Books & Culture

LITERARY ARTIFACTS: The New Curiosity Shop

Just across from the New York Public Library’s brightly-lit gift shop is another kind of shop altogether: a windowless room full of dark-grained wood and locked glass cases containing priceless treasures. High up on the shelves are ships-in-bottles, stuffed blackbirds, model windmills, and tomes of mysterious origin. Silent patrons wander up and down the aisles, peering behind velvet curtains and opening tiny doors, revealing only they know what.

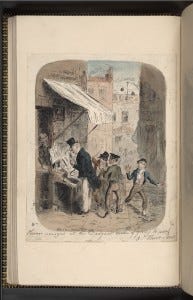

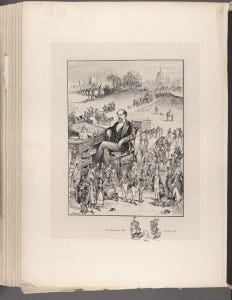

This modern-day cabinet of curiosities is the “Charles Dickens: The Key to Character” exhibit (now until January 27th) and the display cases are filled with defining images of Dickens’s beloved creations: there’s scrappy Oliver Twist, in an 1837 watercolor; there’s old Samuel Pickwick chasing his hat across a pencil drawing; little David Copperfield on a 1920’s dust jacket; decayed Miss Havisham in her wedding dress; and in a colored etching, with all his greatest expectations, Pip looks back over his shoulder as he leaves home.

To see them all in one place is to be astounded at the sheer number of indispensable characters Dickens dreamt-up, as well as their staying power in our literary imagination after more than 150 years. Ebenezer Scrooge alone has single-handedly inspired more than 22 films, 23 TV specials, 12 radio plays, and three operas. (The exhibit has an excellent black and white still of the late Gregory Hines as Scrooge, in the 1979 Broadway production of Comin’ Uptown.)

Quite a legacy. And dear old Scrooge is just one of 3,592 characters created by Dickens in his 34-year career in letters, from The Pickwick Papers right on down to the unfinished Mystery of Edwin Drood (now on Broadway!).

Looking at them all, one wonders: how exactly did he manage it? What insights did he have into the complexities of human character that let him render his own so unforgettably?

Especially because (as the many cartoonish illustrations in the collection suggest) Dickens’s characters are often rather two-dimensional. Poor orphaned Oliver Twist hasn’t a bad bone in his body and is unendingly sweet to everyone (even if he’s got to pick a pocket or two) while the barbaric Bill Sikes is never seen to do anything but spit, snarl, and wipe beer from his mouth with a handkerchief. Sikes beats his own bulldog until it needs stitches, murders his prostitute-girlfriend Nancy, and basically makes Breaking Bad’s Walter White look like a saint.

The exhibit’s curator, Professor William Moeck, agrees that many of Dickens’s memorable characters are “melodramatically polarized,” explaining that he was “influenced by the fairy tales and allegories [he] read in his youth […] villains are exaggeratedly wicked, while heroes and heroines wear almost saintly auras.”

But if this seems like a recipe for caricature and not character, then why are they so long-lived? Writer E.M. Forster struggled with this same question. While condemning flat characters in his Aspects of the Novel, he gave Dickens a pass. “Dickens’ characters are types,” he wrote, “but his vitality causes them to vibrate a little, so that they borrow his life and appear to live their own.”

Is it his vitality that really makes them resonate, or our own? If Dickens’s creations are flat perhaps they are elastic, like balloons, waiting for curious readers to come and inflate them. Like the heroes and monsters in our greatest myths, there is ample room inside them for us to live. Perhaps the secret to Dickens’s success was that he did not set out to create characters, but curiosities, which readers worldwide keep leaning closer to examine. We keep turning them over gently in our hands. Hence the 19th century Yiddish translation of Oliver Twist, just across from the 1914 David Copperfield, entirely in Chinese. Hence the stunning, runway-ready dress inspired by Miss Havisham, designed by Prabal Gurung and the sheet music for Debussy’s “Homage to S. Pickwick Esq. P.P.M.P.C.”

Yes, Dickens has had quite an afterlife, but he was also no Melville — unappreciated in his own day, beloved only later. No, Moeck notes, “Dickens was the best-loved English author at a time when recreational reading was at a zenith.”

One clear illustration of his appreciation in his own day is The Old Curiosity Shop, which inspired Moeck’s design for the exhibit. The novel was published between April 1840 and November 1841 in 88 weekly installments in the magazine Master Humphrey’s Clock. The curiosity shop is run by the cherubic Nell Trent (an orphan, naturally) and her kindly grandfather, but they soon fall prey to heartless Daniel Quilp, a loan shark who takes over the shop and evicts them. Eventually, “Little Nell” becomes homeless and ill, and though the love of her life attempts desperately to find her and set things right — spoiler alert — she ultimately dies in terrible poverty.

A bit melodramatic? Perhaps. Of the book, Oscar Wilde famously remarked, “One would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without dissolving into tears… of laughter.”

But the tale so captivated readers on both sides of the Atlantic that New Yorkers in 1841 were seen down at the docks, waiting to intercept incoming Brits who had already read installments which were still unpublished in America. Accosting anyone with a book in their hands, they begged to know, “Is Little Nell still alive??”

