Lit Mags

Mariachi

by Juan Villoro, recommended by George Braziller Press

AN INTRODUCTION BY LEXI FREIMAN

What I admire most about Juan Villoro’s fiction is the way he uses character to deepen our understanding of cultural symbols and reveal their shared inconsistencies, to complicate them. “Mariachi” is a great example. The story investigates masculinity and authenticity, using the beloved “national prejudice” that is the mariachi. And, as with all of Juan’s stories, every aspect of the narrative — plot, setting, character — is rich with cultural representations engaged in dialectical struggle. Which sounds dry. But isn’t, because Juan is really funny. Funny and skilled in bathos — as the systematic humiliation of his characters, the assault on their expectations. The mariachi, Julián, has both a private jet and crippling phallic insecurity. Julián swims in the deep end with porn actors, European auteurs, and stadium-packing mariachi superstars; his celebrity milieu grants the reader access to the super-ego of a nation.

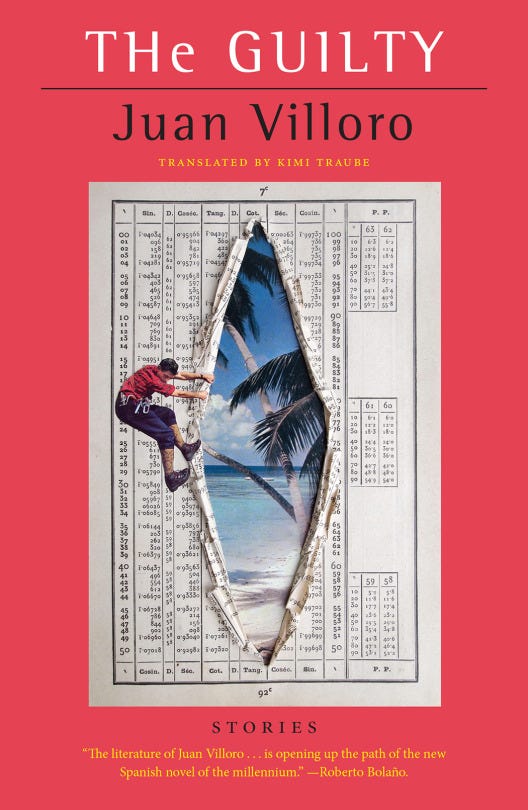

All through The Guilty — his first collection to be translated into English — Juan mobilizes stereotypes of contemporary Mexican and North American culture. We encounter border truckers, soccer stars, and gluten-free, liberal media journalists. Juan has a keen eye for the absurd, the hypocritical, and is unafraid to let his characters be culpable. That said, the stories never stray far from the myopic, the banal, the moments that make his larger-than-life characters familiar and potentially pardonable. A masterful satirist, Juan knows that the greatest moments of cultural insight occur at the points of greatest confusion. When Julián’s girlfriend insults former Formula One World Champion, Michael Schumacher, he muses: “There are moments like that. A man can accelerate up to 350 kilometers an hour, he can win and win and win, he can donate a fortune, and he can still be treated this way, in my own bed.”

Lexi Freiman

Editor, The Guilty

Mariachi

Juan Villoro

Share article

by Juan Villoro, recommended by George Braziller

“Should we do it?” asked Brenda.

I looked at her white hair, split into two silky blocks. I love young women with white hair. Brenda is 43 but her hair has been this way since she was 20. She likes to blame it on her first shoot. She was in the desert in Sonora, working as a production assistant, and she had to round up 400 tarantulas for some horror-movie genius. She pulled it off, but when she woke up the next morning she had white hair. I suppose it’s genetic. Anyway, she likes to see herself as a heroine of professionalism who went gray because of tarantulas.

Strangely, albino women don’t excite me. I don’t want to explain my reasons because when they’re made public I realize they aren’t really reasons. I had enough of that with the horse thing. Nobody has ever seen me ride one. I am the only mariachi star who has never in his life mounted a horse. It took the reporters nineteen video clips to catch on. When they asked me about it, I answered, “I don’t like transportation that shits.” Very banal and very stupid. They published a photo of my platinum BMW and my 4×4 with the zebra-skin seats. The Society for the Protection of Animals said they were ashamed of me. Plus, a reporter who hates me got his hands on a photo of me holding a high-powered rifle in Nairobi. I didn’t hunt any lions because I didn’t actually hit any, but there I was, all dressed up for safari. They accused me of being anti-Mexican for killing animals in Africa.

