essays

My Year in Re-Reading After 40: Sideshow by William Shawcross

Court Merrigan revisits Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia

Author Court Merrigan’s fortieth birthday led him to take the philosopher Seneca’s advice and spend a year re-reading books already in his possession. The books chosen contain some spark of brilliance, howsoever questionable, that have stuck with him throughout the years. The caveats: these are books he’s only read once, that he still owns (no Amazon!), and he can’t read any commentary about them before or after re-reading. How will they measure up? And should they?

BEFORE RE-READING:

No one much cares about Cambodia. Once, a section of its most famous monument was in the backdrop of an Angelina Jolie movie fifteen years ago, and there was that one other movie about fields of killing. But otherwise? Cambodia? What does anyone in America have to say about Cambodia? Nothing.

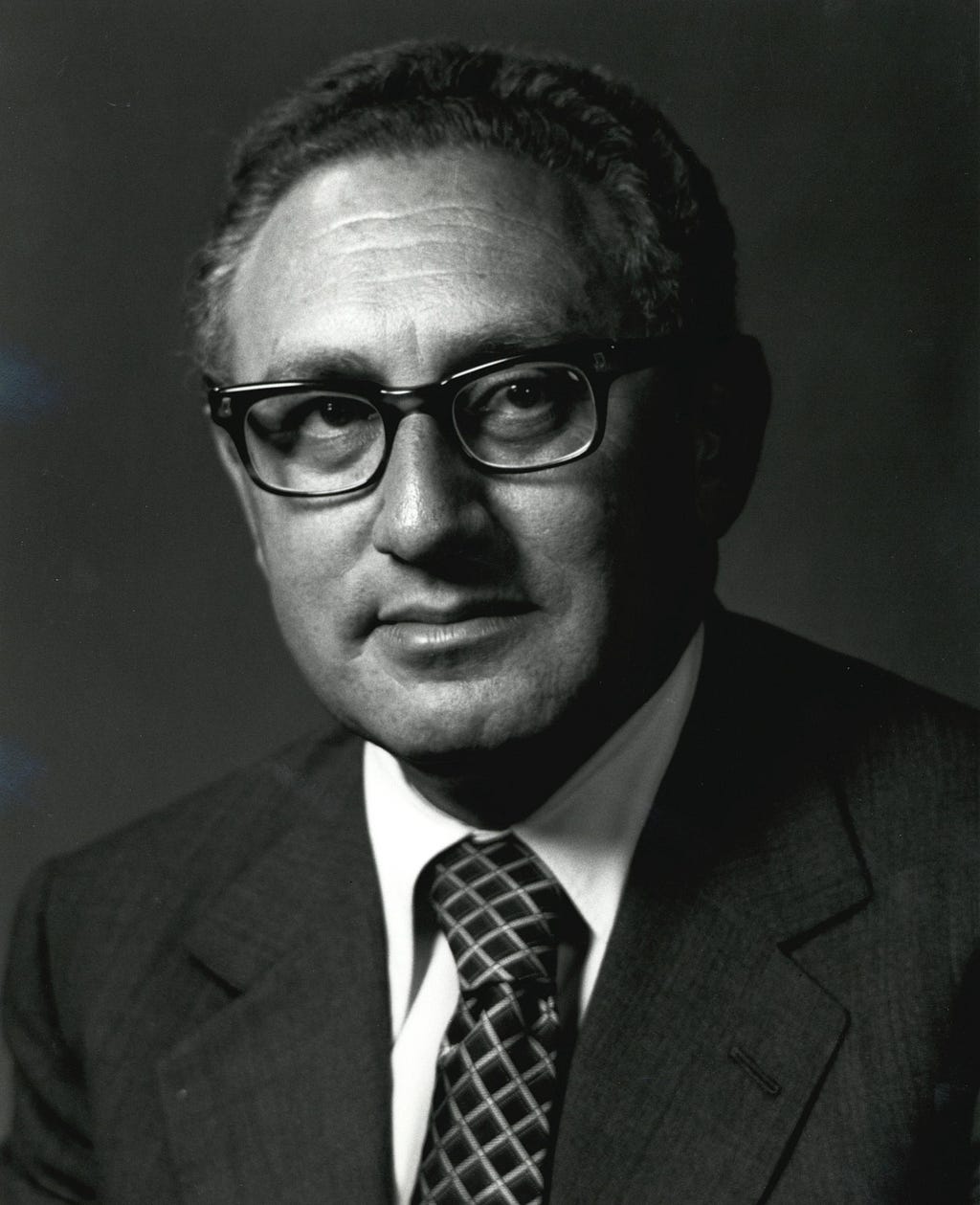

Mission accomplished, Henry Kissinger.

I first visited Cambodia in 1999. The place was something of a free-for-all for Western tourists back then. Piles of ganja littered the guesthouse tables, every moto-taxi driver asked if you wanted a boom-boom girl, a mango shake cost about ten cents, and there were no such things as fences or signs anywhere at Angkor Wat so you could