interviews

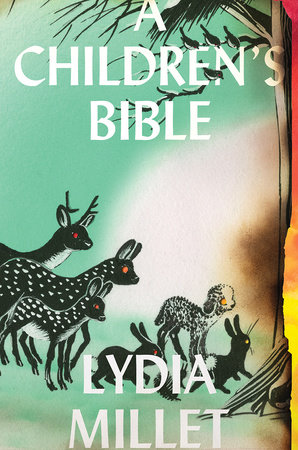

In Lydia Millet’s “A Children’s Bible,” the Kids Save the Parents from Apocalypse

Millet's novel is an American chaos story about a climate-changed future

Lydia Millet has always fought for the environment. She has written many books that take the natural world as their subject, but her signature approach is refreshingly askew, shot through with humor and satire. She gives animals perspective in her collection Love in Infant Monkeys, explores ecotourism and marine conservation through mystical creatures in Mermaids in Paradise, and extinction and evolution via taxidermy in Magnificence. That list is a mere sampling; she’s written sixteen books, including two short story collections and four young adult novels. As if that weren’t enough, she also spends her days working as a senior editor for the Center for Biological Diversity in Tucson, Arizona, a non-profit with the mission to use “science, law and creative media” to “secure a future for all species, great and small.”

A Children’s Bible, her sixteenth book, tells the story of Eve and her companions, who range in age from young children to graduating teenagers. Their parents, friends since college, have rented a grand summer house for a protracted and debauched reunion. Eve, our narrator, speaks mostly in the first person plural, giving an account from a collective perspective. “Once we lived in a summer country,” the novel begins. “In the woods there were treehouses, and on the lake there were boats.” In this summer country, the only apparent act of parental supervision has been to lock the children’s phones in a safe. Their summer is idyllic, until it isn’t. A major storm that floods the property is just the start. Technologically incapacitated, the children move outside, where they become like the Lost Boys—self-governed and free, until the lack of adult leadership forces them to be the grown-ups.

A Children’s Bible is a thrilling novel of climate change: motivating but not didactic; electrifying, when so many of us are at our most inert. Like all of Millet’s work, A Children’s Bible gains strength from its contradictions. It is hilarious yet tender, absurd yet chillingly realistic, nostalgic yet prescient.

Halimah Marcus: The first time I read A Children’s Bible, I felt upset to no longer be a child. The young people in this story are so much more appealing than the adults. They’re not corrupted by a lifetime of responsibility and mistakes. They’re smarter, they’re savvier, they’re more loving and more kind. Did you have to battle any of your own vanity or defensiveness as an adult in order to malign the adults as a group?

Lydia Millet: I think there’s something wishful about the way that I portray the young characters in this book. Of course, in real life there are some compensations for agedness, including certain forms of wisdom and wit and sometimes vision that we don’t always have when we’re younger. We lose other things like memory and motor skills, and quickness, alacrity, reflexes, and also our experience of the world as a novelty. That’s what I most miss from being a teenager, how everything sometimes seemed enchanted and mystical.

I actually think that teenagers have as many blind spots as anyone else, just maybe different blind spots. On the matter of climate, the urgency of that crisis, and the urgency of the extinction crisis, I happen to think the generation that I’m writing about (and those say, in their twenties and maybe thirties), are more right than the generations older than them. The righteous anger that the [the younger generations] command is long overdue. I wanted to write them having a general wisdom that represented that more specific wisdom that I believe they really do have.

Not all adults are repulsive and selfish and hedonistic, and I certainly hope and kids can be equally all of those things, especially teenagers. When you’re a teenager you get to suspend empathy for a while, neurologically and otherwise. But you also have access to all these forms of rapture that I think we grow out of. I wanted to look at the more ecstatic and rapturous time of life.

HM: This particular exchange in the book hit me where I live, as they say. The parents acknowledge that they’ve let the children down by not protecting the planet. A mom asks, “But what could we have done really?” The children respond:

“Fight,” said Rafe.

“Did you ever fight or did you just do exactly what you wanted?” said Jen. “Always.’”

I was like, shit, that’s me. I convince myself that I’m doing something by taking public transportation, recycling, not using plastic bags, but I don’t make any real sacrifices. How do you reconcile compassion for your characters and the people you love in the real world with the condemnation that we all deserve for our complacency with climate change?

LM: First of all, I think that there’s plenty of blame to go around. There is personal blame that we can absorb, but really so much of this was directly caused by much more powerful actors than we are. Climate change was very directly funded and caused by the fossil fuel industry, who we now know had pretty much mastered the science of climate change back in the 70s and certainly by the 80s. They had a vast storehouse of information and actively suppressed it. We should look first to the powerful to hold responsible for this thing.