I made the horse declaration after singing until three a.m. in a rodeo arena at the San Marcos Festival. I was leaving for Irapuato two hours later. Do you know what it feels like to be fucked up and have to leave for Irapuato before the sun rises? I wanted to sink into a Jacuzzi, to stop being a mariachi. That’s what I should have said: “I hate being a mariachi, singing under a five-pound hat, tearing myself to pieces, swollen with the resentment earned on ranches without electricity.” Instead, I said something about horses.

They call me El Gallito de Jojutla, the Little Rooster from Jojutla, because that’s where my father’s from. They call me little rooster but I’m not an early riser. The trip to Irapuato was killing me — one of the many things that were killing me.

“Do you think I’m too sexy to have been a neurophysiologist?” Catalina asked me one night. I said yes to avoid an argument. She has the mind of a porno screenwriter: she likes to imagine herself as a neurophysiologist, stirring up desires in the operating room. I didn’t tell her that, but we made love with extra passion, as if to satisfy three curious onlookers. Afterwards I asked her to dye her hair white.

Since I met her, Cata’s hair has been blue, pink, and cherry red. “Don’t be a jackass,” she answered. “There are no white dyes.” That’s when I understood why I like young women with white hair. They’re not on the market. I told Cata this and she went back to talking like a porno screenwriter: “What’s really going on here is that you want to fuck your mom.”

Those words helped me a lot. They helped me leave my therapist. He thought the same thing as Cata. I had gone to see him because I was sick of being a mariachi.

Before lying down on the couch, I’d made the mistake of looking at his chair: on the seat was an inflatable donut. Maybe it comforts some patients to know their doctor has hemorrhoids; someone intimate with suffering to help them confess their own horrors. But not me. I only stayed in therapy because my therapist was a fan. He knew all of my songs (the songs I sing: I haven’t written any), and he thought it extremely interesting that I was there, with my famous voice, saying I’m fucking fed up with ranchera music.

Around the same time, an article appeared where they compared me to a bullfighter who’d gone through psychoanalysis to overcome his fear of the ring. They described his most terrible goring: his intestines fell out onto the sand in the Plaza Mexico. He picked them up and managed to run to the infirmary. That afternoon, he had been wearing dark purple and gold. Psychoanalysis helped him get back in the ring with that same suit on.

My doctor flattered me so ridiculously, I loved it. I could fill Azteca Stadium — including the field — and get 130,000 souls to drool. The doctor drooled and I didn’t even have to sing.

My mother died when I was two years old. This is an essential piece of information for understanding why I can cry on cue. All I have to do is think about a photo. I’m dressed in a sailor suit, she’s hugging me and smiling at the man who would drive the Buick that flipped over. My father had drunk more than half a bottle of tequila at the rancho where they’d gone to eat lunch. I don’t remember the funeral, but they say he threw himself weeping into the grave. He got me into ranchera songs. He also gave me the photo that makes me cry. My mother smiles, in love with the man who’s taking her to a party. Outside the frame, my father snaps the shot with the bliss of the wretched.

It’s obvious I want my mother back, but I also like women with white hair. I made the mistake of telling my therapist about the theory Cata got from the magazine Contenido: “You are Oedipal. That’s why you don’t like albino women, that’s why you want a mommy with gray hair.” The doctor asked me for more details about Cata. If there’s one thing I can’t fight her on, it’s her notion that she’s extremely sexy. This titillated the doctor and he stopped singing my praises. I went to our last session dressed as a mariachi because I was coming from a concert in Los Angeles. He asked to keep my tricolor bow tie. Does it make sense to talk about your inner life with a fan?

Catalina was also in therapy. This helped her to “internalize her sexiness.” According to her, she could have been many things (almost all of them terrifying) because of her body. On the other hand, she believes the only thing I could have been is a mariachi. I have the voice, a face like an abandoned ranchero, and the eyes of a brave man who knows how to cry. Plus, I’m from here. Once I dreamed the reporters asked me, “Are you Mexican?” “Yes, but next time I won’t be.” This response, which in real life would have destroyed me, drove them wild in my dream.

My father made me record my first album at 16. I never went back to school or looked for another job. I was too successful for a career in industrial design.

I met Catalina the way I met my previous girlfriends: she told my agent she was available. Leo said Cata had blue hair and I figured she could probably dye it white. We started going out. I tried to convince her to bleach it, but she didn’t want to. Plus, authentic white-haired women are inimitable.