literally climb the stairs to the sanctuary with your bottle of Angkor beer. Just don’t pay too much attention to the amputees in rags begging for change at the entrance: land-minevictims, we were told. We carried on, sweating tourists.

A group of us took the river boat up the Tonle Sap from Phnom Penh to Siem Reap, the city outside Angkor Wat, watching the Cambodian countryside roll past thatched-hut villages and emerald rice paddies awash in tropical heat washing past. Back in Phnom Penh, we rode on the back of hired scooters across the red-dirt countryside, gorged on freshly-butchered chicken in the shadow of a temple that still bore the machine-gunned pockmarks of the Khmer Rouge’s hatred of Buddhism. A bit of real-life foreshadowing for the dark turn the trip was about to take.

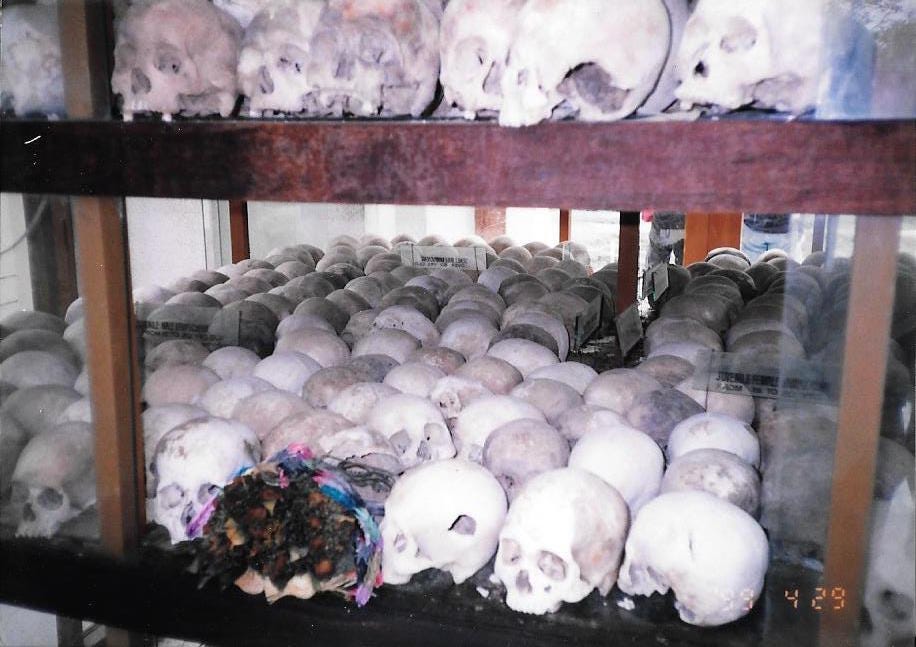

Our scooter drivers took us to a nondescript-looking spot in the midst of the rice paddies a few miles outside Phnom Penh. I didn’t quite understand why we’d been brought there. Until we walked through a rusting gate inside to confront this:

That’s a small portion of the estimated 1.7 million (21% of the population) killed during the Khmer Rouge’s brutal regime. On a percentage basis, the Khmer Rouge genocide dwarfed that of Hitler, Stalin, or Mao. This pagoda of skulls stood as one small monument to the slaughter.

