Books & Culture

Literary Secrets of Wimbledon

The legendary tennis tournament has its own verse inscription, its own library, and once, its own poet laureate

I inherited my love for tennis from my dad, who was at one time the number one player in Ireland. He raised his kids on the court; I have memories of trying to get away with hitting forehands double-handed because my racquet still felt heavy, since it was probably bigger than me. But my dad didn’t have to teach me to love the literature of tennis. I came to that on my own.

It was, however, a story from my dad that put me on track to the literary secrets of Wimbledon.

As a literature nerd and a tennis nerd, I’m not surprised that literature is woven through Wimbledon, the greatest tennis grand slam. The Championships live, after all, in the land of Shakespeare, an hour from the legendary Globe theater at the All England Lawn Tennis Club in southwest London. As much as Wimbledon is a temple to sport, it’s also a place that celebrates a subset of writing that doesn’t get enough attention on its own: tennis literature.

As a literature nerd and a tennis nerd, I’m not surprised that literature is woven through Wimbledon, the greatest tennis grand slam.

Tennis and writing have a long and harmonious history together. In fact, in my opinion,tennis literature deserves to be considered its own niche genre. When it is good, it is exquisite, because the game lends itself to narrative, demands creativity, offers endless fodder for analysis. And more than other sports, the subject translates from court to page because of the parallels between a tennis player and a writer: the strokes of a rally, the strokes of a pen; the lines on a court, the lines on a page; both must consider angles, anticipate response, and find something expansive and creative within the limitations of form. There are metaphors enough between the two figures that, to me, there is a kinship.

Tennis lit is primarily nonfiction: superlative sports journalism from the likes of Brian Phillips, Xan Brooks, and Louisa Thomas. But essayists, poets, and novelists have all explored their fascination with the game through their writing. In the contemporary era, highlights of that group include Claudia Rankine, Alvaro Enrique, John Jeremiah Sullivan, Martin Amis, Geoff Dyer, and, indelibly, David Foster Wallace. (His String Theory collection and more specifically the Michael Joyce piece are not only some of my favorite tennis essays but some of my favorite essays, period.) Journals dedicated to tennis have been around for almost as long as the lawn version of the game. Pastime launched in the 1880s, and the new publications that proliferate today are much more than stat and ranking roundups. The beautiful quarterly Racquet released its first issue in 2016 and showcases the likes of Ivy Pochoda, Sarah Nicole Prickett, and director Sam Mendes.

But the literary nature of Wimbledon isn’t a recent invention. As a reader, dad is a crime fiction guy, but he has a mysterious ability to pluck the odd poetry couplet from somewhere in the recesses of his mind and drop it into conversation, often changing the words to fashion an award-worthy Dad Joke. There’s this one line that he really likes, from Kipling’s “If — ”: “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster and treat those two impostors just the same…” Where he remembers this one from is not such a mystery. It’s inscribed above the players’ entrance to Centre Court at Wimbledon, and he spotted it there when he played the Championships as a junior in 1976.

The sign has become well-known, but it was my first indication that there was a literary presence around the All England lawns. Rudyard Kipling, the imperialist poet, christens the gateway to one of Britain’s most famous battlegrounds, one on which the empire’s soldiers have historically struggled. Such resilient pride, such proud resilience — how fantastically British, how typically literary! (Nota bene: This year, in the absence of the brooding Scot and world No. 7 Andy Murray, the UK’s hopes were with South African-born Kyle Edmund. On Centre Court, he fell to a Serb, Novak Djokovic, in the round of 32.) Kipling’s placarded words were presented to the club by one Lord Curzon, the last Victorian viceroy of India, in 1923. That first wooden inscription has been replaced twice due to refurbishments, but The Jungle Book author’s original lines still have an honorable, if rather hidden, place at the club: they arch the gallery in which the Rose Water dish and the trophy are displayed. I found them with the help of the most knowledgeable of guides: the Wimbledon librarian, Robert McNicol.

