interviews

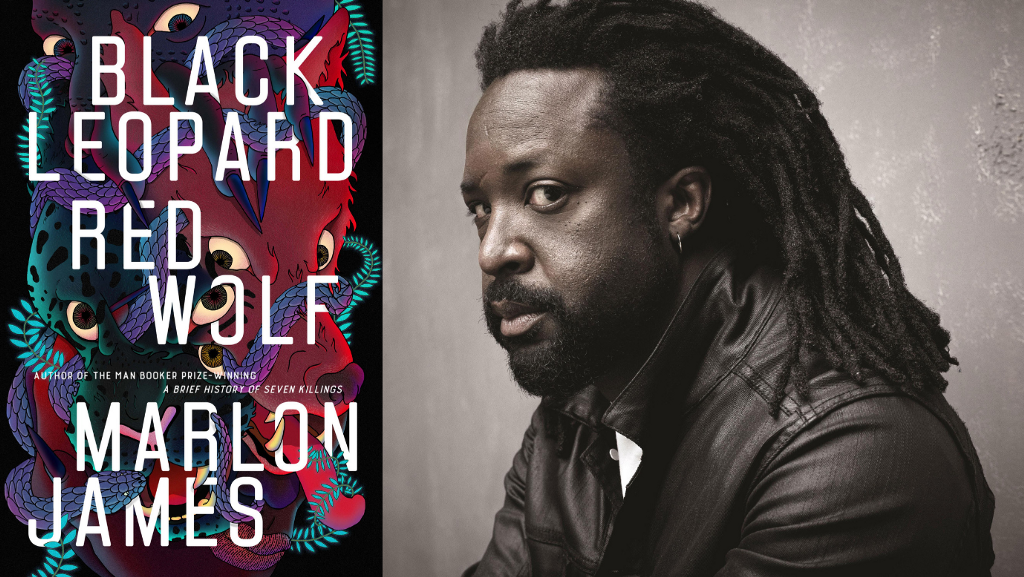

Marlon James Reclaims African Myths in Fantasy Saga “Black Leopard, Red Wolf”

Tochi Onyebuchi talks to the author about the first book in “The Dark Star Trilogy”

It’s tempting to say that Marlon James’s brand is violence: operatic, almost mystical, always exacting. It’s also tempting to say his brand is sprawl. Even the Jamaican novelist’s shortest book — John Crow’s Devil, at 206 pages — manages to turn a turf war between two local ministers into cosmic combat. It’s tempting, then, to say that the Marlon James brand is a uniquely postcolonial mélange of the terrestrial and the empyrean. Human frailty, human violence, human hope, all of these things are lent, in his work, a cosmogonal weight. Nowhere is this more evident than in his latest outing, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, the opening salvo in a mind-bending fantasy trilogy about a band of misfits hired to find and retrieve a mysterious young boy.

The fantasy takes place in Iron Age Africa seen through a mirror darkly. Phantasm is the order of the day; or, rather, the night. The dramatis personae includes a necromancer, a shape-shifting leopard who is sometimes animal and sometimes man, bush fairies, a girl made entirely of smoke, a giant who hates being called a giant, a very smart buffalo, trolls from the Blood Swamp, a vampire lightning bird and, well, the list goes on. A boy named Tracker is the book’s protagonist, gifted (or cursed) with the ability to find anything and anyone by simply inhaling their scent. As part of this group of mercenaries, he provides a window into a world at once hallucinatory and terrifyingly real.

James and I spoke over coffee and tea (as he had been nursing a cold) at Oslo Coffee Roasters in Brooklyn. We had first met at the Brooklyn Book Festival some years prior, I as a fanboy and he as a pre-Booker winner, and had the pleasure of appearing on a panel together at New York Comic Con a few years after, as colleagues and contemporaries. Our conversation ranged from the centrality of oral storytelling in non-Western cultures to Ninja Scroll, from Toni Morrison to narcocorridos, and, near the heart of it, to the obligations one had to navigate as a storyteller in the spotlight.

Tochi Onyebuchi: So, what did your editor say when you handed in the first draft of this?

