like an answer.

Lisicky and I spoke by email about the book, the complex dynamics of intimacy, natural disasters, the (in)adequacy of language, and more.

Vincent Scarpa: You have such a gift for juxtaposition. It’s staggering, the way you place three or four things alongside one another in an essay and never force the connections, allowing instead for their own quiet but definite ringing to take place on the page and within the reader. In the process of writing an essay like “Furious,” for example — wherein you write about Joni Mitchell, your friend Denise Gess (around whom much of the book orbits), what you call your “morning project” of gathering and reading stories about animals, and a rather creepy encounter in Hyannis with a man who follows you home — are you conscious of the ricocheting between these seemingly disparate parts, or does that reveal itself in the act of writing? Is this kind of placement organic, purposeful, or somewhere in between?

Paul Lisicky: Well, this just goes to show that I must think through images rather than through content! The truth is each of those sections in “Furious” is organized around some image, and I hope the book works as a conversation between images: one image is meant to talk to the next and so on. Something approximating a through-line starts to develop in the “Imitation Jane Bowles” chapter. But the book’s structure is more associative than narrative.

It needed flex — by which I mean the book needed to accommodate anything in order to feel like grief.

At an early point I realized that the material was not going to behave conventionally. Three pages into the manuscript, and it already felt disobedient and unruly, which interested me of course. It needed flex — by which I mean the book needed to accommodate anything in order to feel like grief. It was just going to be a big old mess if a reader couldn’t at least sense an emotional logic. Once I started developing patterns — patterns in images, in sound — it felt like the book could move anywhere it needed to. It started to feel a little like composing a longer work of music. It didn’t need to be trapped inside some causal straightjacket. So I’d like to think of its structure as organic, but I was certainly making choices to help that happen. Ideally, I always want to write into a place where I’m both in control of and being controlled by. It’s a little like surfing, riding a wave.

VS: There’s a lot of natural disaster in the book — earthquakes, superstorms, remembered volcanic eruptions, tsunamis. I suppose it is a question about juxtaposition, too, when I ask what was the hoped-for effect in having the reader metabolize your writing about these things alongside the more prominent threads — your relationship with Denise, your marriage with M, etc. — in the book? It seemed to suggest to me something about the lived experience and its micro and macro fragilities, but I suspected something deeper still beyond that.

PL: I like your word metabolize a lot. One of the things I wanted to do was to break down the false distinction between the world out there and the world of the domestic life. What if some of the relationship dramas in the book were also natural disasters of a sort? What if the natural disasters were relationship dramas? I wanted the non-human passages to be more than metaphoric, or serve as vehicles for feeling.

I think there’s also a progression in the book. Initially, the volcanoes are a spectacle, a source of fascination — they’re viewed from a safe distance, through YouTube videos. Then there’s the earthquake in Haiti, with the teenager who’s buried alive. It’s harder to feel distant from that. By the time we get to the Gulf oil spill, the damage hits even closer to home. There’s the possibility of the entire east coast shoreline being spoiled — birds, dolphins, turtles dying by the thousands. It was unbearable to me at the time; it’s still unbearable to think about how that damage is still playing out. So what does it mean to live in a world where our ongoingness is hardly a given? How does it trouble our relationships, muck up our loyalty and hope?

VS: One of the things I loved most about The Narrow Door was the way in which you sort of lay bare the nuanced, contradictory, and sometimes unflattering dynamics of friendship that we’d prefer to think of as organic, automatic — for to acknowledge that there is even a slightly performative, affective aspect to friendship may feel ugly, or may make the relationship seem somehow dishonest or uncherished. Yet it’s the opposite here. In your fearless, clear-eyed investigation of the complex relationship between you and Denise, I come to understand both of you individually and as a unit far more honestly and vividly. I think there’s something really brave about being unafraid to look under the hood of that relationship, so to speak, and I just wondered if you could talk a bit about the impetus to probe this friendship, and any hesitation or misfiring you may have experienced along the way. Were there sentences that, once written down, surprised you — with clarity, with disjunct?

…love isn’t ever a pure, untroubled, static state.

PL: As soon as I started writing, really just a month or two after Denise’s death, I was coming up against the built-in problem of idealization. How do you write about losing someone you adore without romanticizing them? I knew there was a received narrative out there — the story of the sick person ennobled by illness, the survivor made larger by grief — and I knew it was important to complicate that, which might have led me to put some of the darker stuff on the page. I can’t say some of that material — “The Fire in the Road” chapter, for instance — doesn’t make me feel queasy, but love — love isn’t ever a pure, untroubled, static state. Sometimes we love people because of their difficulty; it’s part of their charisma, their appeal. Who wants to be involved with a boring, unchallenging person anyway? I always say I can’t stand competition, but somehow I ended up in a long friendship in which that stuff was in the air, or under the hood, as you say.