The truth is I’ve found very few young women with white hair. I saw one in Paris, in a VIP lounge at the airport, but I froze up like an idiot. Then there was Rosa, who was 28 with beautiful white hair and a diamond-encrusted belly button which I only knew about because of the swimsuits she modeled. I fell for her so hard it didn’t matter that she said “jillo” instead of “Jell-O.” She didn’t pay any attention to me. She hated ranchera music and wanted a blond boyfriend.

That’s when I met Brenda. She was born in Guadalajara but lived in Spain. She went there to get away from mariachis. Now she was back in Mexico with a vengeance. Chus Ferrer, a genius filmmaker I knew nothing about, was in love with me and wanted me in his next movie, no matter the cost. Brenda had come to round me up.

She got chummy with Catalina and discovered they hated the same directors who had ruined their lives — Brenda’s as a producer and Cata’s as an eternally aspiring character actress.

“Brenda has a nice figure for her age, don’t you think?” Cata said. “I’ll take a look,” I answered.

I had already looked. Catalina thought Brenda was past it. “A nice figure” was her way of applauding an old nun for being thin.

I only like movies with spaceships and children who lose their parents. I didn’t want to meet a gay genius who was in love with a mariachi who was, unfortunately, me. I read the screenplay so that Catalina would get off my fucking back. The truth is they only gave me bits and pieces, just the scenes in which I appeared. “Woody Allen does the same thing,” Cata explained to me. “The actors only figure out what the movie is about when they see it in the theater. It’s like life: you only see your own scenes and the big picture escapes you.” That idea seemed so accurate I thought Brenda must have told it to her.

I suppose Catalina was hoping they would give her a role. “How are your scenes?” she said every three seconds. I read them at the worst possible time. My flight to El Salvador was cancelled because there was a hurricane, and I had to go by private jet. Amid the turbulence of Central America, the role seemed incredibly easy to me. My character answered everything with “Heavy, man!” and let himself be adored by a gang of Catalonian bikers.

“What do you think about the scene with the kiss?” Catalina asked me. I didn’t remember it. She explained that I was going to “tongue kiss” a “really filthy biker.” She thought the idea was fantastic: “You’re going to be the first mariachi without complexes, a symbol of the new Mexican.” “The new Mexican kisses bikers?” I asked. Cata’s eyes lit up: “Aren’t you tired of being so typical? Chus’s movie is going to catapult you to another audience. If you keep doing what you’re doing, soon you’ll only be interesting in Central America.”

I didn’t respond because at that moment a Formula 1 race was starting and I wanted to see Schumacher. Schumacher’s life isn’t like a Woody Allen script: he knows where the finish line is. When I was moved that Schumacher had donated a huge sum to the victims of the tsunami, Cata said: “Do you know why he’s giving so much? He’s ashamed of having gone there for sex tourism.” There are moments like that. A man can accelerate up to 350 kilometers an hour, he can win and win and win, he can donate a fortune, and he can still be treated this way, in my own bed. I looked at the riding crop I go out on stage with (it’s good for whacking away the flowers they throw at me). Then I made the mistake of picking up the crop and saying, “I forbid you to say that about my idol!” In one instant, Cata saw both my gay and my sadomasochistic potential: “So you have an idol now?” She smiled longingly, as if waiting for the first lash. “Fuck, yes,” I said, and went down to the kitchen to make myself a sandwich.

That night I dreamed I was driving a Ferrari, running over sombreros until they were nice and flat, nice and flat.

My life was unraveling. My worst album, a series of ranchera songs composed by Alejandro Ramón, the hit maker from Sinaloa, had just gone platinum, and my concerts with the National Symphony at Bellas Artes had sold out. My face stretched out over four square meters on a billboard in the Alameda in Mexico City. I didn’t care about any of it. I’m a star. Forgive me for saying it again. I don’t want to complain, but I’ve never made a decision in my life. My father took charge of killing my mother, crying a lot, and making me into a mariachi. Everything else was automatic. Women seek me out through my agent. I fly a private jet when the commercial liners can’t take off. Turbulence. That’s what I depend on. What would I like? To float in the stratosphere, look down at Earth and see a blue bubble without a single sombrero.

I was thinking about that when Brenda called from Barcelona. I pictured her hair while she said, “Chus is flipping out over you. He put a hold on the house he’s buying in Lanzarote while he waits for your answer. He wants you to grow your fingernails out like a vamp. Perfect for a slightly seedy queer. Do you mind being a vamp mariachi? You’d look just adorable. I fancy you, too. I suppose Cata’s already told you.” It excited me immensely that someone from Guadalajara could talk like that. I masturbated after I hung up, without even opening the copy of Lord magazine I keep in the bathroom. Later, when I was watching cartoons, I thought about the last part of our conversation. “I suppose Cata’s already told you.” What should she have told me? And why hadn’t she?