Marlon James: He thought it was great! This is the thing: I was surprised at how open people are, because I expected a fight. And I expected a fight every step of the way. God bless Wakanda. Black Panther is a gift that keeps on giving. I remember, the same editor said to me, “you know, my sales team is so excited about this book.” I was like, “what did you tell them?” They said, “oh, I just mentioned Black Panther every five minutes.” So, to my pleasant surprise, they were super excited. And even when they were excited about the Africanness and the blackness, I thought they would stumble on the queerness. And they didn’t! Probably because it’s Riverhead; now I’m not trying to blow up Riverhead more than they need to be blown up, but they do behave quite like an indie publisher. They got people to read Brief History, shit! So, yeah, they were super excited about it.

TO: I think anybody familiar with your work — particularly Brief History — will notice the operatic violence and the really aggressive queerness. So, there’s not really any surprise there.

MJ: Which is why this doesn’t feel like a leap for me. For all sorts of reasons. One, it’s no secret how much I love scifi, fantasy and crime — so-called genre fiction. I’ve never been shy about that. That’s the stuff I grew up with. But if you’re gonna write with the Caribbean and the African — and you’re gonna subtract the Western worldview — then the stuff that they keep calling “magical realism” is real. And, even with all of that, I had to do some serious mental housecleaning. Because even when people write about mythology and witchcraft and so on, they still write from this Judeo-Christian point of view. That it’s not really real.

If you’re gonna write with the Caribbean and the African, then the stuff that they keep calling ‘magical realism’ is real.

TO: Sort of Orientalist.

MJ: Right. “It’s not gonna be real; it’s never gonna prevail.” And I was like, “oh, this is some serious shit. A hex is a hex.” Magic is real. These creatures are real. Ninki-Nanka was real until white preachers told them it wasn’t. It’s what you wanna accept as truth. People who believe in a magic baby born in a stable got no place attacking dragons.

TO: There’s a lot there that I want to unpack. But one of the things that really struck me about Black Leopard, Red Wolf was precisely that lack of a gulf between reality and dream, or, I guess, what we would call dream. Going back to the African epics, it’s all part of the world. It made me think of how different societies view mental illness. In the West, it seems very much a biochemical thing that emerges from a person, influenced by the environment. Whereas, in a lot of African cultures, particularly where my mom came from in Nigeria, it’s very much an externality. Demon possession. Or it’s a part of the world that’s dueling with the person.

MJ: But even that is pretty new. Because if you go to places that are way more connected to pre-Christian and Muslim Africa, like Uganda, schizophrenia “sufferers” (and I put that in quotes) have voices, but the voices are all affirmative.

TO: Like cheerleaders.

MJ: And they can be annoying. A bunch of people saying “you won; yes, you won; honey, you won” can be annoying too. The dilemma is: if you have your own personal cheerleading squad, why would you want to be cured? If you hear a voice, it’s the ancestors. In a lot of Hindu culture, if you hear a voice, it’s one of the millions of gods. Spirits. Judeo-Christianity comes in and says a voice is a demon. Science comes in and says the voice is a condition. So even the whole idea that they’re demons is still new. Scientists were baffled. “How do we treat this?” I don’t wanna lose my own damn cheerleading squad.

TO: In Black Leopard, Red Wolf, there’s a mystery that needs to be solved, there are crime elements but also epic fantasy elements — not necessarily a quest narrative, but there is the journey. And the motley crew that’s put together. Could you talk a little bit about how those influences came to bear, particularly on this work?

MJ: There are some obvious influences like Tolkien. The funny thing is, writing a book that is totally pulling from African mythology and history and religion and so on, but still being influenced by people like Tolkien and people even like Robert E. Howard, who wasn’t very keen on black people. To put it mildly.

TO: That’s very diplomatic.

MJ: Well, I stopped reading H.P. Lovecraft, because you gotta draw the line somewhere. But the quest narrative is not just Lord of the Rings. It’s Journey to the West. It’s the oldest plot in the book: people go on a journey. And you might learn something. At the same time, I wanted to poke holes in it. At one point, Sogolon goes “well, how goes your fellowship now?” Which might seem like a dig at Lord of the Rings — it’s really not. But it is a dig at this sort of “we’ll band together in a unified purpose, all for one and one for all.” No, humans aren’t like that.

TO: Nobody in this book is like that.

