Books & Culture

Miami Dispatch: Unmoored Realities on the Campaign Trail

Hijacked Airplanes, Candid Camera, and Donald Trump

Hijacking 1969

Shortly after the flight left Newark, a man walked a stewardess up the aisle of the airplane, past all the passengers, with a ten-inch steak knife pressed against her throat. A moment later the pilot, Captain Jack Moore, was on the intercom. “Well, folks,” he said, “it looks like we’re going south of Miami today.”

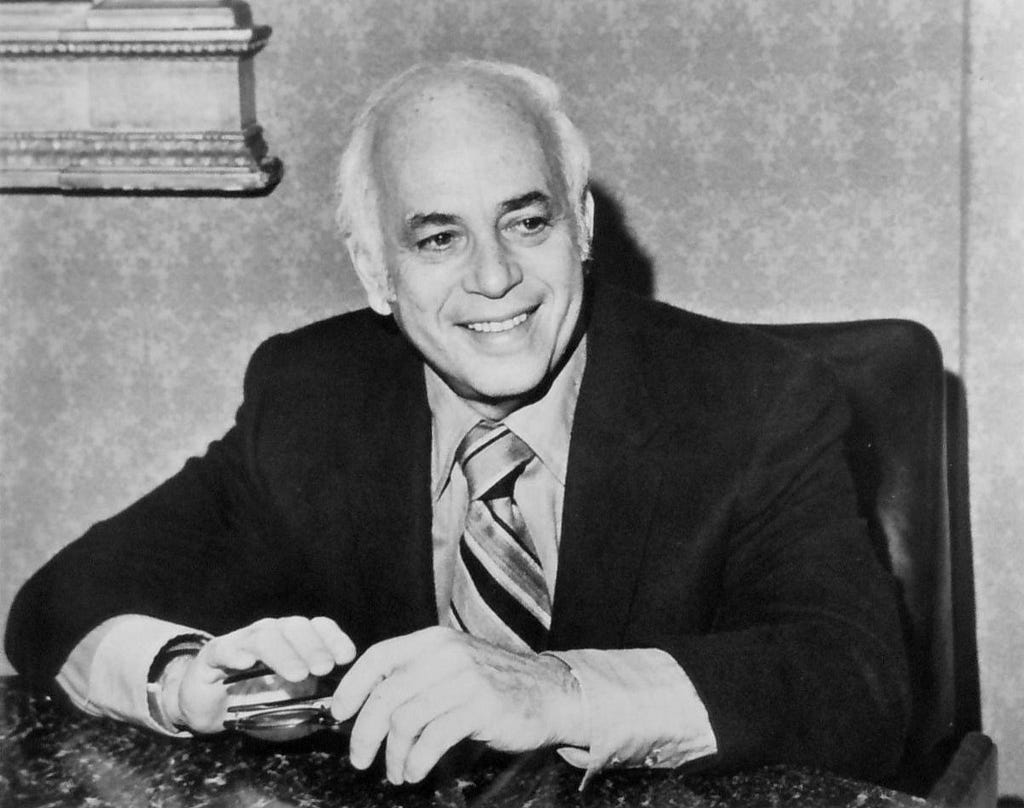

A particular fear of hijacked planes had lingered over the country for years. It caused people to board planes cautiously, eyeing each other, pointing out those who looked suspicious. And now their fears were confirmed. Panicked cries rang out, voices pleaded, but there was nothing to be done except to wait for their fates to be decided. But then, suddenly, their pleading prayers were answered. There, sitting in first class, hidden a bit from the open aisle, was Allen Funt. News spread among the terrified passengers; sighs of relief echoed through the cabin. According to later reports, people lined up with their sick bags to get autographs and stewardesses popped champagne. A new certainty took over: This was all part of a show. None of this — the hijacker, the knife, the threat — was real.

Landing in Miami

A voice says, Her thirty years versus his.

Then a second voice: At least his thirty years have been successful years.

Success for himself only.

What’s wrong with that?

What do I care if he’s been making himself rich for thirty years? How is that the necessary qualification?

My driver turns down the radio. “How come you don’t know how to get out of an airport?” he says to me, not trying to conceal his anger.

“I’m sorry,” I say. I was supposed to meet him in the arrivals landing, which was a level below where I’d stood, looking for his car. The driver called me yelling that I was in the wrong place and that he would leave, but I asked him to wait and he did.

