interviews

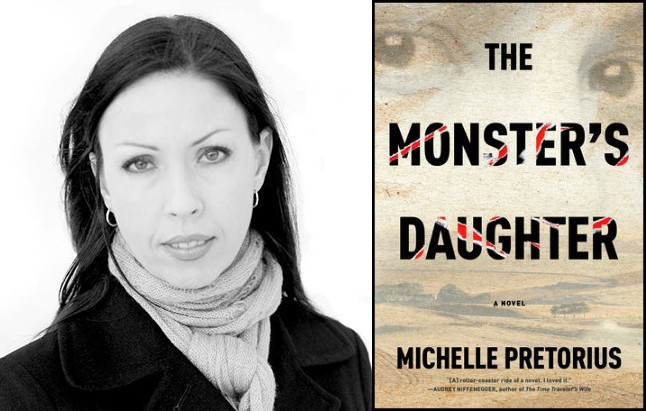

Michelle Pretorius Delves into South Africa’s Past

Talking Crime, History and Oppression with the Author of The Monster’s Daughter

Michelle Pretorius is no stranger to the complexities of history as it shadows the present. She was born in Bloemfontein, in the Free State Province of South Africa. She moved around the country with her family as she grew up, but she returned to Bloemfontein, a conservative stronghold, as a teenager. Apartheid and Christian-nationalist ideology were particularly pervasive factors throughout her life. It wasn’t until she left South Africa that she was able to see objectively how damaging this environment was, as she says, “not just for the society, but for individual growth and compassion as well.”

Now a PhD student at Ohio University, her experience inspired the writing of her debut novel The Monster’s Daughter, published in July by Melville House. The book spans over one hundred years, tracking characters from the time of the Boer War, through the rise and fall of apartheid, and focusing on a contemporary murder case that weaves the past and present together. It is at once a page-turning crime thriller, a richly written character study, and a cross-genre work of speculative fiction. Pretorius achieves a difficult feat, writing characters with compassion while deftly juggling suspense and multiple points of view to deliver a book that will appeal to a wide range of audiences. I recently spoke to her about the book and its origins.

Todd Summar: As a debut novelist, why was it important to you to tell this particular story as your first major project?

Michelle Pretorius: A teacher I admire very much once said that first novels are often thinly veiled autobiography. I think that The Monster’s Daughter was my way of coming to terms with my past and my role as a white person growing up in South Africa during some of the darkest days in the country’s history. We were under severe censorship when I was a child. The government controlled the media, books, anything that could possibly spread a subversive message. I think they even tried to ban The Beatles at some point. It is part of the reason South Africa only got television in 1976. Conservatives feared that the outside world would spread its immoral ideas and lead black people to revolt because they would get ideas about their station in life. In schools we weren’t taught the real history of South Africa, but rather a whitewashed history in which our Afrikaner ancestors were mythologized, their status in folklore akin to gods. In church we were told that God himself had given this part of Africa to the Afrikaner, that it was his right to be there. It sounds like a huge cop-out now, but it was only once I left South Africa that I realized that perhaps these things I was raised to believe, might not be the truth. I started reading and researching the true history of South Africa, the reason things happened the way they did. I don’t believe in one group being inherently bad and another inherently good. There was a reason the Afrikaners went from an oppressed minority, to the oppressors. I wanted to understand what happened, to trace the arc of events, and while doing so I also wanted to find some kind of truth. The novel grew out of that desire.

Summar: In Western literature, there seems to be a lack of representation of the immense political and cultural struggle in South Africa’s history, and the after effects of apartheid. People in the United States tend to ignore what happens in other countries. As someone now writing and publishing in the United States, did this notion drive your urge to tell this story?

Pretorius: When I first started working on the project, I was surprised to learn that nobody in the US knew about the South African concentration camps during the Boer War. I don’t fault Americans for not knowing South Africa’s history. After all, I actually knew very little of it when I first came here as well. The concentration camps were an obvious place for me to start the novel since, I believe, that is where apartheid had its roots. Yes, the country was colonized before that, and even the colonizing Dutch in 1652 had slaves and oppressed the non-white peoples of the land, but I’m talking about the institutionalized oppression that took hold in the country in the 21st century and the apartheid government’s rise to power. History is obviously important in the book. I also believe that aspects of South Africa’s history of race relations and oppression can be found in many societies, which makes it relevant beyond just a history lesson about what happened in one particular country. It is my hope that it might start a dialogue about what is happening in the US and other countries as well.

Summar: In some ways, the book serves as a dramatic snapshot of the history of apartheid, woven together with the very personal stories of its complex characters. How did you balance the massive amounts of research with such a nimble, elegantly-crafted narrative?