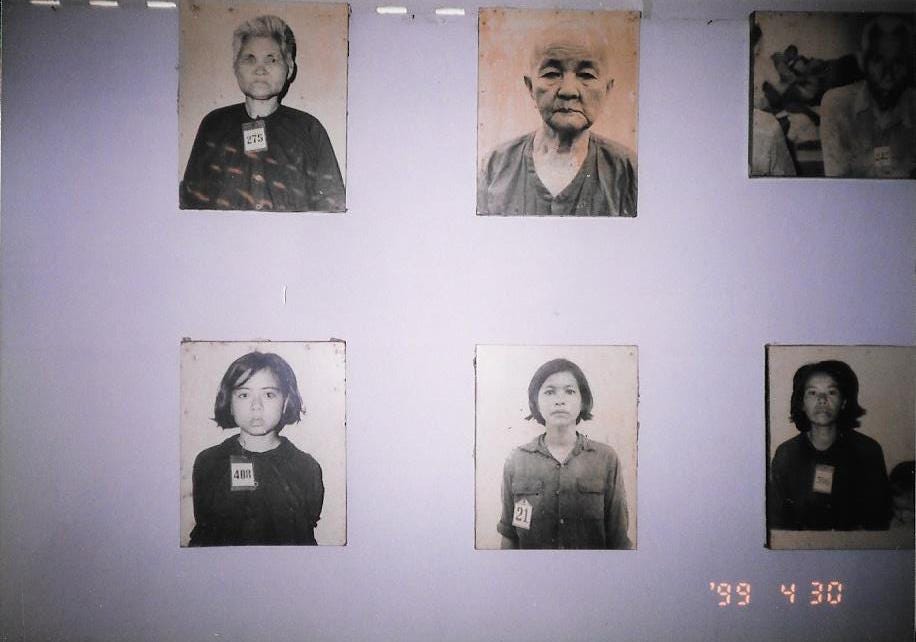

Sobered now, a good deal less the carefree Western tourists ogling Third World exotica from behind the shield of Western passports, our guides then took us to Tuol Sleng prison. Now a museum, this former elementary school served as the Khmer Rouge’s interrogation center where 17,000 men, women and children were tortured and killed.

Which brings me to Sideshow. In those misty, AOL-internet days, you could buy bootlegged books in markets throughout Southeast Asia. I mean actual, physical books, poorly xeroxed on cheap paper and stapled together between a grainy manila cover. I found my original copy of Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon, and the Destruction of Cambodia in one of those market stalls.

I can’t say that this copy of Sideshow was the definitive edition; whole chapters might have been missing. It also leads me to confess that I cheated on my own rules for this series, namely that I only re-read books I have in my actual possession. Somewhere along the line I lost that bootlegged copy. The copy I have now, though it bears the original 1979 copyright, came from Abe Books.

I recall devouring Sideshow in several large and shocking gulps. I had no idea. My God. My country — with the tacit approval of President Nixon and under the guidance of Henry Kissinger — made a very real attempt to bomb Cambodia to the Stone Age. For five years, as I recall, the US Air Force conducted an indiscriminate bombing campaign of the Cambodian countryside in an attempt to disrupt the North Vietnamese Army and the Viet Cong from conducting end-around attacks on South Vietnam. No one knows how many Cambodian civilians in the villages below were killed; hell, the US Air Force didn’t even have maps of the where the villages were.

I knew from history books about our firebombings of German cities in World War II and of course the nukes we dropped on Japan, but that was total war against implacable enemies. Cambodia was a neutral, non-belligerent nation that just happened to be next door to our dirty little war in Vietnam.