MJ: This fellowship breaks up from the moment they set out! Only one person in the entire group has a sense of mission about where they’re going and it’s Sogolon. Everybody else is either for the money or along for the ride. I was very interested in, knowing all of that, what would make people work together anyway. Or what would make people band together. What could sustain a narrative if it’s not everybody going for this magic child thing? And part of that too is remembering that when you’re writing the quest narrative, the destination is the least important thing. To come back to Europeans, that’s why The Odyssey was very helpful. I went back to all of it: The Odyssey, The Iliad. It’s how the actual journey profoundly changes you that, to me, was a more important story than what they’re on the road for. They lose sight of that or they get disillusioned by that. Or they’re plotting against each other. Or some people are more sold on the idea than others. And then, of course, people start betraying people. People start being human.

In the quest narrative, the destination is the least important thing.

TO: Even the shapeshifters.

MJ: Even the shapeshifters. Even the giant (who doesn’t want to be called a giant). Most journeys are anticlimax. Deliberately. Whatever you’re gonna learn about humanity through this land of monsters and creatures and mermaids and demons and so on — I actually think these might be the most humane characters I’ve ever written. And they’re all shapeshifters.

TO: Or people with no limbs who have to roll around everywhere.

MJ: I love that kid.

TO: With regards to the horrific creatures that you’ve injected into this narrative, it seemed to me very reminiscent of Dhalgren by Samuel Delany where you never really know how next the world is going to betray you. It’s like everything is out to kill you. This was the first time in a very long time that I felt actual fear, reading a book. So, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about horror versus gore in your work.

MJ: Oh, God. That’s a good question. Because the way I plot this trilogy: this one is more picaresque, adventure, odyssey. The second one is probably more historical, magical realist. And the third one is gonna be mostly horror.

TO: Oh boy.

MJ: Well, let’s talk about horror. One of the things about horror, as opposed to gore, is that horror is a seduction. Dracula has to lure you first. The wolfman is seductive. He’s gonna rip you to shreds. But maybe he’s not.

TO: He’s a looker.

MJ: It’s the wild thing. And horror is a seduction. And I think if you’re gonna write horror — and I like using horror elements — you can’t forget the seductive part. I will lure you in and I will make you regret it within an inch of your life. But the important part is the lure. And that’s what I think the torture porn people never understand. How is it you’re gonna get to the old house? You’re not gonna go to the blasted house on the hill! You gotta have the lure to the haunted house. At the same time, I quite like gore. I like explicitness. I like pushing on the boundaries. For lots of reasons. Let’s talk about violence, for example. My violent scenes are very violent. But this is how you know it’s not pornography — at least, I hope it’s not pornography, in that you don’t get numb. If the violence hits you every time, that means it’s intense, but it’s not pornography. If you’re reaching the point where you just glaze over, then it has gone into pornography. And it’s no longer violent.

TO: There’s a lot of sexual violence too, and that, I think, makes me think of the queerness aspect and masculinity and male aggression and all these things that are sort of working together.

MJ: And that’s tricky because this is something I wrestle with, and I have my students wrestle with, all the time. When you’re dealing with things like sex, violence, rape, and the attitudes behind it, did you write a book with misogynists or did you write a misogynist book? Did you write a book with homophobes or did you write a homophobic book? Did you write a book that doesn’t flinch from violence against women or did you write an anti-women book? There is violence in it, there’s also sexism in it. I mean, Tracker is a prick. But is the behavior being called out? Somebody says to Tracker very early on, “are all women witches to you?”

When you’re dealing with things like sexual violence, did you write a book with misogynists or did you write a misogynist book?

TO: And Sogolon gives as well as she takes.

MJ: Precisely. To me, the solution is not to turn away from all of that horrible violence. It’s to make sure that you establish context. These women exist in a capacity other than victim. But at the same time, there’s nothing sinful about the status of it. It’s something that was done to you. There’s sometimes these weird kinds of books and films that are super violent but victim-blaming. And I wasn’t gonna do that at all. I remember, with first book I ever wrote, John Crow’s Devil, years, years before it came out, also a brutal book, a person read it and said the writing is okay, but I don’t have a clue about women. And I said “what are you talkin about? I have a mother, I have a sister.”

TO: The Matt Damon defense.

MJ: And she said, “I bet you don’t read any women” and that was true at the time, certainly no living one. And she put me on a diet of Toni Morrison. And the thing about the Toni Morrison books that struck me — particularly The Bluest Eye and Beloved — is there’s a lot of cruelty in those books. Because I thought the solution was “don’t be cruel.” Don’t put cruelty in the book. And don’t have your female characters do irrational things. And she said, “no, you’re missing the point. That’s not the point, they can do irrational things.” In Beloved, you have to come to terms with the fact of murder being an act of love. The thing is, are you giving these people humanity, are you giving these people agency, the capability of change? And I think if you do that, then yeah, they can do cruel, horrendous, brutal, terrible shit. Because in the absence of that, I’d have just gone from the ignoble savage problem to the noble savage problem. Yeah, everybody’s virtuous, they’re still cartoons.