It’s enough to make you wish they still serialized novels.

Today the closest we come may be weekend television — with office kitchenettes abuzz each Monday, discussing the events of the previous night’s episode of Downton Abbey. Will Lady Mary Crawley finally get with Mr. Matthew Crawley? (Don’t worry. They’re third cousins, once-removed. It’s cool.) Will Lady Sybil run off with her dashing, anarchist chauffeur? What did the Dowager Countess say now?

In terms of books, perhaps the closest analogues we have now are the frenzies that surround the latest edition in a YA series. In 2007, newspapers and TV reporters were quick to recall the 1841 hubbub around Little Nell when they were describing the throngs of readers desperately waiting outside bookstores for the publication of the final Harry Potter book.

Will Harry defeat Voldemort? Will Bella choose Edward or Jacob? Will Katniss kill or be killed? Dickens knew that curiosity was the most powerful human motivator — more than violence or even sex, nothing excites us more than the simple question: What will happen next?

Curiosity can grow beyond the thirst for knowing, and become rather an anxiety to cease not-knowing. Years before Dickens, Samuel Johnson posited that “the gratification of curiosity rather frees us from uneasiness than confers pleasure; we are more pained by ignorance than delighted by instruction.”

In his 2006 essay “How to Read”, contemporary British writer Nick Hornby saw a valuable lesson in those who awaited anxiously for news of Little Nell. He argues that Dickens knew that “reading should be a joy” and wasn’t half as concerned with being smart as he was with entertaining his audience — pointing out that, “Dickens is literary now, of course, because the books are old.”

Of course there’s a lot more literary merit in Dickens than just being old. He’s hailed today as both a master of realism and of romanticism; he’s remarkable both as a journalist who investigated abject poverty and as a comic genius capable of leaving us in stitches. In an era before the cinema, using only language, Dickens zoomed through and panned across larger-than-life landscapes, inspiring the motions that the first generation of filmmakers would come to make with their cameras. Director Sergei Eisenstein credited Dickens’s parallel plots as the basis for his own groundbreaking montages, and those of D.W. Griffiths before him.

Today, at the NYPL exhibit, it is clear that the 3,593rd character that Charles Dickens created was Charles Dickens himself, and he is represented just like his other characters, by the daily objects he touched: his cat’s paw letter opener (previously seen at last year’s Finding the Future exhibit), the walking compass that he used to orient himself during his daily 25-mile walks, a set of fake books he had made with whimsical titles to trick houseguests, and his tattered reading copy of Oliver Twist, annotated over the course of many performances to show which parts to emphasize, and where to whisper. Supposedly he loved little more than standing in front of a crowd and rendering them spellbound with the tragic scene of Bill Sikes murdering the prostitute, Nancy.

If Dickens loved his audience, they more than returned the favor. Curious to meet the master storyteller, Dickens fans mobbed the author on his first tour in America. New York City threw an elaborate party called the “Boz Ball,” where 3,000 people came to celebrate Dickens’s arrival. Actors were paid to mime his characters in elaborate tableaux vivants, and sketches from the novels hung on the walls alongside portraits of American Presidents.

While those book parties may be dead, curiosity is not. When Haruki Murakami’s long-awaited 1Q84 was finally released in 2011, readers in New York found themselves in the grips of Murikami Madness. Arguably it was an appreciation for Jonathan Franzen’s talents that led someone to steal and ransom his glasses during the launch of his 2010 novel, Freedom (#franzen #glassesgate). When David Foster Wallace died, many of his readers mourned as if for a head of state. Whenever Jeffrey Eugenides writes his next novel, they’ll have to find a way of topping the gigantic billboard in Times Square that heralded The Marriage Plot. During the National Book Awards, my twitter feed ranneth-over with excited tweets from those at the party, thrilled to simply breathe the same air as Lorrie Moore. What is she working on these days? Is Philip Roth really retiring?

Dickens knew: readers are an unendingly curious bunch.

Today’s behavioral scientists agree that curiosity in human beings is not a basic animal instinct, but a full-fledged emotion which permits inquisitive thinking. More than a reflex; it is a desire, perhaps best described by writer Vladimir Nabokov who, a century later, began his lectures to Wellesley College students with this thought:

“If it were possible I would like to devote the fifty minutes of every class meeting to mute meditation, concentration, and admiration of Dickens. […] All we have to do when reading Bleak House is to relax and let our spines take over. Although we read with our minds, the seat of artistic delight is between the shoulder blades. That little shiver behind is quite certainly the highest form of emotion that humanity has attained.”

The “Key to Character” exhibit sets this quote beneath a scrap of paper from Nabokov’s notes, in which he has hastily diagrammed the novel. The three main themes are connected into a triangle by hard pencil lines. Hesitant bubbles surround the proper names of places and characters. Little arrows indicate how this thing leads to that. Words are crossed out and phrases are scribbled over, as one great master tries to glean the secrets of another, curiosity shivering from spine to page.

***

More Literary Artifacts here.

***

— Kristopher Jansma is a writer and teacher living in New York City. His debut novel, The Unchangeable Spots of Leopards, will be published by Viking Press in March 2013.