Minutes later, Cata showed up to emphasize how great I’d be as a mariachi without prejudices (contradiction in terms: mariachis are a national prejudice). I didn’t want to talk about that. I asked her what she’d discussed with Brenda.

“Everything. It’s incredible how young she seems for her age. Nobody would ever think she’s 43.”

“What does she say about me?”

“I don’t think you want to know.”

“I don’t care.”

“She’s been trying to convince Chus not to hire you. She thinks you’re too naïve for a sophisticated role. She says that Chus has a chubby for you and she’s been asking him not to think with his dick.”

“That’s what she’s saying?”

“That’s how the Spaniards talk!”

“Brenda is from Guadalajara!”

“She’s been in Spain for decades, she defines herself as a fugitive from mariachis. Maybe that’s why she doesn’t like you.”

I paused, then told her what had happened:

“Brenda called a little while ago. She said she’s crazy about me.”

Cata responded like a stony angel:

“I’m telling you she’s super professional. She’ll do anything for Chus.”

I wanted to fight because I had just masturbated and didn’t feel like making love. But I couldn’t figure out how to offend her while she was unbuttoning her blouse. When she pulled off my pants, I thought about Schumacher, the master of mileage. That didn’t excite me, I swear on my dead mother, but it filled me with willpower. We banged for three hours, not quite as long as a Formula 1 race. (Thanks to Brenda, I had started using the Spanish: “to bang.”)

I finished off my concert at Bellas Artes with “Se me olvidó otra vez.” When I got to the line, “in the same city with the same people,” I saw the journalist who hates me in the front row. Every year on my birthday, he publishes an article “proving” my homosexuality. His main argument is that I’ve made it to another birthday without getting married. A mariachi should breed like a stud bull. I thought about the biker I was supposed to tongue kiss. I looked at the journalist and felt assured he would be the only one to write that I’m a fag. Everyone else would talk about how virile it is to kiss another man just because the script calls for it.

The shoot was a nightmare. Chus Ferrer told me Fassbinder had made his star actress lick the floor of the set. He wasn’t that much of a tyrant: he settled for smearing me with garbage to “muffle my ego.” I had it easier than the lighting crew: he kept screaming “neo-fascist plebs!” at them. Whenever he could, he grabbed my ass.

I had to wait for so long on set that I became a Nintendo prodigy. I was also growing more and more attracted to Brenda. One night we went out to dinner on a terrace. Luckily, Catalina smoked some hash and fell asleep on her plate. Brenda told me she had had a “very tumultuous” life. Now she led a solitary existence; it was necessary to satisfy Chus Ferrer’s production whims.

“You’re the latest.” She looked me in the eyes: “It took me so much work to convince you!”

“I’m not an actor, Brenda.” I paused. “I don’t want to be a mariachi, either,” I added.

“What do you want?”

She smiled in an alluring way. I liked that she hadn’t said: “What do you want to be?” It seemed to suggest: “What do you want now?” Brenda was smoking a small cigar. I looked at her white hair, sighed as only a mariachi who has filled stadiums can sigh, and said nothing.

One afternoon a porn star visited the set. “His penis is insured for a million euros,” Catalina told me. Brenda was standing beside me. She said, “The long shot million,” and explained that this had been the slogan for Mexico’s national lottery in the 70s. “You remember things from such a long time ago,” Cata said. Even though the phrase was offensive, they went off happily to get dinner with the porn star. I stayed behind for the tongue kiss scene.

The actor who was playing the Catalonian biker was shorter than me and they had to put him on a stool. He had taken ginseng pills for the scene. Seeing as I had already conquered my prejudices, I thought it sounded like a faggy thing to do.

I was paid the same amount for four weeks of shooting as I got for one concert in any remote ranch in Mexico.

On the flight back they gave us tomato salad and Cata told me about a trick of the trade she’d heard from the porn star. He ate lots of tomatoes because it improved the taste of his semen. The female porn stars appreciated it. I was intrigued. Did that kind of courtesy really exist in porn? I ate the tomatoes off of my plate and hers, but when we got back to Mexico she said she was dead tired and didn’t want to blow me.

