Interviews

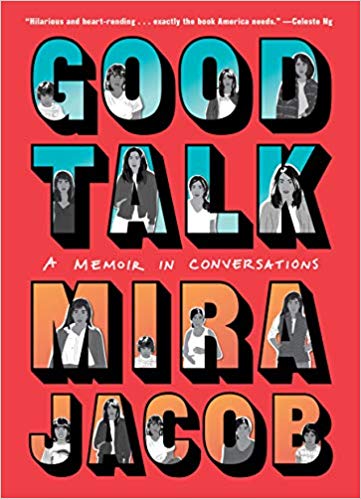

Mira Jacob’s Graphic Memoir “Good Talk” Makes Awkward Conversations Beautiful

The author on surviving difficult interactions about race and politics—and turning them into art

There are many—and I mean many—incidents where I’ve stood agog at comments thrown my way; remained frozen after a backhanded (or full frontal) insult presented like a compliment and considered whether or not I was thinking clearly as I was left to debate what had just happened. These experiences always left me questioning myself: perhaps I was being too sensitive, not thoughtful enough, or, maybe, just maybe, I needed to be more considerate even when I felt myself on the cusp of breaking. When I heard about Mira Jacob’s new book—that it was memoir, that it was graphic memoir, that it was called Good Talk—I knew I’d be drawn to it as a fan of her work. But I didn’t realize how much this book, from start to finish, encapsulated and perfectly illustrated in a unique comic-style the ways in which these encounters had thrown me. I would see and read firsthand that I was not at all alone.

Good Talk: A Memoir in Conversations, Jacob’s second book, isn’t an instructional guide. Rather, it reveals a bevy of experiences for Jacob from childhood to the most recent U.S. presidential election and a bit thereafter. At times direct conversations, divulging how one really feels can feel like a losing battle depending on who we’re engaging with, especially in discord where the divisiveness of politics becomes evident along with the assumptions made about marginalized people by people in passing let alone within actual relationships. None of us are incapable of causing pain and, when we do, do we consider the other party or protect ourselves from these realizations? Good Talk doesn’t shy away from these uncomfortable questions; we’re forced to bear witness to these moments via satire, heart, and introspection. Jacob doesn’t speak for everyone—she speaks for herself—but oh how relatable her individual experience is. I was so glad to talk with Jacob about how this book came together and where the good (and difficult) conversations had may lead us.

Jennifer Baker: You’ve been publishing essays and pieces about your family, about yourself and other people, for years. Do you feel like with Good Talk people are still going to be surprised because they know you through your fiction?

Mira Jacob: I think people are gonna be more surprised by the graphic parts than the memoir parts. Because Good Talk doesn’t function the way the other memoir pieces that I’ve written function, where I feel like I kind of take a subject and really carefully lay it out. It was the opposite with this book. I was working with the opposite impulse, which was to not too carefully lay things out for people, but just to quickly put it down. Get it down and get it drawn and don’t make it into something unspeakably beautiful and refined.

JB: Really?

MJ: It just needed to come out the way it was coming out. And my aesthetic is kind of like a ‘90s zine and I didn’t want to make it prettier. I designed my own font. There are so many different ways to prettify something and I did not want to. And in that same way I didn’t want to have to use the tools of metaphor to say what I wanted to say.

My aesthetic is kind of like a ‘90s zine and I didn’t want to make it prettier.

JB: But there is a structure, because things really do seamlessly weave into this conversation and these emotions through conversations. Which leads us to harder parts of the story, which isn’t exactly linear, the election.

MJ: Exactly. With anything that I do I pay attention to structure, always, and pacing. I think America was surprised when Trump, like really surprised.

JB: Oh yeah!