TO: That reminds me of N.K. Jemisin’s Broken Earth trilogy, this mother-daughter epic, wherein they both have the power to essentially break the world, and they both do, over the course of the trilogy, really horrific things. At the same time, it’s not just that you’re rooting for them, it’s that they exist as full characters with agency. There’s cruelty in this world, and cruel things are happening to them, but it doesn’t feel like pornography.

MJ: As the reader, you never get the opt-out clause. You’re gonna have complicated feelings about these characters. Which is how it should be. I learned that writing Book of Night Women, my second novel. Where my protagonist makes a lot of bad choices, which cost a lot of lives. But you still kinda have to root for her. And I like when a book takes me through the ringer. And I feel exhausted in a good way at the end of it.

TO: Have there been any recently that have done that for you?

MJ: Maria McCann’s As Meat Loves Salt. Which is a historical novel. It’s been years since I’ve seen a book go so far out on a limb with a character — the character does some of the most horrific things I’ve ever seen. And I remember thinking “wow, wow, you’re going there, you’re going there, I don’t know if I can do this, I don’t know if I can do this, I don’t know if I can hold on.” There’s a scene where this guy just got married but the king’s army has caught up with them and they’re gonna be hung. He escapes with his brother, and his brother ends up seriously injured. And they have to get away, but he’s so upset that his wedding was violated. At the very least, he’s gonna consummate his marriage. So, he basically, in the presence of his battered and bruised, near-dead brother, on the run, stops to rape his wife. And I’m like “I don’t know, I don’t know. I don’t think I can do this, I don’t think I can do this.” And I can’t believe she wrote this. And yet, I stuck with it. And, somehow, she makes me fall for him again. It was the first character in years that I would lose sleep over because I’m frettin’ over this guy. And when he reverts — total spoiler, for whoever’s gonna read it — when he reverts back to what he was before, I felt personally betrayed. I was like I can’t believe you disappointed me like this. I’ve been here, stuck through all this shit with you.

TO: We were all rooting for you.

MJ: “I forgave you, dammit.” I don’t think any of my characters do things you can’t come back from, ever. That was a risky thing she did with that book. But a book should leave you changed. A book should leave you a little knackered. It should leave you a little messed up.

TO: It’s often said you announced your intention to write this African Game of Thrones. If Wars of the Roses was George R.R. Martin’s analog for Game of Thrones, what’s the analog for Black Leopard, Red Wolf? Is there a specific when and where?

MJ: I was trying the hardest to follow the rise of the Iron Age. A lot of African societies didn’t have a Bronze. They went from stone straight to iron. But I was also hugely inspired by imperial-era Ethiopia. And the palace intrigue. To the point where I think I might still write a historical novel based on it. I mean, it was like reading Henry VIII. I don’t know if there’s any one text or one period. I was also reading a lot of Plantagenet when I was writing this book. Largely because I think if you’re gonna write war or the rumor of war, it should be plausible. I was reading, not just the Odyssey, but all the Scandinavian sagas, Njáls saga and all of that. A lot of African epics that have been translated, a lot of Sonjara and Askia Mohammed. Ultimately, I had to go my own way. Because, one, one of the things about all these ancient stories is they’re all about kings. They’re all about the kings, they’re all about the fall of a royal house. It’s fine. But my book starts in the streets. Hell, it starts in prison. And for that, there’s less precedent. Why would there be? All the great dramas, the ancient stories, have always been about important people: kings, princes, princesses, queens, gods. If there’s a Greek epic about a barber, it hasn’t survived. So, a lot of Ovid, The Metamorphoses. But also, a lot of comics. Whether it’s Hellboy or B.P.R.D., the whole idea of misfits brought together is something I’d have gotten from comics, I’d have gotten from X-Men or New Mutants or Alpha Flight. Or all the supporting characters in Hellblazer.