Not everyone can have a job that has to do with the things that mass social and cultural transformation. We have to have normal jobs. So how do we tackle these huge, future-oriented abstractions? It’s a tactic that has been used by climate deniers and by vested interests in big industry: just tell people they should recycle and guilt them about their own lifestyles, when really it’s macro social things that determine our lifestyles. It’s laws, it’s policies. Many of us can’t do anything about those on the individual level. So it’s a tactic of deflection from people who actually can do something on a policy level to blame regular people for their wasteful habits, and just turn everything on the victim. It’s victim blaming, basically.

That’s not to say that we can’t all live more responsible lives, but I’m someone who believes really strongly that the structural change on the scale that’s needed to tackle extinction and climate change absolutely has to come from the law and from policy. It has to come from the top. To put it on the bottom, on those of us who are just regular people, to put that pressure on us is disingenuous. It needs to come from our representatives. It needs to come from Congress. It needs to be policy that people have to live by. That’s the only way we can change the habits that we have that have gotten us into this mess. I firmly place the blame on the powerful and not on you.

HM: Well, thank you. I appreciate that!

You called climate change a huge future abstraction. How do you find narrative purchase in something like that, that’s a slow moving, global phenomenon? Is the American perception of climate change particularly resistant to narrativizing it?

I believe that the structural change on the scale that’s needed to tackle extinction and climate change absolutely has to come from the law and from policy.

LM: Those are really good questions. I’m not sure I have all the answers. It is difficult. It is difficult to make stories that aren’t dull or polemic out of these things that are so big. The only thing we can do is—other than write nonfiction, of course, and pass laws and do reporting—but in terms of fiction, all we can do is tell stories in voices that we like about characters that we like, or don’t like, or like to not like, or whatever. It’s always been difficult for me to write about these catastrophic historical events in fiction for the same reason that it’s difficult for anyone to write about them in fiction, which is that there’s a grandiosity to them. It’s like writing about God. The grandiosity is difficult to approach as a peasant, and that’s what one always is with these large things.

And there are so many landmines when you approach the majesty of some of these immense subjects that are fraught with political judgments. There’s the risk of writing too much like an activist. I think it’s great to be an activist. I don’t want to write like an activist. It’s a balancing act. I don’t think any of us ever feel we completely succeed when we try.

HM: In addition to the 100 year storms that become more frequent in the novel, there’s a nasty bug that gets passed around between the parents. In most disaster/apocalypse stories—novels, movies, whatever it is—there’s one event that threatens civilization. It’s an asteroid. It’s a tidal wave. It’s a contagion. But in A Children’s Bible, the threats are recursive and multi-valenced. How did you choose the disastrous events in the novel, and how does that thinking apply to our current situation? I’m particularly curious about connections you see between the pandemic and climate change, which on the surface may not seem immediately related.

LM: I think they’re really closely related, as you might imagine. Both climate change and the pandemic are the direct result of the way that we’re abusing the natural world. The actual novel coronavirus probably came to us from bats via pangolins, maybe via civet cats, and then via wildlife markets. We know that the disease itself is most likely the result of the exploitation and abuses of the wildlife trade, international in this case. But we do a lot of it here at home as well.

Huge numbers of animals are taken from the wild for trafficking, turtles especially. Freshwater turtles in the US are taken by the millions. Climate change and extinction, which are so interconnected you can’t really decouple them anymore, are driven by this exact same abuse of the natural world, rampant plundering of it that’s gone on for a few centuries now. They have essentially the same root cause. Of course, the economic effects and the scope of the pandemic here in the US are a political product, not an environmental product. This thing didn’t have to end up this way.

Chaos looks like everything and also like nothing. Some of us, at least, are experiencing the pandemic almost as a form of stasis, or limbo, or powerlessness. All the kids across the country having to be homeschooled and being bored out of their mind, including my two. And at the same time, for many, for those in extremist, it’s desperate and life threatening. But there are these different circles of experience. In any chaos scenario, some people are insulated from the worst effects and others are on the front lines and exposed.

HM: There are groups of people who believe that in order to be prepared for a disaster, having a gun is top of the list. The idea is outsiders will come for your supplies. You need to be able to defend your homestead. And but then there are examples of people coming together as communities rather than turning to violence against their neighbors. In New York City we have the examples of 9/11, the blackouts, hurricane Sandy.