The movie was called Mariachi Baby Blues. They invited me to the Madrid premier, and as I was walking the red carpet I saw a guy with his hands outstretched like he was measuring a yard. In Mexico that gesture would have been obscene. It was obscene in Spain too, but I only realized that after I saw the movie. There was a scene where the biker came close to touching my penis and a colossal member appeared onscreen, impressively erect. I thought that was why the porn star had visited the set. Brenda schooled me: “It’s a prosthetic. Does it bother you that the public thinks it’s yours?”

What does someone who has become an overnight genital phenomenon do? At the after-party, the queen of pink journalism gushed, “It’s so shamelessly raunchy!” Brenda told me about celebrities who had been surprised on nude beaches and revealed penises like fire hoses. “But those penises are theirs!” I protested. She looked at me as if she was imagining the size of mine and seemed disappointed, but she was terribly nice and said nothing. I wanted to caress her hair, to cry into the crook of her neck. But then Catalina arrived, with glasses of champagne. I left the party early and walked through the streets of Madrid until the sun came up.

The sky had begun to yellow when I passed by the Parque del Retiro. A man was holding five very long leashes attached to five huskies. He had cuts on his face and he was wearing cheap clothes. I would have given anything to have no obligations except walking rich people’s dogs. The huskies’ blue eyes seemed mournful, as if the dogs wished I’d take them away with me and knew I couldn’t.

I arrived at the Hotel Palace so tired I was barely surprised that Cata wasn’t in the suite.

The next day, all of Madrid was talking about my raunchy shamelessness. I thought about killing myself but it seemed wrong to do it in Spain. I would mount a horse for the first time and blow my brains out in the Mexican countryside.

When I landed in Mexico City with still no word from Catalina, I discovered that the country adored me in a very strange way. Leo handed me a press folder full of praise for my foray into independent film. The words “manliness” and “virility” were repeated as often as “film in its pure state” and “total filmmaking.” My take was that Mariachi Baby Blues was about a story inside a story inside a story, where at the end everybody was very content doing what they hadn’t wanted to do at the beginning. A great achievement, according to the critics.

My next concert — in the Auditorio Nacional, no less — was tremendous. Everyone in the audience had a penis-shaped balloon. I had become the stallion of the fatherland. They started to call me the Gallito Inglés, the Cocky Little Rooster; one of my fan clubs changed its name to Club de Gallinas, The Hen Club.

Catalina had predicted the movie would make me a cult star. I tried finding her to remind her of that, but she was still in Spain. I got offers from everywhere to show up naked. My agent tripled his salary and invited me to see his new house, a mansion in the Pedregal neighborhood — twice as big as my own. A priest was there. He held a mass to bless the house and Leo thanked God for putting me at his side. Then he asked me to go with him to the garden. He told me the actress Vanessa Obregón wanted to meet me.

Leo’s ambition knows no limits. It was in his own best interest for me to date the bombshell of banda music. But I could no longer be with a woman without disappointing her or having to explain the absurd situation the movie had created.

I gave thousands of interviews but no one believed I wasn’t proud of my penis. I was declared Sexiest Latino by a magazine in Los Angeles, Sexiest Bisexual by a magazine in Amsterdam, and Most Unexpected Sexpot by a magazine in New York. But I couldn’t take my pants off without feeling diminished.

Finally Catalina came back from Spain to humiliate me with her new life: she had become the porn star’s girlfriend. She told me this in a restaurant where I demonstrated the poor taste of ordering a tomato salad. I thought about the porn king’s diet, but I barely had time to distract myself with that irritation because Cata was asking me for a fortune in palimony. I gave it to her so that she wouldn’t talk about my penis.

I went to see Leo at two in the morning. He took me to the room he calls his “study” just because there is an encyclopedia in there. He ran his bare feet back and forth over a puma skin rug while I talked. He was wearing a robe with dragons on it, like an actor playing a lurid spy. I told him about Cata’s extortion.

“Think of it as an investment,” he told me.

That calmed me down a little, but I felt drained. When I got home, I couldn’t masturbate. A plumber had made off with my copy of Lord magazine and I didn’t even miss it.

Leo kept pulling strings. The limo that arrived to take me to the MTV Latino gala had first picked up a spectacular mulatta who was smiling in the back seat. Leo had hired her to accompany me to the ceremony and increase my sexual legend. I liked talking to her — she knew all about the guerrillas in El Salvador — but I didn’t try anything because she was looking at me with measuring-tape eyes.

I went back to therapy. I explained that Catalina was happy because of an actual big dick and I was unhappy because of an imaginary one. Could life be that basic? The doctor said this happened to 90 percent of his patients. I quit therapy because I didn’t want to be such a cliché.

