Craft

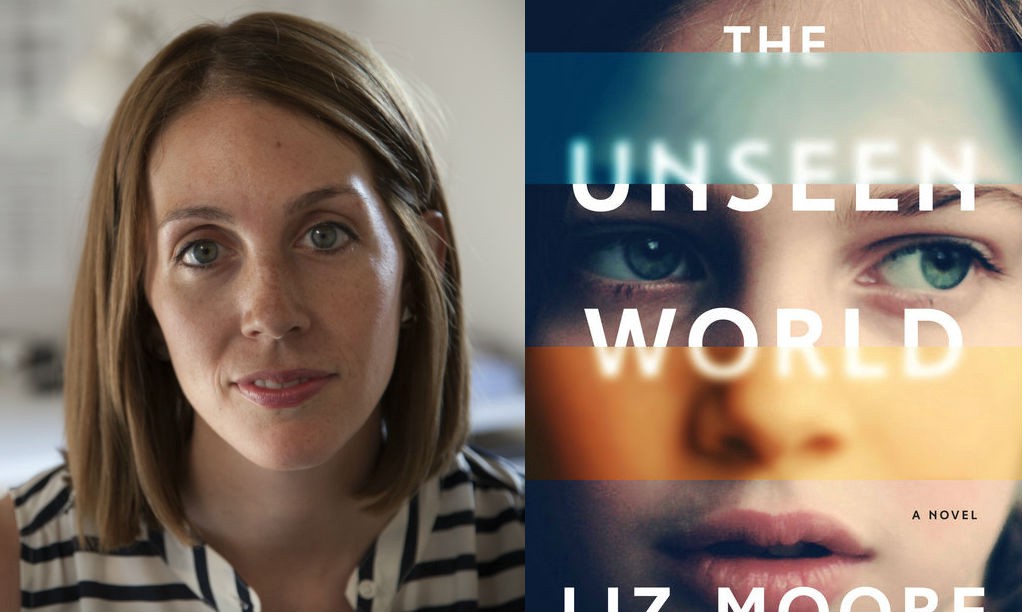

Liz Moore’s Family of the Future

The Author of The Unseen World Talks Chatbots, Catholic School and Father-Daughter Relationships

One of my great joys in life is a well-plotted literary novel. I’m talking about a book that’s shameless about its twists and turns, a book that loves a big reveal, a book with Secrets and Backstories and Subplots — and high-level language to match. I love Marilynne Robinson as much as the next girl, and I’m down for a Valeria Luiselli meta-novel any day, but there’s a special place in my heart for a literary writer who, when given the options of language, character, and plot, says, Yes, please.

Enter Liz Moore. I had to kick off our interview by telling her all the questions I wasn’t going to ask because I didn’t want to spoil the plot of her new novel, The Unseen World (WW Norton & Co, 2016). Lucky for me, that left us plenty to talk about: fathers and daughters, Catholic schools, memory loss, 1980s chatbots, writing about science when you’re not a scientist, and much more. I promise, we didn’t give anything away.

Lily Meyer: Did you always know who the narrator would be?

Liz Moore: No, I didn’t. I experimented a lot with point of view. In early drafts it was in the first person, in the voice of [twelve-year-old protagonist] Ada. I discovered that the book just felt better when I was writing in the third person.

Lily Meyer: So what’s your drafting process like? Are there a lot of false starts, or do you write all the way through?

Liz Moore: I never write all the way through. A lot of my early work on the book is incredibly problematic; I’m starting and stopping, not writing a complete story with an arc. There are a lot of failed attempts, and I piece them together one by one until I arrive at something that resembles a complete first draft, but I have hundreds of attempts before that. They aren’t wastes, because the character work goes into the first real draft, and because I need to figure out what doesn’t work many, many times before I figure out what does work.

Lily Meyer: What elements of those initial attempts have made it into The Unseen World?

Liz Moore: The characters of Ada and David, her father. I had a sense of them as people right from the beginning. Every other element of the book has changed dramatically. David was a physicist at first, not a computer scientist; Ada was older than she is in this draft, and I spent more time in her adulthood. But I always knew that they were a pair, and that it would be a novel about a father and daughter.

Lily Meyer: Where did you get that?

Liz Moore: My father is a physicist. I spent a lot of time around him, hearing him talk about his work, and around his colleagues, and sometimes at his lab, though nowhere near Ada’s daily routine of going with her father to his lab. I became intrigued by the idea of writing about the experience of a child who’s really gifted at science, because I wasn’t. I was much more interested in reading and writing, and so the book let me explore what it would have been like to be really strong in what my father was always strong in.

Lily Meyer: How much did you have to learn about computer science?

Liz Moore: A lot. I was interested in computers as a kid, but computers weren’t that interesting. Early personal computers were pretty basic. But I was still interested in spending time on them, and played around with early computer games like Space Quest. I chatted with ELIZA, which was an early chatbot program and which became the grain of inspiration for ELIXIR, the computer program that functions as another character in the book.

Lily Meyer: Tell me more about talking to ELIZA!

Liz Moore: My father needed computers at home for his work, so we always had them — Macs, always — which was relatively uncommon. On those computers, certain programs came pre-loaded, and ELIZA was one. Like ELIXIR, ELIZA was designed to act like a therapist. It searched keywords in what you said and then asked general questions, so if you said anything about your mother, ELIZA would say, “Tell me more about your family.”

