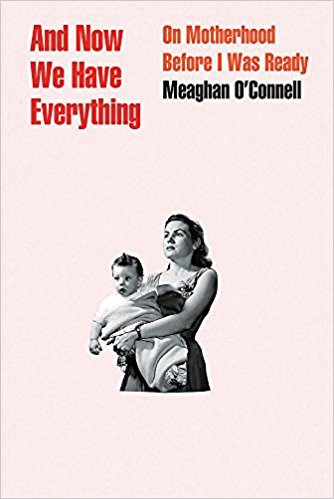

essays

Reading About the Worst Parts of Motherhood Makes Me Less Afraid

Meaghan O’Connell’s ‘And Now We Have Everything’ doesn’t sugarcoat pregnancy or parenting, and that’s why I love it

While reading Meaghan O’Connell’s And Now We Have Everything, I started to feel dizzy. She describes in excruciatingly pure detail how it felt to get an epidural while giving birth, and then have that epidural not work. I hadn’t known that was even possible, but through O’Connell’s experience, I learned that some pain can’t be quelled. Her epidural — which she hadn’t planned on getting — didn’t stop the baby from slamming into her uterus, “yanking the entire side of [her] body up and down with the contractions.” She described ligaments tearing away from her bones, causing pain so bad she said she wanted to die.

That’s when I started to feel lightheaded. Or maybe it was before that, when I read about the hollow needle that was inserted into her spine and the medicine that flowed through the needle into her body and felt like an electric shock. Or maybe it was reading about the hospital’s supply of what looked like giant knitting needles wrapped in cellophane used to break a woman’s water. (Actually, I’m pretty sure it was the description of the needles.) There are plenty of moments to choose from that may have made me feel woozy — giving birth is not for the faint-hearted.

But still I read further, faster, finishing the book in less than 24 hours. It was harrowing to read about, and likely brutal to experience, but I was grateful to hear about the horror of giving birth, and later, the struggles of parenting.

Though not yet a mother myself, I want to have kids, and like O’Connell, I find it to be a desire so vulnerable I almost can’t face it. When my fiancé and I talk about when we want children, a tiny part of my brain that I don’t entirely trust starts screaming, “Soon! Now!” But to say it out loud feels too precious, as if the world would hear me and punish me for being brazen enough to want something so good.

I have always been interested in reading stories about becoming a mother, as if it’s something I can study for and ace. I’m not worried about the good parts: I know I’ll love my hypothetical children; I know my fiancé will make a great father; I know there will be moments of joy so profound I can’t yet imagine them. I don’t feel like I need to prepare for the good parts. If I’m lucky enough to experience them, I’ll be glad when they happen.

I’m worried about the bad parts — the parts so bad no one wants to admit them. I want to prepare for motherhood by hearing about people surviving their worst days. I’m begging to hear about the nights you didn’t think you’d make it through without screaming, or when you were in so much pain giving birth you weren’t sure if you’d survive. I’m craving stories of being a human woman and making mistakes and coming out the other side. Hearing how women survive the worst parts of being a mother makes me less afraid to become one myself. When women like O’Connell talk about the hard parts, it lets me know that I’m not alone — that it’s not abnormal — if I should face them, too.

I’m craving stories of being a human woman and making mistakes and coming out the other side.

O’Connell balances the darkness in her story with moments of pure joy. I felt dizzy reading her birth story, but I cried tears of joy when she described her partner joining her in the operating room and both of them meeting their son.

I feel bolstered with this information — the bad with the good — and more ready to face whatever challenges may come. I imagine it’s the difference between wandering tunnels in the dark, and wandering in the dark but once having seen a map that leads to the light. It’s knowing there’s a way through because someone has been there before.

So I search the Internet for birth stories with complications and I read up on painful mastitis. When I read a particularly gruesome detail in And Now We Have Everything, I read it out loud to my fiancé, so that he would be prepared, too. (I ended up reading every particularly painful, funny, or insightful sentence out loud, which is to say, most of them.)

O’Connell writes about both the physical pain she felt, and the emotional turmoil of becoming a new mother. She experienced postpartum depression without realizing it, though I expect even mothers who don’t probably still experience some nights of despair and some moments of shock.

I found myself relating to O’Connell as she described the self-doubt she felt when she was pregnant or as a new mother, especially when she cried in the backseat of a car or in the middle of the street. I recognized myself in those moments, and I feel like that’s the kind of pregnant woman and mother I will be: one who cries a lot. When I’m depressed I cry about nothing, when I’m overwhelmed I cry about everything, when I’m happy the tears just fall like rain. Even not pregnant, I have cried in the middle of the street. If I get pregnant, I will definitely cry, but through my tears I will remember O’Connell crying and the insightful charming words she wrote about it, and I will know she stopped crying eventually long enough to write them, and that will give me hope.

There are stories of male pain everywhere in American culture. Jokes about men getting hit in the crotch are played for laughs for audiences of all ages. People are expected to get references to morning wood and blue balls, and there are names for those experiences. Women’s pain — especially physical pain, especially pain about motherhood, which is often construed as women’s One True Purpose — has fewer words to describe it and fewer shared stories in American culture.

Women’s pain has fewer words to describe it and fewer shared stories in American culture.

And Now We Have Everything is part of the growing canon that breaks down female pain and puts it into words. I have a ravenous appetite for this genre, and a deep need to share my own painful stories with those who will listen. I need stories of struggle more than I want stories of heroism, though in my eyes O’Connell’s story includes both. In an interview, O’Connell said she was writing “in the spirit of ‘Can you guys believe this shit?’” By translating her specific experience of motherhood into a language the childless or the uterus-less can understand, as if talking to a friend about some particularly good gossip, it becomes a story to be shared. It feels like reading an adventure story — a quest, but through birthing classes and daycares, like Harry Potter with pacifiers and amniotic fluid. O’Connell is the Woman Who Lived, only her obstacles were nursing, postpartum depression, losing her sex drive, hearing the cries of someone she loves immensely, and birth itself.

O’Connell writes about having dreamy ideas of the perfect birth and feeling like she failed, in part because of a book she read that seems to romanticize the process. After she had given birth she listened to a podcast that interviewed that author, where the podcast host confronted the author about portraying birth as a relaxed process instead of the violent one so many women experience. When she heard the author admit that for some women it is indeed painful and it is indeed difficult, O’Connell felt relief and forgiveness for a feeling of failure she had been holding onto. She writes:

What if, instead of worrying about scaring pregnant women, people told them the truth? What if pregnant women were treated like thinking adults? What if everyone worried less about giving women a bad impression of motherhood?

To this, I add my own addendum: What if having negative feelings about some aspects of motherhood didn’t make you a bad mother? What if, in fact, having negative feelings about aspects of motherhood, and expressing those feelings, and seeking them out as common experience, actually made you better?

Talking about motherhood is already so charged for some women, with pressure to breastfeed, or not; or work, or not; or sleep train, or not. I’m already worried I won’t be able to breastfeed and I’ll have to explain to everyone in my life why I can’t. That I even have this anxiety before I have kids seems toxic, but it’s real. That’s why I search out these stories of women who became mothers before me and struggled with it — to preempt my own feelings of failure and to try to forgive myself before they occur. I don’t view O’Connell as a failure; I see her a success, and I hope that’s how I will see myself, even if I get knocked down in the process. And Now We Have Everything isn’t a book of parenting advice, but a story of the unvarnished reality of what becoming a mother meant to one woman. And for me, that’s a survival guide.