“You don’t pay attention,” he says. My receipt would tell me later that his name was Sergio. “If you don’t want to pay attention, you just take the bus or something. Don’t waste my time.”

It is raining in Miami. My plane had landed at the same time as Air Force One which caused delays on the tarmac. President Obama is scheduled to give a talk about healthcare that afternoon at the University of Miami.

“You never seen an airport before?” Sergio says. A sullen French woman named Corinne is sitting next to me, sharing the ride. She, too, had failed to go to the arrivals level and Sergio had stood outside his car yelling, “Corinne! Corinne!” He tried to explain, screaming into his cellphone, that she, like me, was waiting on the wrong level, but he spoke with a heavy accent and she spoke almost no English. As I listened, it occurred to me that I could have offered to help — I spoke just enough French — but I said nothing. I wanted to see how the plot would unfold. We found Corinne eventually, but not before Sergio had wasted thirty minutes on our mistakes.

I look past Sergio to the wave of cars standing still on the highway ahead us. I’d overheard a flight attendant complaining about what the President’s motorcade would do to traffic.

“You don’t have airports where you’re from?”

“Different airports are set up different ways, I guess.”

“Where’d you fly in from?” says Sergio.

“New York.”

“Oh,” he says, his tone changes. “New York City?” We are suddenly on the same team. “Manhattan. So beautiful. I love Manhattan. You live in Manhattan? I got a cousin who has a friend paying $3,000 a month to live in a shoebox in Manhattan.”

“I live in Brooklyn.”

“When I first came to the states, I lived in New Jersey,” he says. “I went to Manhattan a few times. So beautiful. But better is Spain. I’m Cuban, but I went to Spain for a few years. Now I’ve been in Miami for ten. Miami is good, but Europe is better.”

Rain pummels the top of the car. A voice on the radio claims that Hillary had won the debate the night before, the third and final debate of the election. Sergio scoffs.

“Did you watch the debate last night?” he says. Corinne stares into her cellphone as if down a deep well.

“Yes,” I say.

“They’re talking about Hillary like, ‘Oh, I guess she was the winner.’ But of course she was the winner. People think maybe she didn’t win just because Trump survived without too much nonsense. That puts him in the running? I don’t think so. It’s amazing what people can get used to.”

“People think maybe she didn’t win just because Trump survived without too much nonsense. That puts him in the running? I don’t think so. It’s amazing what people can get used to.”

Captain Moore heard the commotion from the cockpit. It was not the first hijacking for Moore who would later tell the press that it was “easier the second time around.” It was the twelfth hijacking that year, the fifth for his company, Eastern Air Lines. It wouldn’t even be the only hijacking of that day. Later, in another part of the US, a young American man, a student, would hold a hairspray bomb to the head of a stewardess. The student told her he would be eligible for the draft in six months and that he did not believe in war and wanted to live a simple life of hard work in Havana. It was February 3rd, 1969. He cried as he begged to be able to leave the United States. His girlfriend stood by silently, staring down at a black leather flute case in her hands. Between 1968 and 1972, planes were hijacked and forced past Miami to Havana with shocking regularity. When the student and his nervous girlfriend made their attempt, the stewardess walked in the cockpit and to the pilot she casually said, “Guess what?”

“I’m not a citizen,” says Sergio, “so it doesn’t matter what I think, but if I could vote, man, it would be a very hard decision for me. Very hard choice.”

“Really?” My surprise is audible. “Does it bother you what Trump has said” and then I add tentatively, “about immigrants? You’d still consider voting for him?”

“He doesn’t mean it. Everyone knows that. He doesn’t hate immigrants. It’s all a show. Look, his mother is an immigrant. It’s an act. His wife is an immigrant. He doesn’t hate immigrants. He just has to say it so get a certain type of voter. He’s performing.”

“Do you worry that his comments about immigrants, whether he means them or not, will stir up hatred? Do you fear that?”

“Me? No. I’m a Cuban living in Miami. This city welcomes me with open arms.” Sergio laughs and gestures out the window to a Miami blurred behind a sheet of rain. “It’s you, not me,” he says, “You are the stranger here.”