I was kind of a loner as a kid, so there was something satisfying about talking to a computer program…

Even as a young kid, it was obvious to me that this was its mechanism, but I felt strangely compelled to talk to it. I wanted to talk to it. I was kind of a loner as a kid, so there was something satisfying about talking to a computer program that would ask me questions about myself. That experience inserted itself into the novel, where there’s a computer program that’s much more advanced. ELIXIR is a combination of ELIZA and a program called CYC, which is an ongoing self-teaching computer project.

Lily Meyer: Speaking of self-teaching, David home-schools Ada for a long time, but once he begins to lose his memory, she goes to Catholic school at Queen of Angels. How does Catholicism play into this book for you?

Liz Moore: I grew up in Framingham, outside Boston, and most of my friends grew up very culturally Catholic. The parochial-school element comes out of growing up in the Boston area and having so many friends and acquaintances who practiced Catholicism and who were part of what felt to me like very warm, very loving families. So when Ada moves in with David’s colleague Liston and goes to parochial school with Liston’s sons, that’s tied up in a sense of family for me, more than faith.

I should also note that I spoke with people who grew up in Savin Hill, the neighborhood in Dorchester where Ada lives, and that’s just where characters like Ada and the Liston boys would have gone to school. Everybody in Savin Hill went to Catholic school.

Lily Meyer: When you were doing research interviews for The Unseen World, how did you explain the book you were writing?

Liz Moore: I was very nervous every time I was speaking to someone who’s in computer science. I have multiple hang-ups about my own perceived lack of scientific ability, and have ever since I was a kid. Fortunately, I found people who were genuinely kind about it, and interested when I explained my goal in writing the book, which was not to be perfectly scientifically accurate but to construct a story that borrowed from reality but was also somewhat speculative and could move into places that don’t exist yet. I tried to tell them that I was willing to include inaccuracies for the sake of plot.

I almost always described the book as the story of a father and daughter who both work in computer science. The father’s mind begins to fail, and at the same time, it becomes clear that he’s been dishonest about his past. The daughter has to work for the rest of her life to figure out who he was and why he lied. That’s the very short summation I gave.

Lily Meyer: How do you explain the book to yourself?

Liz Moore: It’s about possibilities for what the future could look like, and it’s about family — and sort of about my family — and it’s about outsiders, and adolescence, and hero worship. I’m naming its themes, I guess.

Lily Meyer: Speaking of family, has your father read the book yet? What does he think?

Liz Moore: He read a first draft of it, and this past weekend he finished the final version. He likes it! He certainly had a lot of notes on the first draft about all the things I’d gotten wrong, the language I used for computers and labs, and that was really helpful. I was nervous that he would see himself too much in the character of the father, because in almost every way as people, they’re quite different. It was only the grain of having a scientist father that began the book for me.

Lily Meyer: When you’re writing and editing, who do you show your work to, and when?

Liz Moore: I’m extremely secretive. Usually I show my work to nobody at all until I have a complete draft. This is the first book that I sold based on a partial manuscript, so I did show it to my agent and editor, but I’ve never done that before. My editor purchased it, but then I didn’t show her any more till I had a complete draft. I don’t show friends or my husband anything until I feel like it’s as good as I can make it. If I know it’s not really good yet, I don’t feel like it would be helpful to show anyone. They’d be telling me things that I already know. I want to bang my head into a wall until I feel like it’s good and then have someone else tell me what’s not good about it.

Lily Meyer: What does banging your head against a wall look like for you?

Liz Moore: The only constant is disconnecting from all technology for a set number of hours and seeing what happens. That’s the only way I can ever have breakthroughs. If a book isn’t going well, that’s when it’s hardest to work on it, so I will sit in front of my computer with the Freedom program enabled and leave my phone behind and force myself to either write — I’ll open up a new document so that psychologically I’m not committing too much to the draft — or just think. I sit and stare at the blank screen and try to work through a problem.

I hate that part. A lot of times I feel like I’m doomed and it’s not going to work, like I’ve written myself into too much of the corner and there’s no way out, or I started with a faulty premise and it’s just not going to work. That thought is almost always there. And then eventually something just clicks. It usually involves a huge amount of work on what I’ve already written, but I know that that’s the answer and the work will be productive.

Lily Meyer: How do you protect yourself from that feeling that you’ve written yourself into a corner?

Liz Moore: At this point the only comfort that I have is that it happens with every book. Now that I’ve written three books, on number four, I can say to myself, “This is part of the process.” With The Unseen World, I could remember, “Okay, you felt just as bad with the first two books.” That’s the way I can convince myself to keep going.

Lily Meyer: How do you protect the brain space you need for writing from all of the rest of life?

Liz Moore: It’s incredibly important to me to read. If I don’t read, I have a hard time writing. So I need to assign myself reading time the same way I assign myself writing time. I have a very full teaching schedule — I’m an associate professor at Holy Family — which is a job that I love, but a job that requires a lot of work. And I just had a baby in late May, so for the first time this fall not only am I going to balancing teaching and writing, but I’ll be balancing teaching, writing, and parenthood. I don’t know what it’ll be like. It’s going to be a huge change.