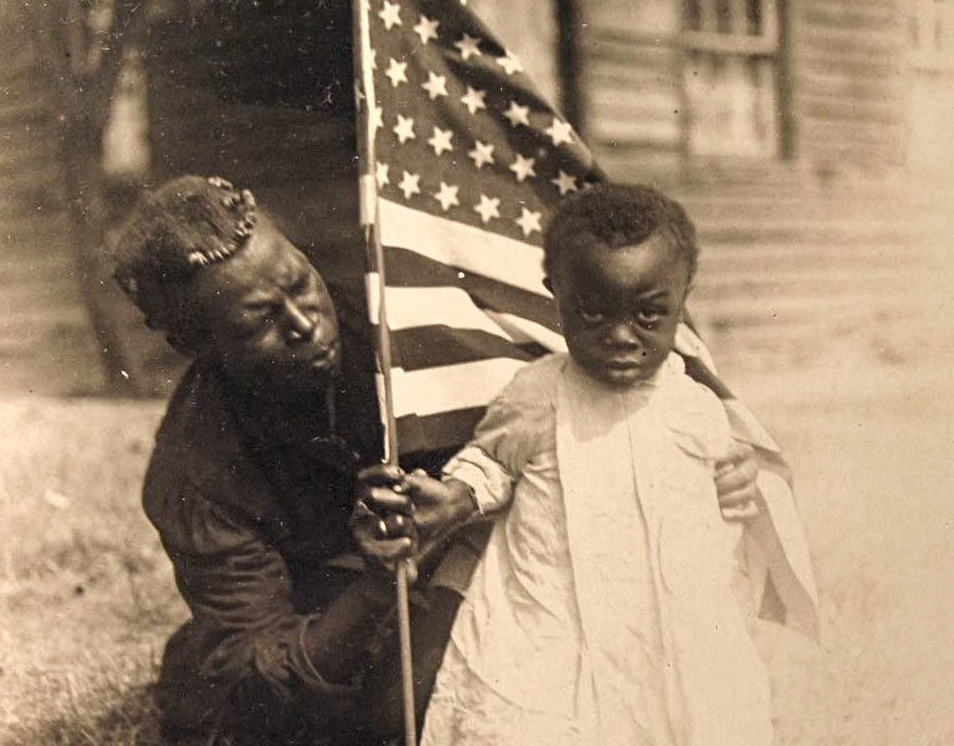

MJ: And I would say, I wish I were one of the super “I wasn’t surprised at all! I knew this was gonna happen.” But I didn’t. I was surprised but not in the way I think in the same way a lot of my White friends were surprised. My surprise was the heartbreak of “Oh this is who we really are.” Their surprise was “This is not who we are!” And it was different. It was a really different way to go through that moment.

JB: We grew up in a “different time.” I mean that in terms of the digital era. I feel like things could be better hidden in terms of the accessibility of it. I was an ‘80s baby so I was very unaware of Reagan and how much his and Nancy’s whole rhetoric of “Say No to Drugs” affected my community and other communities.

MJ: Right.

JB: So the first thought I had was, “Man, this sucks.” But also, “What are the people I know with children going through right now?”

MJ: You know, Tanwi [Nandini Islam] and I talk about it. Because she and Kaitlyn [Greenidge] were both over the night of the election. And then I put [my son] Z to bed. When he went to bed I feel like everybody’s mask just slipped off. I think we were all sort of holding it together for the kid in the room. The minute he was out of the room we were just grief stricken. And falling apart. And I remember sitting on my steps outside. And it was such a sharp contrast, obviously, [with] 2008 and 2012. And I remember saying, “What do we say to him?” And we didn’t have a great answer. We never have great answers at moments like that. Even in hindsight I think to myself, “What would you say now?” What practical advice would you say going forward? And the truth is I really don’t think there is any. My practical advice is: Daddy and I are here. We’re trying to sort through this too. We are wide awake and we’re doing everything we can to help turn the country around. We’re talking to each other. We’re talking to our family.

JB: That concern can look like anxiety definitely comes through here. Especially in text, if we’re talking about formal text. We see a break but it comes off very different. I think we’re meant to kind of hypothesize how the break happens. In Good Talk we’re actually seeing so much of the narrator’s life before/during/after that it makes complete sense these questions being asked.

MJ: It was kind of a good place to channel that. It felt like a good place to kind of put it down and to let it have the space to live. In the moment that it’s happening you have to remember half of our White liberal friends were saying, “This identity politics is really what’s the problem.” In the moment that we’re feeling the anxiety for real things that are happening, our friends are saying “Part of the problem is that you’re feeling the anxiety.” I mean what the fuck is that? How the fuck do you look at someone and say that?

JB: Good Talk spoke to so many things that I know a lot of us are going through. Especially marginalized people. What happens when it’s actually close to home now? Because there’s no finality to this. This is your life and there’s no finality to any of this. Z is still a kid. He loves his grandparents. You love them too; it’s complicated. In art we see it’s complicated, but we still need that ending right? I really appreciate and respect the fact that it was open-ended here.

MJ: I’m glad to hear that. I think that is one of the things that I’ve been sort of anticipating most in this age of “people canceling people” when they crossed a line. Because they need to have a hard stop within themselves. Like, that’s enough. You’ve done enough. I no longer have to interact with you. And I understand and respect that place very much. I don’t have that. I don’t think there are many people that have that choice and go about their days feeling like failures because they’re not taking a moral high ground that isn’t accessible to them in the first place. If I’m gonna say that, I’m going to say “They’re cancelled.” I’m saying to my son, your White family, “Half of you is cancelled.” I would never say that to my child.

JB: This is all very grown up. I’m not used to this. This is all logical, I’m not used to this world.