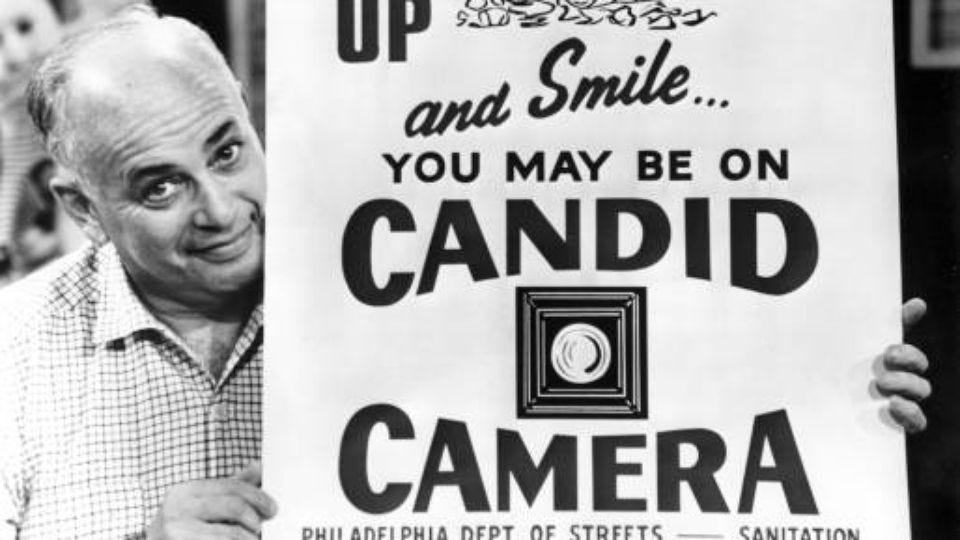

Smile… You’re on Candid Camera

Allen Funt was on the plane with his wife and their two daughters. He planned to shoot scenes on South Beach for his first film, a feature called What Do You Say to a Naked Lady? It was to be made in the style of Candid Camera, Funt’s hugely successful television show which put ordinary people in unusual situations and filmed their reactions without their knowledge. In an episode which aired originally in 1953, an unsuspecting man wearing a nice hat goes into a shop and begins a conversation with who he assumes is the shop’s clerk. Allen Funt appears behind the man in the hat with a carton of eggs and says, “Let me see that hat for a moment. It is an expensive one, isn’t it?” The man nods and Funt says he’d like to perform a trick. The clerk, who is really an actor, encourages the moment, “This guy’s a magician!”

The man does not want to give over his hat, but Funt convinces him and then proceeds to break raw eggs directly into its well. “Now watch,” says Funt and he covers the opening of the hat with a piece of paper and says a few magic words. Then Funt lifts the paper. The unsuspecting man sucks his breath in a bit with anticipation and peers down into his hat to find, of course, the raw eggs are still there. What he thinks is real, we, the viewers know, is just narrative set up leading to the conflict.

Candid Camera began as a radio show called Candid Microphone, the tagline for which was, “The show that brings you secretly recorded conversations of people in real life as the react to all kinds of situations.” Funt found out quickly that just recording ordinary people talking yielded incredibly boring results, in part because everyday conversations do not adhere to narrative arcs. By the time his show moved from radio to television, Funt figured out that if a conflict was introduced, it would force reality into a more interesting shape; and the more confusing and frustrating the conflict, the more compelling it was to watch people reacting candidly.

But the formula wasn’t perfect yet. Instead of humorous, the practical jokes often felt mean-spirited. A reviewer writing in 1950 for The New Yorker wrote that Funt was demonstrating how “most people are fundamentally decent and trusting and, sad to tell, can readily be deceived. Persuading his subjects that he is something he is not, he succeeds in making them look foolish, or in forcing them to struggle, against unfair odds, for some vestige of human dignity.”

It is painful to watch the man as he looks down at his ruined hat, and not just because he is excluded from the joke that we are all in on. It’s painful to watch him suppress his frustration for the sake of social politesse. His face contorts with the effort. His words come out first as a mumble. “You’re got to be kidding me,” he says quietly.

“For my money,” stated the review in the The New Yorker, “Candid Camera is sadistic, poisonous, anti-human, and sneaky.”

When the passengers on the hijacked plane see Allen Funt, they began to laugh and dance in the aisles. They made so much noise, the hijacker was alerted and when he emerged from the cockpit, knife in hand, the passengers gave him a standing ovation.

