interviews

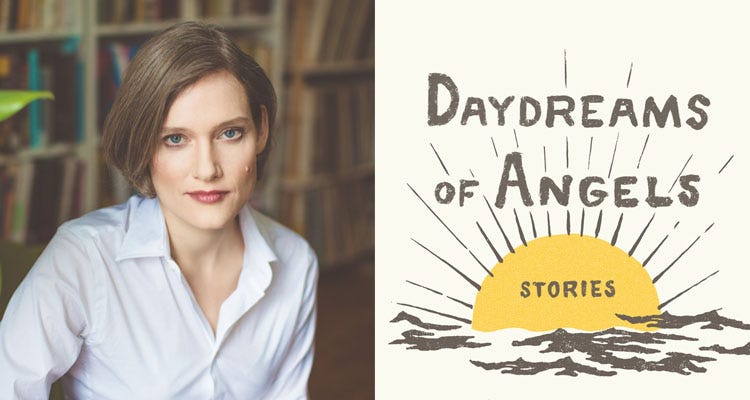

Looking for the Artistic Moment: An Interview with Heather O’Neill

by Melissa Ragsdale

“Swan Lake for Beginners” by Heather O’Neill is featured this week in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading with an introduction from Diane Cooke. O’Neill’s new collection, Daydreams of Angels, is available in the US October 6th, 2015 from Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux.

Melissa Ragsdale: “Swan Lake for Beginners” and the many different Nureyev experiments ask the question, what creates an artist? With every variable the scientists manipulate, each generation of clones’ relationship to dance changes, and though they can recreate Nureyev’s body and mind, the scientists are ultimately unable to recreate his talent and passion. This evokes a debate that pertains to all artistic pursuits (including writing): the debate over whether success is the result of innate talent, or a result of hard work. And there’s another question there, about the role inspiration has to play in creating art. In your own experience, how do these apply to your life as a writer? How do you value them, on a more abstract level?

HO: This is a question that I’ve grappled with. I think that there is obviously a thing called talent. But that isn’t the only thing that makes an artist. There’s an illusion that art is easy.

There’s a sort of mad devotion that’s involved in becoming an artist. Artists make great sacrifices to do what they do. You can’t teach someone to be obsessive and passionate and consumed by their art. This is an absurd desire that has to come from within the artist.

It’s an act of resistance. You have to want to create something new. I think there’s something wild about that decision to live your life outside the box. It’s wonderful. That’s why we like artists’ biographies. It’s lovely to trace that original spark. We like to examine the artist as child — singing on a street corner in Paris, stuck in a workhouse, sitting in the back of a Chevrolet — and figure out when and where this child formed the determination to be great.

It’s always a mystery. The scientists in my story are looking for that moment and trying to recreate it.

MR: A follow up question, if it applies: do you see this story as having any kind of lesson or moral?

HO: It’s that there is a possibility that an artist may come from anywhere. I’ve always loved artists that appear out of nowhere, from unexpected circumstances, without anyone prompting them or encouraging them to take that path in life. We need artists coming from all sorts of backgrounds and classes — that’s how we understand the breadth of the human condition and all walks of life. So if there’s a moral, it’s that we have to look for and support and encourage artists who are coming out of odd backgrounds.

MR: Why did you choose Rudolf Nureyev as the vehicle of this story?

HO: I grew up in the 1980s. We all walked around as though we were ballet dancers, wearing leg warmers and our sweaters over one shoulder. I begged my dad to sign me up for jazz ballet classes above the grocery store. I’ve always adored the ballet. “The Dance of The Four Little Swans” in Swan Lake was a huge influence of me as a writer. I wanted to write in a way that was precise, repetitive, naïve, youthful, practically naked.

Nureyev was my favorite dancer of all. I was always obsessed with Nureyev. I remember him being on The Muppet Show as a kid. He was such a superstar then. And he always seemed cheeky and disdainful and arrogant. As a child you are always getting scolded for being openly miserable. Here was a man who was allowed to be dour and pissed off even though he was invited to be on such prestigious shows as The Muppet Show.

I loved his temperament. So part of the idea of choosing Nureyev as the figure to be cloned was that it was really funny to imagine a town that was filled with Nureyevs, all complaining about things and being vain and contrary and beautiful.

And then I chose him because he had the most wonderful and difficult biography. He was somebody who grew up under enormous hardship and had to struggle to be able to dance to be free. So it would be difficult for the scientists to discover how to recreate this tortured drive.

MR: Project Siberia takes place in such a curious setting: a French-Canadian town posing as a Siberian Russian town during the Cold War. What drew you to this particular cultural intersection?

HO: That was in part for humorous effect too. The landscape of Northern Quebec is a lot like that of Siberia. I liked the idea of the experiment being in my home province.

Each of the stories has a Montreal aspect or link. It’s a running theme. It’s because I spent my childhood in Montreal. And I think that every child — well, in a way every reader — when they are reading a text, supplies their own set of references. The meaning of any text will change given where it is read and according to the specific cultural references and beliefs or the reader. The attempt to find meaning in life is always going to be filtered by the cultural biases that we are seeing them through. So it was to make my authorship and the context and time that I was retelling these tales explicit.

I also liked the idea of a little kid from a working class Quebecois background finally reaching glory through the very refined art of ballet. Sort of mirrors the original Nureyev’s ascendance. And my own, really.

MR: In Daydreams of Angels, you use concoctions of fun/bizarre details to pull on real and serious threads of investigation. How do you balance the peculiar with the realistic?

HO: You don’t want everything to be randomly quirky and absurd. It’s more interesting if there is something real about the setting and the situations and the characters. And then the peculiar elements act as a sort of metaphor to highlight an existential question or conundrum that one of the characters is grappling with. Each story has to adhere to some magical laws. The worlds in the book applies the Laws of Physics of a seven-year-old girl. It was a world in which things that children believe to be real are actually real. Their dolls actually do get heart sick with grief when they are left alone.

***

Heather O’Neill’s first novel, Lullabies for Little Criminals, earned accolades around the world, including being named winner of Canada Reads 2007 and the Hugh MacLennan Prize for Fiction, and being a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for Fiction and the Orange Prize. Her second novel The Girl Who Was Saturday Night was a finalist for the 2014 Scotiabank Giller Prize. She is a regular contributor to CBC Books, CBC Radio, National Public Radio, The New York Times Magazine, The Gazette (Montreal) and The Walrus. She was born in Montreal, where she currently lives.