There’s also these new prepper communities like The Prepared, which I read about in the New York Times, that are trying to appeal to “common sense” preppers that are less libertarian and even liberal. Without giving anything away, in A Children’s Bible, there’s someone who turns out to be a top level prepper. That person has guns and it becomes necessary to use those guns. So where do you fall on this spectrum? Are guns necessary for survival? Would you have a gun in your bunker?

Both climate change and the pandemic are the direct result of the way that we’re abusing the natural world.

LM: I’m not a gun owner and I choose not to have a gun in my bunker. First of all, your likelihood of actually dying in an untoward, untimely way is so much higher if you have an actual gun in your house. On that basis alone, I’ve never wished to [have one]. Also they scare me and they’re creepy and when I hold them, I feel wrong.

I’ve lived basically out in the desert for more than 20 years now. Here, the geography, the distance between people, actually emboldens people around guns, as well as making them feel more isolated and perhaps defensive to begin with. It makes complete sense to me that dense urban communities would not be as gun wielding. It’s almost not as real that people are getting hurt by these things when you’re all spread out and you don’t see another person for four miles.

I do believe in other forms of prepping, just not the guns. I’m not handy enough to be a prepper. My boyfriend is pretty handy and he can do a little prepping, but I lack the skills required. I can just basically order stuff on the internet and I can prune some plants in my yard. One of the more alarming things about the prospect of a near apocalypse is the handiness that would be required to cope. I am just not a self-sustaining organism, really.

HM: In terms of the decision to include violence and guns in the novel, I’m inferring from your earlier answer that it has something to do with the intertwining of all of these threats. Is that right?

LM: I think that America is a place where sooner rather than later in any kind of situation of mass instability, there will be guns and they will be brandished in public. The pandemic has actually already shown us a glimpse of this, with people showing up with guns at state capitals and stuff like that. I didn’t think I could really write an American chaos story without some guns showing up.

Gun stories aren’t particularly interesting in and of themselves. It’s just, are those characters who are holding the guns interesting, or not?

HM: I don’t want our readers to think that you’re exclusively concerned with doom and gloom because you’re one of the few writers that consistently makes me laugh out loud.

I didn’t think I could really write an American chaos story without some guns showing up.

LM: Thank you. It is my chief goal, actually. It’s actually my chief goal. I laugh out loud when I’m writing. That’s what I really love to do. I’m not saying it happens all the time, but I really do enjoy it.

HM: You’re almost exactly anticipating my question, which is, how is your humor on the page different or similar to your humor in your daily life? How do you decide which jokes make it through to the final edit? Because I’m sure you can’t laugh every time you work on the book.

LM: When I write something that tickles me, it is diminishing returns of laughter. The first time, you’re like HA! Whatever, I can’t do a fake laugh. And then the second time, you’re like… [chuckles]. And then by the fifth time you read it, you’re like mm-hmm.

But the test there is actually more like, does it displease me? Does it actually displease me, actively? You come to see that something’s too clever over time, and over successive reads.

HM: Shifting gears, to a career question: You’re a very successful novelist. You’ve published 16 books, you’ve been long-listed for the Pulitzer ( for Love in Infant Monkeys) and the National Book Award (for Sweet Lamb of Heaven), won many fellowships and awards, but you still keep a full-time job. Can you tell me about your work at the Center for Biological Diversity? How does it inform your writing? How do your ambitions and aspirations apply to your two different, and both impressive, careers?

LM: My work is technically full time, but I do keep it to more like 30 hours per week, plus some evenings, so I have a little time left over to do my own things. I do the job because it feels useful and practical. My position is not fancy, even though I’ve been there on and off for more than 20 years.

I keep my work there really modest and really detail-oriented. I do a lot of proofreading and copy editing. It does require quick turnarounds during the day for press releases and action alerts that have to go out soon. We do a huge volume of those things. And so it’s busy, but I don’t manage anyone else. I’m no one’s boss.

The beautiful thing about it is that it allows me to do things that I believe in without having to actually march along the street, holding a sign or chaining myself to a bulldozer or anything like that. I don’t prefer those things. I’ve always felt really sheepish and embarrassed in activist or protest situations. It’s just not really a natural fit for me. I don’t really like sloganeering, but I really do believe in the things that we do at work. I’m really inspired by the people I work with, who are mostly scientists and lawyers. I just want to do something useful. I’ve always felt the writing I do is just pure self-indulgence. It’s just pure happiness. There’s nothing about it that isn’t selfish to me. I do exactly what I want [when I write]. I just also need to do stuff that’s practical and it’s also nice to have a salary and health insurance. I love my work at the center, but I’m no conservation superstar or anything. I’m just a worker bee.