interviews

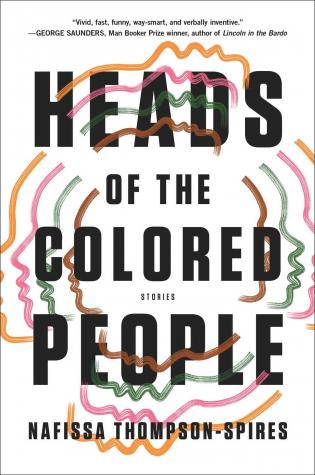

Nafissa Thompson-Spires Is Taking Black Literature in a Whole New Direction

If you’re ready to move on from the expected narratives, her debut collection is the book you’ve been waiting for

Many Black writers remain tethered to retelling what feels like the same tale, one that overtly centers racial injustice and relies on the past instead of looking out toward the future. So, when Kiese Laymon tweeted, “Nafissa Thompson-Spires wrote what we been waiting for in Heads of the Colored People. Goodness gracious,” I knew exactly what he meant.

Heads of the Colored People, Nafissa Thompson-Spires debut collection of short fiction sketches (think along the lines of vignettes but longer), is a new narrative in the canon of Black literature, one rooted in the lives we lead right now. From bickering bougie Black mothers passing notes to one another inside their kids’ backpacks to a young girl contemplating how to best notify her Facebook friends of her impending suicide, Thompson-Spires’ collection overtly fights against the belief that Black literature has to reflect a certain narrative of racial oppression and suffering. Heads of the Colored People is a forward-looking mosaic portraying the unique lives of modern Black characters.

Thompson-Spires earned a Ph.D. in English from Vanderbilt University and a Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing from the University of Illinois. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The White Review, Los Angeles Review of Books Quarterly, StoryQuarterly, Lunch Ticket, The Feminist Wire, and elsewhere. Heads of the Colored People publishes in April with Simon and Schuster’s Atria/37 Ink imprints.

I got to know Thompson-Spires when we both attended the Tin House Summer Workshop this past June. We chatted on the phone about this new nexus of Black identity, how her book introduces a unique way of examining race in fiction, and 1980s Canadian television.

Tyrese L. Coleman: I agree with Kiese that your book is what we have been waiting for, especially Black Gen Xers, Millennials, and Xennials. The stories aren’t dependent on race, but feel incidental to it. I see how race informs the lives of your characters, but does not define them.

Nafissa Thompson-Spires: In some ways, I agree with you completely and in other ways I’m not sure. I feel like the book is hyper-racial, but maybe hyper-racial in a surprising way. All the stories are really about race, or at least they could be interpreted that way. But, I think, first and foremost, they’re about these unique characters. So, maybe they’re about race in ways we just haven’t seen before — about intersections between upper-middle class identity and race, or disability and chronic illness and race. But the racial part is important.

One of the things I was trying hard to do is write about contemporary Black people. It’s important for us to be looking back because that history undergirds all the problems we’re having now, and always will. But it’s equally important for us to see stories about Black people today. I wanted to write about Black people today, at least from the ‘90s to the present, and the kind of unique struggles they deal with. Because we are one of the first generations post-integration living out everyday problems.

It’s important for us to be looking back. But it’s equally important for us to see stories about Black people today.

TLC: Your characters are a natural progression or the children of the people Margo Jefferson wrote about in Negroland. I related to some of the stories on a personal level. The characters are my age, I knew the references, and their outlook on life. And some of the stories, I couldn’t relate to because I didn’t come from a middle-class upbringing…or the West Coast. It reminded me of Paul Beatty and the very Los Angeles feel of The Sellout.

NTS: I like that you said you identified with some of it, and did not identify with other parts of it because I really appreciate that honesty.

When I was young, it seemed like whenever I read a Black book, it was almost always about some deep, tragic suffering, like people were having crosses burned on their lawn, and they were usually working-class families. I didn’t see anything about a Black girl who was stuck in a white school, which is what I was dealing with, and how to deal with being different at that level, and on being middle class or upper-middle class and not really fitting in anywhere. Now there are lots of those books, but there weren’t for me as a kid.