Wimbledon has the largest tennis library in the world. It’s located between the Draw board and the soon-to-be-roofed Court №1, but the entrance is subterranean. Housing more than 15,000 texts from about 90 different countries, the stacks are full of everything from Tennis Das Spiel Der Völker (“Tennis, the Game of the People”…questionable) by Burghard Von Reznicek, to Death on the Center Court by George Goodchild, which a reviewer panned in the New York Times in 1936 but which I still want to read, to Zimbabwean coaching instruction books.

A significant amount of shelf space, almost three walls worth, holds bound periodicals. This section contains complete sets of titles such as The American Cricketer, first published in Philadelphia in 1877; the original Il Tennis Italiano, which, as a visiting Italian writer told our librarian Robert, cannot even be found in Italy; the popular contemporary Tennis magazine; and items closer to the All England club such as the aforementioned British publication, Pastime. Eventually, Pastime became Lawn Tennis and Croquet, and later again, Lawn Tennis and Badminton. The magazine ceased publication after 1967, but its final year of circulation led to the very library in which its issues are housed: that year, they published an open letter from Alan Little who said that Wimbledon needed a library, found it outrageous that they did not have one already. About 10 years later, in 1976, when my father saw Kipling over Centre Court, the Kenneth Ritchie Wimbledon Library was opened by librarian Alan Little.

Robert was mentored by Little, who kept working in the library almost up to his death in 2017. Little was particularly proud of the periodicals collection. He felt this kind of writing captured tennis contemporaneously, with none of the fog of retrospection. Little’s service to preserving the story of tennis cannot be overstated. (He was knighted for it in 2014.) As a historian, Little was an assiduous collector of the hard facts of the sport. He launched the Wimbledon compendium, which now runs at 664 pages and contains every factoid and anecdote about every year of the Championships that you can and cannot fathom: the first woman to play without stockings (Ruth Tapscott of South Africa in 1927); the first year they had female line judges (1949); a list of “Champions who wore headgear in a singles final.” As a writer, however, Little had a taste for the more salacious and scandalous tales of the game. Of his own writing, his personal favorite was St. Leger Goold: A Tale of Two Courts. The book, one in a series of four, explores a true story about an Irish champion who, after his tennis success, moved to Monte Carlo in 1879 with his wife. They gambled, lost everything, and decided to murder a wealthy Danish woman to steal her riches. They packed her hacked-up body into a suitcase, got on a train to Marseille, and checked the luggage into a cloakroom to be forwarded to London. A porter got a whiff of the bag, though, and they were discovered. Goold died in a convict’s settlement in 1904. To me, this is a story deserving of the Netflix treatment.