TO: One of my favorite storylines in any medium is X-Cutioner’s Song. It collects, Uncanny X-Men, X-Men, vol. 2, X-Force, and X-Factor. It was back in the day when they did these cross-book storylines (that’s why trade paperback was always an absolute godsend). Cable comes back in time to assassinate Professor X, and Apocalypse is involved somehow, and it’s all about the Summers-Grey bloodline. And it has all the epic feeling of these 700-page fantasy books.

MJ: See the 700-page thing to me was also Sandman. Cause that’s how I read them. Trade paperbacks. To me, I was reading novels. “Dream Country,” “The Kindly Ones.” I read that as a huge volume put together. I have said to anybody who would listen to me: the best American novel of the past 30 years is Palomar by Gilbert Hernandez. And Death of Speedy [Ortiz] is pretty close.

If you don’t get that [epic feeling], it’s a failure. It’s a failure of fiction, it’s a failure of speculative fiction. In that sense, I’m as inspired by film as I am by novels. You know, it’s like the first time you saw the Death Star. Or the sort of nightmare-scapes in Alien, which all seem like an insect turned inside-out. As a writer, I’m as inspired by Rick Baker as I am by any novelist. I nearly missed my own book signing line to go line up for Mike Mignola.

Everybody assumed I came out of some ghetto and survived gunshots; no, I came out of the suburbs and survived boredom.

TO: That is definitely relatable.

MJ: I wonder sometimes if it’s a response to growing up in suburbia. It never stopped being funny: when Brief History came out, everybody assumed I came out of some ghetto and survived gunshots; no, I came out of the suburbs and survived boredom. One way in which you survive that is just to vanish into any world you could. And I was always in some other space. To the point where I’d have a fully-realized story all in my head because I would rehearse it so much. Some of these characters in Black Leopard, Red Wolf existed for years. I just couldn’t figure out what their story was. And the worlds themselves. I just love the idea of imagining something that is so foreign. Here’s what I wanted to resist: I think we do this kind of “yeah we’re gonna imagine, but we’re still gonna keep it tethered to the conventions of reality or the conventions within scifi.” And I didn’t want to do that, because that would then just be regular scifi with dark-skinned people.

TO: You’re just race-swapping.

MJ: You’re writing Tarzan in brownface. And I didn’t want that. What I think, for me, made sure didn’t happen was while I’m reading all these African epics, I also have to read their value systems and I have to read their ideas of right and wrong. Circumcision, including female circumcision, becomes confronted in the book. The idea of the world being round, but we’re living inside it. But they still got the whole idea of the world being round way early. Vampires who are perfectly fine killing you in the daylight.

TO: Yeah, there’s just a lot of cool shit in the book.

MJ: (Laughter) There’s a lot of cool shit. I kept thinking, “God, the childhood I would have had if some of these were out.” I don’t have plans to write YA or for children, but we need new myths, man. We need new old myths. They’re not new, I just didn’t know them. Some of this I grew up with, like Anansi, but it says something that most of the creatures in my book are part of the African mythology, history, but I had to go learn them at flipping 40. A lot of the research I was doing was source material. Original research papers. I read a lot of the African epics. And people reading them will read them with a very Orientalist eye. And the people who translate them also translate them with the Orientalist eye. But if you apply that eye to any text, then even the Iliad is not gonna sound great. So, what we have is a lot of scientists and anthropologists doing really good work, but most of those epics haven’t been translated by a poet yet. And a poet who understands griot verse. We’re still waiting for an accurate English-language Lion King. It’s not quite there yet.

TO: I think this speaks to the larger oral tradition, the importance of griots. Tracker even says to a character towards the end “You know no griot” as though that’s a curse. And characters throughout the novel want to know the How of things, not even necessarily the Why. Break this down for me, tell me the story.

MJ: One thing that I had to be very mindful of and very careful of is, again, not allowing any place for Westernism or Orientalism to slip through. One easy area it could have slipped through is the idea that oral cultures are primitive. So, when he says “you know no griot,” it’s a sign we’re an oral culture, and I’m important enough that somebody’s gonna recite my story in verse. Because I think it’s very hard for people on this side of the world to let go of the idea that an oral culture isn’t just as sophisticated. They just have different systems. “Oh, I got that person who’s gonna record it for me, and he better learn it by heart.” Which is why “you know no griot” is actually a pretty devastating diss. It’d be like me telling you “you know what? History’s gonna judge you a minor person.” As soon as you die, you’re forgotten.

One thing that I had to be very mindful of is not allowing any place for Westernism or Orientalism to slip through.