MJ: Let’s be clear: in the moments of tremendous anxiety I’m not feeling particularly logical, but I do feel like there is a way. And people who have this fantasy of interracial relationships, the fantasy is that if people who are a different race marry it’s because they’ve reached some sort of epic nirvana to which they truly understand each other in a way that reaffirms everything this country is about. And I think the truth is much more complicated. The thing that I hate about the truth getting buried, the truth being that we fight and we don’t understand each other and we have to say things 20 times, both of us, and fight to re-understand each other because we are enormously disappointed by each other and sometimes we’re completely seen by each other.

The problem, when you don’t ever look at the truth of what it is, is that you don’t ever see how it really works and what about that faulty process is very beautiful. And I think that, to me, has been a little bit of a heartbreak from the fallout from the idea that we somehow have to sanitize all of our interracial relations in a way where you’re on the right side or you’re on the wrong side and that’s it.

JB: A lot of what happens in Good Talk is superimposing on those things that people are just making assumption of. The interracial relationships, like you said, and the assumption that you’re “self-hating.” The fact that you are dating various people means you’re “confused.”

MJ: When you actually talk to anyone individually you find out that the monolithic thinking is not really monolithic. Everybody has exceptions. Everybody has weird congealed parts of themselves that do and don’t make sense at different times. But I think for me it just felt very important. Like, I knew when I was writing it, I thought, “Oh there’s gonna be stuff that you write down that you’ll regret later.” I mean not right now. The whole point is my thinking is going to evolve. The whole point is it’s better. And of course, if we’re doing anything right in this world, of course I’m going to look back on something and think “Wow, I sucked on that one.” Of course that’s true, but what does it mean to stand in that moment anyway? What does it means to hold all the complication at once? To know you are not your most evolved self in this moment and you’re gonna write the truth of it.

JB: And one cannot always have an immediate response. I find myself being kind of dumbfounded and that causes paralysis. Realizing “Oh that was horrible.” I don’t see that a lot. It’s witty comebacks. It’s water thrown at your face. But it’s not that kind of paralysis of “Wow, this is something I’m thinking about” and therefore we move into another moment that kind of signifies what is learned or what is felt. I hope that when people read Good Talk it’s causing this kind of self-analysis. With Good Talk I thought, “Oh crap, I’m that type of person. Maybe I need to think about what I’m doing.”

MJ: Obviously I feel like one of the things that this era has pushed us into is this real invulnerability where it’s just considering the hard line of “I’m right and I’m not going to look at this anymore because I know I’m right.” Everybody’s got different moments where that could be the right thing for them, but what I mention I’m looking for is to reach the people that are not in that moment. That are often doing the slower thing and don’t know the immediate thing to say, and don’t have the kind of movie moment under their tongue. And to say I’m right there with you. This is what it looks like.

JB: And you’ve made mistakes?

MJ: Yes, of course. Big ones. I mean, so many. So many.

JB: We all have.

Often there were scenes in the book where I cringed, I cringed reading them.

MJ: Often there were scenes in the book where I cringed, I cringed reading them. You wanna unzip your skin and put it on somebody else and say, “You be me for a little while so I don’t have to feel out what moment was or why I lived it in that particular way.” But I do feel like part of that is to combat what is, I think, one of the things is that I’ve lost, probably like many people, many White friends over the last few years. What it all boils down to is usually due to this simple moment where I try to discuss something but why what they’ve done is hurtful to me and the only discussion they want to have is whether or not they are racist. They don’t even want to have a discussion about it. They want me to tell them they’re not racist. And that’s the only part of the discussion they want to pay attention to. Part of me always just wants to shake them and be like, “Of course you are! Of course I am!” How are we not going to be? In what bubble do you think you grew up where you just somehow escaped— Or what level of thinking do you think you have done that requires you to not think about this anymore and not to question this anymore? Because I feel like there’s this idea they’ve latched onto. They respond to the idea of being woke and this particularly insidious thing where it only happens once. You are woke and then that’s it! And then you are transformed from the frog into the prince. “Now I am the prince, I am no longer the frog.” Don’t you know we’re only ever in the process of waking? It took me a while to figure that out.

JB: As of this conversation, the book isn’t out yet. I don’t know if people felt automatically inclined to make the assumption or project your life into your debut novel whereas now it is your life.

MJ: They definitely did. They did to the point where they thought “I’m so sorry your brother died when you were young.” I said “My brother’s alive. That was a novel. My family is okay. Thank you for asking.” With this I really haven’t had a lot of interaction around it. I’m just sort of geared up for the hell that it will probably be because I think America’s in such a dark place and writing something vulnerable about race is, it’s risky. I think that being a woman, being a brown woman, being a mother—boy, there’s no one people love yelling at more than a mother. I feel like I’ve sort of prepared as well as I can. But what I’m hoping is that on the edges of all of that there will be people that feel seen and heard in ways that are real and matter to them.