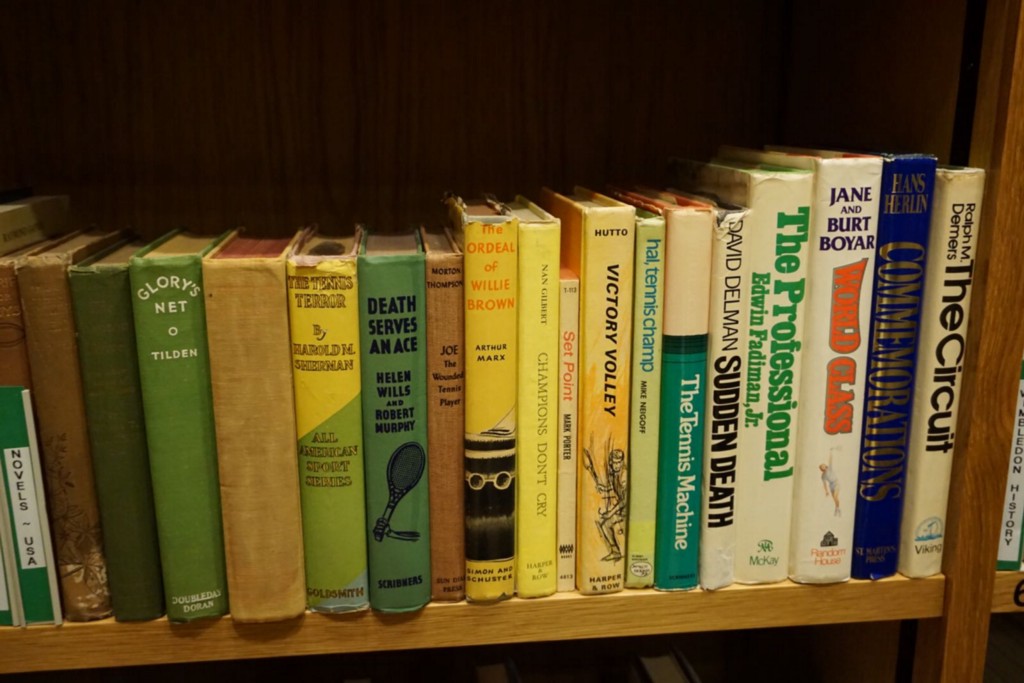

The library is primarily visited by writers doing research — not necessarily the literati that sprinkle the royal box. Books can be used but not taken from the premises, and an appointment is needed to visit. As Robert showed me around the collection, I realized the place was a visual representation of something that I have bemoaned alongside other tennis lit fans: the dearth of tennis lit in fiction. I was standing in the place where I was most likely to find all of it, and the novels take up just one stand of shelves. The spines, however, are enticing. A few players are represented; among them is Helen Wills, holder of 31 Grand Slam titles and apparently one fiction title, Death Serves an Ace. The under-celebrated Bill Tilden, who wrote 30 books and was the first American to win Wimbledon in 1920, appears with Glory’s Net, It’s All in the Game, and elsewhere. I picked up Nelson Hutto’s Victory Volley but the summary sounded a bit like a tennis version of Updike’s basketball-focused Rabbit books so I moved on. Sudden Death is on the shelf, but it’s a book by David Delman, not Alvaro Enrique’s recent (and excellent) novel with the same English-language title, about a not-necessarily-factual game of real tennis between the painter Caravaggio and the poet Francisco de Quevedo. Perusing led me to a few questions: what are the eligibility requirements for a place on the Wimbledon shelves, and how does acquisition happen? Is this a Library of Congress situation, if you write about tennis are you required (or would it at least behoove the work) to submit the book? Is there a hidden room of networked computers that beep and print a page of code whenever a book is published that uses the word “tennis”?

“The book has to be about tennis,” says Robert when I ask how they gain entry. This sounds intuitive but vague. Perhaps there are secrets that can’t be shared, because more nebulous still is the acquisition system. After years as the only person doing what he was doing, Alan Little has built quite a network of rare book collectors, fellow tennis enthusiasts, publishers, and writers. This web of people and relationships is the system of discovery that leads to acquisition — there’s no secret computer room. During my tour, two of Robert’s colleagues worked at a nearby table cutting newspaper clippings and pasting them into a large book of bound blank pages. I find it encouraging that an institution can modernize its infrastructure so thoroughly — the new, state-of-the-art roof for court 1 is hanging out like a giant, dead tarantula beside the Aorangi pavilion while it waits to be mounted — and still preserve its soul, the little human details. It’s like Pimms on tap: tradition meets modern demand.

When the Wimbledon tournament began in the 1870s, it more or less solidified the rules of the game as we know it, so there really isn’t a better place than Wimbledon for tennis’s literary history to be preserved. The Brits really do love a Bard — in 2010, Wimbledon partnered with the Poetry Foundation and that year’s Championships Artist was the first Official Wimbledon Poet. (Sample verse, about the interminable Isner-Mahut match that year: “High performance play / all day yet still no climax / it’s Tantric tennis.”) Unfortunately, he was also the only; the haikus have not continued.

13 Tennis Books That Weren’t Written by David Foster Wallace

Stories swirl through this place — matches that changed the game, player histories that make their success seem superhuman, smaller anecdotes like Ilie Nastase and Jimmy Connors’ heated backgammon games at the players lounge. On Saturday the female victor will hoist the beautiful Rose Water Dish, and on Sunday the man will receive a trophy that I learned this week is, in fact, meant to look like a pineapple. (Apparently, back in the day, pineapples were considered rare and glorious enough to be emblemized on a trophy. It is amazing to me that Wimbledon chose a fruit other than a strawberry for the ultimate pride of place.) I love how tennis is written, but on finals day on Centre Court, two players represent all of the heartbreak and triumph of the defeats and victories during the two-week tournament, years on the tour, lifetimes of dedication and sacrifice. And this, to me, is still the most thrilling tennis story of all.