Sentences that surprised me? Well, the one I keep coming back to is: “The closer we get to someone the more we must stand humbly before his [her] freedom.” But those aren’t even my words. I heard them spoken in a church, and they reached me at just the right time.

VS: I also love what you say about friendships of this variety: “See how we’ve been a little bit in love all this time, and not able to say it? But that’s the story of any friendship that lasts this long. All those hours on the phone, in restaurants, in classrooms, or at the dog park — you couldn’t do all that and not be in a little bit of love.” This is something that doesn’t get written about often; or, it does, but it always lands in the clichéd rom-com places you expect it to. What were you aiming to say about this kind of nonsexual yet fully romantic variety of intimacy, and why do you think it’s such unexplored territory?

Maybe we place undue pressure on sex, as if putting ourselves inside of each other is the only way one could possibly feel wired to another human

PL: Well, I think all sorts of intimate relationships happen between people who wouldn’t otherwise have sex because of their sexual identities. They happen between straight men, between gay men and straight women, they happen between old people and young — we could keep going. Those relationships might have all the intimacy of romance, but they’re untroubled by sex and the physical longing it generates. It’s not that there might not be eros in those relationships; it’s just that sexual expression isn’t front and center. Who knows why such relationships aren’t talked about in the culture? Maybe we place undue pressure on sex, as if putting ourselves inside of each other is the only way one could possibly feel wired to another human. I’m the last person to undervalue the pleasures of sex, but I have been close to many people in my life where sex wasn’t part of the equation. Not so long ago I read a really thoughtful essay by D. Gilson about what he calls “romantic friendships.” He writes about them through the lens of Frank O’Hara’s relationship with the painter Grace Hartigan, who was a straight woman and an artistic collaborator and/or muse. He believes that crossing that boundary, destabilizing the norm, is potentially “one of great queerness.”

VS: You write, “I see how a book becomes your house. But soon you are just a function of the house. The house tells you what you want, how you should live. At the same time, everything that comes into your life goes into the house. The house transforms the ordinary into the extraordinary, and without it, you’d never even know yourself, never even know that all those choices and consequences mattered.” I wonder if you aren’t saying something here about the information-gathering process, about the way the writer’s mind pivots toward meaning, or a bending toward resonance, when looking out at the world. Is that how it felt, writing The Narrow Door? That everything you took in could be made to fit into the repository of the text? I think many writers feel this way, and I think many writers, myself included, don’t really know when to stop looking at the world through the lens of our current project and see it as simply the world. Perhaps we never do?

PL: I think the distance involved in naming, sorting, in making structures — I can’t imagine that being anything but a good thing. This might sound extreme, but I know it’s saved my life more than once. I suppose it would be a mistake to be standing outside of your life all the time, never immersing yourself in it, or allowing yourself to be totally lost. But once you’ve developed the muscle I don’t think it’s exactly possible to stop. At this point I wouldn’t know how to live any other way.

VS: As one of my interests in my own nonfiction is the adequacy or inadequacy of language — specifically its ability to bear weight when writing about grief and loss — I was especially drawn to this passage: “Words fail in the face of strong emotion,” you write. “They hold too little; they don’t pour into one another the way I want them to. There are solid walls between each word, and even if I named every abstraction, the list would never tell the complete story. There would always be another word to follow the last word.” I found this beautiful, and true, and frustrating — and yet I was holding in my hands the finished book! This poet I like, Natalie Eilbert, has a line — “The agony of loss is its refusal/to be a vocabulary” — which also seems to speak to this. I guess what I’m asking, then, is how do you resign yourself to the inability to tell, as you say, “the complete story?” And, furthermore, what gets set free in the writer when he makes that resignation?

PL: Alongside that frustration of inadequacy, I have to think of each book as “a” truth instead of “the” truth. I wouldn’t know how to proceed otherwise if my assignment was to do the latter. By that I mean, each book is shaped by the time in which it was written, what was going on in my life when it was written, as well as by its own thematic currents. The Narrow Door is not the final word on Denise and it’s definitely not the final word about my long life with my ex. This material will probably find its way into other sources, and I’m sure I’ll find new things to say as I gather more into my experience. So I guess I’m saying it doesn’t quite feel like resignation if you hold on to the belief that there are always more books, more lives.