As I remember it, in the process of this bombing campaign, we managed to turn the populace against the Cambodian government, itself a US puppet, in favor of the rebel Khmer Rouge communists. When the US withdrew completely from Indochina in 1975, that puppet government collapsed, the Khmer Rouge took over, and four years later, 1.7 million people were dead. Did Henry Kissinger pull the triggers out on the killing fields? No. But he did create the conditions that allowed that genocidal regime to take over, and for that he is little better than a war criminal.

I returned to Cambodia this summer, 8-year old daughter in tow. The ruins of Angkor Wat remain wondrous, though economically speaking the country remains mired decades behind its neighbor to the west, Thailand. Perhaps this has something to do with the fact that the US didn’t secretly drop hundreds of thousands of tons of bombs on Thailand? Henry Kissinger’s legacy lives on in the dirt-poor villages whose inhabitants scrape out a subsistence from red-dirt rice paddies.

But of course it’s not that simple. Cambodia is wracked with endemic corruption, an autocratic government, and the fact that a mere 40 years ago its entire culture was razed to the ground by its own people, the fanatics of the Khmer Rouge. I know it can’t all be Kissinger’s fault. Right?

If there’s one thing I remember about Sideshow, it’s that it provides context. Lots and lots of context. It names the names, it gets the dates right, it has the maps. Trouble is, I don’t recall the specifics of that context. I think our memories of books like Sideshow — provocative, laying claim to truth — are important to re-evaluate. After all, years later, the details are forgotten. As with any book, what you take with you is the general impression. But over a course of years the details of the book transform into personal touchstones. Oversimplified, devoid of context.

For me, from Sideshow, I took the idea that Henry Kissinger is a war criminal, and that our dirty little war wrecked a once-beautiful and peaceful country. I wonder if these personal memes will stand up to a re-read. You shouldn’t go accusing someone of war crimes unless you’re awful sure those charges could stick.

AFTER READING:

If Sideshow is accurate — and given the exhaustive range of its research, there’s no reason to suppose it’s not — then that little touchstone I’ve been toting around all these years about Henry Kissinger being a war criminal is correct. Under the pretense of breaking up North Vietnamese supply lines, President Nixon authorized — and Henry Kissinger orchestrated — a massive secret bombing campaign of Cambodia, lying to Congress, the Pentagon, and the American people along the way.

The bombing campaign culminated in a short-lived and doomed ground invasion of Cambodia itself in the early summer of 1970. Unnumbered Cambodian civilians were killed (no attempt was made to keep a tally) along with some Communists, American troops, and South Vietnamese soldiers. All these efforts failed as spectacularly as similar efforts in Vietnam. The Viet Cong and other Vietnamese troops simply retreated further into Cambodia, destabilizing that country, alienating the populace, and clearing the way for murderous Khmer Rouge cadres to emerge from the jungle when, inevitably, American troops retreated.

When Shawcross asked the deposed King of Cambodia, Sihanouk, about the lessons of recent history, the king said:

There are only two men responsible for the tragedy in Cambodia, Mr. Nixon and Dr. Kissinger. Lon Nol [Cambodian President, 1970–75] was nothing without them and the Khmer Rouge were nothing without Lon Nol. Mr. Nixon and Dr. Kissinger gave the Khmer Rouge involuntary aid because the people had to support the Communist patriots against Lon Nol. By expanding the war into Cambodia, Nixon and Kissinger killed a lot of Americans and many other people, they spent enormous sums of money — $4 billion ($17.8 billion in 2015 dollars) — and the results were the opposite of what they wanted. They demoralized America, they lost all of Indochina to the Communists, and they created the Khmer Rouge.

The king is himself deeply complicit in that tragedy — he allied himself with the Khmer Rouge in hopes of getting his throne back. Indeed, there is plenty of blame to go around. The puppet regime of Lon Nol was deeply corrupt and hopelessly incompetent at defending its own people; the Chinese shipped arms to the Khmer Rouge, as did the North Vietnamese; the Soviet Union supported chaos in Cambodia as an anti-American policy; the Khmer Rouge themselves were murderous ideologues. But the King is right: it all goes back to those two men, Kissinger and Nixon.