TO: I just finished watching Narcos: Mexico, and towards the end, one of the characters, you start to hear a narcocorrido of them. This song lionizing famous drug traffickers. A recording of history that shined a spotlight on particular people. And I see the same thing here with the emphasis on the oral. I mean the whole book is essentially: “here’s what happened.”

MJ: The one thing the ancient epics — and I include the Bible in this — have in common is great orality. Robert Alter translated the Torah, and he made a change. In the Bible, it said from the dust came Adam. Okay, fine. He changed it to from the humus came the human. It completely changes it. Because the thing Alter remembered is that these books were written to be read aloud. And that was very important to me. It was really interesting hearing the guy doing the audiobook for this. He was very happy. I wrote it to be read aloud. The problem is, he read it too damn good. The griot parts, he sings it. Dude, you can’t do this.

TO: So, the audiobook is, like, a qualitatively different experience.

MJ: Goddammit, dude, you’ve turned the audiobook into the definitive version of the fucking book. ’Cause I am not singing no shit on the book tour.

TO: It’s almost this circularity, right? This story that’s modeled as an oral history gets written down, and then is — it’s interesting to see other, non-Western storytelling traditions interact with Western modes of production.

MJ: Yeah, I’m still a child of West. I was born in Jamaica. I live in America. I love rock and roll. Rock and roll’s black, but still. What I had to get rid of was the value system. I know everything about the Celts and the Druids and so on. But knowing about griots and fetish priests and the orishas.

TO: The Igbo pantheon as well.

MJ: The Dogon pantheon is fantastic. Nobody had to tell them that there’s a sun and all these planets are swirling around it. They have this dance where this person holds a ball with a string, and the guy’s spinning, and after a while, you realize, holy shit, that’s the atom. Hold on, that’s the solar system. He knows exactly what he’s doing.

TO: I encountered some of this when I was doing research for my second book. I learned where the word algebra came from. It’s Arabic, al-Jabr. Which means “the reunion of broken parts.”

MJ: That makes me want to do math, and nothing makes me wanna do math.

TO: There’s this interesting intersection of mathematics and, more largely, science, and the divine. Rather than being competing ways of organizing the universe, they are complimentary. You can’t have one without the other. It’s not just prayer. It’s that numbers are a language through which God speaks to us.

MJ: Religion is practice, and algebra is practice. But I also think being non-Judeo-Christian has a lot to do with it. The thing about us on this side of the world is that even if we’re not religious, we’re all Calvinists. We still believe hard work plus reward is a sign of a meaningful life. One child shall lead us, or one hero or man is man and woman is woman and blah blah blah. Somebody asked me, they thought the queerness was the way in which I’m trying to punk or subvert the narrative. I was like “dude, those are the oldest elements in the book.” Non-binary, gender fluidity, shapeshifting, queer, gay, bisexual. Some African tribes, there’re 15 genders. My friend, Lola Shoneyin, on Facebook once, somebody asked her “do you think Africa will ever be ready to accept things like homosexuality and blah blah blah?” She said, “Africa was born ready.” Until a bunch of TV preachers from America told them they weren’t. None of those elements are new. Shoga is not new.

TO: It reminds me of Freshwater, actually. There’s this blend of the animist and the religious or divine elements with the very corporeal question of how we occupy our bodies. That seems very much in line with what we’re talking about with regards to these other ways of being in the world. So, you started researching this after having turned in Brief History, so before the Booker stuff and before it took off — did you ever feel that you had to walk this line between the book you should write and the book you wanted to write?

MJ: Oh, absolutely. Especially post-winning that Booker. The very first research on this book, I think I did in August 2015. As soon as I finish one book, I’m on to the next. Cause I have no life.

TO: (Laughter) Nature abhors a vacuum.

MJ: But I knew there’s a certain kind of book people expect a Booker winning or a literary establishment favoriting book writer to write. There’s nothing wrong with all of those books. And I remember talking with my agent about this. I have two ideas. I have this idea, which is a quite practical idea of what I should write next. It was lowkey, it was gonna be short, it was gonna be this quietly devastating indie book. And there’s this thing I really wanna write. And I remember she’s saying, “well, the other one seems like a more logical choice.” But she could pick up that I really wanted to write this book. I still believe this, you should write the books you’ve always wanted to read. Even then I thought, I don’t know how this book would happen. One thing my books have in common is they start from a place of impossibility. They all start from “I don’t know how the hell I’m gonna write this.” This one was worse! There was all this research, all this stuff I loved. That was still not a book. There are so many trial and error versions of this book, including quite a few written in third person. I just didn’t know whose story it was.