My fame is too strong a drug. I need what I hate. I toured everywhere, threw sombreros into grandstands, got down on my knees and sang “El hijo desobediente.” I recorded an album with a hip-hop group. One afternoon, in the main square of Oaxaca, I sat down on a pigskin chair and listened to marimba music for a long while. I drank two glasses of mezcal, nobody recognized me, and I believed that I was happy. I looked at the blue sky and the white line left by a plane. I thought about Brenda and dialed her on my cell.

“It took you long enough,” was the first thing she said. Why hadn’t I looked for her sooner? With her, I didn’t have to pretend. I asked her to come see me. “I have a life, Julián,” she said in an exasperated voice. But she pronounced

my name like it was a word I had never heard before. She wasn’t going to drop anything for me. I canceled my Bajío tour.

I spent three terrifying days in Barcelona without being able to see her. Brenda was “tied up” in a shoot. We finally saw each other, in a restaurant that seemed to be designed for Japanese denizens of the future.

“You want to know if I know you?” she said, and I thought she was quoting a ranchera song. I laughed, just to react, and then she looked me in the eyes. She told me she knew the date of my mother’s death, the name of my ex-therapist, my desire to be in orbit. She had admired me since a time she called “immemorial.” It had all started when she saw me sweat on Telemundo. It took her an incredible amount of work to get together with me. She had convinced Chus to hire me, wrote my parts into the screenplay, introduced Cata to the porn star, planned the scene with the artificial penis to shake up my whole life. “I know who you are, and my hair is white,” she smiled. “Maybe you think I’m manipulative. I’m a producer, which is almost the same thing: I produced our meeting.”

I looked her in the eyes, red from sleepless nights on film shoots. I acted like a stupid mariachi and said, “I’m a stupid mariachi.” “I know.” Brenda caressed my hand.

Then she told me why she wanted me. Her story was horrible. She explained why she hated Guadalajara, mariachis, tequila, tradition, custom. I promised not to tell anyone. I can only say that she lived to escape that story, until she understood that escaping it was the only story she had. I was her return ticket.

I thought we would sleep together that night but she still had one more production:

“I don’t mean to tell you how to do your job, but you have to clear up the penis thing.”

“The penis thing isn’t my job: you all invented it!”

“Exactly, we invented it. A European cinematic trick. I had forgotten what a penis can do in Mexico. I don’t want to go out with a man stuck onto a penis.”

“I’m not stuck onto a penis, mine’s sort of little,” I said.

“How little?”

Brenda was interested.

“Normal little. See for yourself.”

But she wanted me to understand her moral principles.

“Your fans have to see it,” she answered. “Be brave enough to be normal.”

“I’m not normal: I’m the Gallito de Jojutla, even pharmacies sell my albums!”

“You have to do it. I’m sick of this phallocentric world.”

“But are you going to want my penis?”

“Your normal sort of little sort of penis?”

Brenda dropped her hand to my crotch, but she didn’t touch me.

“What do you want me to do?” I asked.

She had a plan. She always has a plan. I would appear in another movie, a ferocious criticism of the celebrity world, and I would do a full frontal. My audience would have a stark, authentic version of me. When I asked who would direct the movie, I got another surprise. “Me,” answered Brenda. “The film is called Guadalajara.”

She didn’t give me the whole screenplay, either. The scenes I appeared in were weird, but that didn’t mean anything. The kind of films I think are weird win prizes. One afternoon, during a break in shooting, I went into her trailer and asked, “What do you think will happen to me after Guadalajara?” “Do you really care?” she responded.

Brenda had tried harder than anybody else to be with me. Had I embraced her in that moment I would have burst into tears. I was afraid of seeming weak when I touched her but I was more afraid that she might never want to touch me. I had learned one thing from Cata, at least: there are parts of the body that can’t be platonic.

“Are you going to sleep with me?” I asked her.

“We have one scene left,” she said, caressing her own hair.

She cleared the set to film me naked. Everyone else left in a bad mood because the caterers had just arrived with the food. Brenda put me next to a table surrounded by an enticing scent of cold cuts.

She stood in front of me for a moment. She looked at me in a way I’ll never forget, as if we were about to cross a river. She smiled, and said what we were both waiting for:

“Should we do it?”

She got behind the camera.

On the buffet table, there was a plate of salad. I was a foot away from it.

Life is chaos but it has its signals: before I took off my pants, I ate a tomato.