When the passengers on the hijacked plane see Allen Funt, they began to laugh and dance in the aisles.

South Beach 2016

Traffic eases and soon I’m given my first real look at Miami. I stare with greedy eyes and am struck with the feeling that I’d arrived, not in a city, but onto a set for a TV show. I’d felt this way my first time in New York City, in Los Angeles, in Venice, all real places made familiar to me first through a screen. It is my first time in Miami and yet I know it well. Here come the opening credits.

Tomorrow I’ll be sitting in the hot sand on South Beach, my sight jump cutting from scene to scene of the expected: neon swimsuit, beach umbrella, big, big beautiful boys and babes, pink drinks, jet ski, speed boat. Directly in front of me on the beach I’ll see a group of teenagers who look as though they’ve made by a machine that spits out human bodies designed to reflect up-to-the-minute beauty ideals. The teenagers pass around a plastic bottle of vodka as big as a torso, each filling a red cup. The boys wear hats with the bills turned backwards, leaving their burnt cheeks and red noses exposed. The boys approach the girls, throw footballs too close to their heads. Girls squeal, girls giggle. More join in, some carrying cases of beer the color of urine. They grow so large in number that they block the shoreline from view. I think to move. There are other free spaces on the beach. I think to read my book or swim or take a nap, but I don’t because I’m riveted. I’ve seen enough to know that this scene will soon include either a shark attack or orgy. I’m waiting. Then, finally, some action. Police appear, but, to my dismay, they do nothing interesting. They warn the teens in low tones and leave. Bodies flood back together, now with voices, on edge, jittery with the encounter, and stuff up my view.

I’ve seen enough to know that this scene will soon include either a shark attack or orgy. I’m waiting.

What they don’t show you on television is how the officers are undermined by the sand sifting into their sneakers. They cut the scene where the cops lean against a railing somewhere up on the boardwalk, sweating in their black uniforms, gun belts digging in their soft sides, bending to unlace their shoes and shake them free of sand.

Teens dive in the water. A boy in the yellow hat pulls at a girl’s bikini top, successfully flipping it off her breasts and over her eyes. She stretches her arms out in front of her and staggers around in the waves. I look impatiently for a shark fin on the horizon.

Sergio drops me off at Garcia’s Seafood and Grille whose website promises me the day’s catch in a large open air space overlooking the Miami River, but when I walk in all I see is a stout woman behind a case full of ice and fish and, to her right, a long, narrow industrial kitchen. There are no tables and no customers eating; no one greets me or explains where I should sit. The woman at the fish case says something to me in Spanish, but I don’t understand.

I see a few stools pulled up to the kitchen’s counter and so I climb on one and wait. The woman glares at me, but says nothing. I watch the cooks in front of me ladle thick soups into bowls. They move quickly, shouting to each other in Spanish. A man wearing a blue Kansas City baseball hat emerges from the kitchen holding a sandwich. I think that at any moment he will notice me and ask me for my order, but he doesn’t. Instead, he leans against the counter and rips into his lunch. He stares blankly out the window ahead of him and eats. Bits drip from his mouth to the bare kitchen counter at which I, too, am sitting. His is the face of a boss on a break. He’s slumped forward, his elbows hard on the counter, but his expression is serious and I can tell he’s listening to everything that is happening in the kitchen behind him.

“Go Royals?” I say, but not loud enough for him to hear or maybe he does hear me and doesn’t care.

His eyes land on something and he stands up straight and shouts in Spanish over his shoulder. A voice from the back of the kitchen responds and the two speak rapidly until the front door clangs open and in walks a tall, white-haired man in a rumpled suit. They fall silent.

“My man,” this stranger says.

“Hey, Abe,” says The Boss.

“How’s the baby? Sleeping through the night?”

“I guess,” he lifts his blue cap and scratches his scalp.

“That’s a no, then.”

Abe runs a hand through what is left of his white hair and thuds a heavy briefcase onto the counter. He opens it and takes out some papers, they’re contracts.

“What’s up, Abe?”

“I got something important for you to hear. Something big.”

“Oh, yeah?”

“But first things first. You want the news?” and they begin talking to about someone they both know — a Yuniel — who’d recently left his wife for a lover. The lover lives in Abe’s building.