Nixon’s personality and history is, of course, well-known. Kissinger, once world-famous, occasionally surfaces from retirement for occasional op-eds and to be criticized by hopeless presidential candidates. These days, however, Kissinger is no longer a household name. Lucky for him, all things considered.

Most generously, you might consider Kissinger an intellectual “freak” and thus, in true intellectual fashion, incapable of understanding the actual world as it actually is, which led to his bloody blunders in Cambodia and elsewhere. Blunders such as:

The pilots of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing actually complained that their maps “lacked sufficient detail and currency to pinpoint suspected enemy locations with some degree of confidence.” … [An embassy official] cut out, to scale, the “box” made by a B-52 strike and placed it on his own map. He found that virtually nowhere in central Cambodia could it be placed without “boxing” a village. “I began to get reports of wholesale carnage,” he says. “One night amass of peasants from a village near Saang went out on a funeral procession. They walked straight into a ‘box.’ Hundreds were slaughtered.”

More likely, it seems to me, Kissinger’s enormous ego and Trump-like penchant for self-aggrandizing rendered him indifferent to the consequences of his policies:

When asked about the exacting way he treated State Department officials, Kissinger once replied, “Why, Thomas Jefferson was a fine Secretary of State, and he had slaves.”

I, however, am prone to a more emotional response. This happens when you’ve gazed on a pagoda of skulls, sweltering under a washed-out tropical sky, or upon a bed frame where children considered enemies of the state were tortured to death. I do not think there is or ought to be forgiveness for the men who carried out such atrocities, no matter how strongly they believed in the pure truth of their creeds. Ought there be forgiveness for the man who created the conditions under which such atrocities were carried out from an office in the distant capital of a far-off superpower?

Perhaps you are kinder than I am. Perhaps you think so. I’m not. I can’t.

Sideshow showcases the American political and military establishment at its nihilistic worst; lives destroyed, treasure wasted — and for what? What did we gain in Cambodia? What did anyone gain in Cambodia? Save a few years of blood-soaked power for the Khmer Rouge leadership — nothing. No one gained a goddamn thing.

And certainly the American establishment appears to have learned very little (nothing?) from the lessons of Cambodia. We’re still engaging in endless war (see: Terror, the Global War on) and the executive branch continues to flout the Constitution with its virtually unchecked power (see: Obama’s drones, Bush’s Guantanamo and black sites, Clinton’s cruise missiles). Meanwhile small countries and their people continue to suffer from the aggression of fanatics, powered by American weaponry and under conditions created by American geopolitical maneuvering (see: Afghanistan).

But it’s not the geopolitical fallout that got me most about Sideshow. For the most part, Shawcross stays laser-focused on the policies and the big figures. But sometimes he breaks from the political to the personal, and this the book at its most heartbreaking. Here he is on Khmer Rouge foot soldiers:

That summer’s war provides a lasting image of peasant boys and girls, clad in black, moving slowly through the mud, half-crazed with terror, as fighter bombers tore down at them by day, and night after night whole seas of 750-pound bombs smashed all around. Week after week they edged forward, forever digging in, forever clambering slippery road banks to assault government outposts, forever losing comrades and going on in thinner ranks through a landscape that would have seemed lunar had it not been under water.

Even amid the carnage and the corruption, there are moments of great courage and grace. Here is high government official and royal prince Sirik Matak refusing the American ambassador’s offer to join the airlift out of Phnom Penh as the Khmer Rouge closed in to conquer the city:

Dear Excellency and friend. I thank you very sincerely for your letter and for your offer to transport me towards freedom. I cannot, alas, leave in such a cowardly fashion.

As for you and in particular for your great country, I never believed for a moment that you would have this sentiment of abandoning a people which has chosen liberty. You have refused us your protection and we can do nothing about it. You leave and it is my wish that you and your country will find happiness under the sky.