TO: So, you split the difference. The trilogy style is Rashomon.

MJ: That happened because I was having an off-hand discussion with somebody about the TV show The Affair.

TO: In keeping with this theme of unreliable narrators, which has much higher stakes given the centrality of oral culture.

MJ: Truth is your job [as the reader]. It’s not my job to convince you that I’m telling the truth. It’s your job to decide whether you’re gonna believe it or not. There’s an ownership of truth, but there’s also an accountability where you are a part of whether this truth endures. Which I found profound when I was reading a lot of the African stories. Some of that got translated to this side of the world. They couldn’t kill it off the slave ships. The idea that the trickster tells the story. In Jamaica, we have a saying. Nobody understands what it means now. At the end of a story, the storyteller says, “Jack Mandora.” And the audience says, “me no choose none.” Which, translated, means “I’m done with my story, do you believe it?” And I go, “no. Tell me another one tomorrow.” You’re gonna have to choose. I’m not telling the reader which of these three versions you should believe. You can believe all three or you can pick. There’s no secret Book 4 coming. No “authentic” version. You’re gonna have to choose. Or maybe you think all three people are lying.

Truth is your job as the reader.

TO: The reader is implicated.

MJ: The reader is absolutely implicated because you may choose the liar.

TO: One thing that I was wondering about — some of this is drawing on current and acute identity crisis — but I was wondering if you thought at all of the idea of diasporic African writers drawing from the Continent in this very particular way. Writing AfrArcana?

MJ: Well, as someone who just did it [laughter] I think there’s a lot of things at work here. It’s a reach for connection. I think as children of the diaspora we have a right to that thing. I remember reading a very stupid article years ago saying that black people can culturally appropriate. And I was like “Sweetie.” It’s one thing if I step into my father’s closet and try on his shoes, even if I don’t know the purpose of shoes. There is difference between that and me going to my next-door neighbor’s house and stealing their shoes. There’s a difference. I have a right to my mother’s house. I have a right to my father’s closet. We’re in the diaspora for a reason!

TO: That’s a whole other interview.

MJ: In the same way I would never stop an Irish-American from writing a book about Irish mythology or anyone from Minnesota writing a Viking novel. It’s legacy, it’s family. I have a right to those myths. Any person in the African diaspora has a right to those myths. Because of our background and because of what we know, we can interpret them differently. That’s the great thing about this kind of storytelling. The story changes depending the teller. That’s why there’s already like five or six versions of the Sundiata Lion King story. The whole idea of Authentic Version or Director’s Cut or ‘This is the true version’ makes no sense. It does not apply. So African storytelling has already made the space for our kind of voice. It’s already made the space for it. I do have a right to claim it. But I also think we all bring something else. That’s the great thing about speculative fiction and scifi. Ultimately, we’re all pulling from the myths and the myths are for everybody. How else are we gonna learn about themselves?

I think there’s a certain Westernness we can sometimes bring to that kind of story. For example, the whole idea of will and agency. The idea that not everything is fated by the gods and that the human will plays a huge role. I’m not saying it’s something the Western people came up with — you can find it in African storytelling — but I know it’s my western upbringing that taught me that. To me, all of this information was just this huge reservoir that I got to pull from in much the same way Tolkien would have pulled from the Celtic and Scandinavian or George RR Martin pulling from Wars of the Roses or whatever he knows about Asgard. That’s how old myths turn into new myths.

Any person in the African diaspora has a right to African myths.

TO: So, I was reading this. I got to the end. And one of the very first thoughts in my head was “I cannot wait to see how the fuck this is going to blow peoples’ minds.” I’ve never seen anything like it. The structural conceit, the elements of African mythology, the inversion of the quest narrative, all these different things coming together like lightning captured in a bottle. And I was imagining to myself, “how on earth is some poor reviewer from the Guardian going to handle this?”

MJ: I don’t know. I’m already thinking, “wow, this is gonna get some interesting reviews.” I don’t remember who, said it was “equal parts enthralling and enervating.” I was like “enervating? Sweetie, get some stamina. This is gonna be a rough ride.”

TO: You got two more after this.

MJ: The next story’s gonna be told by some 315-year-old witch, and she’s got a lot of shit on her chest.