“You’d think I’d see him all the time now, but no,” says Abe. “He’s in there with that woman. He can’t stop fucking her, he can’t take his dick,” he’s talking too loudly now, “out of her long enough to say hello to his friends.”

“You didn’t talk to him about Lucy?”

“Of course I did.” Abe’s voice is thin and shrill, like he’s forcing an unpracticed accent. “I gave him hell. I said, how could you do it to Lucy? I said, I’m going to go over there and fuck her myself. How would you like that? I’m going to go there and fuck your wife. But he doesn’t care. He’s stuck inside this other woman.”

A younger man, a waiter perhaps, joins the two men at the counter. He greets Abe with a shy smile then sees me. He regards me curiously for a while and I wonder if he only speaks Spanish and so, to help the situation, I point to a special written on a chalkboard I see hanging in the kitchen.

“Please,” I say. And the young waiter nods slowly and then disappears.

All an Act

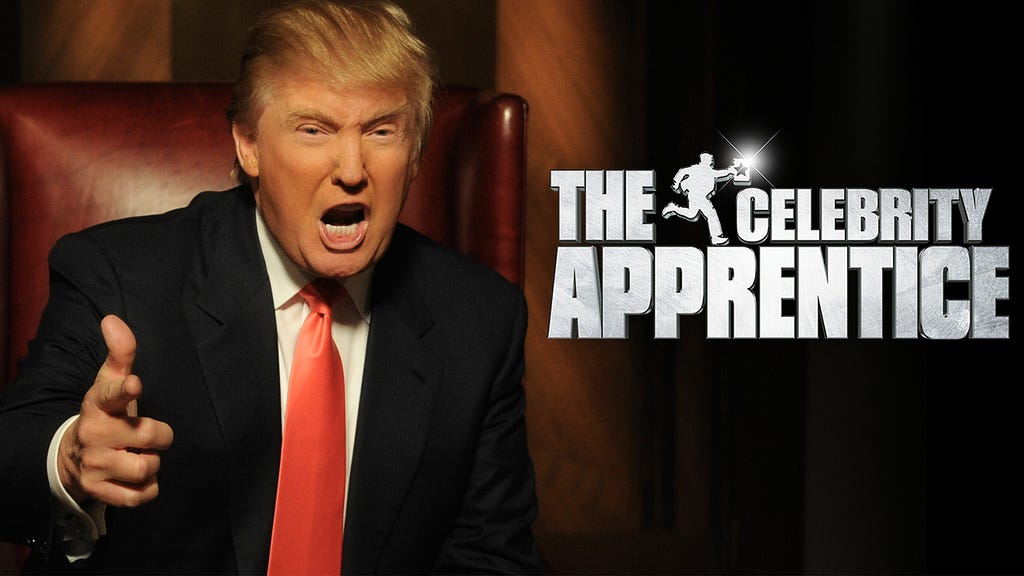

It’s not real. It’s a joke, an act, a performance for ratings; it’s for Trump TV, all a ploy, just bragging, just the way he talks, just the way men talk, it’s for certain constituents, it’s just all a gag, it’s for show, it’s just locker room bragging. But he’s a straight shooter. He doesn’t play politics. He says what he means. Except when he doesn’t really mean it.

But he’s a straight shooter. He doesn’t play politics. He says what he means. Except when he doesn’t really mean it.

Like Funt, Trump has a magic trick; somehow he has managed to bewitch a percentage of the electorate into redefining what it means to mean what you say. The morning after the third debate, Trump’s surrogates appeared on television news programs to say that — despite Trump’s claims that he may not accept the results of the election — Trump would, really, truly, actually, accept the results and, no, he didn’t mean he wouldn’t when he said he wouldn’t, what he meant was he would accept the results, that’s what he’d meant, trust us.

Later on, after dinner, I’d check into my hotel and then wander down to its bar and there, flickering before on a television mounted on the wall, I’d catch a glimpse of the great and powerful Trump, wiggling his fat, magician’s fingers at me, saying, “Ladies and Gentlemen,” he says to the audience. “I want to make a major announcement. I would like to promise and pledge to all my voters and supporters and to all of the people of the United States. That I will totally accept the results of this great and historic presidential election — If I win.”

My bartender laughed. I asked him what he made of such a statement. He explained to me in a heavy Haitian accent that I’d have to shoot him before he’d vote for Trump, not that he could vote anyway.