But mark it well that, if I shall die here on the spot and in my country that I love, it is too bad because we all are born and must die one day, I have only committed this mistake of believing in you, the Americans.

Please accept, Excellency, my dear friend, my faithful and friendly sentiments. Sirik Matak.

America did abandon Cambodia. The prince was later executed by the Khmer Rouge.

And yet, for all the death and destruction, Sideshow throws out rays of hope in spite of itself. When the book was published in 1979, it must have very much seemed like Cambodia was destroyed. It was not.

I can report that thankfully, and despite Henry Kissinger’s best efforts, Cambodia still stands. The slice of Cambodia we saw this summer is booming. Thriving, even. Millions of tourists visit Angkor Wat every year and there are shiny buildings everywhere. True, it’s no paradise. There is still a great deal of grinding poverty, and the political system is rife with corruption and violence. While my daughter and I supped at a restaurant in Siem Reap with waiters and cooks and tour guides at our beck and call, we saw saw street kids , no older than her, huffing gasoline out of plastic sacks and begging for money at the tables. We spent some time talking about what a wonderful job she did choosing her parents.

We also met a remarkable man. Stephane de Greef, aka the Bug Man, has spent 13 years in Cambodia. A forest engineer from Belgium, he originally came to Cambodia to assist in de-mining efforts (another legacy of the Khmer Rouge). He’s also a cartographer, and has been heavily involved in efforts to map newly-discovered sections of the ancient city of Angkor. But de Greef’s true passion is insects. As is my daughter’s — the two were simpatico from the first minute they met.

In the Cambodian forest de Greef has discovered insect species wholly new to science, and documented dozens and dozens more. That is, when he’s not busy flying drones over that same forest, chasing down new ruins. The Guardian rates him as one of the Top 10 tour guides in the world, and I can report from the day my daughter and I spent with him, he lives up to the billing. He is a walking treasure house of knowledge on Cambodian flora, fauna, history and culture.

I mention de Greef because it’s pretty remarkable that a country that not 40 years ago was being ravaged by genocidal ideologues can now host a scientist, who in turn can lead an 8-year old into the forest to explore for insects utterly without fear. I’d like to think someday my daughter will be able to take children of her own into the mountains of Afghanistan. And more to the point, that the Afghan people, like the Khmer people before them, will be prospering despite the ravages of the past.

I suppose such a view is hopelessly starry-eyed and naïve, and perhaps tinged with neo-colonialism (“I want these exotic places to be pretty and neat so my kids can visit!”). I’ll own both of those critiques; I do want the wonderful places of the world to be peaceful and prosperous enough for my children’s children to visit. And ultimately, I do have faith in humanity’s ability to weather the worst of what we can do to ourselves.

The alternative, it seems to me, is to let the Henry Kissingers of the world rule the world, spouting grandiose plans and raining down bombs. I decline to let such men go unchallenged. I choose to believe in a better world that can emerge from the wreckage they create.

DOG-EAR REPORT:

Kissinger on his role in Cambodia:

“I may have a lack of imagination, but I fail to see the moral issue involved.”

Yes, Henry. You lack imagination. And a good deal more.

Sound familiar?

The invasion not only was disastrous for Cambodia, but it also had serious long-term effects on Vietnamization and on the nature of the Nixon administration itself. The way in which it was conducted broke rules of good policymaking, ignored vital intelligence, and disregarded political realities. Congress, to whom the Constitution assigns the power to declare war, was totally ignored. So was almost everyone else.

Republican Congressman Pete McCloskey after a tour of Cambodia shortly before it fell to the Khmer Rouge:

I can only tell you my emotional reaction, getting into that country. If I could have found the military or State Department leader who has been the architect of this policy, my instinct would be to string him up. Why they are there and what they have done to the country is greater evil than we have done to any other country in the world, and wholly without reason.

Next: A retreat to the pastoral.