Pretorius: I’ll be honest, I failed miserably at first. When I started writing the novel, I made the rookie mistake of trying to tell readers every fact about the Boer War, in great detail. I forgot about story and characters, and didn’t trust my reader to figure things out for themselves. It took me a while to realize that nobody picking up a novel would be interested in reading a history book of facts. A personal connection with characters is the way in which you make the history real for the reader. Once you have strong, grounded characters you can place them in any situation, and you’ll know how they will react. I am what some call a “pantser.” I don’t plan my story ahead of time. I like to take the journey along with my characters, and see what happens — by the seat of my pants as it were! I took time to figure out who my characters were, and placed them in the turmoil of real historical events. I had quite a few sleepless nights, fretting about how things would come together. I did a lot of reworking and re-visioning throughout the writing process, and I learned to be ruthless when it came to cutting prose that wasn’t working. I was also very fortunate to have a group of intelligent and supportive writers who weren’t afraid to let me know if something in my draft wasn’t working.

I like to take the journey along with my characters, and see what happens — by the seat of my pants as it were!

Summar: The novel’s structure — interspersing the events of a murder case in 2010 with a timeline that spans the previous 100+ years — is a boldly original approach that heightens the tension and underscores the fraught history of South Africa. Was this tactic always apparent to you or did it take some experimenting to arrive at that point?

Pretorius: The past is very much a factor in our present lives, whether we know and understand our history or not. I wanted to illustrate that reach of the past into the present. Even though I intended to write a historical novel at first, I realized fairly early on that a present-day murder mystery would drive the novel, and that the historical fiction would inform the murder mystery. They are symbiotic in the book. It didn’t make sense to write the story chronologically, and so, even though it takes a while for the connections between the two narratives to form, I hoped that the individual strands would be interesting enough in themselves to keep a reader engaged until the connections between them became apparent.

Summar: Your decision to straddle genres, incorporating elements of crime thrillers, speculative, and historical fiction, will likely surprise and excite readers. What inspired you to verge away from a straightforward approach into this unexpected territory?

Pretorius: The story demanded it, in a way. As I mentioned, the crime thriller part made the historical fiction more relevant. We only experience history in segments, which is part of the reason the same mistakes get repeated. I wanted there to be characters that bore witness to these cycles of history, that saw the larger picture. That’s difficult in a human lifespan. And so I turned to science fiction for help to create these characters that not only lived a long time, but were actually the superior race that the Afrikaners claimed to be.

Summar: What is the significance of starting the book’s timeline with the events of the Second Boer War?

Pretorius: I was interested in exploring the arc of the rise and fall of apartheid. The Second Boer War was, to my mind, the point during which the Afrikaners were most oppressed and humiliated. As a people, they had suffered immensely during and after the war. It was this suffering and oppression that led to the exigency and emergence of the Broederbond, and the rise of Christian Nationalism, which in turn paved the way for apartheid. It was also a repetition of history i.e. the oppression of black people and suppressing their language (like the British attempted to suppress the use of Afrikaans after the war) that led to the ultimate downfall of apartheid.

Summar: The major threads of the story follow the parallel arcs of two women — Constable Alet Berg and Tessa Morgan, a young woman with supernatural characteristics born from sinister genetic experiments during the Boer War — though the cast of characters surrounding them play integral roles. When and how did it become evident that you would follow and mesh these two characters’ stories together?

Pretorius: Many writers will tell you that the first hundred pages of a novel are the hardest. That’s when you grapple with who your characters are, and try to figure out the what and the why of your story. Tessa and Alet formed independently. I took a few drafts of that first hundred pages for me to start thinking about the relationship between the victim of a crime, and the person seeking justice for that victim. They are both women, so I think Alet, who is a police officer, has an inherent understanding of the violence enacted on women. I wanted the connection to be deeper than that, though. The book is a journey of discovery for Alet, along with the reader, and Tessa is the key to that discovery.

Summar: The book is steeped in South African politics, culture, and folklore, such as legends like the Thokoloshe, as well as the conflict between black and white South Africa, the specter of apartheid, the death squads, the Broederbond, and more. As a native of South Africa, how did you ensure the authenticity and accuracy of each touchstone, while also avoiding turning the novel into a laundry list or encyclopedia?

Pretorius: Having grown up in South Africa gave me an edge when it came to interpreting the research, as far as cultural cues and practices were concerned. But if writing a short story is a 5k, then writing a novel is an iron man, for me anyway. You have to let go of the idea that your writing is precious and that you are the ultimate authority, and write with the realization that a lot of what you are writing will not work. At the point you think that you’ve nailed it, you have to be open to sharing what you have with people you trust, so that they can tell you if what you’ve done is really working as well as you think it is. You have to let go of ego and listen honestly, reject the things that don’t fit your vision, and incorporate the comments that you know in your gut makes sense. It takes time to develop that skill. I was lucky in that I had a fantastic support system while writing The Monster’s Daughter. But even through multiple revisions, and edits by my agent, a lot of what I wrote still ended up in the trash during the final editing process because it simply wasn’t contributing to the story. I think that young writers mistakenly think that writing is autonomous. My experience is that it ultimately is a very collaborative effort.