“But, at least he says outright exactly what he means. He’s not playing politics. Putting on a nice face in public and then hiding behind racist, anti-immigrant polices. No, he means, ‘Get out’ and says, ‘Get out.’ I respect that. With Trump, you know just what you’re getting. But it doesn’t matter. Everyone knows he doesn’t actually want the job. Every morning I wake up expecting to see news that he’s dropped out of the race.”

“But, at least he says outright exactly what he means. He’s not playing politics. Putting on a nice face in public and then hiding behind racist, anti-immigrant polices.”

It is possible that, before Allen Funt, we can imagine a time when we would not have thought of reality as so manipulated. Candid Camera changed that forever by introducing the idea that a strange occurrence might come with a plot twist. It originated what is now, in our current age, an advanced awareness that reality might not be real.

“Now, here’s the real news. Listen to this,” says Abe and he makes a show of looking over his shoulder and past The Boss and into the kitchen. “You like the Heat?”

“They’re no good.”

“Yeah, but you watch the Heat,” says Abe. “You go to the games.”

“They’re trash now.”

“Yeah, but you like the Heat.”

“Sure.”

“I got tickets. Forever I’ve had these seats. Amazing seats. Not quite court side, but VIP, I’ll tell you. Better than court side. You’re right there. You could reach out and trip Wade.”

“Wade went to the Bulls.”

“You can trip anyone you want.” Then Abe began a long story about how he knew all the big VIPs who sat in the lower sections of the arena and how they were mostly old-timers like him, and there’s was this one guy, old guy, who didn’t want his tickets anymore and had tried to give them to his kids, but they had families of their own and were too busy for the Heat and so this guy didn’t know what to do with his tickets.

“Could make big money on those tickets.”

“Yes, but you see,” and this is where Abe started to lose me. His voice wavered, betraying him. He was lying. “We have a sort of gentleman’s agreement, you see. We like to keep these tickets within a certain circle, you know, so that when we go to the games there’s someone to have fun with. Can’t sell the tickets to just anyone. Can you imagine?”

“Sure.”

“Exactly.”

“My old friend is out, he’s done with the tickets. He’s had them so long, they’re dirt cheap. Couple thousand for the season. Nothing to a guy like you, right? Amazing seats. And have you seen the women who sit close to the court? They don’t wear underwear. They spread their legs for the players and we get a free show. You wouldn’t believe these women. Fake tits don’t bother me. You get these tickets, we go to a few games, have fun, couple thousand. That’s it. The tickets stay in my old buddy’s name, but they’re yours.”

“I pay for the season, but the tickets stay in his name?”

“Yeah, but he don’t want them back.”

“Ok, but what if we pick up a good player in a trade, you telling me he won’t want his seats back then?”

“No, never. Listen, I know this guy thirty, forty, fifty years. He says he’s done with the tickets, he’s done.”

Abe is selling too hard and The Boss knows it. There are too many details, none of them specific. I look over at his contracts spread out on the counter and the scam becomes clear. He’s a lawyer selling off the assets of clients who’ve died, assets the family doesn’t know about or doesn’t care about. Sergio had told me just how rich people were in Miami. “You think you got rich people in New York and you do, but it’s a different kind of rich here. People have stuff here. So much stuff.” I wondered if it was common for rich people to have so much stuff that a lawyer specializing in wills could keep some stuff for themselves without the family noticing. If the Heat tickets were sold on an open auction, the family might find out. But if they were sold quietly and stayed in the dead guy’s name who would know? I was onto Abe and started to watch him very closely, taking note of his every move, cataloguing details, his clothing, the brand of his suitcase, the names on his contracts, because this is what the detectives I saw on TV would do.

“Give me your number,” Abe said to The Boss.

“Give me your card before you leave. I’ll call you if I’m interested.”

“Come on, give me your number. Where’s your phone. I’ll put my number in your phone and then you text me so I got your number. Your phone’s right there. I see it. Plugged into the wall right there.”

Abe notices me now. I writing all this down. He leans over clamps a hand on my arm. His hand is large and warm.

“What’s that, a diary?” he says.

“No,” I say too defensively.

“Don’t see many girls writing in a diary these days.”

“Writing notes for an article,” I say. “Obama is in town.” The two sentences are unrelated, but not false.