In some ways, I was just trying to write the stories I felt like I hadn’t seen and the characters I felt like I wanted to see more of when I was younger. Definitely, people like Paul Beatty and Colson Whitehead have represented those kind of families and individuals in recent years. Even though different contexts, Chimimanda [Ngozi Adichie] and ZZ Packer have done a little more with middle-class Black characters. But, I still felt like there were specific kinds of characters, characters who were really weird and nerdy, that I hadn’t quite seen.

When I was young, it seemed like whenever I read a Black book, it was almost always about some deep, tragic suffering.

TLC: I feel like these are the type of individuals that exist and are part of who we are that people don’t associate with Black culture. My favorite piece is the very first set of vignettes that the book gets its title from. Everyone has their own personal outlook. They are joined by their blackness but how they respond to their blackness is totally different.

NTS: All the stories in some way are trying to deal with the pressure of respectability, and the characters are either working with respectability or against it. So, somebody like Fatima in “Fatima, the Biloquist: A Transformation Story” is really burdened by her image, and so is Randolph in “The Necessary Changes Have Been Made.” They’re both hyper-aware of how people perceive them and worried about fitting in with White people and looking a certain way. Someone like Riley has all these interests in common with white people but is doing his own thing no matter what they think, and so does his girlfriend Paris in “Heads of the Colored People.” In some ways, I think the collection is trying to deal with the pressures of all that baggage, which I think we inherited from the generation before us, and to think about new ways of trying to be Black in spite of that pressure.

But I think these people have always existed. There’s always been this huge spectrum of Black people but we don’t tend to read about the ones who are marginalized within a marginalized group. Growing up, my immediate family were the only people who were upper middle class in my extended family. The rest of the family would call us the “bougie” ones or make fun of us for being like the Huxtables. It was always derogatory because they weren’t living that way. Even though we were already Black, we were perceived as the “wrong” Black. We all know that person who gets made fun of for not being “Black enough” or for hanging out with white people too much, and I wanted to talk about what it feels like to be in that situation. But also, to be in that situation and navigate it, not just to suffer.

We all know that person who gets made fun of for not being “Black enough” or for hanging out with white people too much, and I wanted to talk about what it feels like to be in that situation.

TLC: Why sketches? The stories aren’t traditional narratives with a beginning, middle and end.

NTS: I started thinking about a theme. The theme was “The Heads of the Colored People,” which is a collection of literary sketches by James McCune Smith, a Black abolitionist writer who used the sketch form to write about citizenship. Initially, I was trying to hold on to this framework…make my book in conversation with his. But it was too much of a constraint. So, I decided to tell the stories I wanted to tell and keep the title and think about heads more broadly, in terms of leadership, psychology, and literary, physical heads in the form of a concussion story. But the titular story and overarching theme came from trying to write back to James McCune Smith’s work. I would like to think of these as full stories that begin and end in medias res.

TLC: That’s interesting. The ending in medias res made me think these people were going to continue on…as if we dropped in on them in the middle of turmoil.

NTS: I’m obsessed with two things: the ‘80s and Canadian TV, and especially ‘80s Canadian TV. And Canadian TV has this thing where the kids always end in peril. There is never a nice tidy ending. It’s “I’m bawling my eyes out,” then credits. Maybe that aesthetic has influenced my writing in some unconscious way.

TLC: With such a forward-facing collection, what are you hoping to see for the future of Black literature?

NTS: I’m really proud of all the people who are writing. I love Kiese’s work. Long Division is one of the best novels I’ve ever read. I like Mat Johnson’s work. I like what I am starting to read of Jesmyn Ward’s work. I like that there’s a lot more variety now. I just read Stay With Me by Ayobami Adebayo and it’s one of my favorite books that I’ve read this year. I like that there’s variety and there is space for what everyone is doing.

I think what I want is not so much from Black writers themselves, but from the literary gatekeepers. I want them to recognize us all and not pit us against each other. There can’t only be this narrative of the one “anointed Black writer” who gets the attention at a time. People can get equal attention and an equal playing field. I also want them to recognize that Black writing is art in the same way other writing is. That we can take risks that other writers can take. I would like to see more space for all of us and more recognition of the many things we can be, which is what my collection is about.