Summar: Besides the history, the geography and physical settings are vivid. You grew up in South Africa, but how did you capture the details of all of these locations so accurately? Are these places you visited while growing up, places you returned to for research, etc.?

Pretorius: Some settings in the novel, like Bloemfontein and Johannesburg, are places that I had lived in growing up. I spent some brief periods of time in Cape Town as well. The major part of the novel, however, is set in Unie, a fictitious town in the Western Cape Province. Friends of mine who had emigrated to the United Kingdom decided to move back to South Africa to live on a farm in that area. I visited them on one of my trips back to South Africa. It was the first time I had ever been in that part of the country. I spent less than three days on the farm, but immediately knew that this was where the novel had to take place. It was beautiful, isolated, and I thought about how a city person (such as myself) would negotiate a shift to life on a farm or in the nearest town, on which Unie was based. I think that this strong sense of place seeded Alet’s character and interactions, and the inciting incident of the novel.

Summar: Throughout the story, it is clear that certain characters, such as Alet, Tessa, and Tessa’s brother Flippie, represent the forces of change and progress, while others, the more villainous antagonists, represent oppression and apartheid. Despite this, each character is illustrated with complexity, with human flaws and weaknesses. How did you balance these characters and avoid presenting them as flat symbols of the messages of the book?

Pretorius: I don’t believe in people being just one thing. Too often we try to make people fit into the one-dimensional view we have of them, or a part we need them to play in the drama of our lives. It’s part of the us/them binary that riddles politics today. It’s easy. It’s dehumanizing. And it doesn’t tell a full story. I grew up in a society that created convenient, shallow narratives to suppress not just non-whites, but women as well. Civil rights movements and feminism have a lot in common in that respect. So I’m not interested in telling a story of binaries. Every so-called “bad” person, has a complex reason for their actions, and every “good” person has dark aspects to their personality that they don’t necessarily show the world. It’s what makes us all human. Alet is a protagonist, but she has many flaws, some of them very unattractive. She does not fit into the box marked hero. On the other hand we have Benjamin, the traditional villain, yet I feel he is one of the most sympathetic characters in the novel, even though others have disagreed with me.

I grew up in a society that created convenient, shallow narratives to suppress not just non-whites, but women as well…So I’m not interested in telling a story of binaries.

TS: Like the characters, you avoid presenting either cause — for instance, that of the Afrikaners and of the ANC, and even askaris, native characters who assisted the Afrikaners — as either all good or all bad. How did you balance these portrayals?

Pretorius: As with people, I think that we need to look deeper at causes to really understand events. We live in a very complex world and it is easy to label X as good and Y as bad to help us negotiate our lives. Unfortunately, nothing is that simple. There are reasons the Afrikaners became the bad guys. The ANC, on the other hand, also did things in the name of the struggle which disqualified it as being inherently good. It was important to me to try to present as much of a truth as I could, which meant that I had to show the good and the bad of both sides. Research helped a lot with this. It was hard to dissuade myself of the human instinct to pick sides, but I tried to make the history speak for itself, even though it was through fictional means.

Summar: Are there are other novels, or even nonfiction works, that may have inspired you in the writing of The Monster’s Daughter? Do you feel like you are engaging in, or continuing, a literary conversation, or are you, perhaps, starting a new one?

Pretorius: As far as influences are concerned, it’s hard to say. I read everything. I love murder mysteries by authors such as Dennis Lehane and Tana French, but I also enjoy science fiction, especially what is termed “mundane” sci-fi. I like the type of speculative fiction that, if we perhaps knew a bit more, or made scientific advances, could very possibly become a reality. I would love to claim that what I’m doing is unique, but there have been many novels that have blurred the borders of genre. I’m thinking specifically here of Smilla’s Sense of Snow by Peter Hoeg which is a fantastic literary novel that incorporates murder mystery, historical events, a strong female protagonist, and a little bit of science fiction to examine the postcolonial tensions between Denmark and Greenland. Sound familiar? The Monster’s Daughter had already been slated for release by the time I read Hoeg’s novel, so I can’t claim it had an influence on what I was writing, but my point is that authors have been pushing the boundaries of genre expectations for a while now. Through technologies such as the internet and smart phones, borders in all aspects of life are getting malleable, less defined. It is a trend that is becoming more prevalent in literature as well and it is liberating as a writer to not have to think about constraints, but rather to use the best aspects of genre to approach story in a different way.