“Trump should be disqualified. The things he says! How is he not disqualified? What does it take, really? How did we all get so used to the vileness coming out of this man? Look at this,” Abe hands me his phone to show me a picture of a homeless man holding a sign that reads, Give me a dollar or I’ll vote for Trump. “Saw this guy yesterday downtown.” Abe flips through other pictures, most of which are Internet memes. He shows me an image of Bill Cosby with the caption, It’s easier to grab their pussies if they’re unconscious. “My buddies send this shit to me,” says Abe. “Best part of my day. I look forward to it so much.”

Abe hands me his phone to show me a picture of a homeless man holding a sign that reads, Give me a dollar or I’ll vote for Trump.

Very Real Danger

Allen Funt began to beg the passengers to listen to him. This is not a stunt, he pleaded, but no one listened. Women applied fresh lipstick and turned around in their seats, looking for the hidden camera. Sitting behind Funt was a priest with a serious look on his face. Funt turned to the priest and said, “Please, you have to help me convince everyone of the very real danger we’re all in.” The priest regards Funt for a long time and then slowly breaks into a smile, “You can’t fool me, Allen Funt.”

The public turned in favor of Candid Camera as soon as Funt added what can be called “the reveal.” At the exact moment when the man, gripping his ruined hat, seems ready to yell or cry or break something, Allen Funt puts his arm around him and says, “You’re a wonderful fellow. Let me explain. You’ve just been on a television show. See that camera behind there? Can you see it behind the glass?” The man nods. The truth has been revealed. He laughs with relief.

The passengers were waiting for the reveal that wasn’t coming. The plane skidded onto the tarmac in Havana and it was then that passengers realized the very real danger they’d laughed off. The Cuban military police burst through the cabin doors, rifles drawn.

Abe leaves and The Boss in his blue cap whispers to the young waiter who has reappeared, but not with my food. They go on like this in Spanish and then stop suddenly and look at me, both realizing at the same time that I am still there, watching them. I smile. My mother told me once that she thought I was brave to travel alone, not because I was in a new place by myself, but because I inevitably would have to eat alone. I think it is suspicious to eat alone, she’d said. Whenever I see someone eating alone, I think, ‘What’s so wrong with that person that they don’t have someone to eat with.’

The Boss walks toward me. “Let me ask you a question,” he says. “What do you think of that guy who was just in here?”

I don’t know what to say and so I say nothing, but my silence is read as too meaningful and The Boss lights up.

“See!” he says, pointing to me. “I don’t trust him either. For the last month he comes in here and sits at the counter like he’s my best friend. He’s talking too disrespectfully, I think. He thinks we like it. That’s what he thinks of us.” The door clangs open again and we all look up nervously. A couple walks in looking confused.

“Restaurant?” They say.

“There,” He points to a door adjacent to the one they’d come through, the one I’d come through. “That door and upstairs. This is just the kitchen.” I’m certain that my face is bright red with embarrassment. The woman at the fish case is looking at me with raised eyebrows. She points to the couple. I watch as they exit the kitchen and go through a different door, clearly marked with a sign that reads, “Restaurant.”

The Boss is watching me. “So, what do you think of that guy?”

I worry about what to say and buy time by looking as if I’m weighing my words carefully. He’s forgiven or chosen to overlook my invasion of this space, although the woman at the fish case has not. If I say the wrong thing, I’ll be ousted without my meal and I’m very hungry after a long flight and a long car ride with Sergio. I don’t know this man or Abe or this city, which, before this moment, I was pretty sure existed only to be a backdrop for crime shows. My plan is to shrug politely, say nothing, eat my food, and go. Speaking will cause trouble, that seems evident. I take a breath. The Boss leans in.

“It’s a scam,” I say gravely and then, just like a TV actor, I tap my notebook and raise my eyebrows. His eyes widen.

“It’s a scam,” I say gravely and then, just like a TV actor, I tap my notebook and raise my eyebrows.

“Oh! Wait? Are you keeping tabs on him or something?” Pieces of a false puzzle are aligning and though he clearly doubts what I’m saying, he also smiles, relieved. My presence has an explanation for him and I’m glad.

I’m hungry and I want to eat and leave. As I sit there, national polls are reporting results: The race is tightening. The Boss is watching me, waiting for me to tell him truth. I nod. Then shrug. My food arrives.